Public Sector Duplication of Small Business Administration Loan And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Financing Your Business Financial Options and Funding Sources

FINANCING YOUR BUSINESS Financial Options and Funding Sources 25 • Financing Options » SBA’s Loan Guaranty Programs 26 » Commercial Loans 29 » SBA Micro Lenders 29 30 • Funding Sources » Arizona’s Incentives, Programs and Grants 31 » Funding for Innovation and Technology Companies 32 While every effort has been made to ensure the reliability of the information presented in this publication, the Arizona Commerce Authority cannot guarantee the accuracy of this information due to the fact that much of the information is created by external sources. Changes/updates brought to the attention of the Arizona Commerce Authority and verified will be corrected in future editions. 3 The Access to Capital Academy presented by the Phoenix Community & Economic Development and Investment Corporation (PCDIC) – helps entrepreneurs learn how to approach potential lenders with confidence and an increased chance at securing loans. 24 AZ EE FINANCING OPTIONS FI NAN CI NG YOUR There are several sources to consider when looking for three years of business tax returns, etc.) and financing. It is important to explore all of your options prospective (projections) basis. before making a decision. Collateral – property pledged by a borrower to protect the interest of the lender. By putting up collateral, you B The primary source of capital for most new businesses US show that you are committed to the success of your come from personal savings and other forms of personal I NESS resources such as friends and family, when starting out. business. While credit cards often are used to finance business A financial institution avoids making loans without needs, there may be better options available, even for F collateral. -

Personal Vs. Business Credit

The Keys to Successful Small Business Ownership, Finance and Credit™ Client Curriculum - Personal vs. Business Credit Small Business Owner Financial With financial support from: Education brought to you by: Sharpen Your Financial Focus® The Keys to Successful Small Business Ownership, Finance and Credit™ National Foundation for Credit Counseling® (NFCC®) - Small Business Owner Counseling Program Client Workbook Version 6.0 March 26, 2018 INTRODUCTION Welcome! It is our goal you find this material helpful as it was hand selected to address some of the most common challenges faced by the self-employed or small business owners. We aim for this content to complement budget counseling sessions for people like you engaged with a member agency of the National Foundation for Credit Counseling® (NFCC®) across the U.S. Whether you just started on a self-employment journey, have a business on the side or have dreams of serving millions, you are important to our national economy and local community by creating a job for yourself or others. It is our hope this program empowers you to make informed decisions about being self-employed and a small business owner by providing you access to a NFCC counselor, information, resources, and tools. As you develop a greater understanding of personal and business finance best practices, you can choose the best course of action to meet your goals. We would like to thank and acknowledge TD Bank, America’s Most Convenient Bank®, and the TD Charitable Foundation, the charitable giving arm of TD Bank, for their support of the NFCC Small Business Owner Financial Counseling and Education Program supporting Small Business Owner Financial Wellness. -

Can I Qualify for a Business Loan SBDC

Can I Qualify for a Business Loan? Whether you are applying for an SBA loan or a traditional bank loan, there are certain factors that improve your ability to obtain financing. This self-test is designed to assist you in understanding important issues that lenders consider when making a decision on a small business loan. Do you have a good personal credit history? Research indicates that good personal credit history is one of the most important factors in identifying borrowers that will repay their business loans. When a lender makes a decision on a small business loan, he/she will consider the personal credit history of the borrower. A bad credit history can be the basis for denial for a small business loan. a) If you do not have a recent credit report, find out about ordering one by go to the following web site: http://www.ftc.gov/freereports You can also contact the individual organizations: TransUnion (www.transunion.com), Experian (www.experian.com), or Equifax (www.equifax.com). If you have credit problems but they can be explained by a one-time incident such as a medical problem, provide specific information, as an addendum to your loan proposal, to a potential lender about the problem and how it has been rectified. b) If you have filed for bankruptcy in the past 7 years (10 yrs for an SBA loan), or have slow payments, collections, etc. then it may be difficult to obtain financing now. If your poor credit history can be explained by a particular incident, supply information on the situation and how you attempted to repair past credit problems. -

The Arundel Business Loan Fund

Anne Arundel Economic Development Corporation Economic Development Revenue Bonds The ABL Fund is a viable non-bank alternative source of financing ready and Anne Arundel County encourages private- able to assist small businesses in Anne sector financing for economic development Arundel County. The ABL Fund’s partners projects through the issuance of private are: the U.S. Small Business Administration, The Arundel Business activity revenue bonds. Tax-exempt bonds the Maryland Industrial Development Loan Fund Financing Authority (MIDFA), The Maryland provide access to long term capital markets an SBA Lender for fixed-asset financing at tax-exempt Small Business Development Financing rates. Federal tax law limits eligibility to Authority (MSBDFA) and 19 banks Guidelines for a Small Business Loan • Bank of America • Bay Bank • Branch Banking & Trust (BB&T) • Essex Bank • First Mariner Bank • First National Bank • M&T Bank • Old Line Bank • PNC Bank manufacturing facilities, 501(c)(3) non- • Howard Bank profit organizations, and certain energy • Revere Bank projects. Additional limitations apply, • SECU depending on the specific transaction. • Sandy Spring Bank • Severn Savings Bank Most importantly, you have a • SunTrust Bank resource at AAEDC. Contact us • TD Bank with questions and for details. • The Bank of Glen Burnie • The Columbia Bank The Anne Arundel Economic Development Corporation mission is to serve business needs and to increase Anne Arundel County’s economic base through job growth and investment. For more information about the -

FFMSR-6 Guaranteed Loan System Requirements

December 1993 FFMSR-4 .... ... ... .... ...... .... ... ............. ,: .................. .:. : : .: .................. :; ““’ “’ ... ....... ,., ........ ., . ...... :, ., :. :. .: :. : .:. _.: :: :, .......... .: .:. .... :. ....... ., ............. ,: ........... .: ............ ........ ?. ...... :._ . ., ....... ., . : : : ... :, : ..... ...... .:. ............. .................................... .: ...... ... .: : .......... ......... ....... .... : ... :: :, :: ...... ... ...... ..... > ... .... :. ., . ..... :. ......... .: :. .:. :> ..... : :: : .. .......... ,: .... ‘:: ,: ...... .: .......... ,: .. :, ., >, ........... ;: .: .... .................. .: .... :., ....... .,., : ‘: :. ..... : ..... .:: ...... :, ._ :_> : .: > : .: > ... .: .:i .......... .: .. ..:. .:: ...... : ... .: ...... ............. > ......... ., ..... .:. :. ...... :.,: : ., .:. : ... .:.: .. : ,: : > :,,.: .................. :. : .:- .: ... ‘: .......... ........ .:. .......... ... ............ .:. ,., ., .................... ........ .:_, ... ., .:, .: ._I. : : .: ... ,:, : : ... .: .. :. : .: ..... .................... .: : : ........... ........ .> :,,, >,, .. 1.: ,,_:, :: .I.<. ......... > 1.: : : .I,., .> > .: .. > .: > ,:.> > : : ... > .. > .: > .: ....... ...... .QC, .............. ... ..... ............ ..... .... : > . : .: :. ,: ., .: : ,.: : .: :. : .: > : > ..: .: .. > : .. .: .: .. .> .: : .: .. ........... ............... >, : .............. : .: ..... ......... > . : . .: ......... ........ .:.: : :. : ............. ,:.:: ...... .......... -

Business Financing Opportunities

1st Stop Business Connection www.development.ohio.gov/onestop Revised 08/012010 Business Financing Opportunities Table of Contents Sections Page Number Money 2 -Calculate how much you need Financing 3 - 4 -Types of financing -Business and loan proposals Glossary of Business Terms 5 -A head start on your business vocabulary Federal Loan Programs 6 - 11 State Loan Programs 12 – 17 State Energy Programs 18 - 20 Small Business Development Center Directory 21 -Find the SBDC nearest to you 1 MONEY One of the toughest parts of starting a small business is finding the necessary capital. In other words: Where do you find the money? This publication will help you figure out where to find the money you need to start and run a small business. First, you must know how much money you'll need. Write down the equipment you have and the equipment and inventory you need. How much will it cost to buy or lease the equipment and inventory? Equipment you already have Equipment and inventory you must purchase or lease Cost _______________________ ___________________________________________ $___________ _______________________ ___________________________________________ $___________ _______________________ ___________________________________________ $___________ _______________________ ___________________________________________ $___________ _______________________ ___________________________________________ $___________ TOTAL $ __________ Now, it's time to estimate how much it will cost to keep your business running: Business space $______________________________ -

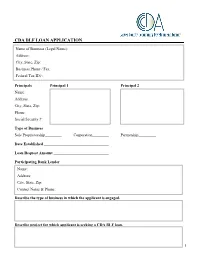

Cda Blf Loan Application

CDA BLF LOAN APPLICATION NameName of of Business Business (Legal (Legal Name): Name): Address:Address: City,City, State, State, Zip: Zip: BusinessBusiness Phone Phone / / Fax: Fax: FederalFederal Tax Tax ID ID#: #: Principals Principal 1 Principal 2 Name: Address: City, State, Zip: Phone: Social Security #: Type of Business Sole Proprietorship Corporation Partnership Date Established Loan Request Amount Participating Bank Lender Name:Name: Address:Address: City,City, State, State, Zip: Zip: ContactContact Person: Name & Phone: Contact Phone: Describe the type of business in which the applicant is engaged. Describe project for which applicant is seeking a CDA BLF loan. 1 EXISTING BUSINESS FINANCING OBLIGATIONS (Date of most recent balance sheet) ORIGINAL AMOUNT/ PRESENT MATURITY INTEREST MONTHLY PAYMENT CREDITOR NAME DATE BALANCE DATE RATE PAYMENT STATUS PROJECT FINANCING SUMMARY SOURCE AND USE OF FUNDS CDA BLF BANK EQUITY OTHER OTHER TOTAL Property Acquisition Site Improvement Building Renovation New Construction Machinery & Equipment Working Capital Inventory Debt Refinancing Other Other Total PROPOSED FINANCING TERMS CDA BLF BANK EQUITY OTHER OTHER TOTAL Amount $ $ $ $ $ $ % of Project Cost % % % % % % Term (years) yrs yrs yrs yrs yrs yrs Interest Rate % % % % % % Debt Service yrs yrs yrs yrs yrs yrs Lien Position Collateral Guarantee ADDITIONAL REQUIRED INFORMATION The information included in the attached “Exhibit A – Application Exhibits” shall also be provided to TCCCF as part of this loan application 2 I declare that the information provided on this application and the accompanying exhibits is true and complete to the best of my knowledge. I understand that the Carver County CDA Business Loan Fund has the right to verify this information and will be in contact with those individuals and institutions involved in the proposed project. -

APPLICATION for LOAN GUARANTEE (Business and Industry and Rural Energy of America Programs)

Form RD 4279-1 Position 3 FORM APPROVED (Rev. 10-08) OMB No. 0570-0017 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE OMB No. 0570-0067 RURAL DEVELOPMENT APPLICATION FOR LOAN GUARANTEE (Business and Industry and Rural Energy of America Programs) Section 1001 of Title 18, United States Code provides: “Whoever, in any matter within the jurisdiction of any department or agency of the United States knowingly and willfully falsifi es, conceals or covers up by any trick, scheme, or device a material fact or makes any false, fi citious or fraudulent statements or representations, or makes or uses any false writing or document knowing the same to contain any false, fi citious or fraudulent statement or entry shall be fi ned under this title or imprisoned not more that fi ve years or both. CERTIFICATION: Information contained below and in attached exhibits is true and complete to my best knowledge. (Misrepresentation of material facts may be the basis for denial of credit by the United States Department of Agriculture (“USDA”) .) PART A: Completed By Borrower 1. AMOUNT OF LOAN 2. NAME OF BORROWER(S) 3. ADDRESS (Include Zip Code) $ 4. CONTACT PERSON 5. TELEPHONE NUMBER (Include Area Code) 6. TAX ID# OR SOCIAL SECURITY# FOR ( ) INDIVIDUALS 7. PROJECT LOCATION (Town/City) 8. POPULATION9. COUNTY 10. TYPE OF BORROWER 11. NASIC Proprietorship Cooperative CODE 12. DATE BUSINESS ESTABLISHED 13. DUNS Number Partnership Indian Tribe Corporation Political Subdivision 14. a. THIS PROJECT IS 15. IF BORROWER IS AN INDIVIDUAL 16. HAS BORROWER OR RELATED INDI- (Item 10 checked proprietorship) VIDUAL EVER BEEN IN RECEIVERSHIP An expansion New Business OR BANKRUPTCY? YES NO A. -

Dod Financial Management Regulation Volume 12, Chapter 4 4

DoD Financial Management Regulation Volume 12, Chapter 4 CHAPTER 4 CREDIT MANAGEMENT 0401 OVERVIEW 040101. Purpose. This chapter establishes the policy and procedures for credit management within the Department of Defense. The polices and procedures for credit programs reflect the requirements of the Federal Credit Reform Act of 1990. The Federal Credit Reform Act of 1990 is found at Title V of the Congressional Budget Act of 1974, as amended by section 13201 of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990. The major purposes of the Act are to: • measure more accurately the costs of credit programs; • place the cost of credit programs on a budgetary basis equivalent to other Federal spending; • encourage the delivery of benefits in the form most appropriate to the needs of beneficiaries; and • improve the allocation of resources among credit programs and between credit and other spending programs. 040102. General. The policies set forth in this chapter apply to direct loan obligations and loan guarantee programs. The chapter provides implementing guidance for “Credit Apportionment and Budget Execution,” found within the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Circular No. A-34. It also implements “Accounting for Direct Loans and Loan Guarantees,” Statement of Federal Financial Accounting Standards Number 2. 0402 STANDARDS 040201. Explanation. The specific accounting standards for each category type of loans, are discussed in the subsequent sections of this Volume. These standards concern the recognition and measurement of direct loans, the liability associated with loan guarantees, and the cost of direct loans and loan guarantees. (Figure 4-1 and 4-2 provides examples the credit refortm cash flows for direct and guaranteed loans) The standards apply to direct loans and loan guarantees on a group basis, such as a cohort or a risk category, Section 0410 Credit Reform Accounts and Definitions, provides definitions for these categories. -

Chapter 9: Income Analysis 7 Cfr 3555.152

HB-1-3555 CHAPTER 9: INCOME ANALYSIS 7 CFR 3555.152 9.1 INTRODUCTION The lender is responsible to confirm applicants and households meet eligibility criteria for the Single Family Housing Guaranteed Loan Program (SFHGLP). Lenders must calculate and document annual, adjusted, and repayment income. The guidance provided applies to both manually underwritten loans and loans that utilize the Agency’s automated underwriting system, GUS. SECTION 1: ELIGIBILITY INCOME 9.2 OVERVIEW The SFHGLP assists very-low, low, and moderate-income households. Therefore, the lender must certify that any household that requests a loan guarantee does not exceed the adjusted annual income threshold for the applicable state and county where the dwelling is located. The Agency provides income eligibility information in Appendix 5 of this Handbook to lenders and updates the limits as they are revised. This section assists lenders to analyze income types, complete income calculations (annual, adjusted, and repayment), and document the income with acceptable verifications. Documentation of income calculations should be provided on Attachment 9-B, or the Uniform Transmittal Summary, (FNMA FORM 1008/FREDDIE MAC FORM 1077), or equivalent. Attachment 9-C provides a case study to illustrate how to properly complete the income worksheet. A public website is available to assist in the calculation of annual and adjusted annual income at: http://eligibility.sc.egov.usda.gov/eligibility/. 9.3 ANNUAL INCOME [7 CFR 3555.152(B)] Annual income will include all eligible income sources from all adult household members, not just parties to the loan note. The annual income for the household will be used to calculate the adjusted annual household income. -

The Role of Public Debt Managers in Contingent Liability Management

THE ROLE OF PUBLIC DEBT MANAGERS IN CONTINGENT LIABILITY MANAGEMENT SELECTED COUNTRY PRACTICES This document is published as an annex to an OECD working paper on "The role of public debt managers in contingent liability management".1 It presents the contingent liability management frameworks and practices in seven countries – Brazil, Denmark, Iceland, Mexico, South Africa, Sweden and Turkey – that are members of the OECD Task Force on Contingent Liabilities and Public Debt Management.2 These country cases provide detailed information on the: organisational structure of the Debt Management Office (DMO) main sources of contingent liabilities role of the DMO in the area of contingent liabilities – management, measurement, monitoring and reporting. The experiences of public debt managers in task force countries shed light on the different implementation and policy frameworks. These differences underline the difficulty of advising on a single set of roles for public debt managers. 1 "The role of public debt managers in contingent liability management", OECD Working Papers on Sovereign Borrowing and Public Debt Management, No. 8, OECD Publishing, Paris. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/93469058-en. 2 The OECD Working Party on Public Debt Management (WPDM) created a task force on Contingent Liabilities and Public Debt Management to report on country practices. The Members of the OECD task force are: Taşkın Temiz (Task Force Chair) and Fatih Kuz from the Turkish Treasury; Jose Franco Medeiros de Morais André Proite, Giovana Leivas Craveiro and Luiz Fernando Alves from the National Treasury of Brazil; Claus Johansen, Jacob Stæhr Wellendorph Ejsing and Nicolaj Hamann Christensen from Danmarks Nationalbank; Hákon Zimsen and Hafsteinn Hafsteinsson, from the Central Bank of Iceland; Jesus Ramiro Del Valle Rodriguez and Alejandro Diaz de Leon Carrillo from the Mexican Treasury; Mkhulu Maseko and Anthony Julies from the South African Treasury; Kritoffer Ekström and Eva Cassel from the Swedish National Debt Office (SNDO). -

Loan Guarantee Program

SSBCI PROGRAM PROFILE: LOAN GUARANTEE PROGRAM May 17, 2011 State Small Business Credit Initiative (SSBCI) U.S. Department of the Treasury LOAN GUARANTEE PROGRAM State Small Business Credit Initiative What is a Loan Guarantee Program? A Loan Guarantee Program enables small businesses to obtain term loans or lines of credit to help them grow and expand their businesses. The program provides a lender with the necessary security, in the form of a partial guarantee, for the lender to approve a loan or line-of-credit. What are the Credit and Loan Characteristics? Like all credit programs, a Loan Guarantee Program can be tailored to meet a state’s objectives. The table below describes key credit and loan characteristics that should be considered when designing a Loan Guarantee Program. Characteristics Description What kinds of borrowers • Determined by each state and may target specific industries, regions are eligible to and/or types of businesses, depending on the state’s objectives. participate? • Under SSBCI, lenders should target an average borrower size of 500 employees or less and not exceed a maximum borrower size of 750 employees. In practice, small businesses are typically much smaller than 500 employees. • Corporations, partnerships, and sole proprietorships are eligible, including non-profits and cooperatives. • SSBCI Policy Guidelines provide specific guidance on certain borrowers who are prohibited from participating in this program. What sizes of loans are • Under SSBCI, should target an average principal amount of $5 million or eligible? less and cannot exceed $20 million on any individual loan. In practice, the average small business loan is typically much less than $5 million.