Influence of Saka Scythian : an Ancient Art of Rajasthan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dileep Singh Chauhan

Dileep Singh Chauhan Born 1954, Rajasthan, India Received STATE AWARDS by Rajasthan Lalit kala Akademi in the years 1981/82/86/88. Received ALL INDIA AWARD by Rajasthan Lalit Kala Akademi in 1991. Participating in the state annual exhibitions and various other exhibitions organized by Rajasthan Lalit Kala Akademi, Jaipur since 1974-75. Takhman - 28 Group Exhibitions in Rajasthan and at major art centers in India since 1979. Exhibited in a number of group shows and in almost all the major All India Exhibitions including National Exhibition of Art, New Delhi. 1. Exhibited in The First Bharat Bhawan Biennial of Contemporary Indian Art, 1986. 2. ALL INDIA ART EXHIBITION organized by AIFACS, New Delhi, 1987. 3. Exhibition CONTEMPORARY ART OF RAJASTHAN, Jehangir Art Gallery Bombay, organized by RLKA, 1990. 4. CONTEMPORARY ART EXHIBITION OF RAJASTHAN at Kala Akademi - Panjim Goa, organized by RLKA, 1995. 5. CONTEMPORARY ART OF RAJASTHAN at Sirjana Contemporary Art Gallery, Kathmandu, organized by RLKA, 1996. 6. Exhibited in Colour of Rajasthan organized by RLKA and JKK, Jaipur, 1998. 7. Exhibited in GRAPHIC EXPRESSIONS Print Show 2000, presented by Cymroza Art Gallery, at Mumbai, Chennai, Calcutta, New Delhi. 8. REGIONAL ART EXHIBITION 2000-01 at Ravishankar Kala Bhawan, Ahmedabad, organized by Rashtriya Lalit Kala Kendra Lucknow. 9. Exhibited in WE13 Printmakers 2000-01, at Jaipur, New Delhi, Chandigarh, Bangalore and Ahmedabad. 10. Exhibited in THE DESERT AND BEYOND EXHIBITION, presented by The British Council, at The Queen's Gallery, New Delhi, 1999. 11. Exhibited in Contemporary Art of Rajasthan – chain exhibition by Jawahar Kala Kendra, Jaipur, Chandigarh, Patiala, 2003. -

Download Full Paper

RSU International Research Conference 2019 https://rsucon.rsu.ac.th/proceedings 26 April 2019 The Study of the History and the Characteristic of the Glorious Wall Paintings of Bundi Chitrasala Reetika Garg Department of Drawing & Painting, University of Rajasthan, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India E-mail: [email protected] ________________________________________________________________________________________________ Abstract The civilization of India is one of the most important events in the history of mankind. Wall paintings were a normal feature of ancient India. An unbroken stream of references to wall paintings is evidenced in the literary texts. Bundi is a town of Rajasthan, an Indian state, which is famous for its forts and fresco. There is a rich treasure trove of wall paintings of magnificent palace complexes of Bundi in Rajasthan. The chitrashala of Bundi fort is fully decorated with beautiful wall paintings. It has a variety of themes, both religious and secular. The walls also show a much wider range of subjects than is to be found in the miniatures. The traditional subjects were related to Ramayana, Krishna – leela, Shiv-Parvati and the lord Bramha, but the most striking impression is conveyed by more than thirty-six panels devoted to the paintings of Nayikas. The Chitrasala not only presents an astonishing world of people engaged in various amusements, religious beliefs, social customs etc. but it also presents a great tradition of Bundi style of painting. Keywords: Chitrasala, treasure, wall paintings, Nayikas, Ramayana, miniatures _______________________________________________________________________________________________ 1. Introduction India is unique in its art traditions. No country in the world has until now preserved its age-old traditions as vigorously and stead-fastly as India has done. -

Rajasthan Public Service Commission, Ajmer

RAJASTHAN PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION, AJMER SYLLABUS FOR SCREENING TEST FOR THE POST OF ASSISTANT TESTING OFFICER (GEOLOGY) FOR PUBLIC WORKS DEPARTMENT PART-A (General Knowledge of Rajasthan) History, Art, Culture, Literature and Heritage of Rajasthan:- Prehistoric Rajasthan: Harappan and chalcolithic settlements. Cultural Achievements of the Rulers of Rajasthan from Early Medieval period to British period. Political Resistance of Rajput Rulers: Sultanate, Mughal and other regional powers with special reference to Rawal Ratan Singh, Hammir Chauhan, Maharan Kumbha, Rao Maldev and Maharana Pratap. Commencement of Modernity in Rajasthan: Agents of social and political awakening. Peasant, Tribal and Praja Mandal movements. Process of Integration: The constructive contribution of rulers of princely states, various phases of integration. Performing Art of Rajasthan: Folk music, folk instruments and folk dances. Visual Art of Rajasthan: Schools of painting and architecture (temples, forts, palaces, Havelis and Baories (stepwells). Social Life in Rajasthan: Religious belief with reference to folk deities, fairs and festivals, customs and traditions, dresses and ornaments. Language and Literature of Rajasthan: Main dialects and related regions, famous authors of Rajasthani literature and their works. Geography of Rajasthan:- Physiographic Regions, Rivers and Lakes. Climate, Natural Vegetation, Soil types, Major Minerals and Energy Resources – Renewable and Non-renewable. Population – Growth, distribution and density. Production and Distribution of Major Crops, Major Irrigation Projects, Major Industries. Drought and Famines, Desertification, Environmental Problems. Economy of Rajasthan:- Characteristics of state economy. Agricultural Sector: Characteristics of agricultural sector in Rajasthan. Major Rabi and Kharif crops with special reference to oil seeds and spices. Irrigated area and trends. Health programmes of state government. -

Review of Research Impact Factor : 5.2331(Uif) Ugc Approved Journal No

Review Of ReseaRch impact factOR : 5.2331(Uif) UGc appROved JOURnal nO. 48514 issn: 2249-894X vOlUme - 7 | issUe - 9 | JUne - 2018 __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ INDIAN OLD MURAL PAINTINGS Kashinath D. W. Faculty, Department of Visual Art, Gulbarga University, Kalaburagi. ABSTRACT : Indian painting has a very long tradition and history in Indian art. The earliest Indian paintings were the rock paintings of pre-historic times, the petroglyphs as found in places like Bhimbetka rock shelters, some of the Stone Age rock paintings found among the Bhimbetka rock shelters are approximately 30,000 years old.[1] India's Buddhist literature is replete with examples of texts which describe palaces of the army and the aristocratic class embellished with paintings, but the paintings of the Ajanta Caves are the most significant of the few survivals. Smaller scale painting in manuscripts was probably also practised in this period, though the earliest survivals are from the medieval period. Mughal painting represented a fusion of the Persian miniature with older Indian traditions, and from the 17th century its style was diffused across Indian princely courts of all religions, each developing a local style. Company paintings were made for British clients under the British raj, which from the 19th century also introduced art schools along Western lines, leading to modern Indian painting, which is increasingly returning to its Indian roots. KEYWORDS : Indian painting , rock paintings , Indian traditions. INTRODUCTION : Indian paintings provide an aesthetic continuum that extends from the early civilization to the present day. From being essentially religious in purpose in the beginning, Indian painting has evolved over the years to become a fusion of various cultures and traditions. -

Folklore and the Need for Intellectual Property Status: a Study of Phad Painting in Bhilwara District of Rajasthan

International Academic Journal of Law ISSN Print: 2709-9482 | ISSN Online: 2709-9490 Frequency: Bi-Monthly Language: English Origin: Kenya Website: https://www.iarconsortium.org/journal-info/iajl Review Article Folklore and the need for Intellectual Property Status: A Study of Phad Painting in Bhilwara District of Rajasthan Article History Abstract: Humans have a propensity to generate, refine and pass on the knowledge from one generation to another, so that their tradition is conserved Received: 20.04.2021 through several generations. One of the most important aspects of traditional Revision: 30.04.2021 knowledge is “folklore”, which like other forms of traditional knowledge is under Accepted: 10.05.2021 threat of exploitation as a result of too much of technological advancement and Published: 20.05.2021 industrialization. The whole scheme of research is based on the hypothesis that Folklore is required to be protected as an Intellectual property but doesn‟t qualifies Author Details to be an Intellectual Property(IP) under the existing regime and altogether a sui- generis approach by way of legislation or amendment in the existing legislation is Divya Singh Rathor the need of the hour. The existing Intellectual Property(IP) regime is an ineffective Authors Affiliations tool to protect the diverse folklore. Through research, an argument can be primed that whether Rajasthan‟s Phad Painting, a folk art can be socially and legally Assistant Professor, Law (Research Scholar- protected in the form of folklore through a sui-generis protection -

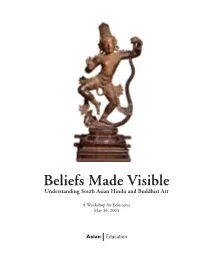

Beliefs Made Visible: Understanding

Beliefs Made Visible Understanding South Asian Hindu and Buddhist Art A Workshop for Educators May 16, 2004 Acknowledgments WORKSHOP MATERIALS PREPARED BY: Brian Hogarth, Director of Education, Asian Art Museum Kristina Youso, PhD, Independent Scholar; Former Assistant Curator, Asian Art Museum Stephanie Kao, School Programs Coordinator, Asian Art Museum WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF: Forrest McGill, PhD, Chief Curator and Wattis Curator of South and Southeast Asian Art, Asian Art Museum Thais da Rosa, PhD, Lowell High School Robin Jacobson, Editorial Associate, Asian Art Museum Jason Jose, Graphics Specialist, Asian Art Museum Kaz Tsuruta, Museum Photographer, Asian Art Museum PHOTOGRAPHY BY: Kalpana Desai Stephen P. Huyler Brian Hogarth Olivier Laude ILLUSTRATIONS BY: Brian Hogarth Stephanie Kao Cover: Krishna overcoming the serpent Kaliya, approx. 1400–1500 India; reportedly from Sundaraperumakoil, Tanjavur district, Tamil Nadu state, former kingdom of Vijayanagara Bronze The Avery Brundage Collection, B65B72 1 Table of Contents 3 Understanding Hinduism 10 Understanding Buddhism 16 Slide Descriptions 58 Lesson Plans, Activities, and Student Worksheets • A Labyrinth for Lakshmi: The Ritual Tradition of Threshold Art 72 Buddhism Student Hand-outs and Worksheets • Eight Scenes of the Buddha’s Life • The Buddha Image • The Visual Language of Buddhist Art 84 Temple Illustrations 87 Buddhist and Hindu Terms 92 References and Further Reading 95 Map of India 2 Understanding Hinduism Understanding Hinduism By Brian Hogarth with contributions by Kristina Youso Hinduism is one of the world’s oldest religions. It has complex roots, and involves a vast array of practices and a host of deities. Its plethora of forms and beliefs reflects the tremendous diversity of India, where most of its one billion followers reside. -

Ghumar: Historical Narratives and Gendered Practices of Dholis in Modern Rajasthan

GHUMAR: HISTORICAL NARRATIVES AND GENDERED PRACTICES OF DHOLIS IN MODERN RAJASTHAN By YASMINE SINGH A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Religion May 2010 Winston-Salem, North Carolina Approved By: Jarrod L. Whitaker, Ph.D., Advisor ____________________________________ Examining Committee: Kenneth G. Hoglund, Ph.D. ____________________________________ Steven J. Folmar, Ph.D. ____________________________________ ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A heartfelt thank you to the all the many individuals in America, India and Nepal, without whose support, guidance and love, this thesis would not have been possible. First, I would like to take this opportunity to thank my committee members; Dr. Jarrod Whitaker, my mentor and advisor, for believing in me and my abilities even when I questioned them; Dr. Steven Folmar, my American bua, for his friendship and for the important instructions in conducting ethnographic fieldwork in Nepal and India; Dr. Kenneth Hoglund for chairing my defense and his comments on this thesis. I was fortunate to work with Dr. Tanisha Ramachandran, who helped me become a stronger writer. I would also like to thank Dr. Marlin Adrian, my Salem College advisor, who introduced me to the fascinating study of Religion. Graduate school would not have been as fun and engaging without Christy Cobb. I thank her for her indispensable friendship, steadfast encouragement and stimulating discussions. I can not forget to mention Sheila Lockhart, who opened the doors to her house when I needed a place to stay; she is truly my home away from home. -

Indian Archaeology 1971-72 a Review

INDIAN ARCHAEOLOGY 1971-72 —A REVIEW EDITED BY M. N. DESHPANDE Director General Archaeological Survey of India ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA GOVERNMENT OF INDIA NEW DELHI 1975 Cover Excavated remains at Surkotada: a Harappan settlement in District Kutch, Gujarat 1975 ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA GOVERNMENT OF INDIA Price : Rs. 24-50 PRINTED AT NABAMUDRAN PRIVATE LTD., CALCUTTA, 700004 PREFACE The publication of the 1971-72 issue of the Review further reduces the number of those issues which had fallen into arrears; the issue for the year 1966-67 is in a press-ready condition and will be sent to the press shortly; the issues for the years 1972-73 and 1973-74 are in various stages of editing. It is hoped that we shall soon be up to date in the publication of the Review. Deeply conscious of the value of the cooperative effort which lies behind such a publication, I take this opportunity of expressing my indebtedness to all the contributors from (i) the universities and other research institutions including the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, (ii) the State Departments of Archaeology, and (iii) my colleagues in the Archaeological Survey of India, for sending their reports and illustrative material for inclusion in the issue. As usual, however, I do not hold myself responsible for the views expressed in the respective reports. Lastly, I would like to thank my own colleagues in the Survey who helped me in the various stages of the publication of this issue, including that of editing and printing. 31 March 1975 M. N. DESHPANDE CONTENTS PAGE I. -

Painting (049) History of India Art

PAINTING (049) HISTORY OF INDIA ART FOR CLASS –XII MANOJ KUMAR PGT FINE ART’S JP ACADEMY MEERUT MOB. : UNIT -1 (The Rajasthani andPahari School of Miniature Paintings) (A) The Rajasthani School ➢ Origin and Development ➢ Characterstics ➢ Paintings Title Artist School 1. Maru ragini Sahibdin Mwar 2. Radha (Bani Thani) Nihal chand Kishangarh 3. Chaugan Players Dana Jodhpur 4. Raja Anirudh Singh Hara Utkal Ram Bundi 5. Bharat meets Ram at Chitrakut Guman Jaipur 6. Krishna on Swing Nurudin Bikaner (B) The Pahari School ➢ Origin and Development ➢ Characterstics ➢ Paintings Title Artist School 7. Krishna with Gopies Manku Basohli 8. Raga Megha Madhodas Kangra Unit -1 Rajput or rajasthani School of painting (16th -19th Century) What is a Miniature Painting? Any Painting done in small size in any medium and on any surface miniature painting. It was generally executed on palm leaves, cloth leather or ivory. Miniature represents its minute details. It may be a portrait, illustration any story or a scene from daily life. Pal School of Painting. Based on incidents of lord Buddha’s life, a lot of short stories had been painted between 8th and 11th centuries in Bengal and its surrounding area. Because these paintings were made in patronage of the kings of the pal dynasty, therefore, these are called the Paintings of Pal Style. Jain School of Painting. In painted pages of “Kalpasutra” there are pictures of preceptors (Tirthankars) as Mahavira, Parshvanath and Neminath. These pictures also are narrative, which have been painted on both-palm leaves as well as cloth. This school use of gold, dark colours, biting bend of limes, rhythmicity and splendour confer liveliness to jain paintings. -

Miniature Painting: a Royal Art of Rajasthan Received: 04-03-2018 Accepted: 06-04-2018 Simran Kaur and Dr

International Journal of Home Science 2018; 4(2): 260-262 ISSN: 2395-7476 IJHS 2018; 4(2): 260-262 © 2018 IJHS Miniature painting: A royal art of Rajasthan www.homesciencejournal.com Received: 04-03-2018 Accepted: 06-04-2018 Simran Kaur and Dr. Amita Walia Simran Kaur Assistant Professor, Institute of Abstract Home Economics, Hauz Khas, This study Attems to Under stand and document the techniques and motifs employé in Rajput Miniature New Delhi, India Painting in contexte of their ritualiste and socio-cultural signifiance. The study documents traditional and present techniques of Miniature Painting and the traditionnel designs in relation to their religious and Dr. Amita Walia philosophico signifiance. It was found that Miniature Painting, which essentially derive its theme from Assistant Professor, Institute of rich heritage of the Mughal and Rajput Royal lives, were previously done on leafs, metal sheets, stones Home Economics, Hauz Khas, and are now practiced on other mediums such as paper and fabric such as silk and cotton. The raw New Delhi, India materials, techniques and motifs used for creating these beautifully detailed paintings are recorded. The paper concludes with the new range of Product being made as per the market demande. Keywords: Paintings, miniature, Rajput painting, silk fabric, shell, Gond, hakik-ka-pathar, kadiya, varakh 1. Introduction Paintings are basically an art form that has flourished in India from early times as is evident from the remains that have been discovered in the caves, and the literary sources. Rajput painting, also known as Rajasthani Painting, is a style of Indian paintings developed and flourished during the 18th century in the royal courts of Rajasthan (3). -

Mehandi in the Marketplace: Tradition, Training, and Innovation in the Henna Artistry of Contemporary Jaipur, India

Museum Anthropology Review Mehandi in the Marketplace: Tradition, Training, and Innovation in the Henna Artistry of Contemporary Jaipur, India Jessica Evans Jain1 State of Tennessee 1c/o Museum Anthropology Review Department of Folklore and Ethnomusicology Indiana University Classroom Office Building Bloomington, IN 47405 United States [email protected] This manuscript was accepted for publication on April 6, 2014. Abstract Henna has been an essential part of women’s traditional body art in many North Indian communi- ties. In recent decades, professional henna artists have expanded their businesses to offer “walk- in” service along the sidewalks of urban market areas in addition to private at-home bookings. This study examines the skills acquisition and execution of Jaipur market henna artists in order to understand how they satisfy a large customer base that demands convenience, application speed, motif variety, and overall design excellence. In addition to conducting interviews with artists and customers, the author received training from and worked alongside a closed sample of artists. Collected market designs were compared to surveyed design booklets and magazines in order to identify elements of continuity and change in designs since 1948. The data revealed that customer demands require artist training that promotes constant innovation that in turn increases popular appeal and vitalizes the tradition of henna application. Keywords artistry; body art; commercial artists; design elements; festivals; henna; markets; mehndi; motifs; occupational training; wedding costumes; wedding parties; India. Topical keywords are drawn from the American Folklore Society Ethnographic Thesaurus, a standard nomenclature for the ethno- graphic disciplines. Competing Interests The author declares no competing interests. -

13-99Z Article Text-35-1-4-20161227

International Journal of Humanities & Social Science: Insights & Transformations Vol. 2, Issue 1 - 2017 RAJASTHAN’S RICH CULTURAL TRADITIONS OF FOLK PAINTINGS AVINASH PAREEK * INTRODUCTION Rajasthan has the rich traditions of practicing folk and the elements related to nature. Some of the paintings since time immemorial. These paintings folk paintings of Rajasthan such as Sanjhya, Phad are as diverse as its culture. The folk paintings in painting, and miniature painting are popular all Rajasthan are purely handmade. They bring to over the world. Folk arts were once the integral the forefront the talent of the Rajasthani part of the common folk’s life and they expressed painters. The folk paintings of Rajasthan deal with the aesthetic and entertainment aspect of the pictorial depictions of popular gods, goddesses, rural folk. human portraits, common customs and rituals, ART: ITS ORIGIN folk art of Rajasthan is capable of giving a lead to the whole Indian folk art.’ 3 The folk paintings of Art is the manifestation of creativity. This is quite Rajasthan have a wide range of variety to offer. clear from the words of Umrao Singh ‘The art has ‘The range of topics in Rajasthan available in the originated from the sense of aesthetics that has form of paintings is so vast that these paintings led man towards the creativity. Consequently the present a whole world covering city, forest, 1 culture was nurtured.’ Thus folk paintings can creature, huts, palaces, forts, wars, vegetation, enable a person to be familiar with the cultural festival, women, sex, meeting, parting, separation 2 aspect. ‘Art is the soul of any culture.’ Besides, etc.