Natural Resource Management in Syrian Villages (MSR XX, 2017)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 2014 Golden Gate National Parks Bioblitz - Data Management and the Event Species List Achieving a Quality Dataset from a Large Scale Event

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science The 2014 Golden Gate National Parks BioBlitz - Data Management and the Event Species List Achieving a Quality Dataset from a Large Scale Event Natural Resource Report NPS/GOGA/NRR—2016/1147 ON THIS PAGE Photograph of BioBlitz participants conducting data entry into iNaturalist. Photograph courtesy of the National Park Service. ON THE COVER Photograph of BioBlitz participants collecting aquatic species data in the Presidio of San Francisco. Photograph courtesy of National Park Service. The 2014 Golden Gate National Parks BioBlitz - Data Management and the Event Species List Achieving a Quality Dataset from a Large Scale Event Natural Resource Report NPS/GOGA/NRR—2016/1147 Elizabeth Edson1, Michelle O’Herron1, Alison Forrestel2, Daniel George3 1Golden Gate Parks Conservancy Building 201 Fort Mason San Francisco, CA 94129 2National Park Service. Golden Gate National Recreation Area Fort Cronkhite, Bldg. 1061 Sausalito, CA 94965 3National Park Service. San Francisco Bay Area Network Inventory & Monitoring Program Manager Fort Cronkhite, Bldg. 1063 Sausalito, CA 94965 March 2016 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. -

Prajitura Amandina

Mihaela11 - retetele mele (Gustos.ro) Mihaela11 Mihaela11 - retetele mele (Gustos.ro) Continut "Aish Saraya"( "Eish Saraya") ..................................................................................................... 1 "Spanakopita" .............................................................................................................................. 2 "Kabsa" cu pui si stafide .............................................................................................................. 2 Cheesecake "After eight"............................................................................................................. 4 Socata.......................................................................................................................................... 5 "Maglubeh bil foul akhdar"-"Maglubeh" cu pastai de bob verde de gradina ................................ 5 Placinta cu mere (de post).......................................................................................................... 6 Piept de pui umplut cu ardei si cascaval cu garnitura de legume la cuptor ................................. 7 Saratele spirale din aluat de foietaj.............................................................................................. 8 Sarmale din varza murata cu carne de vita ................................................................................. 8 Bruschete cu rosii, ardei si "za'atar" ............................................................................................ 9 Fasole batuta ( mai pe -

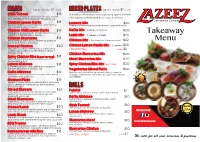

Mixed Plates

MAINS (skewer change $2 each) MIXED PLATES (skewer change $2 each) Shish Tawouk $15 A variety of hommos, baba ghanouj, garlic, falafel 3 skewers of marinated chicken breast, served on a bed of parsley and onion with garlic dip and tabouli served with your choice of main: Lebanese Cuisine Chicken Lemon Garlic $18 Lazeez Mix $20 Marinated diced chicken breast tossed in our Skewers of marinated chicken breast, lamb and kafta special lemon garlic sauce Chicken Chilli Lemon Garlic $19 Kafta Mix - 4 skewers of kafta $20 Marinated diced chicken breast tossed in our Takeaway special chilli lemon garlic sauce Lamb Mix - 3 skewers of lamb $23 Chicken Shawarma $14 Marinated chicken strips, served on a bed of Chicken Mix - 3 skewers of chicken breast $22 Menu parsley and onion with garlic Mansaf Chicken $20 Chicken Lemon Garlic Mix - 3 skewers $23 Mansaf rice topped with pieces of poached Add Chilli Paste extra chicken and mixed nuts, served with yoghurt $2 and cucumber Chicken Shawarma Mix $20 Spicy Chicken Ribs (6 per serving) $13 Oven-baked spicy marinated chicken ribs Meat Shawarma Mix $20 served with garlic Laham Mishwee $18 Spicy Chicken Ribs Mix (with Chips) $20 3 skewers of lamb rump, served on a bed of parsley and onion with garlic dip Vegetarian Mixed Plate $20 Kafta Mishwee $12 Mjadara served with vegetarian kibbeh, spinach 4 skewers of kafta, served on a bed of parsley triangle, vine leaves, tabouli, baba ghanouj, hommos and onion with garlic dip and falafel Mashawi Plate $15 Skewers of marinated chicken breast, lamb and kafta, served -

Perennial Grain Legume Domestication Phase I: Criteria for Candidate Species Selection

sustainability Review Perennial Grain Legume Domestication Phase I: Criteria for Candidate Species Selection Brandon Schlautman 1,2,* ID , Spencer Barriball 1, Claudia Ciotir 2,3, Sterling Herron 2,3 and Allison J. Miller 2,3 1 The Land Institute, 2440 E. Water Well Rd., Salina, KS 67401, USA; [email protected] 2 Saint Louis University Department of Biology, 1008 Spring Ave., St. Louis, MO 63110, USA; [email protected] (C.C.); [email protected] (S.H.); [email protected] (A.J.M.) 3 Missouri Botanical Garden, 4500 Shaw Blvd. St. Louis, MO 63110, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-785-823-5376 Received: 12 February 2018; Accepted: 4 March 2018; Published: 7 March 2018 Abstract: Annual cereal and legume grain production is dependent on inorganic nitrogen (N) and other fertilizers inputs to resupply nutrients lost as harvested grain, via soil erosion/runoff, and by other natural or anthropogenic causes. Temperate-adapted perennial grain legumes, though currently non-existent, might be uniquely situated as crop plants able to provide relief from reliance on synthetic nitrogen while supplying stable yields of highly nutritious seeds in low-input agricultural ecosystems. As such, perennial grain legume breeding and domestication programs are being initiated at The Land Institute (Salina, KS, USA) and elsewhere. This review aims to facilitate the development of those programs by providing criteria for evaluating potential species and in choosing candidates most likely to be domesticated and adopted as herbaceous, perennial, temperate-adapted grain legumes. We outline specific morphological and ecophysiological traits that may influence each candidate’s agronomic potential, the quality of its seeds and the ecosystem services it can provide. -

The Tribal Dimension in Mamluk-Jordanian Relations

BETHANY J. WALKER MISSOURI STATE UNIVERSITY The Tribal Dimension in Mamluk-Jordanian Relations A growing interest in provincial history is producing alternative understandings of Mamluk political culture, ones that recognize the contributions and influence of local actors. 1 Given the uniquely local perspective of Syrian sources, the frequency with which one encounters references to local families and their larger tribal networks is not surprising. Jordanian nisbahs are a staple of Syrian biographical dictionaries, waqfīyāt, and chronicles of the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, indicating the degree to which the peoples of Transjordan participated in the cultural, intellectual, economic, and indeed political life of the time in southern Syria. Malkawis, Ḥisbānīs, and Ḥubrasis made academic careers in Damascus, Jerusalem, and Cairo and were active in Sufi organizations outside their home towns; Shobakis acquired land at an early stage in the development of private estates, endowing much of it as family and charitable awqāf at the turn of the ninth/fifteenth century; ʿAjlūnīs controlled markets and were successful in business; Kerakis were a constant challenge to the state in the fifteenth century, playing an active role in rebellions of myriad forms. 2 These teachers, businessmen, and rebels, regardless of where they were actually born and raised, traced their © The Middle East Documentation Center. The University of Chicago. 1 Yūsuf Ghawānimah, Al-Tārīkh al-Ḥaḍarī li-Sharq al-Urdunn fī al-ʿAṣr al-Mamlūkī (Amman, 1982); idem, Al-Tārīkh al-Siyāsī li-Sharq al-Urdunn fī ʿAṣr al-Mamlūkī al-Awwal (al-Mamālīk al-Baḥrīyah) (Amman, 1982); and idem, Dimashq fī ʿAṣr Dawlat al-Mamālīk al-Thānīyah (Amman, 2005); Taha Tarawneh [Tarāwinah], The Province of Damascus during the Second Mamluk Period (784/1382– 922/1516) (Irbid, 1987); Alexandrine Guérin, “Terroirs, Territoire et Peuplement en Syrie Méridionale à la Période Islamique (VIIe siècle–XVIe siècle): Étude de Cas: le Village de Msayké et la Région du Lağa” (Ph.D. -

SFAN Early Detection V1.4

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Early Detection of Invasive Plant Species in the San Francisco Bay Area Network A Volunteer-Based Approach Natural Resource Report NPS/SFAN/NRR—2009/136 ON THE COVER Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy employee Elizabeth Speith gathers data on an invasive Cotoneaster shrub. Photograph by: Andrea Williams, NPS. Early Detection of Invasive Plant Species in the San Francisco Bay Area Network A Volunteer-Based Approach Natural Resource Report NPS/SFAN/NRR—2009/136 Andrea Williams Marin Municipal Water District Sky Oaks Ranger Station 220 Nellen Avenue Corte Madera, CA 94925 Susan O'Neil Woodland Park Zoo 601 N 59th Seattle, WA 98103 Elizabeth Speith USGS NBII Pacific Basin Information Node Box 196 310 W Kaahumau Avenue Kahului, HI 96732 Jane Rodgers Socio-Cultural Group Lead Grand Canyon National Park PO Box 129 Grand Canyon, AZ 86023 August 2009 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Program Center publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate high-priority, current natural resource management information with managerial application. The series targets a general, diverse audience, and may contain NPS policy considerations or address sensitive issues of management applicability. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. -

03 Fragia.Indd

JIA 6.2 (2019) 187–208 Journal of Islamic Archaeology ISSN (print) 2051-9710 https://doi.org/10.1558/jia.37337 Journal of Islamic Archaeology ISSN (print) 2051-9729 New Research Perspectives on the Mamluk Qāʾa at Kerak Castle: Building Archaeology and Historical Contextualization Lorenzo Fragai Ph D Candidate “La Sapienza” University of Rome University of Florence, “Medieval Petra” Archaeological Mission [email protected] The Mamluk dynasty (1250–1517) succeeded the Ayyubids in Egypt and Syria. From 1260, and for 260 years, construction projects and different types of buildings were sponsored by sultans, emirs, and members of the elite in Cairo, Damascus and Jerusa- lem as well as in smaller towns and regions on the outskirts of the Mamluk sultanate. Although the existing architecture from the Mamluk period is generally well known in Egypt and Syria, this is not always the case in other countries. In present-day Jordan, which was divided administratively into two large mamlakats, there are many sumptuous examples of mamluk buildings that still have yet to be investigated with the necessary attention. The case study ana- lysed here is the castrum/qalʿat Kerak in the late 13th and the first half of 14th century, where an exceptional example of Mamluk palatine architecture is partially preserved. According to written historical sources, this reception hall (or qāʾa) called Qā’at al-Naḥḥās can be attributed to al-Nāṣir Muḥammad ibn Qalāwūn (1310–1341), one of the most distinguished figure of the Mamluk sultanate. This paper will undertake to clarify the construction process of Mamluk royal spaces in Kerak as evidence of the Mamluk dynasty’s power and stability, using the methods of “Light Archaeology” (building stratigraphy, in particular) already used by the Italian archaeo- logical mission (University of Florence) at Petra and Shawbak (Medieval Petra project). -

A New Cultivar of White Lupin with Determined Bushy Growth Habit, Sweet Grain and High Protein Content

SCIENTIFIC NOTE 577 PECOSA-BAER: A NEW CULTIVAR OF WHITE LUPIN WITH DETERMINED BUSHY GROWTH HABIT, SWEET GRAIN AND HIGH PROTEIN CONTENT Erik von Baer1*, Ingrid von Baer1, and Ricardo Riegel2 ABSTRACT The expansion of white lupin (Lupinus albus L.) cultivation in Chile is subject to the availability of cultivars presenting high yield potential, tolerance to the main fungal diseases and homogeneous ripening. In response to these requirements, a new cultivar has been developed and registered as ‘Liapec-1’, commercially registered as ‘Pecosa-Baer’. This new cultivar has determined bushy growth habit. Its flowering period is concentrated in approximately 40 days, less than the 77 days of cv. Rumbo-Baer. This trait allows it to reach harvest without heterogeneity problems. The seed is speckled, flat and medium-sized (370 g/1000 grains aprox.). The kernels are sweet and have a high protein content of around 41% (dry matter basis). In field assays, ‘Pecosa-Baer’ presents a good tolerance to diseases caused by Colletotrichum lupini and Pleiochaeta setosa. The new cultivar has outstanding stability and yield levels, even under low fertilization conditions. An average yield of 5.43 t ha-1 was obtained over four seasons in two locations. In order to maximize its yield, ‘Pecosa-Baer’ must be sown between April and June at a rate of 140-160 kg ha-1. Given the high protein content and low alkaloid levels of the seeds, they can be included in the diet of all types of animals. Key words: Lupinus albus, cultivar, Colletotrichum, Pleiochaeta. INTRODUCTION Servicio Agrícola y Ganadero (SAG) the cvs. -

Mr Shawarma Latest V4

KIBBEH NAYEH (raw) 16.0 HOMMOS w/SHAWARMA 16.0 TABOULI 15.0 CHICKEN WRAP 10.0 Finely grounded raw minced meat blended with finely Blended chick peas, tahini & lemon, garnished with Finely chopped tomatoes, parsley, mint, finely cracked Chicken shawarma with pickles, hot chips & garlic sauce cracked wheat, onions, walnuts & mint, dressed with paprika & olive oil, topped with meat shawarma wheat, onion with olive oil & lemon juice dressing olive oil MEAT WRAP 12.0 LENTIL SOUP 8.0 FATTOUSH 16.0 Shawarma with parsley, onion, tomato, pickles & tahini sauce KIBBEH (fried) 12.0 Yellow lentil slow cooked with onion & olive oil Lettuce, tomato, cucumber, radish, parsley, shallots, crispy Minced meat, onion & spices stuffed inside a blend of fried bread with pomegranate molasses, fresh lemon juice, MIXED WRAP 12.0 kibbeh meat & finely cracked wheat, deep fried (4 per FALAFEL PLATE 10.0 garlic & olive oil dressing Chicken & meat with parsley, onion, tomato, pickles & tahini serving) Chickpeas, fresh garlic, herbs & spice mix, served with t sauce ahini sauce GARDEN SALAD 17.0 SAMBOSIQ (meat) 12.0 Lettuce, tomato, cucumber, onion with lemon juice, dried KAFTA WRAP 10.0 Deep fried pastry pockets filled with minced meat, onions HOT CHIPS 10.0 mint & olive oil dressing Kafta with parsley, onion, tomato, pickles & hommos sauce & herbs Served with your choice of sauce COLESLAW 14.0 TAWOUK WRAP 12.0 SAMBOSIQ (cheese) 12.0 Finely shredded raw cabbage & shredded carrots, dressed Chicken shish tawouk with coleslaw, tomato, pickles, hot BABA GHANOUJ w/CHICKEN -

Molecular Detection of Bean Yellow Mosaic Virus in Lupinus Albus

ls & vira An ti ti n re A t r f o o v l Barakat and Torky, J Antivir Antiretrovir 2017, 9:2 i r a a Journal of n l r s u DOI: 10.4172/1948-5964.1000159 o J ISSN: 1948-5964 Antivirals & Antiretrovirals Research Article Article Open Access Molecular Detection of Bean Yellow Mosaic Virus in Lupinus albus Plants and its Associated Alterations in Biochemical and Physiological Parameters Ahmed Barakat and Zenab Aly Torky* Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Science, Ain Shams University, Egypt Abstract Bean yellow mosaic virus is one of the most devastating diseases of cultivated Leguminosae plants worldwide causing mosaic, mottling, malformation and distortion in infected cultivar plants. Present study was conducted to investigate the possibility of infection of Lupinus albus (Lupine) with Bean yellow mosaic virus. Virus isolate was identified by detection of the coat protein gene amplified by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and also via Chenopodium Amaranticolor as a diagnostic host plant. Results showed that infection can be induced under greenhouse conditions and infected plants showed a considerable level of mosaic symptoms. As disease development in infected plants is always associated with physiological and chemical changes, some metabolic alterations parameters have been evaluated like photosynthetic pigment contents, total carbohydrate content, total soluble protein, total protein, total free amino acid, proline induction, total phenolics, salicylic acid, and abscisic acid content in healthy and infected lupine plants. Results showed a great variation in all the biochemical categories in Lupinus albus infected with bean yellow mosaic virus as compared to healthy plants. -

2011-BAS-Al Hadheerah Menu-EN

DATES AND DRY FRUITS DISPLAY ARABIC BREAD DISPLAY Arabic Bread Egyptian Bread Lebanese Bread Turkish Bread Arabic Grissini Pita Bread Bread Khameer Moroccan Bread SALAD ON THE TABLE Hummus - Mutable - Labneh - Muhammara - Arabic Pickles SALAD BAR Hummus Mutable Rocca Salad Muhammara Fattoush Tabbouleh Waraq Eneb Moussaka Cous Cous Salad Labneh Baba Ganoush Hindbeh Loubieh Bel Zejt Mujaddara Arabic Salad Green Bar Mixed Pickle Olives Onion Pickle Carrot Pickle Turnip Pickle Cucumber Pickle Cauliflower Pickle Chili Pickle ARABIC CHEESE DISPLAY Roumy Feta Halloumi Baladi Shellal Shanklish Nabulsi Domiati Labneh Balls - Spicy - Herb - Plain Kashkawan Arrish Akawi HOT MEZZEH SELECTION Cheese Sambousek Spinach Fatayer Meat Sambousek Lamb Kibbeh Cauliflower Fried Eggplant Falafel TRIPOD STANDS Lentil Soup Vermicelli Soup Baked Potatoes Steamed Vegetable Iranian Rice Steam Rice Meammar Rice Okra Stew SHAWARMA STATION Chicken - Beef Condiments ARABIC GRILLS Shish Tawouk Jorge Kebab Lamb Kofta Lamb Kebab Kebab Halabi Chicken Wings SEAFOOD STATION Poached Crab Fresh Fish Lobster Tail Calamari Prawns Fried Fish GRILLS Beef Tenderloin Lamb Chops Beef Striploin Chicken Breast Turkish Sucuk LOCAL SELECTION Chicken Tahta Lamb Harees Samak Salona Marag Bil Hudra MAINS Lebanese Chicken Fatteh Lamb Mansaf Fish Tagine Shish Barak AL HADHEERAH DESERT RESTAURENT MEGALGAL Chicken Liver, Pomegranate Molasses MANAKEESH COUNTER Cheese Za'atar Lahma Saj Arayes AL HADHEERAH SPECIALS Split Grilled Chicken Bolar Blade Underground Makmour Roasted Local Ouzi with Saffron Rice DESSERTS Arabic Ice Cream Counter Turkish Delight Chocolate Fountain Znoud El Site Katayef Ashta Katayef Walnuts Kellaj Stouf Osmaliya Ashta Kunafa Cheese Coconut Namours Basbousa Laquimat Umali Muhalabiya Ayesha Al Saraya Rice Pudding Barazek Awamat Mafroukeh Baklawa Moroccan Sweets Fresh Fruit Display AL HADHEERAH DESERT RESTAURENT. -

Species of Malva L. (Malvaceae) Cultivated in the Western of Santa Catarina State and Conformity with Species Marketed As Medicinal Plants in Southern Brazil

Journal of Agricultural Science; Vol. 11, No. 15; 2019 ISSN 1916-9752 E-ISSN 1916-9760 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Species of Malva L. (Malvaceae) Cultivated in the Western of Santa Catarina State and Conformity With Species Marketed as Medicinal Plants in Southern Brazil Leyza Paloschi de Oliveira1, Massimo Giuseppe Bovini2, Roseli Lopes da Costa Bortoluzzi1, Mari Inês Carissimi Boff1 & Pedro Boff3 1 Programa de Pós-graduação em Produção Vegetal, Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina, Lages, Santa Catarina Brazil 2 Instituto de Pesquisas Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 3 Laboratório de Homeopatia e Saúde Vegetal, Empresa de Pesquisa Agropecuária e Extensão Rural de Santa Catarina (EPAGRI), Lages, Santa Catarina, Brazil Correspondence: Leyza Paloschi de Oliveira, Programa de Pós-graduação em Produção Vegetal, Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina, Centro de Ciências Agroveterinárias, Av. Luiz de Camões 2090, Conta Dinheiro, CEP 88.520-000, Lages, Brazil. Tel: 55-499-9912-6147. E-mail: [email protected] Received: June 3, 2019 Accepted: July 12, 2019 Online Published: September 15, 2019 doi:10.5539/jas.v11n15p171 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/jas.v11n15p171 Abstract The Malva genus presents different species with therapeutic potential and inadequate consumption can occur due to the incorrect identification of the plant in the market. The objective of this study was to identify species of the Malva genus cultivated in the Western Mesoregion of Santa Catarina State-Southern Brazil, and to verify the conformity of products’ labels marketed as dehydrated medicinal plants through the characteristics of the plant parts.