Mesopotamian Art Last Week I Dealt with the Protoliterate Period and the Early Dynastic Period, and I Promised to Show You A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Neo-Babylonian Empire New Babylonia Emerged out of the Chaos That Engulfed the Assyrian Empire After the Death of the Akka

NAME: DATE: The Neo-Babylonian Empire New Babylonia emerged out of the chaos that engulfed the Assyrian Empire after the death of the Akkadian king, Ashurbanipal. The Neo-Babylonian Empire extended across Mesopotamia. At its height, the region ruled by the Neo-Babylonian kings reached north into Anatolia, east into Persia, south into Arabia, and west into the Sinai Peninsula. It encompassed the Fertile Crescent and the Tigris and Euphrates River valleys. New Babylonia was a time of great cultural activity. Art and architecture flourished, particularly under the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II, was determined to rebuild the city of Babylonia. His civil engineers built temples, processional roadways, canals, and irrigation works. Nebuchadnezzar II sought to make the city a testament not only to Babylonian greatness, but also to honor the Babylonian gods, including Marduk, chief among the gods. This cultural revival also aimed to glorify Babylonia’s ancient Mesopotamian heritage. During Assyrian rule, Akkadian language had largely been replaced by Aramaic. The Neo-Babylonians sought to revive Akkadian as well as Sumerian-Akkadian cuneiform. Though Aramaic remained common in spoken usage, Akkadian regained its status as the official language for politics and religious as well as among the arts. The Sumerian-Akkadian language, cuneiform script and artwork were resurrected, preserved, and adapted to contemporary uses. ©PBS LearningMedia, 2015 All rights reserved. Timeline of the Neo-Babylonian Empire 616 Nabopolassar unites 575 region as Neo- Ishtar Gate 561 Amel-Marduk becomes king. Babylonian Empire and Walls of 559 Nerglissar becomes king. under Babylon built. 556 Labashi-Marduk becomes king. Chaldean Dynasty. -

Forgetting the Sumerians in Ancient Iraq Jerrold Cooper Johns Hopkins University

“I have forgotten my burden of former days!” Forgetting the Sumerians in Ancient Iraq Jerrold Cooper Johns Hopkins University The honor and occasion of an American Oriental Society presidential address cannot but evoke memories. The annual AOS meeting is, after all, the site of many of our earliest schol- arly memories, and more recent ones as well. The memory of my immediate predecessor’s address, a very hard act to follow indeed, remains vivid. Sid Griffiths gave a lucid account of a controversial topic with appeal to a broad audience. His delivery was beautifully attuned to the occasion, and his talk was perfectly timed. At the very first AOS presidential address I attended, the speaker was a bit tipsy, and, ten minutes into his talk, he looked at his watch and said, “Oh, I’ve gone on too long!” and sat down. I also remember a quite different presi- dential address in which, after an hour had passed, the speaker declared, “I know I’ve been talking for a long time, but since this is the first and only time most of you will hear anything about my field, I’ll continue on until you’ve heard all I think you ought to know!” It is but a small move from individual memory to cultural memory, a move I would like to make with a slight twist. As my title announces, the subject of this communication will not be how the ancient Mesopotamians remembered their past, but rather how they managed to forget, or seemed to forget, an important component of their early history. -

The Quest for Order O Mesopotamia: “The Land Between the Rivers”

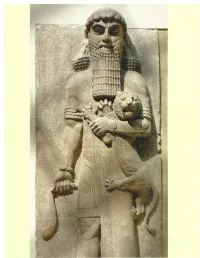

A wall relief from an Assyrian palace of the eighth century B.C.E. depicts Gilgamesh as a heroic figure holding a lion. Page 25 • The Quest for Order o Mesopotamia: “The Land between the Rivers” o The Course of Empire o The Later Mesopotamian Empires • The Formation of a Complex Society and Sophisticated Cultural Traditions o Economic Specialization and Trade o The Emergence of a Stratified Patriarchal Society o The Development of Written Cultural Traditions • The Broader Influence of Mesopotamian Society o Hebrews, Israelites, and Jews o The Phoenicians • The Indo-European Migrations o Indo-European Origins o Indo-European Expansion and Its Effects o EYEWITNESS: Gilgamesh: The Man and the Myth B y far the best-known individual of ancient Mesopotamian society was a man named Gilgamesh. According to historical sources, Gilgamesh was the fifth king of the city of Uruk. He ruled about 2750 B.C.E.—for a period of 126 years, according to one semilegendary source—and he led his community in its conflicts with Kish, a nearby city that was the principal rival of Uruk. Historical sources record little additional detail about Gilgamesh's life and deeds. But Gilgamesh was a figure of Mesopotamian mythology and folklore as well as history. He was the subject of numerous poems and legends, and Mesopotamian bards made him the central figure in a cycle of stories known collectively as theEpic of Gilgamesh. As a figure of legend, Gilgamesh became the greatest hero figure of ancient Mesopotamia. According to the stories, the gods granted Gilgamesh a perfect body and endowed him with superhuman strength and courage. -

Sargon of Akkad: the Akkadian Empire Around the Year 2350

Sargon of Akkad: The Akkadian Empire Around the year 2350 B.C.E., a powerful Mesopotamian leader named Sargon took control of northern and southern Mesopotamia and established the world’s first empire. An empire brings together many different peoples and lands under control of one ruler, called an emperor. Your task is to analyze the documents throughout this assignment and formulate a complete understanding of Sargon and his Akkadian Empire. How was Sargon able to establish this empire? Why did his empire last? Why should the Akkadian Empire be considered important to world history? WHAT IMPORTANT INFORMATION DO WE LEARN ABOUT DOCUMENT #1 SARGON AND HIS EMPIRE FROM DOCUMENT 1? DOCUMENTS 2 &3 WHAT IMPORTANT INFORMATION DO WE LEARN ABOUT SARGON AND HIS EMPIRE FROM DOCUMENTS 2/3? Sargon’s Military Force DOCUMENT #4 WHAT IMPORTANT INFORMATION DO WE LEARN ABOUT SARGON AND HIS EMPIRE FROM DOCUMENT 4? As with most early Mesopotamian kings, we know little about Sargon the Great. Cuneiform records indicate that in his 50-year reign, he fought no fewer than 34 wars. One account suggests that his core military force numbered 5,400 men; if that account is accurate, then Sargon’s standing army at full mobilization would have constituted the largest army of the time by far. Unlike leaders of the previous wars between rival city-states, Sargon created a national empire that would have required a much larger force than usual to sustain it, and he and his heirs did for 300 years. Sargon faced the same problem as Alexander the Great would eventually face. -

The Birth of Gilgamesh

THE BIRTH OF GILGAMEÍ (Ael. NA XII.21) A case-study in literary receptivity* Wouter F.M. Henkelman (Leiden) Rapunzel, Rapunzel, Laß mir dein Haar herunter! 1. Greek and Near Eastern literature 1.1. Das zaubernde Wort – In a letter to Helene von Nostitz, Rainer Maria Rilke wrote about the Babylonian Gilgameß Epic, a translation of which he had just read in the Inselbücherei series. According to Rilke the epic contained “Maße und Gestalten die zum Größesten gehören, was das zaubernde Wort zu irgendeiner Zeit gegeben hat. (...) Hier ist das Epos der Todesfurcht, entstanden im Unvordenklichen unter Menschen, bei denen zuerst die Trennung von Tod und Leben definitiv und verhängnisvoll geworden war.”1 The literary quality of the Gilgameß epic is indeed striking – the celebrated friendship of Gilgameß and Enkidu and the sorrow of Gilgameß over the latter’s death are pictured in a compelling drama of such powerful imagery that it has even outlived its own bold image of eternity, the mighty walls of Uruk. Ever since its rediscovery, now some 130 years ago, the epic has stirred the minds of its many readers and – as is the hallmark of any true work of art – found just as many interpretations. It may come as no great surprise, then, that in the debate on Oriental ‘influences’ or (better) Near Eastern or ‘West-Asiatic’ elements in Greek literature the Gilgameß Epic has continuously held a central place. This is not the place to review the long and, at times, tediously unproductive debate between the modern philobarbaroi and the defenders of the romantic vision of a monolithic Hellas rising from the lowly dusts of time to a sublime state of ‘edle Einfalt’ all by itself and by itself alone. -

Sargon of Akkade and His God

Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hung. Volume 69 (1), 63–82 (2016) DOI: 10.1556/062.2016.69.1.4 SARGON OF AKKADE AND HIS GOD COMMENTS ON THE WORSHIP OF THE GOD OF THE FATHER AMONG THE ANCIENT SEMITES STEFAN NOWICKI Institute of Classical, Mediterranean and Oriental Studies, University of Wrocław ul. Szewska 49, 50-139 Wrocław, Poland e-mail: [email protected] The expression “god of the father(s)” is mentioned in textual sources from the whole area of the Fertile Crescent, between the third and first millennium B.C. The god of the fathers – aside from assumptions of the tutelary deity as a god of ancestors or a god who is a deified ancestor – was situated in the centre and the very core of religious life among all peoples that lived in the ancient Near East. This paper is focused on the importance of the cult of Ilaba in the royal families of the ancient Near East. It also investigates the possible source and route of spreading of the cult of Ilaba, which could have been created in southern Mesopotamia, then brought to other areas. Hypotheti- cally, it might have come to the Near East from the upper Euphrates. Key words: religion, Ilaba, royal inscriptions, Sargon of Akkade, god of the father, tutelary deity, personal god. The main aim of this study is to trace and describe the worship of a “god of the fa- ther”, known in Akkadian sources under the name of Ilaba, and his place in the reli- gious life of the ancient peoples belonging to the Semitic cultural circle. -

Mesopotamian Society Was a Man the TRANSITION Named Gilgamesh

y far, the most familiar individual of ancient Mesopotamian society was a man THE TRANSITION named Gilgamesh. According to historical sources, Gilgamesh was the fifth TO AGRICULTURE king of the city of Uruk. He ruled about 2750 B.C. E., and he led his community The Paleolithic Era in its conflicts with Kish, a nearby city that was the principal rival of Uruk. The Neolithic Era Gilgamesh was a figure of Mesopotamian mythology and folklore as well as his tory. He was the subject of numerous poems and legends, and Mesopotamian bards THE QUEST FOR ORDER made him the central figure in a cycle of stories known collectively as the Epic of Mesopotamia: "The Land Gilgamesh. As a figure of legend, Gilgamesh became the greatest hero figure of between the Rivers" ancient Mesopotamia. According to the stories, the gods granted Gilgamesh a per The Course of Empire fect body and endowed him with superhuman strength and courage. The legends declare that he constructed the massive city walls of Uruk as well as several of the THE FORMATION OF A COMPLEX SOCIETY city's magnificent temples to Mesopotamian deities. AND SOPHISTICATED The stories that make up the Epic of Gi/gamesh recount the adventures of this CULTURAL TRADITIONS hero and his cherished friend Enkidu as they sought fame. They killed an evil mon Economic Specialization ster, rescued Uruk from a ravaging bull, and matched wits with the gods. In spite of and Trade their heroic deeds, Enkidu offended the gods and fell under a sentence of death. The Emergence of a His loss profoundly affected Gilgamesh, who sought The Epic of Gilgamesh Stratified Patriarchal Society for some means to cheat death and gain eternal www.mhhe.com/ • bentleybrief2e The Development of Written life. -

1. Ebla and the Old Testament It Was in Neolithic Times That The

EBLA, UGARIT AND THE OLD TESTAMENT* Cyrus H. GORDON** 1. Ebla and the Old Testament It was in Neolithic times that the two basic sources of producing food were developed: agriculture and animal husbandry. The surplus of food raised by the farmers and herdsmen made it possible to form communities able to support guilds for special functions: building; weaving wool and linen; manu- facturing wares made of cloth, stone, bone and wood; trading; priestcraft; etc. It was during the Neolithic Age that ceramics began on their enduring course. In the Chalcolithic Age (4000-3000 B. C.), copper, silver and gold as well as stones were worked. Also the beginning of monumental architecture (like the ziggurats of Mesopotamia), fine art (e. g., seal cylinders), and the seeds of writing. The last item refers to numerals and commodities which were indicated ideographically and which developed into Mesopotamian writing around 3000 B. C. at the dawn of the Early Bronze Age.(1) Intellectual urban centers flourished throughout Sumer and Akkad, and spread, albeit in modified form, wherever Mesopotamian tradesmen and armies went. The largest archives of the Early Bronze Age (3000-2000) come not from Mesopotamia but from Syria. An Italian expedition, under the directorship of Professor Paulo Matthiae, has unearthed so far about 15,000 cuneiform tablets dating from the early 23rd century B. C. The principle language is a new border dialect with affinities to East Semitic (=Akkadian or Assyro-Babylonian) and to Northwest Semitic (=Hebrew, Aramaic, Ugaritic). Although the date is a millennium earlier than the Ugaritic tablets and therefore long before the earliest dates ever seriously suggested for Abraham, the Ebla Archives have a bearing on the Old Testament: linguistically and culturally. -

Sargon of Akkad: Rebel and Usurper in Kish

Chapter 3 Sargon of Akkad: Rebel and Usurper in Kish Marlies Heinz When Sargon of Akkad (ca. 2340–2280 b.c.) seized power in Kish, it was the begin- ning of a reign that would restructure the entire political landscape of the Near East. Legend has it that Sargon was the son of a high-ranking priestess who immediately after his birth placed him in a basket and abandoned him to the Euphrates.1 A man named Aqqi discovered the baby, pulled him out of the river, and adopted him. Sar- gon became a gardener at his father’s estate. It is not known in detail how he ended up at the royal court in Kish. Traditionally it is believed that he was taken there by the town goddess, Ishtar, who had seen him in his father’s garden. Sargon did not belong to the traditional elite of Kish; he did not know anything about his origins. At court he became the king’s cupbearer. From this position, he re- belled against the authorities and deprived the legitimate (!) king, Urzababa, of his power with the approval of, and by the will of, the deities An, Enlil, and Ishtar. Sargon became Urzababa’s successor and sealed his accession to the throne by taking the title Sharru-kin (= Sargon), which means ‘the legitimate king’. At the beginning of his reign, Sargon changed most of the traditional political structure of Kish. The “old ones” (intimates of the former king?) and the temple priests were deprived of their power, and the palace took over the economic domains of the temples. -

Summer and Akkad Geographical Context the Fertile Crescent Ubaid Culture

Summer and Akkad Geographical Context The Fertile Crescent Ubaid Culture • Roughly 6000 – 3500 BC. • First pottery • First settled ‘towns’ • “The creators of the Ubaid… were heirs to cumulative developments in the long history of agricultural village life in the Near East” (Hout 1992, 188). Sumerians Arrived from Asia ca 3900 – 3500 Unique language that resembles Turkic and Hungarian • Brought (?) Copper tech. • Applied to irrigation • Kish or Uruk earliest city • Competing city states • Legend of the Flood • Legends of divine parentage Sumer Kuhrt • Kuhrt, Amelie. 1995. The Ancient Near East. • Cultural parallelism • Semitic words in Sumerian texts • Diversity of land ownership • Monarchy more than theocracy • Contra Edgar et al. City Rivalries • Eannatum, king of Lagash • Ca. 2450 BC • Conquered the cities of Sumer • Vulture Stele commemorates victory over Enakalle of Umma The Vulture Stele The Vulture Stele • Winter, Irene. 1985. After the Battle is Over: The “Stele of the Vultures” and the Beninning of Historical Narrative in the Art of the Ancient Near East. Studies in the History of Art 16, Symposium Papers IV: Pictoral Narrative in Antiquity and the Middle Ages: 11 – 32. Sargon of Akkad (Agade) • Lugalzagesi • Ruler of Uruk • Hegemon of Sumerian empire • Sargon • Ruler of Akkad (2296 - 2240) • Semitic • Begins a literary tradition of pasts remembered (recreated). The Dynasty of Sargon • Sargon (2296 -2240) • Rimush (2239 – 2230) • Manishtushu (2229 – 2214) • Naram Sin (2213 – 2176) • Sharkalisharri (2175 – 2150) • …but these dates are disputed Ur – The Sumerian Renaissence • Utuhegal (2119 – 2113) • Ur-Nammu (2112 – 2095) • Shulgi (2094 – 2047) • Amar –Sin (2046 – 2038) • Shu-Sin (2037 – 2027) • Ibbi-Sin (2026 – 2004) Material Record Cylinder Seals Cuneiform Bronze • Ca. -

Thesis, Revised Copyright

Views of Epic Transmission in Sargonic Tradition and the Bellerophon Saga By Copyright 2012 Cynthia Carolyn Polsley Cynthia C. Polsley Submitted to the graduate degree program in Classics and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Stanley Lombardo ________________________________ Anthony Corbeill ________________________________ Molly Zahn Date Defended: February 13, 2012 The Thesis Committee for Cynthia C. Polsley certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Views of Epic Transmission in Sargonic Tradition and the Bellerophon Saga ________________________________ Chairperson Stanley Lombardo Date approved: February 15, 2012 ii Abstract One of the most memorable tales in Homer’s Iliad is that of Bellerophon, the Corinthian hero sent as courier with a message deceitfully intended to arrange his death. A similar story is related in the Sumerian Sargon Legend of the eighteenth-century B.C.E., which tells of how Sargon of Akkad seized the kingdom of Uruk by divine aid. The motif of a treacherous letter is not the only similarity between general stories regarding Sargon and Bellerophon. Other shared themes include blood pollution, interactions with a queen, divine escort, and a restless wandering. Tales about Sargon and Bellerophon are disseminated across cultures. Sumerian and Akkadian texts describing Sargon’s exploits have been found in Egypt, Syria, and Anatolia, while Bellerophon’s adventures are described by storytellers of Greece and Rome. Beginning with the Sargon Legend and Homer’s Bellerophon, I explore the two narrative traditions primarily as case studies for epic transmission. I furthermore propose that cultural interaction and a complex network of oral and written storytelling contributed to the transmission of the traditions and motifs. -

Sargon II, King of Assyria

SARGON II, KING OF ASSYRIA Press SBL A RCHAEOLOGY AND BIBLICAL STUDIES B rian B. Schmidt, General Editor Editorial Board: Aaron Brody Annie Caubet Billie Jean Collins Israel Finkelstein André Lemaire Amihai Mazar Herbert Niehr Christoph Uehlinger Number 22 Press SBL SARGON II, KING OF ASSYRIA Josette Elayi Press SBL Atlanta C opyright © 2017 by Josette Elayi A ll rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permit- ted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the Rights and Permissions Office,B S L Press, 825 Hous- ton Mill Road, Atlanta, GA 30329 USA. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Elayi, Josette, author. Title: Sargon II, King of Assyria / by Josette Elayi. Description: Atlanta : SBL Press, 2017. | Series: Archaeology and biblical studies ; number 22 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2017009197 (print) | LCCN 2017012087 (ebook) | ISBN 9780884142232 (ebook) | ISBN 9780884142249 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781628371772 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Sargon II, King of Assyria, –705 B.C. | Assyria—History. | Assyria—His- tory, Military. Classification: LCC DS73.8 (ebook) | LCC DS73.8 .E43 2017 (print) | DDC 935/.03092 [B] —dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017009197 Press Printed on acid-free paper. SBL C ontents A uthor’s Note ...................................................................................................vii Abbreviations ....................................................................................................ix Introduction .......................................................................................................1 1. Portrait of Sargon .....................................................................................11 2.