Touching Base: Race, Sport, and Community in Newport

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

White, George "Tubber"

1 George “Tubber” White Collection Cambridge Historical Commission 831 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139 Dates 1912-1920s Extent 1 half record box Access Collection is available for research; CHC rules of use apply. Processing and finding aid completed by Megan Schwenke, September 2012 Provenance and Collection Description The George “Tubber” White collection was donated to the Commission in October of 2007 by David Grant of Cambridge, Massachusetts. Mr. Grant found the materials on Summer Street in Somerville a year prior to donation. This collection includes hockey, football, and baseball team photographs featuring George “Tubber” White during his time at Rindge Technical School and Exeter Academy. White's athletic exploits at Rindge are also captured in 20 scrapbook pages of newspaper clippings, where he is referred to as George White and “Tubber” White interchangeably. The collection also includes eleven photo postcard featuring members of the North Cambridge semi- professional baseball team, of which White was a member in the 1920s. Biographical Note George “Tubber” White (1895-1977) was one of eight children born to William A. White and Mrs. White of Cambridge. He was raised in Cambridge, and was a celebrated local sports star. He attended Rindge Technical School from 1911 until 1915, where he acted as captain for the baseball, football, and hockey teams, and in 1913 was a 1st team Boston American All-Scholastic Football Selection. White entered Exeter Academy in the fall of 1915, and was the captain of the hockey team there as well, while also playing on the football and baseball teams. He served in the Navy from 1916 to 1918, and enrolled in Boston College after his discharge in 1918, where 2 he played on the varsity football team. -

Landscapes Summer 2021

Allow me to introduce myself My name is Jeff Norte and I was recently selected as the new president and chief executive officer of Capital Farm Credit. Although I’m new to the role, I’m not new to Capital Farm Credit. I’ve been fortunate to be part of the leadership team here for more than 10 years as chief credit officer. I’ve had the great benefit of working with, and learning from, one of the best in Ben Novosad, who served as CEO for 35 years. It is an incredible honor for me to follow in Ben’s footsteps to lead and serve such a great company. It is through his long-tenured leadership that our association was able to grow into what it is today. We are a strong and stable organization with a depth of knowledge and experience keenly positioned to help you achieve your dreams. As a cooperative, Capital Farm Credit is owned by you — the ranchers, farmers, landowners and rural homeowners we serve. We have a long tradition of sup- porting agriculture and rural communities with reliable, consistent credit and financial services. We’ve faithfully served our customers for more than a century. As we begin this journey together, I assure you Capital Farm Credit will con- tinue our absolute commitment to providing service and value to our members. And we will remain focused on our core values of commitment, trust, value and family. These values are the daily reminders of why we do what we do. I look forward to getting to know you better. -

Numbered Panel 1

PRIDE 1A 1B 1C 1D 1E The African-American Baseball Experience Cuban Giants season ticket, 1887 A f r i c a n -American History Baseball History Courtesy of Larry Hogan Collection National Baseball Hall of Fame Library 1 8 4 5 KNICKERBOCKER RULES The Knickerbocker Base Ball Club establishes modern baseball’s rules. Black Teams Become Professional & 1 8 5 0 s PLANTATION BASEBALL The first African-American professional teams formed in As revealed by former slaves in testimony given to the Works Progress FINDING A WAY IN HARD TIMES 1860 – 1887 the 1880s. Among the earliest was the Cuban Giants, who Administration 80 years later, many slaves play baseball on plantations in the pre-Civil War South. played baseball by day for the wealthy white patrons of the Argyle Hotel on Long Island, New York. By night, they 1 8 5 7 1 8 5 7 Following the Civil War (1861-1865), were waiters in the hotel’s restaurant. Such teams became Integrated Ball in the 1800s DRED SCOTT V. SANDFORD DECISION NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BA S E BA L L PL AY E R S FO U N D E D lmost as soon as the game’s rules were codified, Americans attractions for a number of resort hotels, especially in The Supreme Court allows slave owners to reclaim slaves who An association of amateur clubs, primarily from the New York City area, organizes. R e c o n s t ruction was meant to establish Florida and Arkansas. This team, formed in 1885 by escaped to free states, stating slaves were property and not citizens. -

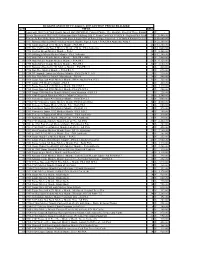

PDF of August 17 Results

HUGGINS AND SCOTT'S August 3, 2017 AUCTION PRICES REALIZED LOT# TITLE BIDS 1 Landmark 1888 New York Giants Joseph Hall IMPERIAL Cabinet Photo - The Absolute Finest of Three Known Examples6 $ [reserve - not met] 2 Newly Discovered 1887 N693 Kalamazoo Bats Pittsburg B.B.C. Team Card PSA VG-EX 4 - Highest PSA Graded &20 One$ 26,400.00of Only Four Known Examples! 3 Extremely Rare Babe Ruth 1939-1943 Signed Sepia Hall of Fame Plaque Postcard - 1 of Only 4 Known! [reserve met]7 $ 60,000.00 4 1951 Bowman Baseball #253 Mickey Mantle Rookie Signed Card – PSA/DNA Authentic Auto 9 57 $ 22,200.00 5 1952 Topps Baseball #311 Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 40 $ 12,300.00 6 1952 Star-Cal Decals Type I Mickey Mantle #70-G - PSA Authentic 33 $ 11,640.00 7 1952 Tip Top Bread Mickey Mantle - PSA 1 28 $ 8,400.00 8 1953-54 Briggs Meats Mickey Mantle - PSA Authentic 24 $ 12,300.00 9 1953 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 (MK) 29 $ 3,480.00 10 1954 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 58 $ 9,120.00 11 1955 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 20 $ 3,600.00 12 1952 Bowman Baseball #101 Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 6 $ 480.00 13 1954 Dan Dee Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 15 $ 690.00 14 1954 NY Journal-American Mickey Mantle - PSA EX-MT+ 6.5 19 $ 930.00 15 1958 Yoo-Hoo Mickey Mantle Matchbook - PSA 4 18 $ 840.00 16 1956 Topps Baseball #135 Mickey Mantle (White Back) PSA VG 3 11 $ 360.00 17 1957 Topps #95 Mickey Mantle - PSA 5 6 $ 420.00 18 1958 Topps Baseball #150 Mickey Mantle PSA NM 7 19 $ 1,140.00 19 1968 Topps Baseball #280 Mickey Mantle PSA EX-MT -

Faded Glory Sandy Springs Reporter Article

April 17, 2009 The team won a couple of local championships but after years on the soap opera “Guiding Light”; Chris character. Cohen said Davidson hadn’t worked on the broke up after its members moved around the Bruno, who also was in California with a successful show for a year before that, and he hasn’t acted Roy Hobbs hits the home run at the end of “The country. acting career that included playing the sheriff on the since. But the juxtaposition between the death of his Natural.” Jimmy Chitwood makes the jump shot at USA TV series “The Dead Zone”; Chad Brown, who acting career in New York and the rebirth of Network the end of “Hoosiers.” Even Willie Mays Hayes scores Encouraged by the crew, Cohen decided adult was traveling the world as a top pro player in poker in Phoenix proved to be a powerful addition to the the winning run on Jake Taylor’s bunt at the end of amateur baseball could make an interesting tournaments; and Terry Gatens, who also had movie, the filmmaker said. “Major League.” documentary, so he raised about $29,000 and took a followed his acting career to California but had been three-man crew to Phoenix for the 2006 NABA World estranged from Cohen since 2000 and was doing a 90- All of the guys also got something more than It’s so common for the good guys to pull off the Series. He said the footage was good, and he put day rehab stint at the Betty Ford Clinic for drug and competition out of the experience, Cohen said. -

All-Star Ballpark Heaven Economic and Fiscal Impact Study

All-Star Ballpark Heaven Economic and Fiscal Impact Study A Two-Phased Development Plan By Mike Lipsman Harvey Siegelman With the assistance of Wendol Jarvis Strategic Economics Group Des Moines, Iowa February 2012 www.economicsgroup.com Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 Introduction 4 Purpose and Scope of the Study 4 Background 5 Description of the Area 5 All-Star Ballpark Heaven Proposal 7 Development Plan 7 Tournament and Training Program 8 Marketing, Operations and Staffing 9 Youth Baseball-Softball Training and Tournament Facility Market Analysis 10 Team Baseball and Softball Markets 10 Cooperstown Dreams Park 12 Ripken Baseball Group 13 Economic Impact 14 Local Area Demographic and Economic Profile 14 Economic Impact Estimates 18 Supply and Demand for Local Lodging 24 Area Lodging Supply 25 Fiscal Impact Estimates 28 Study Area and State Fiscal Trends 28 Individual Income Tax and Surtax 28 State and Local Option Sales Taxes 29 Hotel-Motel Taxes 31 Property Tax 31 Fiscal Impact Estimates 33 Individual Income Tax and Surtax 33 State and Local Option Sales Taxes 34 Hotel-Motel Taxes 36 Property Taxes 36 Fiscal Impact Estimates Summary 38 Appendix A - Input-Output Methodology 39 Appendix B - Statewide Input-Output Tables for All-Star Ballpark Heaven 41 Appendix C - Regional Input-Output Tables for All-Star Ballpark Heaven 45 Appendix D - Input-Output Model Assumptions 49 Appendix E - Visitor Attractions in the Surrounding Area 50 Appendix F - Go the Distance Baseball Projected Income and Expenses 53 Appendix G - Build Out Schedule - Completed Capital Development 54 2 All-Star Ballpark Heaven: Economic and Fiscal Impact Study Executive Summary Youth sports activity is big business and getting bigger. -

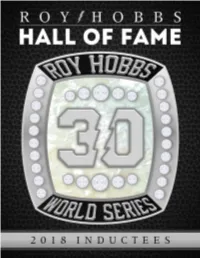

2018 Roy Hobbs Hall of Fame Yearbook

3 4 Roy Hobbs 2018 Hall of Fame Index Memories – Hall of Famers .................... Page 2/27 Welcome to the Hall ............................ Pages 14-15 Hall of Fame Members..................................Page 5 2018 – Steve Eddy .........................................Page 17 Hall of Fame Welcome ..................................Page 6 2018 – Rich Knight ........................................Page 18 Hall of Fame Selection Process ...................Page 7 2018 – Rick Scheetz ......................................Page 19 2018 – Joe Adams ............................................Page 8 2018 – Mike Shevlin .....................................Page 20 2018 – Rob Fester ...........................................Page 9 Revisiting 2017 Celebration .......................Page 22 2018 – Jim Corte ............................................Page 11 Ambassador of Baseball Award ....... Pages 23-24 2018 – Paul Doucette ...................................Page 13 Hall of Fame Collage.............................. Back Cover 2018 Roy Hobbs Hall of Fame Trustees Co-Chairs: Carl Rakich, Florida (2016-2021) & Tom Giffen, Florida (2017-2022); Members: Bill Devine, Pennsylvania (2018-2020), Gary Dover, Tennessee (2017-2019), Tommy Faherty, New Jersey (2016-2018), Rob Giffen, South Carolina (2015-2020), JD Hinson, North Carolina (2017-2019),Ted Lesiak, Ohio (2017-2019), Joe Maiden, California (2016-2018), Bob Misko, Florida (2017-2019), Mike Murphey, Washington (2016-2018), Glenn Miller, Florida (2016-2018), Bill Russo, Ohio (2018-2020), Carroll -

Here Al Lang Stadium Become Lifelong Readers

RWTRCover.indd 1 4/30/12 4:15 PM Newspaper in Education The Tampa Bay Times Newspaper in Education (NIE) program is a With our baseball season in full swing, the Rays have teamed up with cooperative effort between schools the Tampa Bay Times Newspaper in Education program to create a and the Times to promote the lineup of free summer reading fun. Our goals are to encourage you use of newspapers in print and to read more this summer and to visit the library regularly before you electronic form as educational return to school this fall. If we succeed in our efforts, then you, too, resources. will succeed as part of our Read Your Way to the Ballpark program. By reading books this summer, elementary school students in grades Since the mid-1970s, NIE has provided schools with class sets three through five in Citrus, Hernando, Hillsborough, Manatee, Pasco of the Times, plus our award-winning original curriculum, at and Pinellas counties can circle the bases – first, second, third and no cost to teachers or schools. With ever-shrinking school home – and collect prizes as they go. Make it all the way around to budgets, the newspaper has become an invaluable tool to home and the ultimate reward is a ticket to see the red-hot Rays in teachers. In the Tampa Bay area, the Times provides more action at Tropicana Field this season. than 5 million free newspapers and electronic licenses for teachers to use in their classrooms every school year. Check out this insert and you’ll see what our players have to say about reading. -

Cardines Field the GREEN LIGHT

x : : ‘1 7 1 c G R E E K LIGHT Bu l l e t i n oe T h e P o i n t A s s o c i a t i o n OF N e w p o r t, TTh o d e I s l a n d Summer 1997 Cardines Field The GREEN LIGHT XLII No. 2 Summer 1997 Features Green Light President’s Letter 3 A c tin g E d ito ria l B o a r d Beth Cullen (848-2945) Amistad 4 Rowan Howard (847-8428) Kay O’Brien (847-7311) Point Association News 8 Anne Reynolds (847-2009) Dorothy Holt Manuel 9 Advertising and Word P ro c e ssin g Sue Gudikunst (849-4367) Cardines Field 10 B o a r d Liaiso n Star of the Sea Update 12 Beth Cullen (848-2945) 420 World Sailing Championship 14 Circulation Beverly Adler (846-1142) Photo Credits: Kay O’Brien (847-7311) JoyScott Roberto Bessin Tama Sperling (847-4986) Laura Jenifer Mike Cullen Paul Quatracci War College Museum Copies of theGreen Light may be purchased for A rt W ork: $1.00 at Bucci’s Convenience Store; Poplar and Dorothy Sanschagrin Thames; Aidinoff’s Liquor and Gourmet Shop, Eleanor Weaver Warner Street; Clipper W ine & Spirits, Third Street; The Rum Runner, Goat Island; and The Walnut Front Cover: Market, Third & Walnut. Photo of Dorothy Manuel painting The Point Association Board Officers Committees Coles Mallory, President Adventure Club Noise Abatement (849-5659) Beth Lloyd (849-8071) Mike Cullen (848-2945) Donna Segal, P' Vice President Beautification Nominating (848-7088) Deborah Herrington (848-9735) Christine Montanaro (849-4708) Anne Bidstrup, 2"'' Vice President Paul & Nancy Quatrucci (846-2434) Phone (849-1354) Green Lisht Anne Bidstrup (849-1354) Loretta Goldrick, Corresponding Beth Cullen (848-2945) Publicity Secretary (849-9425) History and Archives Dick & Cheryl Poholek (849-3411) Ben Gilson, Recording Secretary Marjorie Magruder (849-3045) Traffic (847-9243) Membershin Mark Williams (849-1319) Philip Mosher, Treasurer Nancy Espersen (846-2907) Waterfront (849-4708) Don Dery (847-8351) Board meetings are scheduled fo r the first Monday o f the Month, 7:00 p.m. -

1953 Topps, a Much Closer Look

In 1984, Lew Lipset reported that Bob Sevchuk reconstructed the first print run Sheets A and B. 1953 Topps, a much closer look By George Vrechek Tom Billing of Springfield, Ohio, is a long-time collector of vintage baseball cards. Billing is among a small group of collectors who continue to stay enthused about old cardboard by discovering and collecting variations, printing differences and other oddities. Often such discoveries are of interest to a fairly limited audience. Occasionally though, such discoveries amount to a loose string that, if pulled, unravel mysteries of interest to many. I pulled on one of Tom’s strings recently. Sid Hudson throws the first curve The “string” that Billing sent me was an image of a miscut 1953 Topps of Sid Hudson. The right edge of the base of the off-centered card had a tiny sliver of black to the right of the otherwise red base nameplate. Was this a variation, a printing difference or none of the above? Would anyone care? As I thought about it, I voted for none of the above since it was really just a miscut card showing some of the adjacent card on the print sheet. But wait a minute! That shouldn’t have happened with the 1953 Topps. Why not? We will see. The loose string was an off-center Lou Hudson showing an adjacent black border. An almost great article Ten years ago I wrote an SCD article about the printing of the 1952 Topps. I received some nice feedback on that effort in which I utilized arithmetic, miscuts and partial sheets to offer an explanation of how the 1952 set was printed and the resulting scarcities. -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

Legal Document

PlainSite® Legal Document New York Southern District Court Case No. 1:13-cv-07097 Rodriguez v. Major League Baseball et al Document 1 View Document View Docket A joint project of Think Computer Corporation and Think Computer Foundation. Cover art © 2015 Think Computer Corporation. All rights reserved. Learn more at http://www.plainsite.org. Case 1:13-cv-07097-LGS Document 1 Filed 10/07/13 Page 1 of 41 LD JUDGE SGr &m I tr UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK x ALEXANDER EMMANUEL RODRIGUEZ, Plaintiff, Civ ICE OI' REMOVAL MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL, OFFICE OF THE COMMISSIONER OF MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL Gild ALLAN HUBER "BUD" SELIG, Dcfcndants. To: TIIF. UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YO PLEASE TAKE NOTICE that Defendants Major League Baseball, The Office of the Commissioner of Baseball (improperly named herein as Office of the Commissioner of Major League Baseball), and Allan Huber "Bud" Selig ("Defendants" ), by and through their undersigned attorneys, Proskauer Rose LLP, hereby file this Notice of Removal of thc above- captioned action to the United States District Court for the Southern District of Ncw York from the Supreme Court of the State of New York, County of New York, where the action is now pending, as provided by Title 28, United States Code, Chapter 89, and now states: 1. The above-captioned action was commenced in the Supreme Court of the State of New York, County of New York (Index No. 653436/2013), and is now pending in that court. No further proceedings have been had therein.