Pittsburgh in the Great Epidemic Of1918

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pa-Railroad-Shops-Works.Pdf

[)-/ a special history study pennsylvania railroad shops and works altoona, pennsylvania f;/~: ltmen~on IndvJ·h·;4 I lferifa5e fJr4Je~i Pl.EASE RETURNTO: TECHNICAL INFORMATION CENTER DENVER SERVICE CE~TER NATIONAL PARK SERVICE ~ CROFIL -·::1 a special history study pennsylvania railroad shops and works altoona, pennsylvania by John C. Paige may 1989 AMERICA'S INDUSTRIAL HERITAGE PROJECT UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR I NATIONAL PARK SERVICE ~ CONTENTS Acknowledgements v Chapter 1 : History of the Altoona Railroad Shops 1. The Allegheny Mountains Prior to the Coming of the Pennsylvania Railroad 1 2. The Creation and Coming of the Pennsylvania Railroad 3 3. The Selection of the Townsite of Altoona 4 4. The First Pennsylvania Railroad Shops 5 5. The Development of the Altoona Railroad Shops Prior to the Civil War 7 6. The Impact of the Civil War on the Altoona Railroad Shops 9 7. The Altoona Railroad Shops After the Civil War 12 8. The Construction of the Juniata Shops 18 9. The Early 1900s and the Railroad Shops Expansion 22 1O. The Railroad Shops During and After World War I 24 11. The Impact of the Great Depression on the Railroad Shops 28 12. The Railroad Shops During World War II 33 13. Changes After World War II 35 14. The Elimination of the Older Railroad Shop Buildings in the 1960s and After 37 Chapter 2: The Products of the Altoona Railroad Shops 41 1. Railroad Cars and Iron Products from 1850 Until 1952 41 2. Locomotives from the 1860s Until the 1980s 52 3. Specialty Items 65 4. -

Gunstreamc 2015 Final.Pdf (1.383Mb)

Gunstream 1 Home Rule or Rome Rule? The Fight in Congress to Prohibit Funding for Indian Sectarian Schools and Its Effects on Montana Gunstream 2 Preface: During winter break of my sophomore and senior years I went on a headlights trip to Browning, MT with Carroll College Campus Ministry. We worked at a De La Salle Blackfeet School, a private catholic school that served kids from fourth through eighth grade. I was inspired by the work they were doing there and from my knowledge it was the only Catholic Indian school in Montana and this perplexed me—it was my knowledge that the original Catholic missions had schools on the reservations. In April of my sophomore year I went to Dr. Jeremy Johnson’s office to discuss writing an honors thesis on the relationship between the government and Indian reservation schools in Montana. He was very excited about the idea and told me to start reading up on the subject. I started reading on the history of the Catholic missions in Montana. I was interested by the stories of the nuns and priests who came a long ways to start these missions and serve the Native Americans. And I was interested in how prominent the Catholic Church was in the development of Montana. So I asked myself, what happened to them? The authors of the books answered this question only briefly: the federal government cut funding for these schools between 1896 and 1900, and the mission schools could barely survive without these funds. Eventually, some faster than others, they withered away. -

Herron Hill Pumping Station City of Pittsburgh Historic Landmark Nomination

Herron Hill Pumping Station City of Pittsburgh Historic Landmark Nomination Prepared by Preservation Pittsburgh 412.256.8755 1501 Reedsdale St., Suite 5003 October, 2019. Pittsburgh, PA 15233 www.preservationpgh.org HISTORIC REVIEW COMMISSION Division of Development Administration and Review City of Pittsburgh, Department of City Planning 200 Ross Street, Third Floor Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15219 INDIVIDUAL PROPERTY HISTORIC NOMINATION FORM Fee Schedule HRC Staff Use Only Please make check payable to Treasurer, City of Pittsburgh Date Received: .................................................. Individual Landmark Nomination: $100.00 Parcel No.: ........................................................ District Nomination: $250.00 Ward: ................................................................ Zoning Classification: ....................................... 1. HISTORIC NAME OF PROPERTY: Bldg. Inspector: ................................................. Council District: ................................................ Herron Hill Pumping Station (Pumping Station Building and Laboratory Building) 2. CURRENT NAME OF PROPERTY: Herron Hill Pumping Station 3. LOCATION a. Street: 4501 Centre Avenue b. City, State, Zip Code: Pittsburgh, PA 15213-1501 c. Neighborhood: North Oakland 4. OWNERSHIP d. Owner(s): City of Pittsburgh e. Street: City-County Building, 414 Grant Street f. City, State, Zip Code: Pittsburgh, PA 15219 Phone: ( ) - 5. CLASSIFICATION AND USE – Check all that apply Type Ownership Current Use: Structure Private – home Water -

Trailblazer-Jeff.Pdf

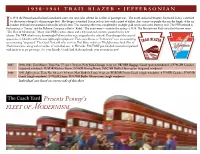

1938-1941 TRAIL BLAZER • JEFFERSONIAN n 1938 the Pennsylvania Railroad introduced a new two tone color scheme for it’s fleet of passenger cars. The noted industrial designer, Raymond Loewy is credited for the exterior design for the passenger fleet. His design of standard Tuscan red car sides with a panel of darker, almost maroon-purple that ran the length of the car window level and terminated in half circles at both ends. This stunning effect was completed by multiple gold stripes and a new lettering style. The PRR referred to Ithe lettering as “Futura” and the Pullman Company called it “Kabel.” The trains were to ready in the spring of 1938. The Pennsylvania Railroad called the new trains “The Fleet of Modernism.” Many older PRR coaches, diners and a few head end cars were painted in the new scheme. The PRR rebuilt some heavyweight Pullmans that were assigned to the railroad. They changed the external appearance to blend in with the new lightweight equipment. There were knowe as “betterment” cars, an accounting term meaning “improved.” The Coach Yard will offer an 8-car Trail Blazer and 8-car The Jeffersonian, both Fleet of Modernism trains, along with a number of individual cars, in HO scale, FACTORY pro-finished: lettered and painted Jeffersonian with interiors as per prototype. See your friendly Coach Yard dealer and make your reservations now! 1865 1938-1941 Trail Blazer, Train No. 77 east / 78 west, New York-Chicago 8 car set: PB70ER Baggage Coach (paired windows), 4 P70GSR Coaches (w/paired windows), D70DR Kitchen Dorm, D70CR Dining Room, POC70R Buffet Observation (w/paired windows) 1866 1941 Jeffersonian, Train No. -

PENNSYLVANIA, STATE of GEOR- GIA, STATE of MICHIGAN, and STATE of WISCONSIN, Defendants

No. 22O155 In the Supreme Court of the United States STATE OF TEXAS, Plaintiff v. COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA, STATE OF GEOR- GIA, STATE OF MICHIGAN, AND STATE OF WISCONSIN, Defendants ON MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BILL OF COMPLAINT OPPOSITION TO MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BILL OF COMPLAINT AND MOTION FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION, TEMPROARY RESTRAINING ORDER, OR STAY JOSH SHAPIRO Attorney General of Pennsylvania J. BART DELONE Chief Deputy Attorney General Appellate Litigation Section Counsel of Record HOWARD G. HOPKIRK CLAUDIA M. TESORO Office of Attorney General SEAN A. KIRKPATRICK 15th Floor Sr. Deputy Attorneys General Strawberry Square Harrisburg, PA 17120 MICHAEL J. SCARINCI (717) 712-3818 DANIEL B. MULLEN [email protected] Deputy Attorneys General TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PRELIMINARY STATEMENT ....................................1 STATEMENT OF THE CASE ......................................2 A. Mail-in Voting under the Pennsylvania Election Code ......................................................2 B. The 2020 General Election .................................3 C. Texas’s Allegations regarding Pennsylvania have Already Been Rejected by Both State and Federal Courts .............................................3 ARGUMENT .................................................................8 I. Texas’s Claims Do Not Meet the Exacting Standard Necessary for the Court to Exercise its Original Jurisdiction ...............................................8 II. Texas Does Not Present a Viable Case and Controversy ........................................................... -

Railroad History ‐ Specific to Pennsylvania Denotes That the Book Is Available from the Pennsylvania State Library, Harrisburg PA

Railroad History ‐ Specific to Pennsylvania denotes that the book is available from the Pennsylvania State Library, Harrisburg PA. Primary Resources Company History – Annual Reports Dredge, James. The Pennsylvania Railroad: Its Organization, Construction and Management. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1879. Pennsylvania, General Assembly. Charters and Acts of Assembly [Relating to the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad Company, Philadelphia & Reading Coal and Iron Company, other companies]. n.p., 1875. Pennsylvania, Office of the Auditor General. Annual Report of the Auditor General of the State of Pennsylvania and of the Tabulations and Deductions from the Reports of the Railroad and Canal Companies for the Years (1866‐1871, 1873‐1874). Harrisburg, PA: Singerly & Myers, State Printers, 1867‐1875. Pennsylvania, Office of the Auditor General. Reports of the Several Railroad Companies of Pennsylvania, Communicated by the Auditor General to the Legislature. Harrisburg, PA: Singerly & Meyers, State Printers, 1866. Pennsylvania Railroad. Annual Report of the Board of Directors to the Stockholders of the Pennsylvania Rail Road Company (1848, 1859, 1942). Philadelphia, PA: Pennsylvania Railroad Company. The Reading Railroad: The History of a Great Trunk Line. Philadelphia: Burk & McFetridge, printers, 1892. Report on the South Pennsylvania Railroad: Also, its Charters and Supplements. Harrisburg, PA: Sieg, 1869. Richardson, Richard. Memoir of Josiah White: Showing His Connection with the Introduction and Use of Anthracite Coal and Iron and the Construction of Some of the Canals and Railroads of Pennsylvania. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1873. Shamokin, Sunbury & Lewisburg Railroad. Approximate Estimates of Adopted Line…Through Sunbury, and Adverse and Level Line Through Same Place, July 28, 1882. [n.p.], 1882. -

Lawsuits, Thereby Weakening Ballot Integrity

No. ______, Original In the Supreme Court of the United States STATE OF TEXAS, Plaintiff, v. COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA, STATE OF GEORGIA, STATE OF MICHIGAN, AND STATE OF WISCONSIN, Defendants. MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BILL OF COMPLAINT Ken Paxton* Attorney General of Texas Brent Webster First Assistant Attorney General of Texas Lawrence Joseph Special Counsel to the Attorney General of Texas Office of the Attorney General P.O. Box 12548 (MC 059) Austin, TX 78711-2548 [email protected] (512) 936-1414 * Counsel of Record i TABLE OF CONTENTS Pages Motion for leave to File Bill of Complaint ................. 1 No. ______, Original In the Supreme Court of the United States STATE OF TEXAS, Plaintiff, v. COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA, STATE OF GEORGIA, STATE OF MICHIGAN, AND STATE OF WISCONSIN, Defendants. MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BILL OF COMPLAINT Pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1251(a) and this Court’s Rule 17, the State of Texas respectfully seeks leave to file the accompanying Bill of Complaint against the States of Georgia, Michigan, and Wisconsin and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (collectively, the “Defendant States”) challenging their administration of the 2020 presidential election. As set forth in the accompanying brief and complaint, the 2020 election suffered from significant and unconstitutional irregularities in the Defendant States: • Non-legislative actors’ purported amendments to States’ duly enacted election laws, in violation of the Electors Clause’s vesting State legislatures with plenary authority regarding the appointment of presidential electors. • Intrastate differences in the treatment of voters, with more favorable allotted to voters – whether lawful or unlawful – in areas administered by local government under Democrat control and with populations with higher ratios of Democrat voters than other areas of Defendant States. -

The Aerodynamic Effects of High-Speed Trains on People and Property at Stations in the Northeast Corridor RR0931R0061 6

THE AERODYNAMIC EFFECTS OF u. S. Department of Transportation HIGH-SPEED TRAINS ON PEOPLE Federal Railroad Administration AND PROPERTY AT STATIONS IN THE NORTHEAST CORRIDOR. PB2000-103859 III III[[11111[11111111111111111111 Safety of High-Speed Ground Transportation Systems REPRODUCED BY: N 'JS. u.s. Department of Commerce National Technical Information Service Springfield, Virginia 22161 NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. NOTICE The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers' names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the objective of this report. Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1hour per response, includi'iPe the time for reviewing instructions, searchin~ eXistin?< data sources,rnthering and maintaining the data needed and completin~ and reviewin~ the collection of information. Send comments r~arding this bur en estimate or an~ other aspect of this collec Ion of in ormation, inclu IOlb,SU8%estions for redUCin~ this bur~~~. l0 ~hirron eadquarters ilfrvices, D~~torate~g[c Information Operations an Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Ighway. Suite 1204, Mnglon, VA 22202-4302, and to e ice of Managemen and Bud et Pa rwo Reduction Project 0704-0188 Washin on DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED November 1999 Final Report January 1998 - January 1999 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. -

City of Pittsburgh, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania Planning Sector 4: West Pittsburgh West End & Elliott Neighborhoods Report of Findings and Recommendations

Architectural Inventory for the City of Pittsburgh, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania Planning Sector 4: West Pittsburgh West End & Elliott Neighborhoods Report of Findings and Recommendations The City of Pittsburgh In Cooperation With: Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission September 2018 Paving Chartiers Avenue in Elliott, April 28, 1910, view northwest from Lorenz Avenue. Pittsburgh City Photographer’s Collection, Archives of Industrial Society, University of Pittsburgh Prepared By: Michael Baker International, Inc. Jesse A. Belfast Justin Greenawalt and Clio Consulting Angelique Bamberg with Cosmos Technologies, Inc. James Brown The Architectural Inventory for the City of Pittsburgh, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, was made possible with funding provided by the Pennsylvania State Historic Preservation Office (PA SHPO), the City of Pittsburgh, and the U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Certified Local Government program. The contents and opinions contained in this document do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior. This program receives federal financial assistance for identification and protection of historic properties. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, as amended, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, disability, or age in its federally assisted programs. If you believe you have been discriminated against -

Improving Intercity Passenger Rail Service in the United States

Improving Intercity Passenger Rail Service in the United States Updated February 8, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45783 SUMMARY R45783 Improving Intercity Passenger Rail Service February 8, 2021 in the United States Ben Goldman The federal government has been involved in preserving and improving passenger rail service Analyst in Transportation since 1970, when the bankruptcies of several major railroads threatened the continuance of Policy passenger trains. Congress responded by creating Amtrak—officially, the National Railroad Passenger Corporation—to preserve a basic level of intercity passenger rail service, while relieving private railroad companies of the obligation to maintain a business that had lost money for decades. In the years since, the federal government has funded Amtrak and, in recent years, has funded passenger-rail efforts of varying size and complexity through grants, loans, and tax subsidies. Most recently, Congress has attempted to manage the effects on passenger rail brought about by the sudden drop in travel demand due to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Amtrak’s ridership and revenue growth trends were suddenly upended, and passenger rail service in many markets was either reduced or suspended. Efforts to improve intercity passenger rail can be broadly grouped into two categories: incremental improvement of existing services operated by Amtrak and implementation of new rail service where none currently exists. Efforts have been focused on identifying corridors where passenger rail travel times would be competitive with driving or flying (generally less than 500 miles long) and where population density and intercity travel demand create favorable conditions for rail service. -

The Physical and Cultural Development of Pittsburgh's Highland

1 Nathaniel Mark Johns Hopkins University Building a Community: The Physical and Cultural Development of Pittsburgh’s Highland Park Neighborhood, 1778-1900 INTRODUCTION The 22nd census (2000) showed for the first time that the majority of Americans now live in the suburbs.1 This was just the latest of many milestones in the history of the American suburbs. Since the United States emerged as an industrial power, suburbs have steadily grown from small upper-class rural retreats into the most prominent form of American communities. Yet, the dominance of suburbs in American society was not an inevitable outcome of industrialization, nor was it even clear before the latter half of the 19th century that the middle and upper classes would prefer to live in peripheral areas over the inner-city. Many historians and sociologists have attempted to explain why the first suburbs developed in the late 19th century. Sam Bass Warner, in his 1962 book, Streetcar Suburbs was the first to analyze the intricate process of early suburban development. In Streetcar Suburbs, Warner describes how Boston from 1850 to 1 Frank Hobbs and Nicole Stoops, U.S. Census Bureau, Census 2000 Special Reports, Series CENSR-4, Demographic Trends in the 20th Century (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2002), 33. 2 1900 transformed from a walking city to a modern metropolis. In 1850, Boston was made up of communities within 2 miles of the Central Business District (CDB) where wealthy merchants and the working class lived in close quarters. In the next fifty years, Boston evolved into a “two-part” city consisting of middle class commuter suburbs on the periphery of the city, and working class neighborhoods surrounding a CBD devoted almost entirely to office space and production. -

Amtrak General and Legislative Annual Report & FY2022 Grant Request

April , The Honorable Kamala Harris President of the Senate U.S. Capitol Washington, DC The Honorable Nancy Pelosi Speaker of the House of Representatives U.S. Capitol Washington, DC Dear Madam President and Madam Speaker: I am pleased to transmit Amtrak’s Fiscal Year (FY) General and Legislative Annual Report to Congress, which includes our FY grant request, legislative proposals, and a summary of the various actions taken by Amtrak to respond to the Coronavirus pandemic. To overcome the setbacks to service and financial performance we faced during this crisis, we seek Congress’s continued strong support in FY so that we can return to the successes and growth we accomplished in FY . Amtrak is poised to be a key part of the nation’s post-pandemic recovery and low-carbon transportation future, but to do so we require continued Federal government support, including robust investment. Despite the difficulties of the past year, Amtrak was able to achieve significant accomplishments and continue progressing vital initiatives, such as: . Safety: Completed Positive Train Control (PTC) installation and operation everywhere it was required across entire network and advanced our industry-leading Safety Management System (SMS). Moynihan Train Hall: Amtrak, in partnership with New York State and the Long Island Rail Road, opened the first modern, large-scale intercity train station built in the U.S. in over years. FY Capital Investment: Performed $. billion in infrastructure and fleet work. FY Ridership: Provided . million customer trips, which, while a decrease of . million passengers from FY owing to the pandemic-related travel reductions; reflects record performance during the five months preceding the onset of the Coronavirus.