2017) Unilag Law Review 1(2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BOKO HARAM Emerging Threat to the U.S

112TH CONGRESS COMMITTEE " COMMITTEE PRINT ! 1st Session PRINT 112–B BOKO HARAM Emerging Threat to the U.S. Homeland SUBCOMMITTEE ON COUNTERTERRORISM AND INTELLIGENCE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES December 2011 FIRST SESSION U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 71–725 PDF WASHINGTON : 2011 COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY PETER T. KING, New York, Chairman LAMAR SMITH, Texas BENNIE G. THOMPSON, Mississippi DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California LORETTA SANCHEZ, California MIKE ROGERS, Alabama SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas HENRY CUELLAR, Texas GUS M. BILIRAKIS, Florida YVETTE D. CLARKE, New York PAUL C. BROUN, Georgia LAURA RICHARDSON, California CANDICE S. MILLER, Michigan DANNY K. DAVIS, Illinois TIM WALBERG, Michigan BRIAN HIGGINS, New York CHIP CRAVAACK, Minnesota JACKIE SPEIER, California JOE WALSH, Illinois CEDRIC L. RICHMOND, Louisiana PATRICK MEEHAN, Pennsylvania HANSEN CLARKE, Michigan BEN QUAYLE, Arizona WILLIAM R. KEATING, Massachusetts SCOTT RIGELL, Virginia KATHLEEN C. HOCHUL, New York BILLY LONG, Missouri VACANCY JEFF DUNCAN, South Carolina TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania BLAKE FARENTHOLD, Texas MO BROOKS, Alabama MICHAEL J. RUSSELL, Staff Director & Chief Counsel KERRY ANN WATKINS, Senior Policy Director MICHAEL S. TWINCHEK, Chief Clerk I. LANIER AVANT, Minority Staff Director (II) C O N T E N T S BOKO HARAM EMERGING THREAT TO THE U.S. HOMELAND I. Introduction .......................................................................................................... 1 II. Findings .............................................................................................................. -

“Political Shari'a”? Human Rights and Islamic Law in Northern Nigeria

Human Rights Watch September 2004 Vol. 16, No. 9 (A) “Political Shari’a”? Human Rights and Islamic Law in Northern Nigeria I. Summary ..................................................................................................................................... 1 II. Recommendations ................................................................................................................... 6 To Nigerian government and judicial authorities, at federal and state levels ............... 6 To foreign governments and intergovernmental organizations...................................... 8 III. Background ............................................................................................................................. 9 Shari’a.....................................................................................................................................10 IV. The extension of Shari’a to criminal law in Nigeria........................................................13 Shari’a courts and appeal procedures................................................................................18 The role of the “ulama” ......................................................................................................19 Choice of courts...................................................................................................................19 V. Human rights violations under Shari’a in northern Nigeria............................................21 Use of the death penalty .....................................................................................................21 -

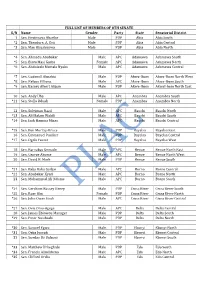

PROVISIONAL LIST.Pdf

S/N NAME YEAR OF CALL BRANCH PHONE NO EMAIL 1 JONATHAN FELIX ABA 2 SYLVESTER C. IFEAKOR ABA 3 NSIKAK UTANG IJIOMA ABA 4 ORAKWE OBIANUJU IFEYINWA ABA 5 OGUNJI CHIDOZIE KINGSLEY ABA 6 UCHENNA V. OBODOCHUKWU ABA 7 KEVIN CHUKWUDI NWUFO, SAN ABA 8 NWOGU IFIONU TAGBO ABA 9 ANIAWONWA NJIDEKA LINDA ABA 10 UKOH NDUDIM ISAAC ABA 11 EKENE RICHIE IREMEKA ABA 12 HIPPOLITUS U. UDENSI ABA 13 ABIGAIL C. AGBAI ABA 14 UKPAI OKORIE UKAIRO ABA 15 ONYINYECHI GIFT OGBODO ABA 16 EZINMA UKPAI UKAIRO ABA 17 GRACE UZOME UKEJE ABA 18 AJUGA JOHN ONWUKWE ABA 19 ONUCHUKWU CHARLES NSOBUNDU ABA 20 IREM ENYINNAYA OKERE ABA 21 ONYEKACHI OKWUOSA MUKOSOLU ABA 22 CHINYERE C. UMEOJIAKA ABA 23 OBIORA AKINWUMI OBIANWU, SAN ABA 24 NWAUGO VICTOR CHIMA ABA 25 NWABUIKWU K. MGBEMENA ABA 26 KANU FRANCIS ONYEBUCHI ABA 27 MARK ISRAEL CHIJIOKE ABA 28 EMEKA E. AGWULONU ABA 29 TREASURE E. N. UDO ABA 30 JULIET N. UDECHUKWU ABA 31 AWA CHUKWU IKECHUKWU ABA 32 CHIMUANYA V. OKWANDU ABA 33 CHIBUEZE OWUALAH ABA 34 AMANZE LINUS ALOMA ABA 35 CHINONSO ONONUJU ABA 36 MABEL OGONNAYA EZE ABA 37 BOB CHIEDOZIE OGU ABA 38 DANDY CHIMAOBI NWOKONNA ABA 39 JOHN IFEANYICHUKWU KALU ABA 40 UGOCHUKWU UKIWE ABA 41 FELIX EGBULE AGBARIRI, SAN ABA 42 OMENIHU CHINWEUBA ABA 43 IGNATIUS O. NWOKO ABA 44 ICHIE MATTHEW EKEOMA ABA 45 ICHIE CORDELIA CHINWENDU ABA 46 NNAMDI G. NWABEKE ABA 47 NNAOCHIE ADAOBI ANANSO ABA 48 OGOJIAKU RUFUS UMUNNA ABA 49 EPHRAIM CHINEDU DURU ABA 50 UGONWANYI S. AHAIWE ABA 51 EMMANUEL E. -

Boko Haram, Terrorism and Failing State Capacity in Nigeria: an Interrogation

BOKO HARAM, TERRORISM AND FAILING STATE CAPACITY IN NIGERIA: AN INTERROGATION DR. VICTOR EGWEMI KEY TERMS: Nigeria, Boko Haram, terrorism ABSTRACT: This paper is an interrogation of the activities of the Boko Haram sect especially since the killing of it leader Mohammed Yusuf under very controversial circumstances in 2009. It examines how the activities of Boko Haram have threatened the security and well-being of Nigerians and how it seems to have in turn undermined the Nigerian government’s ability to justify the reason for its existence, namely, to ensure the security and welfare of her citizens. Boko Haram has with seeming ease unleashed an orgy of violence characterized by bombing and killing Nigerians, especially in the north. This paper argues that sects like Boko Haram are a reaction to perceived and real injustices perpetrated by the state and its agencies. This paper is also of the opinion that the activities of Boko Haram have stretched Nigeria’s delicate socio-political and ethno-religious divides to the limit. The paper makes the point that a political solution, a well-meaning engagement between the government and the Boko Haram sect, is a more probable solution than the current attempt to engage the sect militarily. A political solution is not to be seen as a sign of weakness on the part of government but is, on the contrary, a sign of responsibility. The need to explore such a solution in the face of the crisis cannot be overemphasized. As a corollary, the government needs to tackle the crisis of infrastructure in the country. -

Twitter Ban and the Challenges of Digital Democracy in Africa

A PUBLICATION OF CISLAC @cislacnigeria www.facebook.com/cislacnigeria website: www.cislacnigeria.net VOL. 16 No. 5, MAY 2021 Participants in a group photo at a 'One-day CSO-Executive-Legislative Roundtable to appraise the Protection of Civilians and Civilian Harm mitigation in Armed Conflict' organised by CISLAC in collaboration with Centre for Civilians in Conflict with support from European Union. Twitter Ban And The Challenges Of Digital Democracy In Africa By Auwal Ibrahim Musa (Rafsanjani) America (VOA) observes that in ParliamentWatch in Uganda; and Uganda, the website Yogera, or ShineYourEye in Nigeria. s the emergence of digital 'speak out', offers a platform for The 2020 virtual protest in media shapes Africans' way citizens to scrutinize government, Z a m b i a t o Aof life, worldview, civic complain about poor service or blow #ZimbabweanLivesMatter, exposed mobilisation, jobs and opportunities, the whistle on corruption; Kenya's the potential of social media to public perception and opinion of Mzalendo website styles itself as the empower dissenting voices. The governance, the digital democracy 'Eye on the Kenyan Parliament', impact of WhatsApp and Facebook in also evolves in gathering pace for profiling politicians, scrutinizing Gambia's elections has indicated average citizens to take an active role expenses and highlighting citizens' that even in rural areas with limited in public discourse. rights; People's Assembly and its connectivity, social media content In 2017 published report, Voice of sister site PMG in South Africa; Cont. on page 4 Senate Passes Nigeria Still Southwest Speakers Want Procurement of Experts Review Draft Policy on Civilians’ University Bill Dromes, Helicopters to tackle Insecurity Protection in Harmed Conflict - P. -

How Senate, House of Reps Passed 2016 Budget - Premium Times Nigeria

How Senate, House of Reps passed 2016 budget - Premium Times Nigeria http://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/top-news/200742-senate-house... Opinion About Us Contact Us Careers AdvertRates PlayGames The sm arttrading app Startnow w itha free £10K D em o! Yourcapitalisatrisk. Thursday, May 19, 2016 Abuja 23 Home News #PanamaPapers Investigations Business Arts/Life Sports Oil/Gas Reports AGAHRIN Parliament Watch Letters How Senate, House of Reps passed 2016 budget March 24, 2016 Hassan Adebayo Search Our Stories The Nigerian Senate SHARING RELATED NEWS The two chambers of Nigeria’s National Assembly, the Senate and the House Finally, Senate, House of Representatives, on Wednesday passed the 2016 budget after the adoption of Reps receive 2016 of the conference report of their respective appropriations committees. Email budget report The National Assembly approved N6.06 trillion, a reduction on the 6.08 Print trillion proposed by President Muhammadu Buhari. National Assembly More fails to pass 2016 But the committees on appropriations of the Senate and the House chaired budget as promised by Danjuma Goje and Abdulmumin Jibrin, delivered damning remarks on the harmonized budget report presented to their separate chambers. Senate, House pledge 2016 budget passage in In the adopted report, the National Assembly observed the late presentation 2 weeks of the budget, saying it “was seen to be fraught with some inconsistencies from the MDAs; given subsequent reference by them to different versions of Saraki warns senators against taking bribes the budget”. for 2016 budget “This is strange and goes against proper budgetary procedures and processes; with attendant implications,” the report said. -

House of Reps Order Paper 7 July , 2020

FOURTH REPUBLIC 9TH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY (2019-2023) SECOND SESSION NO. 8 9 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA ORDER PAPER Tuesday, 7 July, 2020 1. Prayers 2. National Pledge 3. Approval of the Votes and Proceedings 4. Oaths 5. Messages from the President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (if any) 6. Messages from the Senate of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (if any) 7. Messages from Other Parliament(s) (if any) 8. Other Announcements (if any) 9. Petitions (if any) 10. Matters of Urgent Public Importance 11. Personal Explanation PRESENTATION OF BILLS 1. Federal Co-operative Colleges (Establishment) Bill, 2020 (HB. 913) (Hon. Gideon Gwani) – First Reading. 2. Family Support Trust Fund Act (Repeal) Bill, 2020 (HB. 914) (Hon. Gideon Gwani) – First Reading. 3. Nigerian Institute of Animal Science Act (Amendment) Bill, 2020 (HB. 915) (Hon. Gideon Gwani) – First Reading. 4. Orthopaedic Hospitals Management Board Act (Amendment) Bill, 2020 (HB. 916) (Hon. Gideon Gwani) – First Reading. 5. Tertiary Education Trust Fund (Establishment Etc.) Act (Amendment)) Bill, 2020 (HB.863) (Hon. Nkeiruka Onyejeocha) – First Reading. 6. National Security Investment Bill, 2020 (HB. 917) (Hon. Oluwole Oke) – First Reading. 10. Tuesday, 7 July, 2020 No. 8 7. Chartered Institute of Information and Strategy Management (Establishment etc.) Bill, 2020 (HB. 918) (Hon. Gideon Gwani) – First Reading. 8. Medical Negligence (Litigation) Bill, 2020 (HB. 919) (Hon. Oluwole Oke) – First Reading. 9. Limitation Periods (Freezing) Bill, 2020 (HB. 920) (Hon. Onofiok Luke) – First Reading. 10. National Water Resources Bill, 2020 (HB. 921) (Hon. Sada Soli Jiba) – First Reading. 11. Obafemi Awolowo University (Transitional Provisions) Act (Amendment) Bill, 2020 (HB.922) (Hon. -

Composition of Senate Committees Membership

LIST OF SPECIAL AND STANDING COMMITTEES OF THE 8TH ASSEMBLY-SENATE COMMITTEE ON AGRICULTURE AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT S/N NAMES MEMBERSHIP 1 Sen. Abdullahi Adamu Chairman 2 Sen. Theodore Orji Deputy Chairman 3 Sen. Shittu Muhammad Ubali Member 4 Sen. Adamu Muhammad Aliero Member 5 Sen. Abdullahi Aliyu Sabi Member 6 Sen. Bassey Albert Akpan Member 7 Sen. Yele Olatubosun Omogunwa Member 8 Sen. Emmanuel Bwacha Member 9 Sen. Joseph Gbolahan Dada Member COMMITTEE ON ARMY S/N NAMES MEMBERSHIP 1. Sen. George Akume Chairman 2 Sen. Ibrahim Danbaba Deputy Chairman 3 Sen. Binta Masi-Garba Member 4 Sen. Abubakar Kyari Member 5 Sen. Mohammed Sabo Member 6 Sen. Abdulrahman Abubakar Alhaji Member 7 Sen. Donald Omotayo Alasoadura Member 8 Sen. Lanre Tejuosho Adeyemi Member 9 Sen. James Manager Member 10 Sen. Joseph Obinna Ogba Member COMMITTEE ON AIRFORCE S/N NAMES MEMBERSHIP 1 Sen. Duro Samuel Faseyi Chairman 2 Sen. Ali Malam Wakili Deputy Chairman 3 Sen. Bala Ibn Na'allah Member 4 Sen. Bassey Albert Akpan Member 5 Sen. David Umaru Member 6 Sen. Oluremi Shade Tinubu Member 7 Sen. Theodore Orji Member 8 Sen. Jonah David Jang Member 9. Sen. Shuaibu Lau Member COMMITTEE ON ANTI-CORRUPTION AND FINANCIAL CRIMES S/N NAMES MEMBERSHIP 1 Sen. Chukwuka Utazi Chairman 2 Sen. Mustapha Sani Deputy Chairman 3 Sen. Mohammed Sabo Member 4 Sen. Bababjide Omoworare Member 5 Sen. Monsurat Sumonu Member 6 Sen. Isa Hamma Misau Member 7 Sen. Dino Melaye Member 8 Sen. Matthew Urhoghide Member COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS S/N NAMES MEMBERSHIP 1 Sen. Danjuma Goje Chairman 2 Sen. -

Full List of Members of the 8Th Senate

FULL LIST OF MEMBERS OF 8TH SENATE S/N Name Gender Party State Senatorial District 1 Sen. Enyinnaya Abaribe Male PDP Abia Abia South *2 Sen. Theodore. A. Orji Male PDP Abia Abia Central *3 Sen. Mao Ohuabunwa Male PDP Abia Abia North *4 Sen. Ahmadu Abubakar Male APC Adamawa Adamawa South *5 Sen. Binta Masi Garba Female APC Adamawa Adamawa North *6 Sen. Abdulaziz Murtala Nyako Male APC Adamawa Adamawa Central *7 Sen. Godswill Akpabio Male PDP Akwa-Ibom Akwa-Ibom North West *8 Sen. Nelson Effiong Male APC Akwa-Ibom Akwa-Ibom South *9 Sen. Bassey Albert Akpan Male PDP Akwa-Ibom AkwaI-bom North East 10 Sen. Andy Uba Male APC Anambra Anambra South *11 Sen. Stella Oduah Female PDP Anambra Anambra North 12 Sen. Suleiman Nazif Male APC Bauchi Bauchi North *13 Sen. Ali Malam Wakili Male APC Bauchi Bauchi South *14 Sen. Isah Hamma Misau Male APC Bauchi Bauchi Central *15 Sen. Ben Murray-Bruce Male PDP Bayelsa Bayelsa East 16 Sen. Emmanuel Paulker Male PDP Bayelsa Bayelsa Central *17 Sen. Ogola Foster Male PDP Bayelsa Bayelsa West 18 Sen. Barnabas Gemade Male APC Benue Benue North East 19 Sen. George Akume Male APC Benue Benue North West 20 Sen. David B. Mark Male PDP Benue Benue South *21 Sen. Baba Kaka Garbai Male APC Borno Borno Central *22 Sen. Abubakar Kyari Male APC Borno Borno North 23 Sen. Mohammed Ali Ndume Male APC Borno Borno South *24 Sen. Gershom Bassey Henry Male PDP Cross River Cross River South *25 Sen. Rose Oko Female PDP Cross River Cross River North *26 Sen. -

House of Representatives Federal Republic of Nigeria Order Paper

63 FOURTH REPUBLIC 9TH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY (2019 – 2023) FIRST SESSION NO. 16 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA ORDER PAPER Tuesday 23 July, 2019 1. Prayers 2. Approval of the Votes and Proceedings 3. Oaths 4. Message from the President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (if any) 5. Message from the Senate of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (if any) 6. Other Announcements (if any) 7. Petitions (if any) 8. Matter(s) of Urgent Public Importance 9. Personal Explanation _______________________________________________________ PRESENTATION OF BILLS 1. Asset Management Corporation of Nigeria Act (Amendment) Bill, 2019 (HB.203) (Hon. Nkeiruka Onyejeocha) – First Reading. 2. Nigerian Assets Management Agency (Establishment) Bill, 2019 (HB.204) (Hon. Nkeiruka Onyejeocha) – First Reading. 3. Securitization Bill, 2019 (HB.205) (Hon. Nkeiruka Onyejeocha) – First Reading. 4. Payment Systems Management Bill, 2019 (HB. 206) (Hon. Nkeiruka Onyejeocha) – First Reading. 5. Witness Protection Programme Bill, 2019 (HB. 207) (Hon. Nkeiruka Onyejeocha) – First Reading. 6. Pension Reform Act (Amendment) Bill, 2019 (HB.208) (Hon. Aishatu Jibril Dukku) – First Reading. 7. National Universities Commission Act (Amendment) Bill, 2019 (HB.209) (Hon. Aishatu Jibril Dukku) – First Reading. 64 Tuesday 23 July, 2019 No. 16 8. National Universities Commission Act (Amendment) Bill, 2019 (HB.209) (Hon. Aishatu Jibril Dukku) – First Reading. 9. Cerebrospinal Meningitis (Prevention, Control and Management) Bill, 2019 (HB.210) (Hon. Aishatu Jibril Dukku) – First Reading. 10. Companies and Allied Matters Act (Amendment) Bill, 2019 (HB.211) (Hon. Yusuf Buba Yakub) – First Reading. 11. Federal University, Oye Ekiti, Act (Amendment) Bill, 2019 (HB.212) (Hon. Adeyemi Adaramodu) – First Reading. 12. FCT Wider Area Planning and Development Commission Bill, 2019 (HB.213) (Hon. -

In Plateau and Kaduna States, Nigeria

HUMAN “Leave Everything to God” RIGHTS Accountability for Inter-Communal Violence WATCH in Plateau and Kaduna States, Nigeria “Leave Everything to God” Accountability for Inter-Communal Violence in Plateau and Kaduna States, Nigeria Copyright © 2013 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-0855 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org DECEMBER 2013 978-1-62313-0855 “Leave Everything to God” Accountability for Inter-Communal Violence in Plateau and Kaduna States, Nigeria Summary and Recommendations .................................................................................................... -

HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES FEDERAL REPUBLIC of NIGERIA ORDER PAPER Tuesday, 31 January, 2012

FOURTH REPUBLIC 7TH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY FIRST SESSION No. 109 351 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA ORDER PAPER Tuesday, 31 January, 2012 1. Prayers 2. Approval of the Votes and Proceedings 3. Oaths 4. Announcements (if any) S. Petitions (if any) 6. Matter(s) of Urgent Public Importance 7. Personal Explanation PRESENTATION OF BILLS 1. Police Ombudsman (Establishment) Bill, 2011 (HB. 92) (Hon. Ndudi Godwin Elumelu) - First Reading. 2. Nigerian Infrastructure Development Bank Bill, 2011 (HB. 108) (Hon. 1m Akpan Udoka) - First Reading. 3. Witness Protection Programme Bill, 2011 (HB. 118) (Hon. Nkeiruka Onyejeocha) - First Reading. 4. Senior Citizens Center Bill, 2011 (HB. 119) (Hon. Nkeiruka Onyejeocha) - First Reading. S. Anti-Torture Bill, 2011 (HB. 120) (Hon. Nkeiruka Onyejeocha) - First Reading. 6. Nigerian Sports Dispute Resolution Center Bill, 2011 (HB. 121) tHon. Robinson Uwak) - First Reading. 7. Constitutionof the Federal Republic of Nigeria (Further Alteration) Bill, 2011 (HB. 123) (Hon. Fon lJeanyi Dike) - First Reading. 8. National Socio-Cultural Integration Bill, 2011 (HB. 124) (Hon. Fort lJeanyi Dike) - First Reading. 9. Constitutionof the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 (Further Amendment) Bill, 2011 (HB. 151) (Hon. Leo Okuweh Ogor) - First Reading. PRJNTED BY NA TlONAL ASSEMBLY PRESS, ABUJA 352 Tuesday, 31 January. 2012 No. 109 PRESENTATION OF REPORTS 1. Committee of Federal Capital Territory: Hon. Emmanuel Jime: "That this House do receive the Report of the Committee on Federal Capital Territory on the Urgent Need to Construct Pedestrian Bridges along the Nnamdi Azikiwe By-Pass, Abuja" (HR. 83/2011) (Referred: 3011112011). 2. Committee of Federal Capital Territory: Hon. Emmanuel Jime: "That this House do receive the Report of the Committee on Federal Capital Territory Report on the Reactivation of the Abuja Rail Project" (HR.