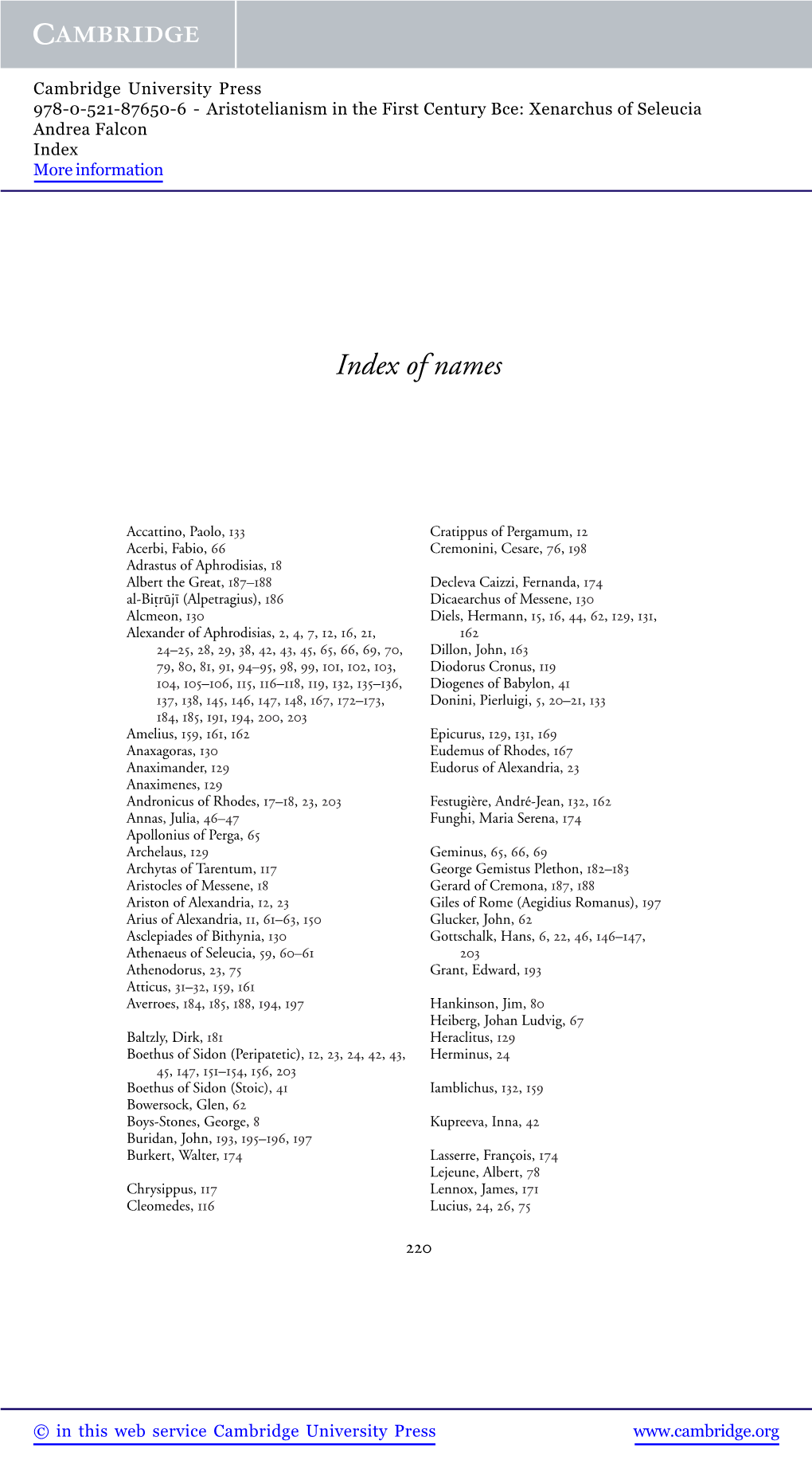

Index of Names

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aristotle's Categories in the Early Roman Empire, Oxford: Oxford University Press 2015, in Sehepunkte 15 (2015), Nr

Citation style Andrea Falcon: Rezension von: Michael J. Griffin: Aristotle's Categories in the Early Roman Empire, Oxford: Oxford University Press 2015, in sehepunkte 15 (2015), Nr. 7 [15.07.2015], URL:http://www.sehepunkte.de/2015/07/27098.html First published: http://www.sehepunkte.de/2015/07/27098.html copyright This article may be downloaded and/or used within the private copying exemption. Any further use without permission of the rights owner shall be subject to legal licences (§§ 44a-63a UrhG / German Copyright Act). sehepunkte 15 (2015), Nr. 7 Michael J. Griffin: Aristotle's Categories in the Early Roman Empire This is a book about the reception of Aristotle's Categories from the first century BC to the second century AD. The Categories does not appear to have circulated in the Hellenistic era. By contrast, this short but enigmatic treatise was at the center of the so-called return to Aristotle in the first century BC. The book under review tells us the story of this remarkable reversal of fortune. The main characters in this story are philosophers working in the three main philosophical traditions of post- Hellenistic philosophy. For the Peripatetic tradition, these are Andronicus of Rhodes and Boethus of Sidon. For the Academic and Platonic tradition, Eudorus of Alexandria and Lucius. For the Stoic tradition, Athenodorus and Cornutus. A supporting role is reserved to the following interpreters of the Categories : Aristo of Alexandria, Ps-Archytas, Nicostratus, Aspasius, Herminus, and Adrastus. In broad outline, the story told in the book goes as follows: Andronicus of Rhodes rescued the Categories from obscurity by deciding to place it at the beginning of his catalogue of Aristotle's writings (chapter 2). -

Aristotelianism in the First Century BC

CHAPTER 5 Aristotelianism in the First Century BC Andrea Falcon 1 A New Generation of Peripatetic Philosophers The division of the Peripatetic tradition into a Hellenistic and a post- Hellenistic period is not a modern invention. It is already accepted in antiquity. Aspasius speaks of an old and a new generation of Peripatetic philosophers. Among the philosophers who belong to the new generation, he singles out Andronicus of Rhodes and Boethus of Sidon.1 Strabo adopts a similar division. He too distinguishes between the older Peripatetics, who came immediately after Theophrastus, and their successors.2 He collectively describes the latter as better able to do philosophy in the manner of Aristotle (φιλοσοφεῖν καὶ ἀριστοτελίζειν). It remains unclear what Strabo means by doing philosophy in the manner of Aristotle.3 But he certainly thinks that the philosophers who belong to the new generation, and not those who belong to the old one, deserve the title of true Aristotelians. For Strabo, the event separating the old from the new Peripatos is the rediscovery and publication of Aristotle’s writings. We may want to resist Strabo’s negative characterization of the earlier Peripatetics. For Strabo, they were not able to engage in philosophy in any seri- ous way but were content to declaim general theses.4 This may be an unfair judgment, ultimately based on the anachronistic assumption that any serious philosophy requires engagement with an authoritative text.5 Still, the empha- sis that Strabo places on the rediscovery of Aristotle’s writings suggests that the latter were at the center of the critical engagement with Aristotle in the 1 Aspasius, On Aristotle’s Ethics 44.20–45.16. -

Theon of Alexandria and Hypatia

CREATIVE MATH. 12 (2003), 111 - 115 Theon of Alexandria and Hypatia Michael Lambrou Abstract. In this paper we present the story of the most famous ancient female math- ematician, Hypatia, and her father Theon of Alexandria. The mathematician and philosopher Hypatia flourished in Alexandria from the second part of the 4th century until her violent death incurred by a mob in 415. She was the daughter of Theon of Alexandria, a math- ematician and astronomer, who flourished in Alexandria during the second part of the fourth century. Information on Theon’s life is only brief, coming mainly from a note in the Suda (Suida’s Lexicon, written about 1000 AD) stating that he lived in Alexandria in the times of Theodosius I (who reigned AD 379-395) and taught at the Museum. He is, in fact, the Museum’s last attested member. Descriptions of two eclipses he observed in Alexandria included in his commentary to Ptolemy’s Mathematical Syntaxis (Almagest) and elsewhere have been dated as the eclipses that occurred in AD 364, which is consistent with Suda. Although originality in Theon’s works cannot be claimed, he was certainly immensely influential in the preservation, dissemination and editing of clas- sic texts of previous generations. Indeed, with the exception of Vaticanus Graecus 190 all surviving Greek manuscripts of Euclid’s Elements stem from Theon’s edition. A comparison to Vaticanus Graecus 190 reveals that Theon did not actually change the mathematical content of the Elements except in minor points, but rather re-wrote it in Koini and in a form more suitable for the students he taught (some manuscripts refer to Theon’s sinousiai). -

Platonist Philosopher Hypatia of Alexandria in Amenabar’S Film Agorá

A STUDY OF THE RECEPTION OF THE LIFE AND DEATH OF THE NEO- PLATONIST PHILOSOPHER HYPATIA OF ALEXANDRIA IN AMENABAR’S FILM AGORÁ GILLIAN van der HEIJDEN Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Faculty of Humanities School of Religion, Philosophy and Classics at the UNIVERSITY OF KWAZULU-NATAL, DURBAN SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR J.L. HILTON MARCH 2016 DECLARATION I, Gillian van der Heijden, declare that: The research reported in this dissertation, except where otherwise indicated, is my original research; This dissertation has not been submitted for any degree or examination at any other university; This dissertation does not contain other persons’ data, pictures, graphs or other information, unless specifically acknowledged as being sourced from other persons; The dissertation does not contain other persons’ writing, unless specifically acknowledged as being sourced from other researchers. Where other written sources have been quoted, then: a) their words have been re-written but the general information attributed to them has been referenced; b) where their exact words have been used, their writing has been paragraphed and referenced; c) This dissertation/thesis does not contain text, graphics or tables copied and pasted from the Internet, unless specifically acknowledged, and the source being detailed in the dissertation/thesis and in the References sections. Signed: Gillian van der Heijden (Student Number 209541374) Professor J. L. Hilton ii ABSTRACT The film Agorá is better appreciated through a little knowledge of the rise of Christianity and its opposition to Paganism which professed ethical principles inherited from Greek mythology and acknowledged, seasonal rituals and wealth in land and livestock. -

Athenaeus' Reading of the Aulos Revolution ( Deipnosophistae 14.616E–617F)

The Journal of Hellenic Studies http://journals.cambridge.org/JHS Additional services for The Journal of Hellenic Studies: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here New music and its myths: Athenaeus' reading of the Aulos revolution ( Deipnosophistae 14.616e–617f) Pauline A. Leven The Journal of Hellenic Studies / Volume 130 / November 2010, pp 35 - 48 DOI: 10.1017/S0075426910000030, Published online: 19 November 2010 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0075426910000030 How to cite this article: Pauline A. Leven (2010). New music and its myths: Athenaeus' reading of the Aulos revolution ( Deipnosophistae 14.616e– 617f). The Journal of Hellenic Studies, 130, pp 35-48 doi:10.1017/S0075426910000030 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/JHS, IP address: 147.91.1.45 on 23 Sep 2013 Journal of Hellenic Studies 130 (2010) 35−47 DOI: 10.1017/S0075426910000030 NEW MUSIC AND ITS MYTHS: ATHENAEUS’ READING OF THE AULOS REVOLUTION (DEIPNOSOPHISTAE 14.616E−617F) PAULINE A. LEVEN Yale University* Abstract: Scholarship on the late fifth-century BC New Music Revolution has mostly relied on the evidence provided by Athenaeus, the pseudo-Plutarch De musica and a few other late sources. To this date, however, very little has been done to understand Athenaeus’ own role in shaping our understanding of the musical culture of that period. This article argues that the historical context provided by Athenaeus in the section of the Deipnosophistae that cites passages of Melanippides, Telestes and Pratinas on the mythology of the aulos (14.616e−617f) is not a credible reflection of the contemporary aesthetics and strategies of the authors and their works. -

Historical Synopsis of the Aristotelian Commentary Tradition (In Less Than Sixty Minutes)

HISTORICAL SYNOPSIS OF THE ARISTOTELIAN COMMENTARY TRADITION (IN LESS THAN SIXTY MINUTES) Fred D. Miller, Jr. CHAPTER 1 PERIPATETIC SCHOLARS Aristotle of Stagira (384–322 BCE) Exoteric works: Protrepticus, On Philosophy, Eudemus, etc. Esoteric works: Categories, Physics, De Caelo, Metaphysics, De Anima, etc. The legend of Aristotle’s misappropriated works Andronicus of Rhodes: first edition of Aristotle’s works (40 BCE) Early Peripatetic commentators Boethus of Sidon (c. 75—c. 10 BCE) comm. on Categories Alexander of Aegae (1st century CE)comm. on Categories and De Caelo Adrastus of Aphrodisias (early 1st century) comm. on Categories Aspasius (c. 131) comm. on Nicomachean Ethics Emperor Marcus Aurelius establishes four chairs of philosophy in Athens: Platonic, Peripatetic, Stoic, Epicurean (c. 170) Alexander of Aphrodisias (late 2nd —early 3rd century) Extant commentaries on Prior Analytics, De Sensu, etc. Lost comm. on Physics, De Caelo, etc. Exemplar for all subsequent commentators. Comm. on Aristotle’s Metaphysics Only books 1—5 of Alexander’s comm. are genuine; books 6—14 are by ps.-Alexander . whodunit? Themistius (c. 317—c. 388) Paraphrases of Physics, De Anima, etc. Paraphrase of Metaphysics Λ (Hebrew translation) Last of the Peripatetics CHAPTER 2 NEOPLATONIC SCHOLARS Origins of Neoplatonism Ammonius Saccas (c. 175—242) forefather of Neoplatonism Plotinus (c. 205—260) the Enneads Reality explained in terms of hypostases: THE ONE—> THE INTELLECT—>WORLD SOUL—>PERCEPTIBLE WORLD Porphyry of Tyre (232–309) Life of Plotinus On the School of Plato and Aristotle Being One On the Difference Between Plato and Aristotle Isagoge (Introduction to Aristotle’s Categories) What is Neoplatonism? A broad intellectual movement based on the philosophy of Plotinus that sought to incorporate and reconcile the doctrines of Plato, Pythagoras, and Aristotle with each other and with the universal beliefs and practices of popular religion (e.g. -

Pappus of Alexandria: Book 4 of the Collection

Pappus of Alexandria: Book 4 of the Collection For other titles published in this series, go to http://www.springer.com/series/4142 Sources and Studies in the History of Mathematics and Physical Sciences Managing Editor J.Z. Buchwald Associate Editors J.L. Berggren and J. Lützen Advisory Board C. Fraser, T. Sauer, A. Shapiro Pappus of Alexandria: Book 4 of the Collection Edited With Translation and Commentary by Heike Sefrin-Weis Heike Sefrin-Weis Department of Philosophy University of South Carolina Columbia SC USA [email protected] Sources Managing Editor: Jed Z. Buchwald California Institute of Technology Division of the Humanities and Social Sciences MC 101–40 Pasadena, CA 91125 USA Associate Editors: J.L. Berggren Jesper Lützen Simon Fraser University University of Copenhagen Department of Mathematics Institute of Mathematics University Drive 8888 Universitetsparken 5 V5A 1S6 Burnaby, BC 2100 Koebenhaven Canada Denmark ISBN 978-1-84996-004-5 e-ISBN 978-1-84996-005-2 DOI 10.1007/978-1-84996-005-2 Springer London Dordrecht Heidelberg New York British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Control Number: 2009942260 Mathematics Classification Number (2010) 00A05, 00A30, 03A05, 01A05, 01A20, 01A85, 03-03, 51-03 and 97-03 © Springer-Verlag London Limited 2010 Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licenses issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. -

Early Pyrrhonism As a Sect of Buddhism? a Case Study in the Methodology of Comparative Philosophy

Comparative Philosophy Volume 9, No. 2 (2018): 1-40 Open Access / ISSN 2151-6014 / www.comparativephilosophy.org https://doi.org/10.31979/2151-6014(2018).090204 EARLY PYRRHONISM AS A SECT OF BUDDHISM? A CASE STUDY IN THE METHODOLOGY OF COMPARATIVE PHILOSOPHY MONTE RANSOME JOHNSON & BRETT SHULTS ABSTRACT: We offer a sceptical examination of a thesis recently advanced in a monograph published by Princeton University Press entitled Greek Buddha: Pyrrho’s Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia. In this dense and probing work, Christopher I. Beckwith, a professor of Central Eurasian studies at Indiana University, Bloomington, argues that Pyrrho of Elis adopted a form of early Buddhism during his years in Bactria and Gandhāra, and that early Pyrrhonism must be understood as a sect of early Buddhism. In making his case Beckwith claims that virtually all scholars of Greek, Indian, and Chinese philosophy have been operating under flawed assumptions and with flawed methodologies, and so have failed to notice obvious and undeniable correspondences between the philosophical views of the Buddha and of Pyrrho. In this study we take Beckwith’s proposal and challenge seriously, and we examine his textual basis and techniques of translation, his methods of examining passages, his construal of problems and his reconstruction of arguments. We find that his presuppositions are contentious and doubtful, his own methods are extremely flawed, and that he draws unreasonable conclusions. Although the result of our study is almost entirely negative, we think it illustrates some important general points about the methodology of comparative philosophy. Keywords: adiaphora, anātman, anattā, ataraxia, Buddha, Buddhism, Democritus, Pāli, Pyrrho, Pyrrhonism, Scepticism, trilakṣaṇa 1. -

Seneca and Paul on the Future of Humanity and of the Cosmos

The Salvation of Creation: Seneca and Paul on the Future of Humanity and of the Cosmos James P. Ware Modern scholarship confirms what Seneca says about himself: that he was a convinced Stoic, who was nonetheless not averse to criticism of his Stoic predecessors, who drew eclectically upon a variety of thinkers regardless of school, and also sought to make original contributions to philosophical thought.1 The starting point for our examination, in Part One, of Seneca’s un- derstanding of the future of human beings and of the cosmos will therefore be the ancient Stoic conception of cosmic conflagration and renewal. In con- trast with Seneca, there is widespread disagreement (and, I will argue, misun- derstanding) in Pauline scholarship regarding the proper contextualization of Paul’s eschatology within its ancient philosophical and cultural milieu. In Part Two, therefore, our examination of Paul’s future expectation, I will address this debate regarding Paul’s eschatological hope. The aim will be to gain an au- thentic grasp of the content of Paul’s hope of resurrection and new creation, in order to set Paul and Seneca in fruitful dialogue regarding the cosmos, human beings, and their future. 1 Part One: Seneca and the Expectation of Eternal Recurrence The mainstream Stoic teaching postulated the cyclical or periodic destruc- tion by fire (ἐκπύρωσις) and subsequent renewal (παλιγγενεσία), in its identical form, of the entire created order.2 According to the Stoics, says Origen, “after the conflagration of the universe, which has taken place from infinity and will take place to infinity, the same order of all things, from beginning to end, has 1 See, e.g., Ep. -

Origins of Astrolabe Theory the Origins of the Astrolabe Were in Classical Greece

What is an Astrolabe? The astrolabe is a very ancient astronomical computer for solving problems relating to time and the position of the Sun and stars in the sky. Several types of astrolabes have been made. By far the most popular type is the planispheric astrolabe, on which the celestial sphere is projected onto the plane of the equator. A typical old astrolabe was made of brass and was about 6 inches (15 cm) in diameter, although much larger and smaller ones were made. Astrolabes are used to show how the sky looks at a specific place at a given time. This is done by drawing the sky on the face of the astrolabe and marking it so positions in the sky are easy to find. To use an astrolabe, you adjust the moveable components to a specific date and time. Once set, the entire sky, both visible and invisible, is represented on the face of the instrument. This allows a great many astronomical problems to be solved in a very visual way. Typical uses of the astrolabe include finding the time during the day or night, finding the time of a celestial event such as sunrise or sunset and as a handy reference of celestial positions. Astrolabes were also one of the basic astronomy education tools in the late Middle Ages. Old instruments were also used for astrological purposes. The typical astrolabe was not a navigational instrument although an instrument called the mariner's astrolabe was widely used. The mariner's astrolabe is simply a ring marked in degrees for measuring celestial altitudes. -

Hypatia of Alexandria Anne Serban

Hypatia of Alexandria Anne Serban Hypatia's Life Hypatia of Alexandria was born sometime between the years 350 to 370 AD in Alexandria of Egypt. She was the only daughter of Theon of Alexandria; no information exists about her mother. "Hypatia may have had a brother, Epiphanius, though he may have been only Theon's favorite pupil." Theon did not want to force his daughter to become the typical woman described by historian Slatkin when he wrote "Greek women of all classes were occupied with the same type of work, mostly centered around the domestic needs of the family. Women cared for young children, nursed the sick, and prepared food." Instead he educated her in math, astronomy and philosophy, as well as in different religions. Theons desire that his daughter be different from the mold that society created for women influenced the rest of Hypatias life. Eventually Hypatia became a teacher herself. She instructed her pupils, who were both pagans and Christians, in math, astronomy, and philosophy, focusing mostly on Neoplatonism. She also held lectures on various topics, often drawing many eager listeners. Her greatest contributions benefitted the fields of mathematics and astronomy. By 400 AD, she became the head of the Platonist school in Alexandria. "Hypatia, on the other hand, led the life of a respected academic at Alexandria's university; a position to which, as far as the evidence suggests, only males were entitled previously." Hypatia took many of Platos ideas as personal applications, choosing even to live a life of celibacy. Furthermore, Hypatia wrote three commentaries and worked with Theon on several books. -

6 X 10.Three Lines .P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-88480-8 - Peripatetic Philosophy 200 BC to AD 200: An Introduction and Collection of Sources in Translation Robert W. Sharples Excerpt More information Introduction This Introduction and the chronological table that follows it are intended to give readers who may not be familiar with this period of Peripatetic philosophy a guide to the major trends and developments, and to introduce some of the philosophers who will be considered in the following pages. The actual ancient evidence relating to some of the identifications and dates will be found below in Chapter 1, ‘People’. Aristotle’s school, the Lyceum, has been regarded both in antiquity and by modern scholars as entering a period of decline after its third head, Strato. This impression may in part be the result of tendentious representa- 1 tion in the ancient evidence, but in so far as it is accurate, the fundamental reason for the decline seems to be, not that Aristotle’s works were no longer available (below, 2), but that the Lyceum had never had an agenda that was philosophical in the narrow sense of that term predominant in antiquity, as promoting a way of life and an attitude towards its events. From Aristotle himself onwards, the concern of the school had largely been with the collecting and analysis of information on a wide range of topics, and it thus suffered from the double disadvantage that, on the one hand, it did not have such a clear evangelical message to propound as did the Epicureans or the Stoics (for the message of Nicomachean Ethics 10, that the highest human activity is theoretical study for its own sake, was probably of no wider appeal in antiquity than it is now), and, on the other, that such 2 research was being carried on elsewhere, above all in Ptolemaic Alexandria.