Efficacy of Psychotropic Drugs in Functional Dyspepsia: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Product List March 2019 - Page 1 of 53

Wessex has been sourcing and supplying active substances to medicine manufacturers since its incorporation in 1994. We supply from known, trusted partners working to full cGMP and with full regulatory support. Please contact us for details of the following products. Product CAS No. ( R)-2-Methyl-CBS-oxazaborolidine 112022-83-0 (-) (1R) Menthyl Chloroformate 14602-86-9 (+)-Sotalol Hydrochloride 959-24-0 (2R)-2-[(4-Ethyl-2, 3-dioxopiperazinyl) carbonylamino]-2-phenylacetic 63422-71-9 acid (2R)-2-[(4-Ethyl-2-3-dioxopiperazinyl) carbonylamino]-2-(4- 62893-24-7 hydroxyphenyl) acetic acid (r)-(+)-α-Lipoic Acid 1200-22-2 (S)-1-(2-Chloroacetyl) pyrrolidine-2-carbonitrile 207557-35-5 1,1'-Carbonyl diimidazole 530-62-1 1,3-Cyclohexanedione 504-02-9 1-[2-amino-1-(4-methoxyphenyl) ethyl] cyclohexanol acetate 839705-03-2 1-[2-Amino-1-(4-methoxyphenyl) ethyl] cyclohexanol Hydrochloride 130198-05-9 1-[Cyano-(4-methoxyphenyl) methyl] cyclohexanol 93413-76-4 1-Chloroethyl-4-nitrophenyl carbonate 101623-69-2 2-(2-Aminothiazol-4-yl) acetic acid Hydrochloride 66659-20-9 2-(4-Nitrophenyl)ethanamine Hydrochloride 29968-78-3 2,4 Dichlorobenzyl Alcohol (2,4 DCBA) 1777-82-8 2,6-Dichlorophenol 87-65-0 2.6 Diamino Pyridine 136-40-3 2-Aminoheptane Sulfate 6411-75-2 2-Ethylhexanoyl Chloride 760-67-8 2-Ethylhexyl Chloroformate 24468-13-1 2-Isopropyl-4-(N-methylaminomethyl) thiazole Hydrochloride 908591-25-3 4,4,4-Trifluoro-1-(4-methylphenyl)-1,3-butane dione 720-94-5 4,5,6,7-Tetrahydrothieno[3,2,c] pyridine Hydrochloride 28783-41-7 4-Chloro-N-methyl-piperidine 5570-77-4 -

Impact of Itopride and Domperidone on Sensitivity of Gastric Distention and Gastric Accommodation in Healthy Volunteers

Impact of Itopride and Domperidone on sensitivity of gastric distention and gastric accommodation in healthy volunteers. Karen Van den Houte, Florencia Carbone, Ans Pauwels, Rita Vos, Tim Vanuytsel, Jan Tack Translational Research Center for Gastrointestinal Disorders, KULeuven, Belgium BACKGROUND & AIM RESULTS Functional dyspepsia (FD), defined as upper abdominal symptoms affecting Conduct of the study Gastric accommodation daily life, as postprandial fullness, early satiation, epigastric pain, and epigastric • 15 healthy volunteers (9 female, 6 male) • No significant differences in VAS scores before and after meal burning, without any underlying organic disease, is one of the most common • Mean age: 28.3±5.8 years ingestion and no significant differences in preprandial intragastric functional gastrointestinal disorders (1). volumes were observed. Itopride, a prokinetic drug with dopamine D2-antagonistic and cholinesterase Gastric compliance and gastric sensitivity • Postprandial gastric volumes and gastric accommodation were inhibitor properties, is frequently used to treat functional dyspepsia. Its effects I50, I100, and D10 did not affect fasting or postprandial gastric significantly lower for I50 and for D10, compared to placebo. on gastric sensitivity and accommodation are unknown (2), compliance and gastric sensitivity to distention significantly The aim of this study is to evaluate the effect of Itopride, compared to compared to placebo. Domperidone, a dopamine D2 receptor antagonist, on the sensitivity to gastric * Placebo balloon -

4 Supplementary File

Supplemental Material for High-throughput screening discovers anti-fibrotic properties of Haloperidol by hindering myofibroblast activation Michael Rehman1, Simone Vodret1, Luca Braga2, Corrado Guarnaccia3, Fulvio Celsi4, Giulia Rossetti5, Valentina Martinelli2, Tiziana Battini1, Carlin Long2, Kristina Vukusic1, Tea Kocijan1, Chiara Collesi2,6, Nadja Ring1, Natasa Skoko3, Mauro Giacca2,6, Giannino Del Sal7,8, Marco Confalonieri6, Marcello Raspa9, Alessandro Marcello10, Michael P. Myers11, Sergio Crovella3, Paolo Carloni5, Serena Zacchigna1,6 1Cardiovascular Biology, 2Molecular Medicine, 3Biotechnology Development, 10Molecular Virology, and 11Protein Networks Laboratories, International Centre for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (ICGEB), Padriciano, 34149, Trieste, Italy 4Institute for Maternal and Child Health, IRCCS "Burlo Garofolo", Trieste, Italy 5Computational Biomedicine Section, Institute of Advanced Simulation IAS-5 and Institute of Neuroscience and Medicine INM-9, Forschungszentrum Jülich GmbH, 52425, Jülich, Germany 6Department of Medical, Surgical and Health Sciences, University of Trieste, 34149 Trieste, Italy 7National Laboratory CIB, Area Science Park Padriciano, Trieste, 34149, Italy 8Department of Life Sciences, University of Trieste, Trieste, 34127, Italy 9Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (IBCN), CNR-Campus International Development (EMMA- INFRAFRONTIER-IMPC), Rome, Italy This PDF file includes: Supplementary Methods Supplementary References Supplementary Figures with legends 1 – 18 Supplementary Tables with legends 1 – 5 Supplementary Movie legends 1, 2 Supplementary Methods Cell culture Primary murine fibroblasts were isolated from skin, lung, kidney and hearts of adult CD1, C57BL/6 or aSMA-RFP/COLL-EGFP mice (1) by mechanical and enzymatic tissue digestion. Briefly, tissue was chopped in small chunks that were digested using a mixture of enzymes (Miltenyi Biotec, 130- 098-305) for 1 hour at 37°C with mechanical dissociation followed by filtration through a 70 µm cell strainer and centrifugation. -

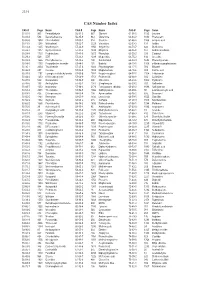

CAS Number Index

2334 CAS Number Index CAS # Page Name CAS # Page Name CAS # Page Name 50-00-0 905 Formaldehyde 56-81-5 967 Glycerol 61-90-5 1135 Leucine 50-02-2 596 Dexamethasone 56-85-9 963 Glutamine 62-44-2 1640 Phenacetin 50-06-6 1654 Phenobarbital 57-00-1 514 Creatine 62-46-4 1166 α-Lipoic acid 50-11-3 1288 Metharbital 57-22-7 2229 Vincristine 62-53-3 131 Aniline 50-12-4 1245 Mephenytoin 57-24-9 1950 Strychnine 62-73-7 626 Dichlorvos 50-23-7 1017 Hydrocortisone 57-27-2 1428 Morphine 63-05-8 127 Androstenedione 50-24-8 1739 Prednisolone 57-41-0 1672 Phenytoin 63-25-2 335 Carbaryl 50-29-3 569 DDT 57-42-1 1239 Meperidine 63-75-2 142 Arecoline 50-33-9 1666 Phenylbutazone 57-43-2 108 Amobarbital 64-04-0 1648 Phenethylamine 50-34-0 1770 Propantheline bromide 57-44-3 191 Barbital 64-13-1 1308 p-Methoxyamphetamine 50-35-1 2054 Thalidomide 57-47-6 1683 Physostigmine 64-17-5 784 Ethanol 50-36-2 497 Cocaine 57-53-4 1249 Meprobamate 64-18-6 909 Formic acid 50-37-3 1197 Lysergic acid diethylamide 57-55-6 1782 Propylene glycol 64-77-7 2104 Tolbutamide 50-44-2 1253 6-Mercaptopurine 57-66-9 1751 Probenecid 64-86-8 506 Colchicine 50-47-5 589 Desipramine 57-74-9 398 Chlordane 65-23-6 1802 Pyridoxine 50-48-6 103 Amitriptyline 57-92-1 1947 Streptomycin 65-29-2 931 Gallamine 50-49-7 1053 Imipramine 57-94-3 2179 Tubocurarine chloride 65-45-2 1888 Salicylamide 50-52-2 2071 Thioridazine 57-96-5 1966 Sulfinpyrazone 65-49-6 98 p-Aminosalicylic acid 50-53-3 426 Chlorpromazine 58-00-4 138 Apomorphine 66-76-2 632 Dicumarol 50-55-5 1841 Reserpine 58-05-9 1136 Leucovorin 66-79-5 -

Gastroparesis: 2014

GASTROINTESTINAL MOTILITY AND FUNCTIONAL BOWEL DISORDERS, SERIES #1 Richard W. McCallum, MD, FACP, FRACP (Aust), FACG Status of Pharmacologic Management of Gastroparesis: 2014 Richard W. McCallum Joseph Sunny, Jr. Gastroparesis is characterized by delayed gastric emptying without mechanical obstruction of the gastric outlet or small intestine. The main etiologies are diabetes, idiopathic and post- gastric and esophageal surgical settings. The management of gastroparesis is challenging due to a limited number of medications and patients often have symptoms, which are refractory to available medications. This article reviews current treatment options for gastroparesis including adverse events and limitations as well as future directions in pharmacologic research. INTRODUCTION astroparesis is a syndrome characterized by documented gastroparesis are increasing.2 Physicians delayed emptying of gastric contents without have both medical and surgical approaches for these Gmechanical obstruction of the stomach, pylorus or patients (See Figure 1). Medical therapy includes both small bowel. Patients can present with nausea, vomiting, prokinetics and antiemetics (See Table 1 and Table 2). postprandial fullness, early satiety, pressure, fullness The gastroparesis population will grow as diabetes and abdominal distension. In addition, abdominal pain increases and new therapies will be required. What located in the epigastrium, and distinguished from the do we know about the size of the gastroparetic term discomfort, is increasingly being recognized population? According to a study from the Mayo Clinic as an important symptom. The main etiologies of group surveying Olmsted County in Minnesota, the gastroparesis are diabetes, idiopathic, and post gastric risk of gastroparesis in Type 1 diabetes mellitus was and esophageal surgeries.1 Hospitalizations from significantly greater than for Type 2. -

Itopride : a Novel Prokinetic Agent Seema Gupta, V

JK SCIENCE DRUG REVIEW Itopride : A Novel Prokinetic Agent Seema Gupta, V. Kapoor, B. Kapoor Non-ulcer dyspepsia (NUD), gastro-esophageal reflux back(5). This drug was first developed by Hokuriku disease (GERD), gastritis, diabetic gastroparesis and Seiyaker Co. Ltd. and has been marketed in Japan since functional dyspepsia are commonly encountered Sept. 1995 (6). disorders of gastric motility in clinical practice. Chemistry Prokinetic drugs such as metoclopramide, domperidone, Chemically it is N-[P-[2-[dimethyl cisapride, mosapride etc. are the mainstay of therapy in amino]ethoxyl]benzyl] veratramide hydrochloride. Its these disorders. These drugs are used to relieve symptoms molecular formula is C20H26O4. HCl (6).The chemical such as nausea, vomiting, bloating, belching, heartburn, structure of Itopride hydrochloride is depicted below: epigastric discomfort etc. Prokinetic drugs act by promoting gastric motility, increase gastric emptying, prevent the retention and reflux of gastric contents and thus provide symptomatic relief (1). All the drugs in this group are efficacious with Mechanism of action modest prokinetic activity but the matter of major Itopride has anticholinesterase (AchE) activity as well concern is their side effect profile. The main side effects as dopamine D2 receptor antagonistic activity and is being of metoclopramide are extra pyramidal such as dystonic used for the symptomatic treatment of various reactions and domperidone, though is devoid of extra- gastrointestinal motility disorders (7, 8). pyramidal effects but is associated with galactorrhoea It is well established that M3 receptors exist on the or gynaecomastia (2). Cisapride has the potential to cause smooth muscle layer throughout the gut and acetylcholine QT prolongation on ECG, thus predisposing to cardiac (ACh) released from enteric nerve endings stimulates the contraction of smooth muscle through M receptors arrhythmias and its use has been restricted by the US 3 (9). -

Patent Application Publication ( 10 ) Pub . No . : US 2019 / 0192440 A1

US 20190192440A1 (19 ) United States (12 ) Patent Application Publication ( 10) Pub . No. : US 2019 /0192440 A1 LI (43 ) Pub . Date : Jun . 27 , 2019 ( 54 ) ORAL DRUG DOSAGE FORM COMPRISING Publication Classification DRUG IN THE FORM OF NANOPARTICLES (51 ) Int . CI. A61K 9 / 20 (2006 .01 ) ( 71 ) Applicant: Triastek , Inc. , Nanjing ( CN ) A61K 9 /00 ( 2006 . 01) A61K 31/ 192 ( 2006 .01 ) (72 ) Inventor : Xiaoling LI , Dublin , CA (US ) A61K 9 / 24 ( 2006 .01 ) ( 52 ) U . S . CI. ( 21 ) Appl. No. : 16 /289 ,499 CPC . .. .. A61K 9 /2031 (2013 . 01 ) ; A61K 9 /0065 ( 22 ) Filed : Feb . 28 , 2019 (2013 .01 ) ; A61K 9 / 209 ( 2013 .01 ) ; A61K 9 /2027 ( 2013 .01 ) ; A61K 31/ 192 ( 2013. 01 ) ; Related U . S . Application Data A61K 9 /2072 ( 2013 .01 ) (63 ) Continuation of application No. 16 /028 ,305 , filed on Jul. 5 , 2018 , now Pat . No . 10 , 258 ,575 , which is a (57 ) ABSTRACT continuation of application No . 15 / 173 ,596 , filed on The present disclosure provides a stable solid pharmaceuti Jun . 3 , 2016 . cal dosage form for oral administration . The dosage form (60 ) Provisional application No . 62 /313 ,092 , filed on Mar. includes a substrate that forms at least one compartment and 24 , 2016 , provisional application No . 62 / 296 , 087 , a drug content loaded into the compartment. The dosage filed on Feb . 17 , 2016 , provisional application No . form is so designed that the active pharmaceutical ingredient 62 / 170, 645 , filed on Jun . 3 , 2015 . of the drug content is released in a controlled manner. Patent Application Publication Jun . 27 , 2019 Sheet 1 of 20 US 2019 /0192440 A1 FIG . -

Conductometric Determination of Tiemonium Methylsulfate, Alizapride Hydrochloride, Trimebutine Maleate Using Rose Bengal, Ammonium Reineckate and Phosphotungstic Acid

Indian Available online at Journal of Advances in www.ijacskros.com Chemical Science Indian Journal of Advances in Chemical Science 4(2) (2016) 149-159 Conductometric Determination of Tiemonium Methylsulfate, Alizapride Hydrochloride, Trimebutine Maleate using Rose Bengal, Ammonium Reineckate and Phosphotungstic Acid M. Ayad, M. El-Balkiny, M. Hosny*, Y. Metias Department of Analytical Chemistry, Faculty of Pharmacy, Zagazig University, Zagazig, 44519, Egypt. Received 03rd January 2016; Revised 02nd March 2016; Accepted 11th March 2016 ABSTRACT Simple, cost-effective, accurate and easily applicable conductometric titration was applied using three different ion-pairing reagents; rose bengal, ammonium reineckate, and phosphotungstic acid represented as method A, B and C, respectively, for determination of tiemonium methylsulfate (TIM) and alizapride hydrochloride (AL). Method A, B had been described for the determination of trimebutine maleate (TRM). The proposed methods have been successfully employed for the determination of pure and pharmaceutical dosage forms with studying the effect of common pharmaceutical excipients which did not interfere with the assay procedure. Optimized conditions including temperature, solvent, reagent concentration, and molar ratio were studied. Beer’s law was obeyed in the concentration ranges of (1-20), (1.5-10), (1-12) mg/50 ml of TIM, (1-17), (1-10), (0.6-12) mg/50 ml of AL for Method A, B and C, respectively, where (1-17), (1.5-10) mg/50 ml of TRM for Method A and B, respectively. Results of analysis were validated statistically by recovery studies. Key words: Tiemonium, Alizapride, Trimebutine, Conductometry. 1. INTRODUCTION of AL and its degradation products in bulk drug and Tiemonium methylsulfate or tiemoniummetilsulfate pharmaceutical formulations [9]. -

Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization

No. 31874 Multilateral Marrakesh Agreement establishing the World Trade Organ ization (with final act, annexes and protocol). Concluded at Marrakesh on 15 April 1994 Authentic texts: English, French and Spanish. Registered by the Director-General of the World Trade Organization, acting on behalf of the Parties, on 1 June 1995. Multilat ral Accord de Marrakech instituant l©Organisation mondiale du commerce (avec acte final, annexes et protocole). Conclu Marrakech le 15 avril 1994 Textes authentiques : anglais, français et espagnol. Enregistré par le Directeur général de l'Organisation mondiale du com merce, agissant au nom des Parties, le 1er juin 1995. Vol. 1867, 1-31874 4_________United Nations — Treaty Series • Nations Unies — Recueil des Traités 1995 Table of contents Table des matières Indice [Volume 1867] FINAL ACT EMBODYING THE RESULTS OF THE URUGUAY ROUND OF MULTILATERAL TRADE NEGOTIATIONS ACTE FINAL REPRENANT LES RESULTATS DES NEGOCIATIONS COMMERCIALES MULTILATERALES DU CYCLE D©URUGUAY ACTA FINAL EN QUE SE INCORPOR N LOS RESULTADOS DE LA RONDA URUGUAY DE NEGOCIACIONES COMERCIALES MULTILATERALES SIGNATURES - SIGNATURES - FIRMAS MINISTERIAL DECISIONS, DECLARATIONS AND UNDERSTANDING DECISIONS, DECLARATIONS ET MEMORANDUM D©ACCORD MINISTERIELS DECISIONES, DECLARACIONES Y ENTEND MIENTO MINISTERIALES MARRAKESH AGREEMENT ESTABLISHING THE WORLD TRADE ORGANIZATION ACCORD DE MARRAKECH INSTITUANT L©ORGANISATION MONDIALE DU COMMERCE ACUERDO DE MARRAKECH POR EL QUE SE ESTABLECE LA ORGANIZACI N MUND1AL DEL COMERCIO ANNEX 1 ANNEXE 1 ANEXO 1 ANNEX -

REVIEW Genotoxic and Carcinogenic Effects of Gastrointestinal Drugs

Mutagenesis vol. 25 no. 4 pp. 315–326, 2010 doi:10.1093/mutage/geq025 Advance Access Publication 17 May 2010 REVIEW Genotoxic and carcinogenic effects of gastrointestinal drugs Giovanni Brambilla*, Francesca Mattioli and a further in vivo test using a tissue other than the bone marrow/ Antonietta Martelli peripheral blood should be done. Guidelines for carcinogenic- Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Clinical Pharmacology and ity testing of pharmaceuticals (4,5) indicate that a long-term Toxicology, University of Genoa, Viale Benedetto XV 2, I-16132 Genoa, Italy carcinogenicity study plus a short- or medium-term in vivo system should be performed for all pharmaceuticals whose expected clinical use is continuous for at least 6 months as *To whom correspondence should be addressed. Tel: +39 010 353 8800; well as for pharmaceuticals used frequently in an intermittent Fax: þ39 010 353 8232; Email: [email protected] manner in the treatment of chronic recurrent conditions. In the Received on January 28, 2010; revised on March 23, 2010; absence of clear evidence favouring one species, the rat should accepted on April 13, 2010 be selected. In long-term carcinogenicity assays, the highest This review provides a compendium of retrievable results dose should be at least .25-fold, on a milligram per square of genotoxicity and carcinogenicity assays performed on meter basis, than the maximum recommended human daily marketed gastrointestinal drugs. Of the 71 drugs consid- dose or represent a 25-fold ratio of rodent to human area under ered, 38 (53.5%) do not have retrievable data, whereas the curve. The maximum tolerated dose (MTD) or a limit dose the other 33 (46.5%) have at least one genotoxicity or of 2000 mg/kg can be used as alternatives. -

Prokinetics for the Treatment of Functional Dyspepsia: Bayesian

Yang et al. BMC Gastroenterology (2017) 17:83 DOI 10.1186/s12876-017-0639-0 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Prokinetics for the treatment of functional dyspepsia: Bayesian network meta-analysis Young Joo Yang, Chang Seok Bang* , Gwang Ho Baik, Tae Young Park, Suk Pyo Shin, Ki Tae Suk and Dong Joon Kim Abstract Background: Controversies persist regarding the effect of prokinetics for the treatment of functional dyspepsia (FD). This study aimed to assess the comparative efficacy of prokinetic agents for the treatment of FD. Methods: Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of prokinetics for the treatment of FD were identified from core databases. Symptom response rates were extracted and analyzed using odds ratios (ORs). A Bayesian network meta- analysis was performed using the Markov chain Monte Carlo method in WinBUGS and NetMetaXL. Results: In total, 25 RCTs, which included 4473 patients with FD who were treated with 6 different prokinetics or placebo, were identified and analyzed. Metoclopramide showed the best surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) probability (92.5%), followed by trimebutine (74.5%) and mosapride (63.3%). However, the therapeutic efficacy of metoclopramide was not significantly different from that of trimebutine (OR:1.32, 95% credible interval: 0.27–6.06), mosapride (OR: 1.99, 95% credible interval: 0.87–4.72), or domperidone (OR: 2.04, 95% credible interval: 0.92–4.60). Metoclopramide showed better efficacy than itopride (OR: 2.79, 95% credible interval: 1. 29–6.21) and acotiamide (OR: 3.07, 95% credible interval: 1.43–6.75). Domperidone (SUCRA probability 62.9%) showed better efficacy than itopride (OR: 1.37, 95% credible interval: 1.07–1.77) and acotiamide (OR: 1.51, 95% credible interval: 1.04–2.18). -

Poison Act 1952

LAWS OF MALAYSIA _____________ ONLINE VERSION OF UPDATED TEXT OF REPRINT _____________ Act 366 POISONS ACT 1952 As at 1 February 2019 2 POISONS ACT 1952 First enacted … … … … 1952 (Ord. No. 29 of 1952) Revised … … … … 1989 (Act 366 w.e.f. 13 April 1989) Latest amendment made by P.U. (A) 8/2019 which came into operation on … … 10 January 2019 PREVIOUS REPRINTS First Reprint ... ... ... ... ... 2001 Second Reprint ... ... ... ... ... 2006 3 LAWS OF MALAYSIA Act 366 POISONS ACT 1952 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS Section 1. Short title and application 2. Interpretation 3. Establishment of Poisons Board 4. Proceedings of Board 5. Powers of Board to regulate proceedings 6. Power of Minister to amend Poisons List 7. Application of the Act 8. Control of imports of poisons 9. Packaging, labelling and storing of poisons 10. Transport of poisons 11. Control of manufacture of preparations containing poison 12. Control of compounding of poisons for use in medical treatment 13. Possession for sale of poison and sale of poison in contravention of this Act an offence 14. Control of acetylating substances 15. Sale of poisons by wholesale 16. Sale of poisons by retail 17. Prohibition of sale to persons under 18 18. Restriction on the sale of Part I poisons generally 19. Supply of poisons for the purpose of treatment by professional men 20. Group A Poisons 21. Group B Poisons 4 Laws of Malaysia ACT 366 Section 22. Group C Poisons 23. Group D Poisons 24. Prescription book 25. Sale of Part II Poisons 26. Licences 27. Register of licences 28. Annual list to be published 29.