American Folklife Center News (Summer 2006)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015 23Rd Annual Poets House Showcase Exhibition Catalog

2015 23rd Annual Poets House Showcase Exhibition Catalog |Poets House|10 River Terrace|New York, NY 10282|poetshouse.org| 5 The 2015 Poets House Showcase is made possible through the generosity of the hundreds of publishers and authors who have graciously donated their works. We are deeply grateful to Deborah Saltonstall Pease (1943 – 2014) for her foundational support. Many thanks are also due to the National Endowment for the Arts, the New York State Council on the Arts, the NYC Department of Cultural Affairs, the Leon Levy Foundation, and the many members of Poets House for their support of this project. 6 I believe that poetry is an action in which there enter as equal partners solitude and solidarity, emotion and action, the nearness to oneself, the nearness to mankind and to the secret manifestations of nature. – Pablo Neruda Towards the Splendid City Nobel Lecture, 1971 WELCOME to the 2015 Poets House Showcase! Each summer at Poets House, we celebrate all of the poetry published in the previous year in an all-inclusive exhibition and festival of readings from new work. In this year’s Showcase, we are very proud to present over 3,000 poetry books, chapbooks, broadsides, artist’s books, and multimedia projects, which represent the work of over 700 publishers, from commercial publishers to micropresses, both domestic and foreign. For twenty-three years, the annual Showcase has provided foundational support for our 60,000-volume library by helping us keep our collection current and relevant. With each Showcase, Poets House—one of the most extensive poetry collections in the nation—continues to build this comprehensive poetry record of our time. -

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data As a Visual Representation of Self

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Design University of Washington 2016 Committee: Kristine Matthews Karen Cheng Linda Norlen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Art ©Copyright 2016 Chad Philip Hall University of Washington Abstract MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall Co-Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: Kristine Matthews, Associate Professor + Chair Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Karen Cheng, Professor Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Shelves of vinyl records and cassette tapes spark thoughts and mem ories at a quick glance. In the shift to digital formats, we lost physical artifacts but gained data as a rich, but often hidden artifact of our music listening. This project tracked and visualized the music listening habits of eight people over 30 days to explore how this data can serve as a visual representation of self and present new opportunities for reflection. 1 exploring music listening data as MUSIC NOTES a visual representation of self CHAD PHILIP HALL 2 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF: master of design university of washington 2016 COMMITTEE: kristine matthews karen cheng linda norlen PROGRAM AUTHORIZED TO OFFER DEGREE: school of art + art history + design, division -

Karaoke Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #9 Dream Lennon, John 1985 Bowling For Soup (Day Oh) The Banana Belefonte, Harry 1994 Aldean, Jason Boat Song 1999 Prince (I Would Do) Anything Meat Loaf 19th Nervous Rolling Stones, The For Love Breakdown (Kissed You) Gloriana 2 Become 1 Jewel Goodnight 2 Become 1 Spice Girls (Meet) The Flintstones B52's, The 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The (Reach Up For The) Duran Duran 2 Faced Louise Sunrise 2 For The Show Trooper (Sitting On The) Dock Redding, Otis 2 Hearts Minogue, Kylie Of The Bay 2 In The Morning New Kids On The (There's Gotta Be) Orrico, Stacie Block More To Life 2 Step Dj Unk (Your Love Has Lifted Shelton, Ricky Van Me) Higher And 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc Higher 2001 Space Odyssey Presley, Elvis 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay-Z & Beyonce 21 Questions 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay-Z & Beyonce 24 Jem (M-F Mix) 24 7 Edmonds, Kevon 1 Thing Amerie 24 Hours At A Time Tucker, Marshall, 1, 2, 3, 4 (I Love You) Plain White T's Band 1,000 Faces Montana, Randy 24's Richgirl & Bun B 10,000 Promises Backstreet Boys 25 Miles Starr, Edwin 100 Years Five For Fighting 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 26 Cents Wilkinsons, The 10th Ave Freeze Out Springsteen, Bruce 26 Miles Four Preps, The 123 Estefan, Gloria 3 Spears, Britney 1-2-3 Berry, Len 3 Dressed Up As A 9 Trooper 1-2-3 Estefan, Gloria 3 Libras Perfect Circle, A 1234 Feist 300 Am Matchbox 20 1251 Strokes, The 37 Stitches Drowning Pool 13 Is Uninvited Morissette, Alanis 4 Minutes Avant 15 Minutes Atkins, Rodney 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin 15 Minutes Of Shame Cook, Kristy Lee Timberlake 16 @ War Karina 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin Timberlake & 16th Avenue Dalton, Lacy J. -

NATIONAL COWBOY POETRY GATHERING January 27–February 1, 2020 · Elko, Nevada

Ocial Program , 2013 Trail Blazers Trail Marion Coleman, THE WESTERN FOLKLIFE CENTER presents THE 36TH NATIONAL COWBOY POETRY GATHERING January 27–February 1, 2020 · Elko, Nevada 36TH NATIONAL COWBOY POETRY GATHERING 1 Hear something thoughtful or get some inspiration? Write it down! Meet someone cool? Get their autograph! Donors, Sponsors, and Partners Thank You to Our Major Sponsors » The Ford Foundation » McMullen, McPhee & Co. LLC » William Randolph Hearst Foundation » John Muraglia » E. L. Wiegand Foundation » Jesselie & Scott Anderson » Elko Recreation Board » Reed & Mary Simmons » City of Elko » Sally Searle » NV Energy » Blach Distributing » Nevada Gold Mines » Elko Convention and Visitors Authority » Laura & E.W. Littlefield, Jr. » Red Lion Hotel & Casino » Nevada Arts Council » Stockmen’s Casino & Ramada Hotel » National Endowment for the Arts » Joel & Kim Laub $10,000 and up as of 12/16/19 Thank You to Our National Cowboy Poetry Gathering Sponsors and Partners » Nevada Humanities/National » C-A-L Ranch Endowment for the Humanities » Marigold Mine » Tito & Sandra Tiberti » Coach USA » The Martin Guitar Charitable Foundation » Townplace Suites by Marriott » Anna Ball » Morgan Stanley » KNPB Channel 5 Public Broadcasting » Picture This » Nevada Division of Tourism/TravelNevada » Wrangler » Best Western Elko Inn » Star Hotel » Ledgestone Hotel » Nevada Health Centers » Home2Home » Northeastern Nevada Regional Hospital » Wingate by Wyndham Elko » Great Basin Beverage » Holiday Inn & Suites » Northeastern Nevada Stewardship Group -

ED439719.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 439 719 IR 057 813 AUTHOR McCleary, Linda C., Ed. TITLE Read from Sea to Shining Sea. Arizona Reading Program. Program Manual. INSTITUTION Arizona Humanities Council, Phoenix.; Arizona State Dept. of Library, Archives and Public Records, Phoenix. PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 414p. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC17 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Cooperative Programs; Games; Learning Activities; *Library Planning; Library Services; *Reading Motivation; *Reading Programs; State Programs; Youth Programs IDENTIFIERS *Arizona ABSTRACT This year is the first for the collaborative effort between the Arizona Department of Library, Archives and Public Records, and Arizona Humanities Council and the members of the Arizona Reads Committee. This Arizona Reading Program manual contains information on program planning and development, along with crafts, activity sheets, fingerplays, songs, games and puzzles, and bibliographies grouped in age specific sections for preschool children through young adults, including a section for those with special needs. The manual is divided into the following sections: Introductory Materials; Goals, Objectives and Evaluation; Getting Started; Common Program Structures; Planning Timeline; Publicity and Promotion; Awards and Incentives; Parents/Family Involvement; Programs for Preschoolers; Programs for School Age Children; Programs for Young Adults; Special Needs; Selected Bibliography; Resources; Resource People; and Miscellaneous materials.(AEF) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. rn C21 Read from Sea to Shining Sea Arizona Reading Program Program Manual By Linda C. McCleary, Ed. U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND Office of Educational Research and Improvement DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIAL HAS EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION BEEN GRANTED BY CENTER (ERIC) This document has been reproduced as received from the person or organization Ann-Mary Johnson originating it. -

06 21 2016 (Pdf)

6-21-16 sect. 1.qxp:Layout 1 6/16/16 11:56 AM Page 1 Grandin emphasizes stockmanship at 5th International Symposium on Beef Cattle Welfare By Donna Sullivan, Editor and they all had the lower worse.” The one message that Dr. hair whorls. Cattle overall Grandin emphasized that Temple Grandin has champi- are getting calmer.” an animal’s first experience oned throughout her career is But she cautioned against with a new person, place or that stockmanship matters. over-emphasizing tempera- piece of equipment needs to And the world-renowned ment. “We don’t want to turn be a good one. “New things Colorado State University beef cattle into a bunch of are scary when you shove professor and livestock han- Holsteins,” she warned. them in their face,” she said. dling expert didn’t vary from “That would probably be a “But they are attractive when that theme as she presented really bad idea because we they voluntarily approach. A at the 5th International Sym- want a cow that’s going to basic principle is that when posium on Beef Cattle Wel- defend her calf.” you force animals to do fare hosted by Kansas State She also pointed out that something, you’re going to University’s Beef Cattle In- temperament scores can be get a lot more fear stress than stitute in early June. She pre- changed with experience, by when they voluntarily go sented a great deal of re- acclimating cattle to new through the facility.” search illustrating the corre- people and experiences. Un- Grandin said she has seen lation between how cattle are fortunately, people don’t al- an improvement in people’s handled and their overall ways want to take the time attitudes towards animals performance. -

American Folklife Center & Veterans History Project

AMERICAN FOLKLIFE CENTER & VETERANS HISTORY PROJECT Library of Congress Annual Report, Fiscal Year 2010 (October 2009-September 2010) The American Folklife Center (AFC), which includes the Veterans History Project (VHP), had another productive year. Over 150,000 items were acquired, and over 127,000 items were processed by AFC's archive, which is the country’s first national archive of traditional culture, and one of the oldest and largest of such repositories in the world. VHP continued making strides in its mission to collect and preserve the stories of our nation's veterans, acquiring 7,408 collections (13,744 items) in FY2010. The VHP public database provided access to information on all processed collections; its fully digitized collections, whose materials are available through the Library’s web site to any computer with internet access, now number over 8,000. Together, AFC and VHP acquired a total of 168,198 items in FY2010, of which 151,230 were Non-Purchase Items by Gift. AFC and VHP processed a total of 279,298 items in FY2010, and cataloged 54,758 items. AFC and VHP attracted just under five million “Page Views” on the Library of Congress website, not counting AFC’s popular “American Memory” collections. ARCHIVAL ACCOMPLISHMENTS KEY ACQUISITIONS American Voices with Senator Bill Bradley (AFC 2010/004) 117 born-digital audio recordings of interviews from the radio show American Voices, hosted by Sen. Bill Bradley (also appearing under the title American Voices with Senator Bill Bradley), produced by Devorah Klahr for Sirius XM Satellite Radio, Washington, D.C. Dyann Arthur and Rick Arthur Collection of MusicBox Project Materials (AFC 2010/029) Over 100 hours of audio and video interviews of women working as roots musicians and/or singers. -

Shorty's Yarns: Western Stories and Poems of Bruce Kiskaddon

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2004 Shorty's Yarns: Western Stories and Poems of Bruce Kiskaddon Bruce Kiskaddon Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the Folklore Commons Recommended Citation Kiskaddon, B., Field, K., & Siems, B. (2004). Shorty's yarns: Western stories and poems of Bruce Kiskaddon. Logan: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SHORTY’S YARNS Western Stories and Poems of Bruce Kiskaddon Illustrations by Katherine Field Edited and with an introduction by Bill Siems Shorty’s Yarns THE LONG HORN SPEAKS The old long horn looked at the prize winning steer And grumbled, “What sort of a thing is this here? He ain’t got no laigs and his body is big, I sort of suspicion he’s crossed with a pig. Now, me! I can run, I can gore, I can kick, But that feller’s too clumsy for all them tricks. They’re breedin’ sech critters and callin’ ‘em Steers! Why the horns that he’s got ain’t as long as my ears. I cain’t figger what he’d have done in my day. They wouldn’t have stuffed me with grain and with hay; Nor have polished my horns and have fixed up my hoofs, And slept me on beddin’ in under the roofs Who’d have curried his hide and have fuzzed up his tail? Not none of them riders that drove the long trail. -

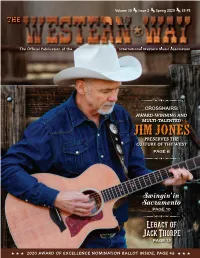

Spring 2020 $5.95 THE

Volume 30 Issue 2 Spring 2020 $5.95 THE The Offi cial Publication of the International Western Music Association CROSSHAIRS: AWARD-WINNING AND MULTI-TALENTED JIM JONES PRESERVES THE CULTURE OF THE WEST PAGE 6 Swingin’ in Sacramento PAGE 10 Legacy of Jack Thorpe PAGE 12 ★ ★ ★ 2020 AWARD OF EXCELLENCE NOMINATION BALLOT INSIDE, PAGE 46 ★ ★ ★ __WW Spring 2020_Cover.indd 1 3/18/20 7:32 PM __WW Spring 2020_Cover.indd 2 3/18/20 7:32 PM 2019 Instrumentalist of the Year Thank you IWMA for your love & support of my music! HaileySandoz.com 2020 WESTERN WRITERS OF AMERICA CONVENTION June 17-20, 2020 Rushmore Plaza Holiday Inn Rapid City, SD Tour to Spearfish and Deadwood PROGRAMMING ON LAKOTA CULTURE FEATURED SPEAKER Virginia Driving Hawk Sneve SESSIONS ON: Marketing, Editors and Agents, Fiction, Nonfiction, Old West Legends, Woman Suffrage and more. Visit www.westernwriters.org or contact wwa.moulton@gmail. for more info __WW Spring 2020_Interior.indd 1 3/18/20 7:26 PM FOUNDER Bill Wiley From The President... OFFICERS Robert Lorbeer, President Jerry Hall, Executive V.P. Robert’s Marvin O’Dell, V.P. Belinda Gail, Secretary Diana Raven, Treasurer Ramblings EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Marsha Short IWMA Board of Directors, herein after BOD, BOARD OF DIRECTORS meets several times each year; our Bylaws specify Richard Dollarhide that the BOD has to meet face to face for not less Juni Fisher Belinda Gail than 3 meetings each year. Jerry Hall The first meeting is usually in the late January/ Robert Lorbeer early February time frame, and this year we met Marvin O’Dell Robert Lorbeer Theresa O’Dell on February 4 and 5 in Sierra Vista, AZ. -

Whither Cowboy Poetry?

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for 1999 WHITHER COWBOY POETRY? Jim Hoy Emporia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Hoy, Jim, "WHITHER COWBOY POETRY?" (1999). Great Plains Quarterly. 902. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/902 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. WHITHER COWBOY POETRY? JIM HOY As a cultural phenomenon the explosion in high-heeled boots, silk neckerchief, leather popularity of cowboy poetry in the past dozen chaps-has long since become an icon that years has been nothing short of spectacular. represents the very nation: wear a cowboy hat Until the first full-scale cowboy poetry gath and you will be taken for an American any ering at Elko, Nevada, in late January 1985, where in the world. The two essential working poetry was arguably the one aspect of cowboy skills of the cowboy-roping cattle and riding culture that had not been expropriated into bucking horses-long ago have been trans American popular culture. Certainly the men formed from actual ranch work into one of the tal picture of the cowboy himself-big hat, nation's largest spectator and participant sports: rodeo. And the idealized, romanticized image of the cowboy (certainly far removed from the low-paid, hard-working hired man on horseback who actually works with cows, horses, and four-wheel-drive pickups) has be come, through pulp fiction, television, and James F. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Versions Title Artist Versions #1 Crush Garbage SC 1999 Prince PI SC #Selfie Chainsmokers SS 2 Become 1 Spice Girls DK MM SC (Can't Stop) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue SF 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue MR (Don't Take Her) She's All I Tracy Byrd MM 2 Minutes To Midnight Iron Maiden SF Got 2 Stars Camp Rock DI (I Don't Know Why) But I Clarence Frogman Henry MM 2 Step DJ Unk PH Do 2000 Miles Pretenders, The ZO (I'll Never Be) Maria Sandra SF 21 Guns Green Day QH SF Magdalena 21 Questions (Feat. Nate 50 Cent SC (Take Me Home) Country Toots & The Maytals SC Dogg) Roads 21st Century Breakdown Green Day MR SF (This Ain't) No Thinkin' Trace Adkins MM Thing 21st Century Christmas Cliff Richard MR + 1 Martin Solveig SF 21st Century Girl Willow Smith SF '03 Bonnie & Clyde (Feat. Jay-Z SC 22 Lily Allen SF Beyonce) Taylor Swift MR SF ZP 1, 2 Step Ciara BH SC SF SI 23 (Feat. Miley Cyrus, Wiz Mike Will Made-It PH SP Khalifa And Juicy J) 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind SC 24 Hours At A Time Marshall Tucker Band SG 10 Million People Example SF 24 Hours From Tulsa Gene Pitney MM 10 Minutes Until The Utilities UT 24-7 Kevon Edmonds SC Karaoke Starts (5 Min 24K Magic Bruno Mars MR SF Track) 24's Richgirl & Bun B PH 10 Seconds Jazmine Sullivan PH 25 Miles Edwin Starr SC 10,000 Promises Backstreet Boys BS 25 Minutes To Go Johnny Cash SF 100 Percent Cowboy Jason Meadows PH 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago BS PI SC 100 Years Five For Fighting SC 26 Cents Wilkinsons, The MM SC SF 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris SC 26 Miles Four Preps, The SA 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters PI SC 29 Nights Danni Leigh SC 10000 Nights Alphabeat MR SF 29 Palms Robert Plant SC SF 10th Avenue Freeze Out Bruce Springsteen SG 3 Britney Spears CB MR PH 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan BS SC QH SF Len Barry DK 3 AM Matchbox 20 MM SC 1-2-3 Redlight 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Karaoke Song Book Karaoke Nights Frankfurt’S #1 Karaoke

KARAOKE SONG BOOK KARAOKE NIGHTS FRANKFURT’S #1 KARAOKE SONGS BY TITLE THERE’S NO PARTY LIKE AN WAXY’S PARTY! Want to sing? Simply find a song and give it to our DJ or host! If the song isn’t in the book, just ask we may have it! We do get busy, so we may only be able to take 1 song! Sing, dance and be merry, but please take care of your belongings! Are you celebrating something? Let us know! Enjoying the party? Fancy trying out hosting or KJ (karaoke jockey)? Then speak to a member of our karaoke team. Most importantly grab a drink, be yourself and have fun! Contact [email protected] for any other information... YYOUOU AARERE THETHE GINGIN TOTO MY MY TONICTONIC A I L C S E P - S F - I S S H B I & R C - H S I P D S A - L B IRISH PUB A U - S R G E R S o'reilly's Englische Titel / English Songs 10CC 30H!3 & Ke$ha A Perfect Circle Donna Blah Blah Blah A Stranger Dreadlock Holiday My First Kiss Pet I'm Mandy 311 The Noose I'm Not In Love Beyond The Gray Sky A Tribe Called Quest Rubber Bullets 3Oh!3 & Katy Perry Can I Kick It Things We Do For Love Starstrukk A1 Wall Street Shuffle 3OH!3 & Ke$ha Caught In Middle 1910 Fruitgum Factory My First Kiss Caught In The Middle Simon Says 3T Everytime 1975 Anything Like A Rose Girls 4 Non Blondes Make It Good Robbers What's Up No More Sex....