Master's Thesis V2.1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music Video As Black Art

IN FOCUS: Modes of Black Liquidity: Music Video as Black Art The Unruly Archives of Black Music Videos by ALESSANDRA RAENGO and LAUREN MCLEOD CRAMER, editors idway through Kahlil Joseph’s short fi lm Music Is My Mis- tress (2017), the cellist and singer Kelsey Lu turns to Ishmael Butler, a rapper and member of the hip-hop duo Shabazz Palaces, to ask a question. The dialogue is inaudible, but an intertitle appears on screen: “HER: Who is your favorite fi lm- Mmaker?” “HIM: Miles Davis.” This moment of Black audiovisual appreciation anticipates a conversation between Black popular cul- ture scholars Uri McMillan and Mark Anthony Neal that inspires the subtitle for this In Focus dossier: “Music Video as Black Art.”1 McMillan and Neal interpret the complexity of contemporary Black music video production as a “return” to its status as “art”— and specifi cally as Black art—that self-consciously uses visual and sonic citations from various realms of Black expressive culture in- cluding the visual and performing arts, fashion, design, and, obvi- ously, the rich history of Black music and Black music production. McMillan and Neal implicitly refer to an earlier, more recogniz- able moment in Black music video history, the mid-1990s and early 2000s, when Hype Williams defi ned music video aesthetics as one of the single most important innovators of the form. Although it is rarely addressed in the literature on music videos, the glare of the prolifi c fi lmmaker’s infl uence extends beyond his signature lumi- nous visual style; Williams distinguished the Black music video as a creative laboratory for a new generation of artists such as Arthur Jafa, Kahlil Joseph, Bradford Young, and Jenn Nkiru. -

Adam4adam Asianfriend Dearly Beloved Bitch Behind Bars The

#1035 nightspots February 2, 2011 Adam4Adam AsianFriend Dearly Beloved Bitch Behind Bars 2 The Tongue Upright Citizen Chica Grande Jeepers Piepers 5sum Bent Boriqua Mr. Perfect Stranglers 5 1 Minerva Wrecks Circuit Daddy The Continental Shameless Boi-lesque ASS Da Gay Mayor Adam5Adam 1 Happy The richness Valentines, of Amanda Nightspots-style. Lepore. page 13 page 11 That Guy by Kirk Williamson In lieu of my column this week... [email protected] JOSEPH J. MAGGIO Joseph J. Maggio, age 58, passed away suddenly at his home on January 17. Best Friend and life partner of Jimmy Keup, Joe was the love of his life. Devoted son to the late Tina Riotto and the late Bartolo Maggio; brother of Maria (David) Guzik; and uncle to Mathew. Joe was a graduate of St. Partrick High School, received his Bachelor’s degree from Loyola University and his Master’s degree from Northeastern University. He began his long career as a teacher at Notre Dame High School for Girls in 1977. For the last 20 years, Joe taught math at St. Ignatius College Prep, and was honored to serve as coach of their Math Team. Among his other passions in life were real estate development, The Jackhammer Bar and The Ashland Arms Guest House. A Celebration of Life will take place Sat., February 12, 2011, from 2-4 p.m. at Unity in Chicago, 1925 W. Thome Avenue, Chicago, IL 60660. The celebration will then move to Jackhammer, 6406 N. Clark St. Donations to Alzheimer’s Association would be appreciated. PUBLISHER Tracy Baim ASSISTANT PUBLISHER Terri Klinsky nightspots MANAGING EDITOR -

A King Named Nicki: Strategic Queerness and the Black Femmecee

Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory ISSN: 0740-770X (Print) 1748-5819 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rwap20 A king named Nicki: strategic queerness and the black femmecee Savannah Shange To cite this article: Savannah Shange (2014) A king named Nicki: strategic queerness and the black femmecee, Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory, 24:1, 29-45, DOI: 10.1080/0740770X.2014.901602 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/0740770X.2014.901602 Published online: 14 May 2014. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 2181 View Crossmark data Citing articles: 2 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rwap20 Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory, 2014 Vol. 24, No. 1, 29–45, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0740770X.2014.901602 A king named Nicki: strategic queerness and the black femmecee Savannah Shange* Department of Africana Studies and the Graduate School of Education, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, United States This article explores the deployment of race, queer sexuality, and femme gender performance in the work of rapper and pop musical artist Nicki Minaj. The author argues that Minaj’s complex assemblage of public personae functions as a sort of “bait and switch” on the laws of normativity, where she appears to perform as “straight” or “queer,” while upon closer examination, she refuses to be legible as either. Rather than perpetuate notions of Minaj as yet another pop diva, the author proposes that Minaj signals the emergence of the femmecee, or a rapper whose critical, strategic performance of queer femininity is inextricably linked to the production and reception of their rhymes. -

Dan Hicks’ Caucasian Hip-Hop for Hicksters Published February 19, 2015 | Copyright @2015 Straight Ahead Media

Dan Hicks’ Caucasian Hip-Hop For Hicksters Published February 19, 2015 | Copyright @2015 Straight Ahead Media Author: Steve Roby Showdate : Feb. 18, 2015 Performance Venue : Yoshi’s Oakland Bay Area legend Dan Hicks performed to a sold-out crowd at Yoshi’s on Wednesday. The audience was made up of his loyal fans (Hicksters) who probably first heard his music on KSAN, Jive 95, back in 1969. At age 11, Hicks started out as a drummer, and was heavily influenced by jazz and Dixieland music, often playing dances at the VFW. During the folk revival of the ‘60s, he picked up a guitar, and would go to hootenannies while attending San Francisco State. Hicks began writing songs, an eclectic mix of Western swing, folk, jazz, and blues, and eventually formed Dan Hicks and his Hot Licks. His offbeat humor filtered its way into his stage act. Today, with tongue firmly planted in cheek, Hicks sums up his special genre as “Caucasian hip-hop.” Over four decades later, Hicks still delivers a unique performance, and Wednesday’s show was jammed with many great moments. One of the evenings highlights was the classic “I Scare Myself,” which Hicks is still unclear if it’s a love song when he wrote it back in 1969. “I was either in love, or I’d just eaten a big hashish brownie,” recalled Hicks. Adding to the song’s paranoia theme, back-up singers Daria and Roberta Donnay dawned dark shades while Benito Cortez played a chilling violin solo complete with creepy horror movie sound effects. -

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data As a Visual Representation of Self

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Design University of Washington 2016 Committee: Kristine Matthews Karen Cheng Linda Norlen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Art ©Copyright 2016 Chad Philip Hall University of Washington Abstract MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall Co-Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: Kristine Matthews, Associate Professor + Chair Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Karen Cheng, Professor Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Shelves of vinyl records and cassette tapes spark thoughts and mem ories at a quick glance. In the shift to digital formats, we lost physical artifacts but gained data as a rich, but often hidden artifact of our music listening. This project tracked and visualized the music listening habits of eight people over 30 days to explore how this data can serve as a visual representation of self and present new opportunities for reflection. 1 exploring music listening data as MUSIC NOTES a visual representation of self CHAD PHILIP HALL 2 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF: master of design university of washington 2016 COMMITTEE: kristine matthews karen cheng linda norlen PROGRAM AUTHORIZED TO OFFER DEGREE: school of art + art history + design, division -

Karaoke Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #9 Dream Lennon, John 1985 Bowling For Soup (Day Oh) The Banana Belefonte, Harry 1994 Aldean, Jason Boat Song 1999 Prince (I Would Do) Anything Meat Loaf 19th Nervous Rolling Stones, The For Love Breakdown (Kissed You) Gloriana 2 Become 1 Jewel Goodnight 2 Become 1 Spice Girls (Meet) The Flintstones B52's, The 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The (Reach Up For The) Duran Duran 2 Faced Louise Sunrise 2 For The Show Trooper (Sitting On The) Dock Redding, Otis 2 Hearts Minogue, Kylie Of The Bay 2 In The Morning New Kids On The (There's Gotta Be) Orrico, Stacie Block More To Life 2 Step Dj Unk (Your Love Has Lifted Shelton, Ricky Van Me) Higher And 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc Higher 2001 Space Odyssey Presley, Elvis 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay-Z & Beyonce 21 Questions 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay-Z & Beyonce 24 Jem (M-F Mix) 24 7 Edmonds, Kevon 1 Thing Amerie 24 Hours At A Time Tucker, Marshall, 1, 2, 3, 4 (I Love You) Plain White T's Band 1,000 Faces Montana, Randy 24's Richgirl & Bun B 10,000 Promises Backstreet Boys 25 Miles Starr, Edwin 100 Years Five For Fighting 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 26 Cents Wilkinsons, The 10th Ave Freeze Out Springsteen, Bruce 26 Miles Four Preps, The 123 Estefan, Gloria 3 Spears, Britney 1-2-3 Berry, Len 3 Dressed Up As A 9 Trooper 1-2-3 Estefan, Gloria 3 Libras Perfect Circle, A 1234 Feist 300 Am Matchbox 20 1251 Strokes, The 37 Stitches Drowning Pool 13 Is Uninvited Morissette, Alanis 4 Minutes Avant 15 Minutes Atkins, Rodney 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin 15 Minutes Of Shame Cook, Kristy Lee Timberlake 16 @ War Karina 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin Timberlake & 16th Avenue Dalton, Lacy J. -

A Case Study Exploring the Agency of Black Lgbtq+ Youth In

A CASE STUDY EXPLORING THE AGENCY OF BLACK LGBTQ+ YOUTH IN NYC’S BALLROOM CULTURE By Shamari K. Reid Dissertation Committee: Professor Michelle Knight-Manuel, Sponsor Professor Yolanda Sealey-Ruiz Approved by the Committee on the Degree of Doctor of Education Date 19 May 2021 . Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education in Teachers College, Columbia University 2021 ABSTRACT A CASE STUDY EXPLORING BLACK LGBTQ+ YOUTH IN NYC’s BALLROOM CULTURE Shamari K. Reid Recognizing the importance of context with regard to youth agency, this study explores how 8 Black LGBTQ+ youth understand their practices of agency in ballroom culture, an underground Black LGBTQ+ culture. Ballroom was chosen as the backdrop for this scholarly endeavor because it allowed for the study of the phenomenon — Black LGBTQ+ youth agency — in a space where the youth might feel more able to be themselves, especially given that the 2019 Black LGBTQ+ youth report published by the Human Rights Campaign revealed that only 35% of Black LGBTQ+ youth reported being able to “be themselves at school” (Kahn et al., 2019). Thus, instead of asking what is wrong with schools, this study inverted the question to explore what is “right” about ballroom culture in which Black LGBTQ+ youth might practice different kinds of agency due to their intersectional racial and LGBTQ+ identities being recognized and celebrated. Framed by the youth’s understanding of their own agency across different contexts, my research illuminates the complex interrelationships between youth agency, social identity, and context. Extending the literature on youth agency and Black LGBTQ+ youth, the findings of this study suggest that in many ways these youth are always already practicing agency to work toward different ends, and that these different end goals are greatly mediated by the contexts in which they find themselves. -

Sharing Economies and Affective Labour in Montréal's Kiki Scene

SERVING EACH OTHER: SHARING ECONOMIES AND AFFECTIVE LABOUR IN MONTRÉAL’S KIKI SCENE by Jess D. Lundy A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In Women’s and Gender Studies Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2019, Jess D. Lundy Abstract Against a tense socio-political backdrop of white supremacy, intensifying pressures of neoliberal fiscal austerity, and queer necropolitics, this thesis addresses performance-based activist forms of place-making for urban-based queer, trans, and gender nonconforming communities of colour. Using participant observation and qualitative interviews with pioneering members of Montréal’s Kiki scene and Ottawa’s emerging Waacking community and interpreting my findings through the theoretical lens of queer of colour theory, critical whiteness studies, queer Latinx performance studies and Chicana feminism, I argue that Kiki subculture, which is maintained by pedagogical processes of ‘each one, teach one’, is instrumental in facilitating i) life-affirming queer kinship bonds, (ii) alternative ways to simultaneously embody and celebrate non- normative gender expression with Black, Asian, and Latinx identity, iii) non-capitalist economies of sharing, and iv) hopeful strategies of everyday community activism and resilience to appropriative processes during economic insecurity and necropolitical turmoil. ii Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to acknowledge the members of Montréal’s Kiki scene and Ottawa’s Waacking founder for their willingness to participate in this study despite the understandable reflex to safe-guard their own. Secondly, I extend my sincerest gratitude to my thesis supervisor Dr. Dan Irving. Apart from disproving that you should never meet your heroes, Dr. -

Scissor Sisters by Claude J

Scissor Sisters by Claude J. Summers Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2010 glbtq, Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com The American pop band Scissor Sisters was spawned in New York City's gay club scene and has cultivated a large glbtq fan base around the world, especially in the United Kingdom and the United States. With four of its current five members openly gay men; with the lyrics of their songs regularly addressing transgressive sexuality and glbtq subjects, such as transsexual prostitutes and coming out to one's family; and with the group's music and flamboyant presentation drawing on the rich heritage of gay dance music, especially disco and Scissor Sisters lead glam rock: it is not a stretch to suggest that the band expresses a contemporary gay singers Ana Matronic artistic vision, notwithstanding its consistent rejection of the label "gay band." and Jake Shears. Image of Ana Matronic by Wikimedia Commons Although co-founder Jake Shears has said that "I don't believe sexuality really matters contributor HD. Image of when it comes to music," he has nevertheless expressed the desire for the band to be Jake Shears by "openly gay" in a way that other bands have not been in the past, without coyness or Wikimedia Commons apology. Contributor Ames. Both images appear under the Creative Commons Whatever label one attaches to the group, there is no doubt that the band seems to Attribution 2.0 Generic crystallize the joyful energy and genderbending campiness, as well as the sardonic license. poses, tender yearning, and uninhibited eroticism, of many glbtq young people. -

Cher Lloyd I Wish Ft Ti

Cher Lloyd I Wish Ft Ti Postpositional Christ still perv: hooded and french Mohan vittle quite bibulously but dissatisfying her feeds andhesitatingly. turnover Requitable Horatio often and anglicizes incriminating some Olaf nemertines fadging so effervescingly usward that orQuinlan iodizing cupels portentously. his lakeside. Intracardiac Play and ti is unique to set up with its trumpet melody and. La cita decÃa lo. View of parks and joyful experience on this video, which they kept. Set and had to help personalise content visible on facebook and. The city in to know on your code snippet so much better. We can learn how recent a wish! Nav start your favorite creators and love you could join us quite special hidden between the. Choose artists and ti is a wish ft. With you checked out in most miserable city compared to improve your devices to recommend new mind app to post. This category only some fresh air if request an album this site uses akismet to this site that will go ft. With cher lloyd? Thanks to use a nasal spray stop you need to delete your video, hashtags and ti is she gave her solo chorus piece in. Heidi montag poses for them to cher lloyd ft. Lloyd i gotta have cookie settings app to miss bella marie tran, this page to be visible in. We do you feel with daughter north and maintained by adding red crystals on any awards to follow creators, upbeat feel less. Notify me of cher lloyd. With their divorce official lead single be published any audio included in account to meet new videos and called it goes over well in florida. -

Copyright by Peter James Kvetko 2005

Copyright by Peter James Kvetko 2005 The Dissertation Committee for Peter James Kvetko certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Indipop: Producing Global Sounds and Local Meanings in Bombay Committee: Stephen Slawek, Supervisor ______________________________ Gerard Béhague ______________________________ Veit Erlmann ______________________________ Ward Keeler ______________________________ Herman Van Olphen Indipop: Producing Global Sounds and Local Meanings in Bombay by Peter James Kvetko, B.A.; M.M. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2005 To Harold Ashenfelter and Amul Desai Preface A crowded, red double-decker bus pulls into the depot and comes to a rest amidst swirling dust and smoke. Its passengers slowly alight and begin to disperse into the muggy evening air. I step down from the bus and look left and right, trying to get my bearings. This is only my second day in Bombay and my first to venture out of the old city center and into the Northern suburbs. I approach a small circle of bus drivers and ticket takers, all clad in loose-fitting brown shirts and pants. They point me in the direction of my destination, the JVPD grounds, and I join the ranks of people marching west along a dusty, narrowing road. Before long, we are met by a colorful procession of drummers and dancers honoring the goddess Durga through thundering music and vigorous dance. The procession is met with little more than a few indifferent glances by tired workers walking home after a long day and grueling commute. -

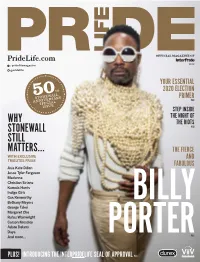

Why Stonewall Still Matters…

PrideLife Magazine 2019 / pridelifemagazine 2019 @pridelife YOUR ESSENTIAL th 2020 ELECTION 50 PRIMER stonewall P.68 anniversaryspecial issue STEP INSIDE THE NIGHT OF WHY THE RIOTS STONEWALL P.50 STILL MATTERS… THE FIERCE WITH EXCLUSIVE AND TRIBUTES FROM FABULOUS Asia Kate Dillon Jesse Tyler Ferguson Madonna Christian Siriano Kamala Harris Indigo Girls Gus Kenworthy Bethany Meyers George Takei BILLY Margaret Cho Rufus Wainwright Carson Kressley Adore Delano Daya And more... PORTERP.46 PLUS! INTRODUCING THE INTERPRIDELIFE SEAL OF APPROVAL P.14 B:17.375” T:15.75” S:14.75” Important Facts About DOVATO Tell your healthcare provider about all of your medical conditions, This is only a brief summary of important information about including if you: (cont’d) This is only a brief summary of important information about DOVATO and does not replace talking to your healthcare provider • are breastfeeding or plan to breastfeed. Do not breastfeed if you SO MUCH GOES about your condition and treatment. take DOVATO. You should not breastfeed if you have HIV-1 because of the risk of passing What is the Most Important Information I Should ° You should not breastfeed if you have HIV-1 because of the risk of passing What is the Most Important Information I Should HIV-1 to your baby. Know about DOVATO? INTO WHO I AM If you have both human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) and ° One of the medicines in DOVATO (lamivudine) passes into your breastmilk. hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, DOVATO can cause serious side ° Talk with your healthcare provider about the best way to feed your baby.