Conflict of Laws W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SEC News Digest, 07-14-1982

tI.S. SEetlRITIEG I.N9 COMMISSION ANItOUNCEIENTS EXCHANGE COMMISSION SEC GOVERNMENT BUSINESS FORUM ON SMALL BUSINESS CAPITAL FORMATION The. Securities and Exchange Commission is planning the first SEC Government Business Forum on Small Business Capital Formation in an attempt to establish a dialogue on the capital formation problems besetting the small business community. This program will provide a forum for small businesses, government regulatory agencies, and private sector organizations concerned with small business issues to discuss the existing impediments to small business capital formation particularly in the areas of taxa- tion, securities and credit. The Forum is scheduled to be held September 23-25, 1982, in Washington, D.C. The format of the Forum provides that participants will meet in working discussion groups of 15-20 persons to cover eight major issues with the intent of developing specific recommendations. In order to achieve these objectives, the size of the Forum must be limited. Each participant must be generally familiar with all the dis- cussion papers being prepared for distribution prior to the Forum. Further, each participant will be requested to act as a discussion leader on one major issue. Members of the public interested in being considered for active participation at the Forum should promptly complete and return the biographical sheet available from the Office of Small Business Policy, Division of Corporation Finance, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, 500 North Capitol Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20549 by August 2, 1982. The biographical sheet will facilitate the selection of small busi- nesspersons, lawyers, accountants and others who are knowledgeable in small business issues and who could make the most meaningful contribution to the Forum. -

Squeezing Silver Peru's Trial Against Nelson Bunker Hunt

Job Name: -- /407397t Squeezing Silver In order to view this proof accurately, the Overprint Preview Option must be set to Always in Acrobat Professional or Adobe Reader. Please contact your Customer Service Representative if you have questions about finding this option. Job Name: -- /407397t A true story Minpeco S.A. v. Hunt (New York, February–August 1988) In order to view this proof accurately, the Overprint Preview Option must be set to Always in Acrobat Professional or Adobe Reader. Please contact your Customer Service Representative if you have questions about finding this option. Job Name: -- /407397t Squeezing Silver Peru’s Trial Against Nelson Bunker Hunt by Mark A. Cymrot In order to view this proof accurately, the Overprint Preview Option must be set to Always in Acrobat Professional or Adobe Reader. Please contact your Customer Service Representative if you have questions about finding this option. Job Name: -- /407397t www .twelvetablespress .com P.O. Box 568 Northport, New York 11768 © 2018 by Twelve Tables Press All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Name: Mark A. Cymrot Title: Squeezing Silver Description: Northport, New York: Twelve Tables Press, 2018 ISBN: 978-1-946074-19-5 Subjects: Law—United States/Law, LC record available at https:lccn .loc .gov / Twelve Tables Press, LLC P.O. Box 568 Northport, New York 11768 Telephone (631) 241-1148 Fax: (631) 754-1913 www .twelvetablespress .com Printed in the United States of America Cover Art: Rebekah Feldman In order to view this proof accurately, the Overprint Preview Option must be set to Always in Acrobat Professional or Adobe Reader. -

In the United States District Court for the Northern District of Texas Dallas Division Nelson Bunker Hunt, William § Herbert Hu

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS DALLAS DIVISION NELSON BUNKER HUNT, WILLIAM § HERBERT HUNT, HOUSTON B. HUNT § LAMAR HUNT, ALBERT D. § HUDDLESTON, and DOUGLAS H. § HUNT, § § Plaintiffs, § § CA 3-81-0316-F v. § § UNITED STATES SECURITIES § AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION, § § Defendant. § AMENDED VERIFIED COMPLAINT FOR INJUNCTIVE RELIEF Plaintiffs Nelson Bunker Hunt (“N. B. Hunt”), William Herbert Hunt (“W. H. Hunt”), Houston B. Hunt, Lamar Hunt, Albert D. Huddleston and Douglas H. Hunt (hereinafter “plaintiffs”), for their amended complaint1 for injunctive relief against Defendant United States Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”), allege as follows: JURISDICTION AND VENUE 1. Plaintiffs are all citizens of the United States and reside in Dallas, Texas. 2. The SEC is an agency of the United States. 3. Plaintiffs’ claim for relief arises under the Fourth and Fifth Amendments to the United States Constitution, and further arises under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, 15 1 The number of each paragraph (or portions thereof) in this Amended Verified Complaint which were not included in plaintiffs’ original verified complaint or which have been modified have been placed in brackets for ease of identification. U.S.C. §§78a-78hh-1 (the “1934 Act”), the Right to Financial Privacy Act of 1978 (the “RFPA”), 12 U.S.C. §§3401-3422, and The Commodity Futures Trading Commission Act of 1974 (the “CFTC Act”), Pub. L. No. 93-468, 88 Stat. 1389 (codified in scattered sections of Titles 5 and 7 of the U.S. Code). 4. This Court has jurisdiction over the subject matter of this action by reason of 28 U.S.C. -

The Rearguard of Freedom: the John Birch Society and the Development

The Rearguard of Freedom: The John Birch Society and the Development of Modern Conservatism in the United States, 1958-1968 by Bart Verhoeven, MA (English, American Studies), BA (English and Italian Languages) Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Faculty of Arts July 2015 Abstract This thesis aims to investigate the role of the anti-communist John Birch Society within the greater American conservative field. More specifically, it focuses on the period from the Society's inception in 1958 to the beginning of its relative decline in significance, which can be situated after the first election of Richard M. Nixon as president in 1968. The main focus of the thesis lies on challenging more traditional classifications of the JBS as an extremist outcast divorced from the American political mainstream, and argues that through their innovative organizational methods, national presence, and capacity to link up a variety of domestic and international affairs to an overarching conspiratorial narrative, the Birchers were able to tap into a new and powerful force of largely white suburban conservatives and contribute significantly to the growth and development of the post-war New Right. For this purpose, the research interrogates the established scholarship and draws upon key primary source material, including official publications, internal communications and the private correspondence of founder and chairman Robert Welch as well as other prominent members. Acknowledgments The process of writing a PhD dissertation seems none too dissimilar from a loving marriage. It is a continuous and emotionally taxing struggle that leaves the individual's ego in constant peril, subjugates mind and soul to an incessant interplay between intense passion and grinding routine, and in most cases should not drag on for over four years. -

Manipulation of Commodity Futures Prices-The Unprosecutable Crime

Manipulation of Commodity Futures Prices-The Unprosecutable Crime Jerry W. Markhamt The commodity futures market has been beset by large-scale market manipulations since its beginning. This article chronicles these manipulations to show that they threaten the economy and to demonstrate that all attempts to stop these manipulations have failed. Many commentators suggest that a redefinition of "manipulation" is the solution. Markham argues that enforcement of a redefined notion of manipulation would be inefficient and costly, and would ultimately be no more successful than earlierefforts. Instead, Markham arguesfor a more active Commodity Futures Trading Commission empowered not only to prohibit certain activities which, broadly construed, constitute manipulation, but also to adopt affirmative regulations which will help maintain a 'fair and orderly market." This more powerful Commission would require more resources than the current CFTC, but Markham argues that the additionalcost would be more than offset by the increasedefficiencies of reduced market manipulation. Introduction ......................................... 282 I. Historical Manipulation in the Commodity Futures Markets ..... 285 A. The Growth of Commodity Futures Trading and Its Role ..... 285 B. Early Manipulations .............................. 288 C. The FTC Study Reviews the Issue of Manipulation ......... 292 D. Early Legislation Fails to Prevent Manipulations .......... 298 II. The Commodity Exchange Act Proves to Be Ineffective in Dealing with M anipulation .................................. 313 A. The Commodity Exchange Authority Unsuccessfully Struggles with M anipulation ................................ 313 B. The 1968 Amendments Seek to Address the Manipulation Issue. 323 C. The 1968 Amendments Prove to be Ineffective ............ 328 tPartner, Rogers & Wells, Washington, D.C.; Adjunct Professor, Georgetown University Law Center; B.S. 1969, Western Kentucky University; J.D. -

From Cornering to Cornered: the Hunt Brothers Adventure in the Silver Market Author: Tanya Smith

FROM CORNERING TO CORNERED: THE HUNT BROTHERS’ ADVENTURES IN THE SILVER MARKET Introduction What can we learn from a case from the 1970s? The story of the Hunt Brothers’ spectacular rise and fall is timeless. This “throwback” case helps us to understand the rationale behind the rules governing the commodities markets today. It also raises questions about the ethics or legitimacy of changing the rules “in the middle of the game.” Introduction Mark Cymrot was sitting in his office at the Justice Department (“DOJ”) when he heard the phone ring. After nine years at the DOJ, Mark had earned the role of Special Litigation Counsel. In essence, he was “the [government’s] lead lawyer on important cases.” He picked up and heard the voice of Ted Sonde, former deputy chief of enforcement at the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”). Ted began the call by providing Mark with a little context. A boutique law firm, Cole Corette & Abrutyn, had hired Ted to assist them in their representation of Minepco, a Peruvian mining company. Minepco had lost over $80 million after the price of silver surged 500% from the summer of 1979 to the winter of 1980.1 See Exhibit 1: Silver Prices. The mining company wanted to sue the Hunt brothers (who, along with their acquaintances, had acquired control of over 250 million ounces of silver during this period)2 for market manipulation. Ted explained that while he had agreed to “file the complaint and fight the early skirmishes, he did not want to focus his entire practice on a single case.” Thus, he wanted to know if Mark might consider leaving his job at the DOJ. -

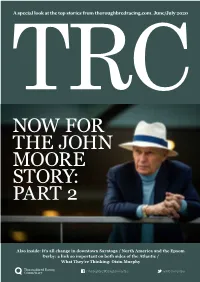

Now for the John Moore Story: Part 2

A special look at the top stories from thoroughbredracing.com. June/July 2020 NOW FOR THE JOHN MOORE STORY: PART 2 Also inside: It’s all change in downtown Saratoga / North America and the Epsom Derby: a link so important on both sides of the Atlantic / What They’re Thinking: Oisin Murphy /ThoroughbredRacingCommentary @TRCommentary Two of the most exciting young sires in the world. From Royal Ascot winners come Royal Ascot winners Frankly Darling | by Frankel Palace Pier | by Kingman Ribblesdale Stakes Gr.2, Royal Ascot St James’s Palace Stakes Gr.1, Royal Ascot Bred by Hascombe & Valiant Stud Ltd Bred by Highclere Stud And Floors Farming +44 (0)1638 731115 [email protected] ® www.juddmonte.com What’s top of John Moore’s bucket list as he bids farewell to ‘Disneyland’? JA McGrath | July 15, 2020 John Moore is packing up and leaving Hong Kong at the end of a spectacular career, in which he sent out 1,734 winners of prize money totalling US$270 million, making him the most successful trainer since racing turned professional there in 1971. John Moore: Stepping down after 35 years as a trainer in Hong Kong, having trained the winners of six Hong Kong Derbys and being responsible for eight Horses of the Year. Photo: HKJC But Moore, 70, is not retiring. Far from Moore is very attached to everything John Moore with his brother Gary and father it. The Australian-born son of the Hong Kong, which is perfectly George: After today, the Moore family name will not be represented in Hong Kong racing for the first legendary George Moore is looking understandable for one who has spent time in 49 years. -

10 Silver Squelchers & Their Interesting Associates

#10 Silver Squelchers & Their Interesting Associates Presented January 2015 by Charles Savoie 1980 Pilgrims Society rosters---Hunt-Arab Silver Play Crushed! Three second message from The Pilgrims Society click here before progressing. ********************* http://www.nosilvernationalization.org/ “Uncounted millions are spent to prevent the miner from getting an honest price for his production.” ---The Mining Record (Denver), July 11, 1946 “The new law made it “a felony for any person to manipulate or attempt to manipulate the price of any commodity in the futures market.” ---Page 112, “Beyond Greed---The Hunt Family’s Bold Attempt to Corner the Silver Market” (1982) The unstated definition of price manipulation in silver is that it can only transpire on the long side. Try passing an economics course in a university if you mention shortside silver price meddling. That may even apply in Idaho and Nevada scholastic institutions. I’ve seen faculty get red faced with hysteria! The author worked first for Lord Astor (Pilgrims London) then for Lord Thomson of Fleet (Pilgrims London) --- Astor was directly descended from John Jacob Astor who as a director of the second United States Bank (1816-1836) was a silver suppressor! Page 71 has this---“In 1976 the Hunts attracted the attention of the CFTC, which was concerned at the concentration of so much silver in so few hands.” Again---concentration in silver is an issue for regulators only if on the long side! The gold and silver shorts created the CFTC to cover for them! Page 221 has this, referring to a banker in Chicago--- “The United States government was not willing to let free market forces operate in the banking system.” The destruction of the Hunt-Arab silver play was a warning to the new rich in the USA and the world to not go long silver! Not only the Hunts, but regiments of small investors were burned in yet another Pilgrims Society monetary inferno. -

HUNT (9 Et 19 Janvier 1988) À Keeneland

DISPERSAL NELSON BUNKER HUNT (9 et 19 janvier 1988) à Keeneland pleine de 283 KINK M 1984 Naskra A Twinkling Alphabatim 588 WATERBUCK M 1974 The Axe II Abyssinia Dahar 445 SANDATE M 1984 Majestic Light Accommodate Vaguely Noble 4 ICEOPAK C 1987 Isopach Adieu 3 SHERIFA F 1986 Lear fan Adieu 96 CHARMING ALIBI M 1963 Honeys Alibi Adorada non saillie 6 AMALFITANA F 1987 Liloy Alerted (FR) 7 ARC'S PROSPECT F 1986 Youth Alerted (FR) 94 CHANGE PLACES M 1978 Gallant Man Alice Sit Down 8 MAID AT ARMS F 1987 I'm Glad (ARG) Allee's Princess 296 LAKE OF THE ISLES M 1972 In Reality Allert Miss Arctic Tern 484 SMILING SUN M 1979 Smiling Jack Alohajet Liloy 11 EXCELL A LOT F 1987 Exceller Alota Calories 10 BONARIO C 1986 Riverman Alota Calories 403 QUADRUPLER M 1976 Vaguely Noble Alota Calories Vice Regent 13 LE SUISSE C 1987 Liloy Alp Me Please 24 ARONIA M 1984 Grey Dawn Amazer Liloy 15 ALL COME TRUE F 1986 Liloy Amazer 17 SPECTACULAR BY F 1986 Spectacular Bid Amazing Sister 559 TRILLIONAIRE M 1975 Vaguely Noble Amerigo's Fancy 330 MAGESTLIN M 1983 Majestic Light An Irish Colleen Globe 244 HOYAMOTION M 1983 J O Tobin April Bloom I'm Glad (ARG) 20 SHOWERS F 1984 Northern Baby April Edge 23 BABY SAS C 1987 Northern Baby Aransas 22 ALMOST HUMBLE C 1986 Vaguely Noble Aransas 2 ADIEU M 1972 Tompion Armoricana Dahar 408 RAINY PRINCESS M 1975 Rainy Lake Ask The Prince Dahar 27 NOBLE LILOY C 1986 Liloy Aura 28 ALLIONIA F 1984 Liloy Aura 579 VIOLE DE GAMBE (FR) M 1976 Luthier Aurambre (FR) Cozzene 30 L'AUST YOUTH C 1986 Youth Austwell 32 LILISH F 1987 Liloy -

HUNT for SILVER Silver Was $5 an Ounce and the 5000 Exchanges to Change the Rules in the Ounces Cost $25,000

-~ Mark Perlstein - Black Sta r HUNTFOR SILVER Gary Allen is author of None Dare Call It Conspiracy; The Rockefeller File ; Kissinger; Jimmy Carter/Jimmy Carter; Tax Target: Washington; and, Ted Kennedy: In Over His Head. He is an AMERICAN OPINION Contributing Editor. • NELSON BUNKER HUNT, fabled son television series. He is, in fact, a of the legendary billionaire H.L. happy combination of sober realist Hunt of Texas, has been called "Sil and idealistic visionary. He is a sober verfinger" by financial journalists realist because he understands' the eager to dramatize his silver invest perilous direction in which our civili ments in the purple ad hominems of zation has been headed - the politi a James Bond novel. Hunt is neither cal instability, the civil turmoil, the an eccentric villain out of James financial catastrophe of hyperinfla Bond nor a sinister schemer in the tion and moral bankruptcy. And he is mold of J.R. Ewing of the "Dallas" an idealistic visionary because he is DE CEMBER,1 980 1 ~ . The miners at right help to deliver annual world production of silver that for twenty years has been in the neighborhood of 300 million ounces, Meanwhile, silver consumption is run ning at 500 million ounces a year. The Hunts realized that as available reserves are con sumed the price of the metal must rise. working for a better world in which speculator in silver. Speculators are the people govern themselves and short-term players. They do not buy their economy without being victim their holdings to keep, as Hunt was ized by a paper aristocracy which doing and continues to do. -

THE STORY of SILVER Silver Prices for 200 Years

THE STORY OF SILVER Silver Prices for 200 Years This semi-log chart shows the annual average price per troy ounce of pure silver in U.S. dollars from 1792 through 2015 and some of the major events influencing the white metal during that period. The data are spliced from the following sources: 1) The U.S. Mint price from 1792–1833; 2) The average market price reported by the Department of the Mint, 1834–1909; 3) The average of monthly prices reported by the CRB database, 1910–1946; 4) The average of daily prices reported by the CRB database, 1947–2015. The annual average price in 1980 is lower than in 2011, even though the daily peak price ($50) was higher in 1980, because daily prices fell more precipitously during 1980 compared with 2011. Note: Because of inflation, the value of $1.29 in 1792 is equivalent to $31.30 in current dollars of 2011, when silver hit a peak of $48 (based on the consumer price index calculator from the EH.net website of the Economic History Association). By the Same Author Volcker: The Triumph of Persistence When Washington Shut Down Wall Street: The Great Financial Crisis of 1914 and the Origins of America’s Monetary Supremacy Financial Options: From Theory to Practice (coauthor) Principles of Money, Banking, and Financial Markets (coauthor) Financial Innovation (editor) Money (coauthor) Portfolio Behavior of Financial Institutions THE STORY OF SILVER HOW THE WHITE METAL SHAPED AMERICA AND THE MODERN WORLD WILLIAM L. SILBER PRINCET ON UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINCETON & OXFORD Copyright © 2019 by Princeton University -

Interview with Andrew F. Brimmer Former Member, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

Federal Reserve Board Oral History Project Interview with Andrew F. Brimmer Former Member, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System Date: July 13, 2007; July 27, 2007; and August 1, 2007 Location: Washington, D.C. Interviewers: David H. Small, Adrienne Hurt, Ben Hardaway, John C. Driscoll, and David Skidmore Federal Reserve Board Oral History Project In connection with the centennial anniversary of the Federal Reserve in 2013, the Board undertook an oral history project to collect personal recollections of a range of former Governors and senior staff members, including their background and education before working at the Board; important economic, monetary policy, and regulatory developments during their careers; and impressions of the institution’s culture. Following the interview, each participant was given the opportunity to edit and revise the transcript. In some cases, the Board staff also removed confidential FOMC and Board material in accordance with records retention and disposition schedules covering FOMC and Board records that were approved by the National Archives and Records Administration. Note that the views of the participants and interviewers are their own and are not in any way approved or endorsed by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Because the conversations are based on personal recollections, they may include misstatements and errors. ii Contents July 13, 2007 (First Day of Interview) ......................................................................................... 1 Family History