The Jewish Soldier's Red Star

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Adaptation Group for Middle-Aged Clients from the Former Soviet Union

AN ADAPTATION GROUP FOR MIDDLE-AGED CLIENTS FROM THE FORMER SOVIET UNION ADELE NIKOLSKY Coordinator of the Russian Program, Madeleine Borg Community Services Clinic of the Jewish Board of Family and Children's Services, Brooklyn, New York Emigres from the former Soviet Union are able to participate in group therapy if the group process is not initiated by the leader but is a spontaneous byproduct of some more emotionally neutral process, such as lectures or group activities. The goal of the group described in this article was to help its middle-aged members break out of their isolation and adapt to their new country. To reach this goal, several modalities were applied in tum and together—lectures, regular group process, cultural activities, and finally transi tion to a self-help group. This wasn Y, as it might seem, another lost crisis after emigration. These women's generation. This W(3S the only generation of ability to share was limited ottiy to informa Russians that found itself. tion on community resources they all were Joseph Brodsky interested in, such as legal aid, child care Less Than One (1986, p. 29) facilities, and the like. On the other hand, there has been a posi t present, mental health clinics serving tive experience in a group for battered A:lients from the former Soviet Union women from the FSU that was run by (FSU) have to cope with often overwhelm NY ANA. However, all these group mem ing numbers of middle-aged immigrants bers had had an opportunity to develop a presenting with symptoms of high anxiety good rapport and trustfiil relationship with and depression. -

Trade Marks Inter Parte Decision O/526/20

O-526-20 TRADE MARKS ACT 1994 IN THE MATTER OF APPLICATION NO. 3389020 BY EFE TEMIZEL TO REGISTER: AS A TRADE MARK IN CLASS 25 AND IN THE MATTER OF OPPOSITION THERETO UNDER NO. 417707 BY HANES INNERWEAR AUSTRALIA PTY LTD Background & Pleadings 1. On 2 April 2019, Efe Temizel (“the applicant”) applied to register the above trade mark for a variety of goods in class 25, laid out in their entirety at annex 1 of this decision. The application was published for opposition purposes on 14 June 2019. 2. On 16 September 2019, the application was opposed in full by Hanes Innerwear Australia Pty Ltd (“the opponent”). The opposition is based upon section 5(2)(b) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 (“the Act”), in relation to which the opponent relies upon the marks laid out below and all goods for which each is registered: United Kingdom Trade Mark (“UKTM”) 3154319 BOND Class 25: Clothing; footwear; headgear; swimwear; sportswear; leisurewear. Filed on 11 March 2016 Registered on 30 December 2016 International Registration (“IR”) 1377504 Class 25: Clothing; footwear; headgear. Designated the UK on 1 November 2017 Granted protection in the UK on 3 May 2018 IR 801821 Class 25: Clothing, footwear and headgear. Designated the UK on 9 November 2017 Granted protection in the UK on 24 May 2018 1 European Union Trade Mark (“EUTM”) 17459371 BONDS Class 25: Clothing, footwear, headgear. Filed on 10 November 2017 Registered on 8 May 2018 3. In its Notice of Opposition, the opponent submits that the similarity between the respective trade marks, coupled with the similarity, or identity, between the respective goods would result in a likelihood of confusion on the part of the relevant public. -

A Life on the Left: Moritz Mebel’S Journey Through the Twentieth Century

Swarthmore College Works History Faculty Works History 4-1-2007 A Life On The Left: Moritz Mebel’s Journey Through The Twentieth Century Robert Weinberg Swarthmore College, [email protected] Marion J. Faber , translator Swarthmore College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-history Part of the German Language and Literature Commons, and the History Commons Let us know how access to these works benefits ouy Recommended Citation Robert Weinberg and Marion J. Faber , translator. (2007). "A Life On The Left: Moritz Mebel’s Journey Through The Twentieth Century". The Carl Beck Papers In Russian And East European Studies. Issue 1805. https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-history/533 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Carl Beck Papers Robert Weinberg, Editor in Russian & Marion Faber, Translator East European Studies Number 1805 A Life on the Left: Moritz Mebel’s Journey Through the Twentieth Century Moritz Mebel and his wife, Sonja The Carl Beck Papers in Russian & East European Studies Number 1805 Robert Weinberg, Editor Marion Faber, Translator A Life on the Left: Moritz Mebel’s Journey Through the Twentieth Century Marion Faber is Scheuer Family Professor of Humanities at Swarthmore College. Her previous translations include Sarah Kirsch’s The Panther Woman (1989) and Friedrich Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil (1998). -

Penalties and Rewards in Soviet Law

Washington Law Review Volume 25 Number 2 5-1-1950 Penalties and Rewards in Soviet Law George C. Guins Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wlr Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons Recommended Citation George C. Guins, Far Eastern Section, Penalties and Rewards in Soviet Law, 25 Wash. L. Rev. & St. B.J. 206 (1950). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wlr/vol25/iss2/6 This Far Eastern Section is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at UW Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington Law Review by an authorized editor of UW Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FAR EASTERN SECTION PENALTIES AND REWARDS IN SOVIET LAW GEORGE C. GUINS* T HE SOVIET system and practice of penalties and rewards have sev- eral peculiarities which are undoubtedly bound up with Soviet socialism. Long before the Revolution of 1917, the eminent Russian scholar L. J. Petrazicki pointed out that with a transition to socialism there would be greater emphasis on the system of compulsion and rewards.' When the government becomes the supreme monopolist and arbitrator of all earnings and prices, when the livelihood of all its citizens is placed in direct dependence on the state, the stimuli of acquisition, gain, and risk lose their power. The incentive to work is derived from disin- terested devotion to national and humanitarian causes, or from antici- pation of favors from the powers that be. Lofty ideals and altruistic psychological motives are, however, not common among the masses. -

”Shoes”: a Componential Analysis of Meaning

Vol. 15 No.1 – April 2015 A Look at the World through a Word ”Shoes”: A Componential Analysis of Meaning Miftahush Shalihah [email protected]. English Language Studies, Sanata Dharma University Abstract Meanings are related to language functions. To comprehend how the meanings of a word are various, conducting componential analysis is necessary to do. A word can share similar features to their synonymous words. To reach the previous goal, componential analysis enables us to find out how words are used in their contexts and what features those words are made up. “Shoes” is a word which has many synonyms as this kind of outfit has developed in terms of its shape, which is obviously seen. From the observation done in this research, there are 26 kinds of shoes with 36 distinctive features. The types of shoes found are boots, brogues, cleats, clogs, espadrilles, flip-flops, galoshes, heels, kamiks, loafers, Mary Janes, moccasins, mules, oxfords, pumps, rollerblades, sandals, skates, slides, sling-backs, slippers, sneakers, swim fins, valenki, waders and wedge. The distinctive features of the word “shoes” are based on the heels, heels shape, gender, the types of the toes, the occasions to wear the footwear, the place to wear the footwear, the material, the accessories of the footwear, the model of the back of the shoes and the cut of the shoes. Keywords: shoes, meanings, features Introduction analyzed and described through its semantics components which help to define differential There are many different ways to deal lexical relations, grammatical and syntactic with the problem of meaning. It is because processes. -

Russian Museums Visit More Than 80 Million Visitors, 1/3 of Who Are Visitors Under 18

Moscow 4 There are more than 3000 museums (and about 72 000 museum workers) in Russian Moscow region 92 Federation, not including school and company museums. Every year Russian museums visit more than 80 million visitors, 1/3 of who are visitors under 18 There are about 650 individual and institutional members in ICOM Russia. During two last St. Petersburg 117 years ICOM Russia membership was rapidly increasing more than 20% (or about 100 new members) a year Northwestern region 160 You will find the information aboutICOM Russia members in this book. All members (individual and institutional) are divided in two big groups – Museums which are institutional members of ICOM or are represented by individual members and Organizations. All the museums in this book are distributed by regional principle. Organizations are structured in profile groups Central region 192 Volga river region 224 Many thanks to all the museums who offered their help and assistance in the making of this collection South of Russia 258 Special thanks to Urals 270 Museum creation and consulting Culture heritage security in Russia with 3M(tm)Novec(tm)1230 Siberia and Far East 284 © ICOM Russia, 2012 Organizations 322 © K. Novokhatko, A. Gnedovsky, N. Kazantseva, O. Guzewska – compiling, translation, editing, 2012 [email protected] www.icom.org.ru © Leo Tolstoy museum-estate “Yasnaya Polyana”, design, 2012 Moscow MOSCOW A. N. SCRiAbiN MEMORiAl Capital of Russia. Major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation center of Russia and the continent MUSEUM Highlights: First reference to Moscow dates from 1147 when Moscow was already a pretty big town. -

The Soviet Critique of a Liberator's

THE SOVIET CRITIQUE OF A LIBERATOR’S ART AND A POET’S OUTCRY: ZINOVII TOLKACHEV, PAVEL ANTOKOL’SKII AND THE ANTI-COSMOPOLITAN PERSECUTIONS OF THE LATE STALINIST PERIOD by ERIC D. BENJAMINSON A THESIS Presented to the Department of History and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts March 2018 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Eric D. Benjaminson Title: The Soviet Critique of a Liberator’s Art and a Poet’s Outcry: Zinovii Tolkachev, Pavel Antokol’skii and the Anti-Cosmopolitan Persecutions of the Late Stalinist Period This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of History by: Julie Hessler Chairperson John McCole Member David Frank Member and Sara D. Hodges Interim Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded: March 2018 ii © 2018 Eric D. Benjaminson iii THESIS ABSTRACT Eric D. Benjaminson Master of Arts Department of History March 2018 Title: The Soviet Critique of a Liberator’s Art and a Poet’s Outcry: Zinovii Tolkachev, Pavel Antokol’skii and the Anti-Cosmopolitan Persecutions of the Late Stalinist Period This thesis investigates Stalin’s post-WW2 anti-cosmopolitan campaign by comparing the lives of two Soviet-Jewish artists. Zinovii Tolkachev was a Ukrainian artist and Pavel Antokol’skii a Moscow poetry professor. Tolkachev drew both Jewish and Socialist themes, while Antokol’skii created no Jewish motifs until his son was killed in combat and he encountered Nazi concentration camps; Tolkachev was at the liberation of Majdanek and Auschwitz. -

When Victims Rule

1 24 JEWISH INFLUENCE IN THE MASS MEDIA, Part II In 1985 Laurence Tisch, Chairman of the Board of New York University, former President of the Greater New York United Jewish Appeal, an active supporter of Israel, and a man of many other roles, started buying stock in the CBStelevision network through his company, the Loews Corporation. The Tisch family, worth an estimated 4 billion dollars, has major interests in hotels, an insurance company, Bulova, movie theatres, and Loliards, the nation's fourth largest tobacco company (Kent, Newport, True cigarettes). Brother Andrew Tisch has served as a Vice-President for the UJA-Federation, and as a member of the United Jewish Appeal national youth leadership cabinet, the American Jewish Committee, and the American Israel Political Action Committee, among other Jewish organizations. By September of 1986 Tisch's company owned 25% of the stock of CBS and he became the company's president. And Tisch -- now the most powerful man at CBS -- had strong feelings about television, Jews, and Israel. The CBS news department began to live in fear of being compromised by their boss -- overtly, or, more likely, by intimidation towards self-censorship -- concerning these issues. "There have been rumors in New York for years," says J. J. Goldberg, "that Tisch took over CBS in 1986 at least partly out of a desire to do something about media bias against Israel." [GOLDBERG, p. 297] The powerful President of a major American television network dare not publicize his own active bias in favor of another country, of course. That would look bad, going against the grain of the democratic traditions, free speech, and a presumed "fair" mass media. -

Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Intelligence

Russia • Military / Security Historical Dictionaries of Intelligence and Counterintelligence, No. 5 PRINGLE At its peak, the KGB (Komitet Gosudarstvennoy Bezopasnosti) was the largest HISTORICAL secret police and espionage organization in the world. It became so influential DICTIONARY OF in Soviet politics that several of its directors moved on to become premiers of the Soviet Union. In fact, Russian president Vladimir V. Putin is a former head of the KGB. The GRU (Glavnoe Razvedvitelnoe Upravleniye) is the principal intelligence unit of the Russian armed forces, having been established in 1920 by Leon Trotsky during the Russian civil war. It was the first subordinate to the KGB, and although the KGB broke up with the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the GRU remains intact, cohesive, highly efficient, and with far greater resources than its civilian counterparts. & The KGB and GRU are just two of the many Russian and Soviet intelli- gence agencies covered in Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Intelligence. Through a list of acronyms and abbreviations, a chronology, an introductory HISTORICAL DICTIONARY OF essay, a bibliography, and hundreds of cross-referenced dictionary entries, a clear picture of this subject is presented. Entries also cover Russian and Soviet leaders, leading intelligence and security officers, the Lenin and Stalin purges, the gulag, and noted espionage cases. INTELLIGENCE Robert W. Pringle is a former foreign service officer and intelligence analyst RUSSIAN with a lifelong interest in Russian security. He has served as a diplomat and intelligence professional in Africa, the former Soviet Union, and Eastern Europe. For orders and information please contact the publisher && SOVIET Scarecrow Press, Inc. -

Lelov: Cultural Memory and a Jewish Town in Poland. Investigating the Identity and History of an Ultra - Orthodox Society

Lelov: cultural memory and a Jewish town in Poland. Investigating the identity and history of an ultra - orthodox society. Item Type Thesis Authors Morawska, Lucja Rights <a rel="license" href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/"><img alt="Creative Commons License" style="border-width:0" src="http://i.creativecommons.org/l/by- nc-nd/3.0/88x31.png" /></a><br />The University of Bradford theses are licenced under a <a rel="license" href="http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/">Creative Commons Licence</a>. Download date 03/10/2021 19:09:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10454/7827 University of Bradford eThesis This thesis is hosted in Bradford Scholars – The University of Bradford Open Access repository. Visit the repository for full metadata or to contact the repository team © University of Bradford. This work is licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence. Lelov: cultural memory and a Jewish town in Poland. Investigating the identity and history of an ultra - orthodox society. Lucja MORAWSKA Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Social and International Studies University of Bradford 2012 i Lucja Morawska Lelov: cultural memory and a Jewish town in Poland. Investigating the identity and history of an ultra - orthodox society. Key words: Chasidism, Jewish History in Eastern Europe, Biederman family, Chasidic pilgrimage, Poland, Lelov Abstract. Lelov, an otherwise quiet village about fifty miles south of Cracow (Poland), is where Rebbe Dovid (David) Biederman founder of the Lelov ultra-orthodox (Chasidic) Jewish group, - is buried. -

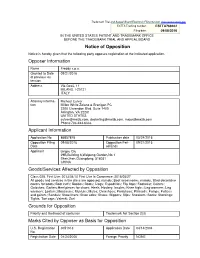

Notice of Opposition Opposer Information Applicant Information

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Electronic Filing System. http://estta.uspto.gov ESTTA Tracking number: ESTTA769402 Filing date: 09/08/2016 IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Notice of Opposition Notice is hereby given that the following party opposes registration of the indicated application. Opposer Information Name Freddy s.p.a. Granted to Date 09/21/2016 of previous ex- tension Address Via Gesù, 11 MILANO, I-20121 ITALY Attorney informa- Michael Culver tion Millen White Zelano & Branigan PC 2200 Clarendon Blvd. Suite 1400 Arlington, VA 22201 UNITED STATES [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Phone:703-243-6333 Applicant Information Application No 86857876 Publication date 05/24/2016 Opposition Filing 09/08/2016 Opposition Peri- 09/21/2016 Date od Ends Applicant Lingsu Qiu 29B,Building 6,Weipeng Garden,No.1 Shenzhen,Guangdong, 518031 CHINA Goods/Services Affected by Opposition Class 025. First Use: 2013/04/10 First Use In Commerce: 2015/05/27 All goods and services in the class are opposed, namely: Boot accessories, namely, fitted decorative covers for boots; Boot cuffs; Booties; Boots; Clogs; Espadrilles; Flip flops; Footwear; Gaiters; Galoshes; Garters;Heel pieces for shoes; Heels; Hosiery; Insoles; Knee highs; Leg-warmers; Leg warmers; Loafers; Moccasins; Mukluks; Mules; Overshoes; Pantyhose; Plimsolls; Pumps; Puttees and gaiters; Sandals; Shoe liners; Shoe soles; Shoes; Slippers; Slips; Sneakers; Socks; Stockings; Tights; Toe caps; Valenki; Zori Grounds for Opposition Priority and likelihood of confusion Trademark Act Section 2(d) Marks Cited by Opposer as Basis for Opposition U.S. -

ISSN 1410-5691 Vol. 15 – No. 1 / April 2015

Vol. 15 – No. 1 / April 2015 ISSN 1410-5691 Paulus Sarwoto Literary Theory in Indonesian English Department: between Truth and Meaning I Wayan Mulyawan Three Dimensional Aspects of the Major Character in Oscar Wilde’s Vera Dwi Nita Febriyani Assimilation, Reduction and Elision Reflected in the Selected Song Lyrics of Avenged Sevenfold Adi Renaldi & Dewi Widyastuti The Inauthenticity of the Main Characters as an Impact of Totalitarian System Seen in George Orwell’s 1984 Tia Xenia Vowel Change Found in Geoffrey Chaucer’s The House of Fame: Great Vowel Shift Laurencya Hellene Larasati Ruruk & Ni Luh Putu Rosiandani The Resistance of Women towards Sexual Terrorism in Eve Ensler’s The Vagina Monologues Adria Vitalya Gemilang Another Side of Indonesian History of Communism in Leila S. Chudori’s Pulang Alwi Atma Ardhana & Elisa Dwi Wardani The Hospital as an Ideological State Apparatus and Disciplinary Agent as Seen through the Main Character in Kenzaburo Oe’s A Personal Matter Deta Maria Sri Darta Department of English Letters Levỳ’s Minimax Strategy in Translating a Popular Article: Universitas Sanata Dharma Theory in Practice Jl. Affandi, Mrican, Miftahush Shalihah Yogyakarta 55281 A Look at the World through a Word ”Shoes”: (Mrican, PO BOX 29, Yogyakarta A Componential Analysis of Meaning 55002) Hermawan & Adventina Putranti (0274) 513301, 515352 C.S. Lewis’ Use of Symbol to Express Christian Concepts, ext.1324 Stories, and Teaching as Seen in The Chronicles of Narnia: Fax. (0274) 562383 the Magician’s Nephew [email protected] Journal of Language and Literature Volume 15 Number 1 – April 2015 Executive Officer Editors Anna Fitriati, S.Pd., M.Mum Harris Hermansyah S., S.S., M.Hum.