Top of Page Interview Information--Different Title

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Football Coaching Records

FOOTBALL COACHING RECORDS Overall Coaching Records 2 Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) Coaching Records 5 Football Championship Subdivision (FCS) Coaching Records 15 Division II Coaching Records 26 Division III Coaching Records 37 Coaching Honors 50 OVERALL COACHING RECORDS *Active coach. ^Records adjusted by NCAA Committee on Coach (Alma Mater) Infractions. (Colleges Coached, Tenure) Yrs. W L T Pct. Note: Ties computed as half won and half lost. Includes bowl 25. Henry A. Kean (Fisk 1920) 23 165 33 9 .819 (Kentucky St. 1931-42, Tennessee St. and playoff games. 44-54) 26. *Joe Fincham (Ohio 1988) 21 191 43 0 .816 - (Wittenberg 1996-2016) WINNINGEST COACHES ALL TIME 27. Jock Sutherland (Pittsburgh 1918) 20 144 28 14 .812 (Lafayette 1919-23, Pittsburgh 24-38) By Percentage 28. *Mike Sirianni (Mount Union 1994) 14 128 30 0 .810 This list includes all coaches with at least 10 seasons at four- (Wash. & Jeff. 2003-16) year NCAA colleges regardless of division. 29. Ron Schipper (Hope 1952) 36 287 67 3 .808 (Central [IA] 1961-96) Coach (Alma Mater) 30. Bob Devaney (Alma 1939) 16 136 30 7 .806 (Colleges Coached, Tenure) Yrs. W L T Pct. (Wyoming 1957-61, Nebraska 62-72) 1. Larry Kehres (Mount Union 1971) 27 332 24 3 .929 31. Chuck Broyles (Pittsburg St. 1970) 20 198 47 2 .806 (Mount Union 1986-2012) (Pittsburg St. 1990-2009) 2. Knute Rockne (Notre Dame 1914) 13 105 12 5 .881 32. Biggie Munn (Minnesota 1932) 10 71 16 3 .806 (Notre Dame 1918-30) (Albright 1935-36, Syracuse 46, Michigan 3. -

Football Bowl Subdivision Records

FOOTBALL BOWL SUBDIVISION RECORDS Individual Records 2 Team Records 24 All-Time Individual Leaders on Offense 35 All-Time Individual Leaders on Defense 63 All-Time Individual Leaders on Special Teams 75 All-Time Team Season Leaders 86 Annual Team Champions 91 Toughest-Schedule Annual Leaders 98 Annual Most-Improved Teams 100 All-Time Won-Loss Records 103 Winningest Teams by Decade 106 National Poll Rankings 111 College Football Playoff 164 Bowl Coalition, Alliance and Bowl Championship Series History 166 Streaks and Rivalries 182 Major-College Statistics Trends 186 FBS Membership Since 1978 195 College Football Rules Changes 196 INDIVIDUAL RECORDS Under a three-division reorganization plan adopted by the special NCAA NCAA DEFENSIVE FOOTBALL STATISTICS COMPILATION Convention of August 1973, teams classified major-college in football on August 1, 1973, were placed in Division I. College-division teams were divided POLICIES into Division II and Division III. At the NCAA Convention of January 1978, All individual defensive statistics reported to the NCAA must be compiled by Division I was divided into Division I-A and Division I-AA for football only (In the press box statistics crew during the game. Defensive numbers compiled 2006, I-A was renamed Football Bowl Subdivision, and I-AA was renamed by the coaching staff or other university/college personnel using game film will Football Championship Subdivision.). not be considered “official” NCAA statistics. Before 2002, postseason games were not included in NCAA final football This policy does not preclude a conference or institution from making after- statistics or records. Beginning with the 2002 season, all postseason games the-game changes to press box numbers. -

2018 Cal Football Record Book.Pdf

CALIFORNIA GOLDEN BEARS FOOTBALL TABLE OF CONTENTS Media Info .................................................................1 2018 Year In Review ..............................................12 Records ..................................................................42 History .....................................................................70 This Is Cal ............................................................ 120 2018 PRESEASON CALIFORNIA FOOTBALL NOTES WILCOX BEGINS SECOND SEASON IN 2018 CAL IN SEASON OPENERS • Justin Wilcox is in his second season as the head football coach at • Cal opens the 2018 season in Berkeley when the Bears host North Cal in 2018. After leading some of the top defenses in the nation as Carolina in the second-ever meeting ever between the teams. Cal won an FBS defensive coordinator for 11 seasons prior to his arrival at the first meeting, 35-30, in the 2017 season-opener in Chapel Hill, Cal in January of 2017, Wilcox posted a 5-7 overall mark in his first N.C. The Bears have won their last season openers. campaign at the helm of the Golden Bears. • The highlights of his first season as the head coach in Berkeley in NATIONAL HONORS CANDIDATE PATRICK LAIRD 2017 included a 3-0 start that featured wins over North Carolina and • Running back Patrick Laird is a national honors candidate and on Ole Miss, as well as a 37-3 victory over then No. 8/9 Washington State the preseason watch list for the Maxwell Award given annually to in an ESPN nationally-televised Friday night home game. The victory America's College Football Player of the Year in 2018 after a breakout against the Cougars snapped Cal's 17-game losing streak to top-10 2017 junior season when he earned honorable mention All-Pac-12 teams, was the Bears' first victory against a top-10 team since 2003 honors and was one of 10 national semifinalists for the Burlsworth and only its second top-10 win since 1977. -

Citadel Vs Clemson (9/12/1970)

Clemson University TigerPrints Football Programs Programs 1970 Citadel vs Clemson (9/12/1970) Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/fball_prgms Materials in this collection may be protected by copyright law (Title 17, U.S. code). Use of these materials beyond the exceptions provided for in the Fair Use and Educational Use clauses of the U.S. Copyright Law may violate federal law. For additional rights information, please contact Kirstin O'Keefe (kokeefe [at] clemson [dot] edu) For additional information about the collections, please contact the Special Collections and Archives by phone at 864.656.3031 or via email at cuscl [at] clemson [dot] edu Recommended Citation University, Clemson, "Citadel vs Clemson (9/12/1970)" (1970). Football Programs. 87. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/fball_prgms/87 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Programs at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Football Programs by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Official Program Published By ATHLETIC DEPARTMENT CLEMSON UNIVERSITY Edited By BOB BRADLEY Director of Sports Information Assisted By JERRY ARP Ass't. Sports Information Director Represented for National Advertising By SPENCER MARKETING SERVICES 370 Lexington Avenue New York, New York 10017 Photography by Jim Burns, Charles Haralson, Tom Shockley, Hal Smith, and Bill Osteen of Clemson; Jim Laughead and Jim Bradley of Dallas, Texas IMPORTANT EMERGENCIES: A first aid station is located LOST & FOUND: If any article is lost or found, under Section A on South side of Stadium. please report same to Gate 1 Information Booth. -

NCAA Division I Football Records (Coaching Records)

Coaching Records All-Divisions Coaching Records ............. 2 Football Bowl Subdivision Coaching Records .................................... 5 Football Championship Subdivision Coaching Records .......... 15 Coaching Honors ......................................... 21 2 ALL-DIVISIONS COachING RECOrds All-Divisions Coaching Records Coach (Alma Mater) Winningest Coaches All-Time (Colleges Coached, Tenure) Yrs. W L T Pct.† 35. Pete Schmidt (Alma 1970) ......................................... 14 104 27 4 .785 (Albion 1983-96) BY PERCENTAGE 36. Jim Sochor (San Fran. St. 1960)................................ 19 156 41 5 .785 This list includes all coaches with at least 10 seasons at four-year colleges (regardless (UC Davis 1970-88) of division or association). Bowl and playoff games included. 37. *Chris Creighton (Kenyon 1991) ............................. 13 109 30 0 .784 Coach (Alma Mater) (Ottawa 1997-00, Wabash 2001-07, Drake 08-09) (Colleges Coached, Tenure) Yrs. W L T Pct.† 38. *John Gagliardi (Colorado Col. 1949).................... 61 471 126 11 .784 1. *Larry Kehres (Mount Union 1971) ........................ 24 289 22 3 .925 (Carroll [MT] 1949-52, (Mount Union 1986-09) St. John’s [MN] 1953-09) 2. Knute Rockne (Notre Dame 1914) ......................... 13 105 12 5 .881 39. Bill Edwards (Wittenberg 1931) ............................... 25 176 46 8 .783 (Notre Dame 1918-30) (Case Tech 1934-40, Vanderbilt 1949-52, 3. Frank Leahy (Notre Dame 1931) ............................. 13 107 13 9 .864 Wittenberg 1955-68) (Boston College 1939-40, 40. Gil Dobie (Minnesota 1902) ...................................... 33 180 45 15 .781 Notre Dame 41-43, 46-53) (North Dakota St. 1906-07, Washington 4. Bob Reade (Cornell College 1954) ......................... 16 146 23 1 .862 1908-16, Navy 1917-19, Cornell 1920-35, (Augustana [IL] 1979-94) Boston College 1936-38) 5. -

Utah Vs. "Arizona State MECOMING

OFFICIAL PROGRAM 50 * Utah vs. "Arizona State MECOMING IN THIS ISSUE: Who That Horse Is" Tomorrow, Sunday, Nov. 5 Chicago vs. Detroit 11:00 a. m. New York vs. Minnesota 1:30 p. m. • • ' MOUNTAIN AMERICA'S NUMBER ONE SPORTS STATION the big f>Jay : The big play these days is to Hotel Utah. And little wonder! It's all new, from the ground up. New chandeliers, new furniture, new carpets, new draperies, new lighting and fresh new colors everywhere. Food? The best! Dancing? You bet! Ted Johnson and his orchestra are back for the Fall and Winter season. Sunday Brunch, too — and the musical fashion show luncheon each Monday. Make the big play. Live it up! Why not start tonight? Hotel Utah New again... and fresh as a flower! H. N. (Hank) Aloia, Managing Director OFFICIAL PROGRAM OFFICIAL WATCH TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THIS GAME Today's Game __ 2 "Welcome Alumni" President James C. Fletcher 3 •**••** Dr. G. Homer Durham, President, Arizona State University 4 Clyde B. Smith, Athletic Director, Arizona State University 4 LONGINES The Arizona State Campus 7 THE WORLD'S Utah Alumni Association, (Utah Man) 8 MOST HONORED Utah Marching Band 9 WATCH® Head Coach Frank Kush, Arizona State 10 10 world's fair grand prizes Meet the Sun Devils ...11, 13, 15, 17 28 gold medals w Arizona State Assistants 12 Arizona State Alphabetical Roster 21 Longines watches are recognized as OFFICIAL for timing world "Who That Horse Is" Roy McHugh 22 championships and Olympic sports Arizona State Seven Game Statistics 23 in all fields throughout the world. -

Washington Evergreen STATE COLLEGE of WASHINGTON, PULLMAN, WASH

All-ALI-All Coast Coaches came through with choices for Another all-team is selected by all-coast teams, from which Columnist Bob Miller on page Sports Editor Salt compiled Evergreen all-coast elevens. four of today's Evergreen. Washington Evergreen STATE COLLEGE OF WASHINGTON, PULLMAN, WASH.. MONDAY, NOVEMBER 29,1937 NO. 31 VOL. XLIV Z799 Ticket I-Iolders May Obtain e17 See That I:vergreen Sports I:ditor MaryDUTga~I Compiles Two All-Coast Tearns Varsity Ball Programs Wednesday eoes on rla I i s-------------------------------------------------------- Conference Coaches Chairman Fa usti This Is No Joke, Aid Scribe in Names Patrons For DZ's Want Flivver Accidents Prod:cti:n ;taff EVERGREEN ALL-COAST I Choosing Elevens Dance, December 4 Lost, Strayed or Stolen: One Del- Selected for Play COACI-I~S' S~L~CTIONS ta Zeta flivver, prohably 1926 mod- Invalve Five By Prof. Daggy Results of an All-Coast conference Varsity Ball programs will be on el, Friday night. "We want our FIRST TEAM coacl;es poll, conducted by Lloyd distribution to all ticket-holders at f liv vcr," Delta Zetas said today. Seventeen persons were appointed Salt. Evergrec n sports editor, were the Bookstore \N edne sday, Remo "This is no time to joke." JVIotorists Escape today to see that Mary Dugan, petite Position Player College Votes aunounrc d today. First and second Fausti, chairman, said Saturday. "We parked it in a safe place he- I Serious Injury in star of the New York "Follies." goes L.E. GRANT STONE, Stanford (6) ,E,Trgreen All-Coast teams appear In keeping with the general theme side the house and when we wanted on trial for her life January 7 and 8 L.T. -

2003 Husky Football

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON 2003 HUSKY FOOTBALL www.gohuskies.com Contacts: Jim Daves, Jeff Bechthold & Brian Beaky • (206) 543-2230 • Fax (206) 543-5000 2003 HUSKY SCHEDULE / RESULTS #17/19 WASHINGTON at #2/2 OHIO STATE Aug. 30 at Ohio State (ABC-TV) 5:00 p.m. Gilbertson Era Kicks Off at Horseshoe vs. Defending Champs Sept. 6 INDIANA (Fox Sports Net) 1:00 p.m. Sept. 20 IDAHO 12:30 p.m. THE GAME: The Washington football team, ranked No. 17 in the Associated Press preseason poll and No. Sept. 27 STANFORD 12:30 p.m. 19 in this week’s ESPN coaches’ poll, opens its 2003 season vs. second-ranked Ohio State, the team that beat Oct. 4 at UCLA 12:30 p.m. Miami (Fla.) in last year’s BCS Championship game at the Fiesta Bowl. The game, which kicks off at 5:00 p.m. Oct. 11 NEVADA 12:30 p.m. (PDT) Saturday at Ohio Stadium, marks the UW’s first game under new head coach Keith Gilbertson, a Se- Oct. 18 at Oregon State 1:00 p.m. attle-area native who had previously served as a grad assistant, assistant coach and offensive coordinator at Washington. This season is the beginning of Gilbertson’s third stint as a head coach as he previously oversaw Oct. 25 USC (ABC-TV) 12:30 p.m. the programs at Idaho (1986-88) and California (1992-95). Nov. 1 OREGON (TBS) 7:00 p.m. Nov. 8 at Arizona 3:00 p.m. HUSKIES vs. BUCKEYES HISTORY: Ohio State boasts a 6-3 record in its nine all-time meetings with Nov. -

Gen. Robert R. Neyland 06.Qxd

2006 GUIDE GEN. ROBERT R. NEYLAND Gen. Robert R. Neyland General Robert Reese Neyland Trophy Honorees Feb. 17, 1892 - March 28, 1962 The history and tradition of Tennessee football began under the In 1967, the Knoxville Quarterback Club, tutelage of Gen. Robert Reese Neyland, a member of the College seeking a way to honor Gen. Neyland’s memo- Football Hall of Fame. Neyland came to Tennessee as an ROTC ry, established the Robert R. Neyland Memorial instructor and backfield coach in 1925 and was named head foot- Trophy. This award is given annually by the ball coach in 1926. From that date, Tennessee was in the college Club to an outstanding man who has con- football business to stay. tributed greatly to intercollegiate athletics. The Neyland’s 1939 Vol team was the last to shut out each of its reg- first presentation in 1967 included the man ular season opponents. Over the course of his career, 112 of his 216 opponents failed to score against his Tennessee teams. Tennessee who hired Gen. Neyland in 1926 and his first still holds an NCAA record for holding opponents scoreless 71 con- All-America lineman, who later became head secutive quarters. coach at Yale. The permanent trophy is dis- Neyland’s teams won Southern Conference Championships in played in the Tennessee Hall of Fame Exhibit in 1927 and 1932, piling up undefeated streaks of 33 and 28 games the Neyland-Thompson Sports Center. along the way, and SEC Championships in 1938, 1939, 1940, 1946 and 1951. In addition Neyland-coached teams won four national 1967 - Nathan W. -

09FB Guide P163-202 Color.Indd

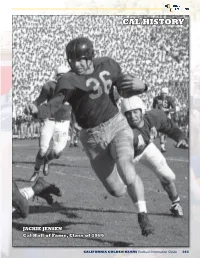

CCALAL HHISTORYISTORY JJACKIEACKIE JJENSENENSEN CCalal HHallall ooff FFame,ame, CClasslass ooff 11986986 CALIFORNIA GOLDEN BEARS FootballFtbllIf Information tiGid Guide 163163 HISTORY OF CAL FOOTBALL, YEAR-BY-YEAR YEAR –––––OVERALL––––– W L T PF PA COACH COACHING SUMMARY 1886 6 2 1 88 35 O.S. Howard COACH (YEARS) W L T PCT 1887 4 0 0 66 12 None O.S. Howard (1886) 6 2 1 .722 1888 6 1 0 104 10 Thomas McClung (1892) 2 1 1 .625 1890 4 0 0 45 4 W.W. Heffelfi nger (1893) 5 1 1 .786 1891 0 1 0 0 36 Charles Gill (1894) 0 1 2 .333 1892 Sp 4 2 0 82 24 Frank Butterworth (1895-96) 9 3 3 .700 1892 Fa 2 1 1 44 34 Thomas McClung Charles Nott (1897) 0 3 2 .200 1893 5 1 1 110 60 W.W. Heffelfi nger Garrett Cochran (1898-99) 15 1 3 .868 1894 0 1 2 12 18 Charles Gill Addison Kelly (1900) 4 2 1 .643 Nibs Price 1895 3 1 1 46 10 Frank Butterworth Frank Simpson (1901) 9 0 1 .950 1896 6 2 2 150 56 James Whipple (1902-03) 14 1 2 .882 1897 0 3 2 8 58 Charles P. Nott James Hooper (1904) 6 1 1 .813 1898 8 0 2 221 5 Garrett Cochran J.W. Knibbs (1905) 4 1 2 .714 1899 7 1 1 142 2 Oscar Taylor (1906-08) 13 10 1 .563 1900 4 2 1 53 7 Addison Kelly James Schaeffer (1909-15) 73 16 8 .794 1901 9 0 1 106 15 Frank Simpson Andy Smith (1916-25) 74 16 7 .799 1902 8 0 0 168 12 James Whipple Nibs Price (1926-30) 27 17 3 .606 1903 6 1 2 128 12 Bill Ingram (1931-34) 27 14 4 .644 1904 6 1 1 75 24 James Hopper Stub Allison (1935-44) 58 42 2 .578 1905 4 1 2 75 12 J.W. -

Ernie Davis Legends Field and Syracuse’S Nationally-Recognized Football, Basketball and Lacrosse Programs

Success on the Field Success in • The ACC is the second conference to win both the national championship and another BCS game in the Classroom the same year (fi fth time overall). The league is Of the ACC’s 14 football teams, 12 schools rank 3-0 in BCS games over the last two years. among the top 70 institutions in the most recent • The ACC is the fi rst conference in history to U.S. News & World Report survey of “America’s sweep the Heisman, Doak Walker, Davey O’Brien, Best Colleges,” more than any other FBS Outland, Lombardi, Bednarik and Nagurski conference. awards in the same year. • Four of ABC’s nine highest-rated and most- ACC 12 viewed national college football telecasts this season featured ACC teams, including three conference matchups. Big Ten 8 American 6 Tradition of Success Pac-12 6 ACC teams have a national title since 136 the league’s inception in 1953 SEC 4 women’s national titles 71 Big 12 1 65 men’s national titles Syracuse defeated Minnesota in the 2013 Texas Bowl for its third bowl victory in the last four years. Overall, the Orange has earned invitations to every bowl game that is part of the playoff system and played in 25 post-season games. The victory against the Golden Gophers was the program’s 15th bowl triumph. Orange Bowl (Jan. 1, 1953) Alabama 61, Syracuse 6 Cotton Bowl (Jan. 1, 1957) TCU 28, Syracuse 27 Orange Bowl (Jan. 1, 1959) Oklahoma 21, Syracuse 6 Cotton Bowl (Jan. 1, 1960) Syracuse 23, Texas 14 Liberty Bowl (Dec. -

82Nd Annual Convention of the AFCA

82nd annual convention of the AFCA. JANUARY 9-12, 2005 * LOUISVILLE, KENTUCKY President's Message It was an ordinary Friday night high school football game in Helena, Arkansas, in 1959. After eating our pre-game staples of roast beef, green beans and dry toast, we journeyed to the stadium for pre- game. As rain began to fall, a coach instructed us to get in a ditch to get wet so we would forget about the elements. By kickoff, the wind had increased to 20 miles per hour while the temperature dropped over 30 degrees. Sheets of ice were forming on our faces. Our head coach took the team to the locker room and gave us instructions for the game as we stood in the hot showers until it was time to go on the field. Trailing 6-0 at halftime, the officials tried to get both teams to cancel the game. Our coach said, "Men, they want us to cancel. If we do, the score will stand 6-0 in favor of Jonesboro." There was a silence broken by his words, "I know you don't want to get beat 6-0." Well, we finished the game and the final score was 13-0 in favor of Jonesboro. Forty-five years later, it is still the coldest game I have ever been in. [ILLUSTRATION OMITTED] No one likes to lose, but for every victory, there is a loss. As coaches, we must use every situation to teach about life and how champions handle both the good and the bad. I am blessed to work with coaches who care about each and every player.