March 15, 2019 the FOUR-RING CIRCUS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North American Company Profiles 8X8

North American Company Profiles 8x8 8X8 8x8, Inc. 2445 Mission College Boulevard Santa Clara, California 95054 Telephone: (408) 727-1885 Fax: (408) 980-0432 Web Site: www.8x8.com Email: [email protected] Fabless IC Supplier Regional Headquarters/Representative Locations Europe: 8x8, Inc. • Bucks, England U.K. Telephone: (44) (1628) 402800 • Fax: (44) (1628) 402829 Financial History ($M), Fiscal Year Ends March 31 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 Sales 36 31 34 20 29 19 50 Net Income 5 (1) (0.3) (6) (3) (14) 4 R&D Expenditures 7 7 7 8 8 11 12 Capital Expenditures — — — — 1 1 1 Employees 114 100 105 110 81 100 100 Ownership: Publicly held. NASDAQ: EGHT. Company Overview and Strategy 8x8, Inc. is a worldwide leader in the development, manufacture and deployment of an advanced Visual Information Architecture (VIA) encompassing A/V compression/decompression silicon, software, subsystems, and consumer appliances for video telephony, videoconferencing, and video multimedia applications. 8x8, Inc. was founded in 1987. The “8x8” refers to the company’s core technology, which is based upon Discrete Cosine Transform (DCT) image compression and decompression. In DCT, 8-pixel by 8-pixel blocks of image data form the fundamental processing unit. 2-1 8x8 North American Company Profiles Management Paul Voois Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Keith Barraclough President and Chief Operating Officer Bryan Martin Vice President, Engineering and Chief Technical Officer Sandra Abbott Vice President, Finance and Chief Financial Officer Chris McNiffe Vice President, Marketing and Sales Chris Peters Vice President, Sales Michael Noonen Vice President, Business Development Samuel Wang Vice President, Process Technology David Harper Vice President, European Operations Brett Byers Vice President, General Counsel and Investor Relations Products and Processes 8x8 has developed a Video Information Architecture (VIA) incorporating programmable integrated circuits (ICs) and compression/decompression algorithms (codecs) for audio/video communications. -

LIST of SECTION 13F SECURITIES ** PAGE 1 RUN TIME:09:57 Ivmool

RUN DATE:06/29/00 ** LIST OF SECTION 13F SECURITIES ** PAGE 1 RUN TIME:09:57 IVMOOl CUSIP NO. ISSUER NAME ISSUER DESCRIPTION STATUS B49233 10 7 ICOS VISION SYS CORP N V ORD B5628B 10 4 * LERNOUT & HAUSPIE SPEECH PRODS COM B5628B 90 4 LERNOUT & HAUSPIE SPEECH PRODS CALL B5628B 95 4 LERNOUT 8 HAUSPIE SPEECH PRODS PUT D1497A 10 1 CELANESE AG ORD D1668R 12 3 * DAIMLERCHRYSLER AG ORD D1668R 90 3 DAIMLERCHRYSLER AG CALL D1668R 95 3 DAIMLERCHRYSLER AG PUT F9212D 14 2 TOTAL FINA ELF S A WT EXP 080503 G0070K 10 3 * ACE LTD ORD G0070K 90 3 ACE LTD CALL G0070K 95 3 ACE LTD PUT GO2602 10 3 * AMDOCS LTD ORD GO2602 90 3 AMDOCS LTD CALL GO2602 95 3 AMDOCS LTD PUT GO2995 10 1 AMERICAN SAFETY INS GROUP LTD ORD G0352M 10 8 * AMWAY ASIA PACIFIC LTD COM DELETED G0352M 90 8 AMWAY ASIA PACIFIC LTD CALL DELETED G0352M 95 8 AMWAY ASIA PACIFIC LTD PUT DELETED GO3910 10 9 * ANNUITY AND LIFE RE HLDGS ORD GO3910 90 9 ANNUITY AND LIFE RE HLDGS CALL GO3910 95 9 ANNUITY AND LIFE RE HLDGS PUT GO4074 10 3 APEX SILVER MINES LTD ORD GO4074 11 1 APEX SILVER MINES LTD WT EXP 110402 GO4450 10 5 ARAMEX INTL LTD ORD GO5345 10 6 ASIA PACIFIC RES INTL HLDG LTD CL A G0535E 10 6 ASIA PACIFIC WIRE & CABLE CORP ORD GO5354 10 8 ASIACONTENT COM LTD CL A ADDED G1368B 10 2 BRILLIANCE CHINA AUTO HLDG LTD COM DELETED 620045 20 2 CENTRAL EUROPEAN MEDIA ENTRPRS CL A NEW G2107X 10 8 CHINA TIRE HLDGS LTD COM G2108N 10 9 * CHINADOTCOM CORP CL A G2108N 90 9 CHINADOTCOM CORP CALL G2lO8N 95 9 CHINADOTCOM CORP PUT 621082 10 5 CHINA YUCHAI INTL LTD COM 623257 10 1 COMMODORE HLDGS LTD ORD 623257 11 -

1 UNITED STATES SECURITIES and EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C

1 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 13F FORM 13F COVER PAGE Report for the Calendar Year or Quarter Ended: September 30, 2000 Check here if Amendment [ ]; Amendment Number: This Amendment (Check only one.): [ ] is a restatement. [ ] adds new holdings entries Institutional Investment Manager Filing this Report: Name: AMERICAN INTERNATIONAL GROUP, INC. Address: 70 Pine Street New York, New York 10270 Form 13F File Number: 28-219 The Institutional Investment Manager filing this report and the person by whom it is signed represent that the person signing the report is authorized to submit it, that all information contained herein is true, correct and complete, and that it is understood that all required items, statements, schedules, lists, and tables, are considered integral parts of this form. Person Signing this Report on Behalf of Reporting Manager: Name: Edward E. Matthews Title: Vice Chairman -- Investments and Financial Services Phone: (212) 770-7000 Signature, Place, and Date of Signing: /s/ Edward E. Matthews New York, New York November 14, 2000 - ------------------------------- ------------------------ ----------------- (Signature) (City, State) (Date) Report Type (Check only one.): [X] 13F HOLDINGS REPORT. (Check if all holdings of this reporting manager are reported in this report.) [ ] 13F NOTICE. (Check if no holdings reported are in this report, and all holdings are reported in this report and a portion are reported by other reporting manager(s).) [ ] 13F COMBINATION REPORT. (Check -

Issue 31 • Spring 2010 Magazine of the Maritime Union of New Zealand

The Issue 31 • Spring 2010 MaritimesMagazine of the Maritime Union of New Zealand ISSN 1176-3418 www.munz.org.nz The Maritimes | Spring 2010 | 1 TAX CHANGES GST hike hits family budget Tax Justice Labour Unions: campaign petition announces no National’s tax takes off GST on fruit and changes bad for The campaign to take GST off all food is vege policy workers gaining momentum with a mass petition effort on 1 - 2 October netting thousands of The Labour Party has announced a $270 Unions have rejected the National signatures. million policy for removing Goods and Government’s tax changes that came into A petition by the Tax Justice campaign is Services Tax (GST) from fresh fruit and effect on 1 October 2010. calling for the removal of GST off all food, to vegetables. The Council of Trade Unions says the be replaced by a tax on financial speculation. GST has gone up to 15% from the start of changes are unfair and will hit low income Thousands of signatures have been collected October 2010. people hard, and will also fail to drag New over the past few months. Labour’s announced policy to take GST off Zealand out of recession or improve long Campaign spokesperson Victor Billot says fresh fruit and vegetables would provide term economic prospects. by putting up GST to 15%, the National welcome relief to many families from GST, CTU economist Bill Rosenberg says the Government is making life harder for most a tax that hits people harder the lower tax changes, including hiking GST to 15% families to benefit a wealthy minority. -

US Vegan Climate

US Vegan Climate ETF Schedule of Investments April 30, 2021 (Unaudited) Shares Security Description Value COMMON STOCKS - 99.4% Administrative and Support and Waste Management and Remediation Services - 13.4% 1,675 Accenture plc - Class A $ 485,700 233 Allegion plc 31,311 107 Booking Holdings, Inc. (a) 263,870 293 Broadridge Financial Solutions, Inc. 46,479 317 Equifax, Inc. 72,666 352 Expedia Group, Inc. 62,033 70 Fair Isaac Corporation (a) 36,499 729 Fidelity National Financial, Inc. 33,257 214 FleetCor Technologies, Inc. (a) 61,572 782 Global Payments, Inc. 167,841 961 IHS Markit, Ltd. 103,384 5,607 Mastercard, Inc. - Class A 2,142,210 425 Moody's Corporation 138,852 212 MSCI, Inc. 102,983 3,091 PayPal Holdings, Inc. (a) 810,738 491 TransUnion 51,354 8,745 Visa, Inc. - Class A 2,042,482 6,653,231 Construction - 0.9% 890 DR Horton, Inc. 87,478 1,956 Johnson Controls International plc 121,937 705 Lennar Corporation - Class A 73,038 19 NVR, Inc. (a) 95,344 682 PulteGroup, Inc. 40,320 396 Sunrun, Inc. (a) 19,404 437,521 Finance and Insurance - 14.1% 1,735 Aflac, Inc. 93,222 40 Alleghany Corporation (a) 27,159 797 Allstate Corporation 101,060 969 Ally Financial, Inc. 49,855 1,588 American Express Company 243,520 2,276 American International Group, Inc. 110,272 314 Ameriprise Financial, Inc. 81,138 657 Anthem, Inc. 249,259 596 Aon plc - Class A 149,858 1,025 Arch Capital Group, Ltd. (a) 40,703 496 Arthur J. -

U.S. Technology, Media & Telecom Industry

Technology, Media & Telecom Industry Update May 2012 Member FINRA/SIPC www.harriswilliams.com Table of Contents Technology, Media & Telecom What We've Been Reading…………………………………………………………………………………………1 Bellwethers……………………………………………………………………………………………2 TMT Public Market Trading Statistics………………………………………………………………………..…………………..3 Recent TMT M&A Activity…………………………………………………………………………………………….4 Recent U.S. TMT Initial Public Offerings………………………………………………………………………….………………...………..5 Public and M&A Market Overview by Sector Data and Information Services………………………………………………………………..…………..6 Financial Technology…………………………………………………………………………8 Internet & Digital Media……………………………………………………..…………………..10 IT and Tech-Enabled Services………………………………………………………………..13 Software – Application…………………………………………………….…………………..15 Software – Infrastructure……………………………………………………..…………………..18 Software – SaaS……………………………………………………………………………………………………..20 Tech Hardware……………………………………………………………………..…………………..22 Telecom………………………………………………………………………………………………..25 Selected HW&Co. TMT Transactions…………………………………………………………………………………………..28 TMT Group Overview and Disclosures…………………………………………………………………………………………..29 Note: All market data in the following materials is as of April 30, 2012. What We’ve Been Reading How The Bush Tax Cuts Could Lead To A Crazy Year For M&A Business Insider 4/30/2012 An increased amount of M&A activity is expected in the remainder of 2012 as potential changes in the capital gains tax policies are motivating firms to exit investments before the end of the year when the Bush Tax Cuts expire. -

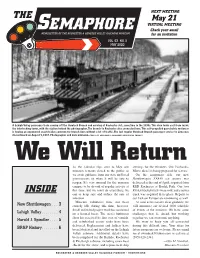

Inside the Interlocking Tower, with the Station Behind the Photographer

NEXT MEETING: May 21 VIRTUAL MEETING Check your email for an invitation VOL. 63 NO. 5 MAY 2020 A Lehigh Valley passenger train coming off the Hemlock Branch and arriving at Rochester Jct., sometime in the 1930s. This view looks east from inside the interlocking tower, with the station behind the photographer. The branch to Rochester also connected here. This self-propelled gas-electric motorcar is towing an unpowered coach trailer, common for branch lines without a lot of traffic. The last regular Hemlock Branch passenger service to Lima was discontinued on August 9, 1937. Photographer and date unknown. COURTESY ANTHRACITE RAILROADS HISTORICAL SOCIETY We Will Return As the calendar flips over to May, our awnings for the windows. Our Fairbanks- museum remains closed to the public as Morse diesel is being prepared for service. we await guidance from our state and local On the equipment side, our new governments on when it will be safe to Shuttlewagon SX430 car mover was reopen. It’s very unusual for the museum delivered at the end of April, acquired from campus to be devoid of regular activity at RED Rochester at Kodak Park. Our two INSIDE this time, but we must do everything we RG&E bucket trucks were sold, and a newer can to keep safe and reduce the rate of truck was acquired in its place. Repairs to infection. our Jackson Tamper are continuing as well. New Shuttlewagon ...3 Museum volunteers have not been As soon as we receive clear guidance, we entirely idle during this time, however. will announce our revised 2020 schedule Lehigh Valley ........4 Small individual project work has continued of events at the museum. -

Index to Dickson Gregory Collection of Drawings and Photographs of Wrecked Or Disabled Ships, 1853-1973

Index to Dickson Gregory collection of drawings and photographs of wrecked or disabled ships, 1853-1973 Ship Name Vol. and page Classification Year TonnageAdditional Information from volumes Other Names Abertaye 18.36 steam ship Wrecked at Land's End, South America. Abertaye 18.25 steam ship A double wreck "South America" and "Abertaye" on the Cornish Coast. Admella 1.49 steam ship 1858 400 Built 1858. Wrecked near Cape Northumberland SA 6th August 1859, 70 lives lost. Admella 15.26* steam ship 1858 400 Wreck in 1859. Admella 12.27* steam ship 1858 400 Wrecked on Carpenter Rocks near Cape Northumberland 6 August 1859. Over 70 lives lost. Admella 1.49 steam ship 1858 400 Wreck of near Cape Northumberland SA 6th August 1859 70 lives lost. Admella 18.52a steam ship 1858 400 Wreck near Cape Northumberland, 6 August 1859. Over 70 lives lost. Admella 19.54 steam ship 1858 400 Wrecked near Cape Northumberland, SA, 6 August 1859. Admiral Cecile 3.77 ship 1902 2695 Built at Rouen 1902. Burnt 25th January 1925 in the canal de la Martiniere while out of commission. Photograped at Capetown Docks. Admiral Karpfanger 23.152c 4 mast 2754 The ship feared to be missing at this time. She had Ex "L'Avenir". barque on board a cargo of wheat from South Australia to Falmouth, Plymouth. Admiral Karpfanger 23.132c 4 mast Went missing off Cape Horn with a cargo of wheat. Ex "L'Avenir". barque Adolf Vinnen 18.14 5 mast Wrecked near The Lizard 1923. schooner Adolph 18.34 4 mast Wrecks of four masted "Adolph" near masts of barque barque "Regent Murray". -

The Log Quarterly Journal of the Nautical Association of Australia Inc

THE www.nautical.asn.au LOG QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF THE NAUTICAL ASSOCIATION OF AUSTRALIA INC. VOL. 53, NO. 1, ISSUE 219 - NEW SERIES 2020 Tambua (3,566/1938) arriving Sydney July 1963 (J.Y.Freeman) Tambua was built for the Colonial Sugar Refining Co. Ltd, Sydney, by Caledon Ship Building & Engineering Co., Dundee, in 1938, having been completed in July of that year. She was designed to carry bagged sugar in the holds and molasses in wing tanks. With a crew of 37, she traded Sydney, North Queensland ports, Fiji and New Zealand, back loading building materials, farming equipment, foodstuffs, railway tracks etc. She was renamed Maria Rosa when sold in 1968 and went to scrap under that name at Kaohsiung where she arrived 7 January 1973. PRINT POST PUBLICATION NUMBER 100003238 ISSN 0815-0052. All rights reserved. Across 25/26 January the amphibious ship HMNZS Canterbury attended the Ports of Auckland SeePort Festival 2020. Then on 28 January, in company with HMNZ Ships Wellio and Haa, the ship began a series of training and work-up exercises after the Christmas break. After three years of the design and build effort by HHI at the Ulsan shipyard, the new tanker Aotaroa began sea trials off the South Korean coast on 10 December ahead of her upcoming journey home to New Zealand. On 3 December the patrol vessel HMNZS Wellio in company with the Tuia 250 flotilla arrived in Wellington Harbour, including HMB Endeavour, Sirit of New Zeaand and a waka hourua. The national event celebrated New Zealand‟s voyaging heritage, and mark 250 years since the first onshore encounters between Māori and Captain James Cook and the crew of HMB Endeavour. -

REMEMBERING SEAFARERS. the (Missing) History of New

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. REMEMBERING SEAFARERS The (Missing) History of New Zealanders employed in the Mercantile Marine during World War 1 A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History at Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand Philip R. Lascelles 2014 Remembering Seafarers A BSTRACT The story of the New Zealand men and women who were employed in the Mercantile Marine during World War 1 is absent from the historiography. This thesis contends that this workforce of New Zealanders existed, was substantial in number and that their human stories are missing from historiography despite there being extensive wartime stories to tell. A workforce of New Zealand merchant seafarers existed during World War 1 and is definable and recognisable as a group. Each individual within this group is not easily identifiable because detailed and completed records of their identity and service were never centrally maintained. New Zealand maritime and World War 1 histories have not addressed the seafarers’ intimate human stories and have instead focus on either Naval or industry stakeholder’s organisational history of the war period. This is clearly evident from a detailed review of relevant material published during the century since the declaration of World War 1 in 1914. The crew employed on the Union Steam Ship Company’s twin screw steamship Aparima provide a small but enlightening example of the human stories that are absent. -

Company Vendor ID (Decimal Format) (AVL) Ditest Fahrzeugdiagnose Gmbh 4621 @Pos.Com 3765 0XF8 Limited 10737 1MORE INC

Vendor ID Company (Decimal Format) (AVL) DiTEST Fahrzeugdiagnose GmbH 4621 @pos.com 3765 0XF8 Limited 10737 1MORE INC. 12048 360fly, Inc. 11161 3C TEK CORP. 9397 3D Imaging & Simulations Corp. (3DISC) 11190 3D Systems Corporation 10632 3DRUDDER 11770 3eYamaichi Electronics Co., Ltd. 8709 3M Cogent, Inc. 7717 3M Scott 8463 3T B.V. 11721 4iiii Innovations Inc. 10009 4Links Limited 10728 4MOD Technology 10244 64seconds, Inc. 12215 77 Elektronika Kft. 11175 89 North, Inc. 12070 Shenzhen 8Bitdo Tech Co., Ltd. 11720 90meter Solutions, Inc. 12086 A‐FOUR TECH CO., LTD. 2522 A‐One Co., Ltd. 10116 A‐Tec Subsystem, Inc. 2164 A‐VEKT K.K. 11459 A. Eberle GmbH & Co. KG 6910 a.tron3d GmbH 9965 A&T Corporation 11849 Aaronia AG 12146 abatec group AG 10371 ABB India Limited 11250 ABILITY ENTERPRISE CO., LTD. 5145 Abionic SA 12412 AbleNet Inc. 8262 Ableton AG 10626 ABOV Semiconductor Co., Ltd. 6697 Absolute USA 10972 AcBel Polytech Inc. 12335 Access Network Technology Limited 10568 ACCUCOMM, INC. 10219 Accumetrics Associates, Inc. 10392 Accusys, Inc. 5055 Ace Karaoke Corp. 8799 ACELLA 8758 Acer, Inc. 1282 Aces Electronics Co., Ltd. 7347 Aclima Inc. 10273 ACON, Advanced‐Connectek, Inc. 1314 Acoustic Arc Technology Holding Limited 12353 ACR Braendli & Voegeli AG 11152 Acromag Inc. 9855 Acroname Inc. 9471 Action Industries (M) SDN BHD 11715 Action Star Technology Co., Ltd. 2101 Actions Microelectronics Co., Ltd. 7649 Actions Semiconductor Co., Ltd. 4310 Active Mind Technology 10505 Qorvo, Inc 11744 Activision 5168 Acute Technology Inc. 10876 Adam Tech 5437 Adapt‐IP Company 10990 Adaptertek Technology Co., Ltd. 11329 ADATA Technology Co., Ltd. -

Loss of Rail Competition As an Issue in the Proposed Sale of Conrail to Norfolk Southern: Valid Concern Or Political Bogeyman

Cleveland State Law Review Volume 34 Issue 3 Article 6 1986 Loss of Rail Competition as an Issue in the Proposed Sale of Conrail to Norfolk Southern: Valid Concern or Political Bogeyman Mark D. Perreault Nancy S. Fleischman Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clevstlrev Part of the Business Organizations Law Commons, and the Transportation Law Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Mark D. Perreault & Nancy S. Fleischman, Loss of Rail Competition as an Issue in the Proposed Sale of Conrail to Norfolk Southern: Valid Concern or Political Bogeyman, 34 Clev. St. L. Rev. 413 (1985-1986) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cleveland State Law Review by an authorized editor of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LOSS OF RAIL COMPETITION AS AN ISSUE IN THE PROPOSED SALE OF CONRAIL TO NORFOLK SOUTHERN: VALID CONCERN OR POLITICAL BOGEYMAN? MARK D. PERREAULT* NANCY S. FLEISCHMAN** 1. INTRODUCTION ......... ..................................... 414 II. PRESERVATION OF RAIL-RAIL COMPETITION AS A CONSIDERATION IN RAIL CONSOLIDATIONS ............................... 414 A . Prior to 1920 ................................. 414 B . 1920 - 1940 .................................. 418 C. 1940 - 1980 .................................. 421 D . 1980 - Present ................................ 425 Ill. PRESERVATION OF RAIL-RAIL COMPETITION AS A CONSIDERATION IN THE FORMATION OF CONRAIL AND SUBSEQUENT DETERMINATION TO SELL CONRAIL ........ ........................................ 428 A. 1970's Congressional Response to the Penn Central and Other Railroad Bankruptcies ..................... 428 B. Foundation of Initial CongressionalPolicy ........... 429 C. Implementing the Policy ......................... 432 D.