Catholic Secondary School Principals' Perceptions of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title: the Distribution of an Illustrated Timeline Wall Chart and Teacher's Guide of 20Fh Century Physics

REPORT NSF GRANT #PHY-98143318 Title: The Distribution of an Illustrated Timeline Wall Chart and Teacher’s Guide of 20fhCentury Physics DOE Patent Clearance Granted December 26,2000 Principal Investigator, Brian Schwartz, The American Physical Society 1 Physics Ellipse College Park, MD 20740 301-209-3223 [email protected] BACKGROUND The American Physi a1 Society s part of its centennial celebration in March of 1999 decided to develop a timeline wall chart on the history of 20thcentury physics. This resulted in eleven consecutive posters, which when mounted side by side, create a %foot mural. The timeline exhibits and describes the millstones of physics in images and words. The timeline functions as a chronology, a work of art, a permanent open textbook, and a gigantic photo album covering a hundred years in the life of the community of physicists and the existence of the American Physical Society . Each of the eleven posters begins with a brief essay that places a major scientific achievement of the decade in its historical context. Large portraits of the essays’ subjects include youthful photographs of Marie Curie, Albert Einstein, and Richard Feynman among others, to help put a face on science. Below the essays, a total of over 130 individual discoveries and inventions, explained in dated text boxes with accompanying images, form the backbone of the timeline. For ease of comprehension, this wealth of material is organized into five color- coded story lines the stretch horizontally across the hundred years of the 20th century. The five story lines are: Cosmic Scale, relate the story of astrophysics and cosmology; Human Scale, refers to the physics of the more familiar distances from the global to the microscopic; Atomic Scale, focuses on the submicroscopic This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. -

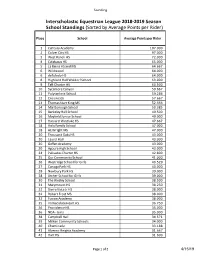

Schools Average Points Per Ride

Standing Interscholastic Equestrian League 2018-2019 Season School Standings (Sorted by Average Points per Rider) Place School Average Points per Rider 1 Century Academy 107.000 2 Culver City HS 97.000 3 West Ranch HS 72.000 4 Calabasas HS 65.000 5 La Reina HS and MS 64.667 6 Wildwood 64.000 6 deToledo HS 64.000 8 Highland Hall Waldorf School 63.000 9 Taft Charter HS 60.500 10 Sycamore Canyon 59.667 11 Polytechnic School 59.286 12 Crossroads 57.667 13 Thomas Starr King MS 52.333 14 Marlborough School 50.385 15 Berkeley Hall School 49.500 16 Mayfield Junior School 49.000 17 Harvard-Westlake HS 47.667 18 Holy Family School 47.000 18 AE Wright MS 47.000 20 Thousand Oaks HS 43.000 20 Laurel Hall 43.000 20 Geffen Academy 43.000 20 Agoura High School 43.000 24 Palisades Charter HS 42.800 25 Our Community School 41.000 26 Westridge School for Girls 40.529 27 Canoga Park HS 40.000 28 Newbury Park HS 39.000 28 Archer School for Girls 39.000 30 The Wesley School 38.500 31 Marymount HS 38.250 32 Sierra Vista Jr HS 38.000 32 Robert Frost MS 38.000 32 Fusion Academy 38.000 35 Immaculate Heart HS 36.750 36 Providence HS 35.000 36 NDA - Girls 35.000 38 Campbell Hall 34.571 39 Milken Community Schools 34.000 40 Chaminade 33.188 41 Alverno Heights Academy 31.667 42 Hart HS 31.600 Page 1 of 2 4/15/19 Standing Interscholastic Equestrian League 2018-2019 Season School Standings (Sorted by Average Points per Rider) Place School Average Points per Rider 43 Burbank HS 30.667 44 Windward 30.000 44 Canyon HS 30.000 44 Beverly Vista School 30.000 47 La Canada HS 29.727 48 Saugus HS 28.000 49 San Marino HS 27.000 50 St. -

Archdiocese of Los Angeles Catholic Directory 2020-2021

ARCHDIOCESE OF LOS ANGELES CATHOLIC DIRECTORY 2020-2021 Mission Basilica San Buenaventura, Ventura See inside front cover 01-FRONT_COVER.indd 1 9/16/2020 3:47:17 PM Los Angeles Archdiocesan Catholic Directory Archdiocese of Los Angeles 3424 Wilshire Boulevard Los Angeles, CA 90010-2241 2020-21 Order your copies of the new 2020-2021 Archdiocese of Los Angeles Catholic Directory. The print edition of the award-winning Directory celebrates Mission San Buenaventura named by Pope Francis as the first basilica in the Archdiocese. This spiral-bound, 272-page Directory includes Sept. 1, 2020 assignments – along with photos of the new priests and deacons serving the largest Archdiocese in the United States! The price of the 2020-21 edition is $30.00 (shipping included). Please return your order with payment to assure processing. (As always, advertisers receive one complimentary copy, so consider advertising in next year’s edition.) Directories are scheduled to begin being mailed in October. _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ Please return this portion with your payment REG Archdiocese of Los Angeles 2020-2021 LOS ANGELES CATHOLIC DIRECTORY ORDER FORM YES, send the print version of the 2020-21 ARCHDIOCESE OF LOS ANGELES CATHOLIC DIRECTORY at the flat rate of $30.00 each. Please return your order with payment to assure processing. -

Archdiocese of Los Angeles

Clerical Sexual Abuse in the Archdiocese of Los Angeles AndersonAdvocates.com • 310.357.2425 Attorney Advertising “For many of us, those earlier stories happened someplace else, someplace away. Now we know the truth: it happened everywhere.” ~ Pennsylvania Grand Jury Report 2018 AndersonAdvocates.com • 310.357.2425 2 Attorney Advertising Table of Contents Purpose & Background ...........................................................................................9 History of the Archdiocese of Los Angeles ...........................................................12 Los Angeles Priests Fleeing the Jurisdiction: The Geographic Solution ....................................................................................13 “The Playbook for Concealing the Truth” ..........................................................13 Map ........................................................................................................................16 Archdiocese of Los Angeles Documents ...............................................................17 Those Accused of Sexual Misconduct in the Archdiocese of Los Angeles ..... 38-125 AndersonAdvocates.com • 310.357.2425 3 Attorney Advertising Clerics, Religious Employees, and Volunteers Accused of Sexual Misconduct in the Archdiocese of Los Angeles Abaya, Ruben V. ...........................................39 Casey, John Joseph .......................................49 Abercrombie, Leonard A. ............................39 Castro, Willebaldo ........................................49 Aguilar-Rivera, -

WELCOME! Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary Church 2640 E

WELCOME! Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary Church 2640 E. Orange Grove Blvd., Pasadena, CA 91107 www.abvmpasadena.org Congratulations To Our Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary School Eighth Grade Graduates 2019 ABVM CLASS OF 2019 SCHOOLS THEY WILL ATTEND Casey Danielle Aghili Ulysses Joseph Hill Gabriella Carolina Prado St. Lucy’s Priory High Mayfield Senior School Kaylie Leilani Armas Cailene Ito Fiona Grace Snashall School Arcadia High School Levon Arutunian Jace Cameron Delmundo Elijah Andrew Cupples Flintridge Sacred Heart Ramona Convent Second- David Panganiban Bautista Izuno Soto Alexander Academy ary School Lucas Kai Sabater Benitez Alexi Lopez James Varela St. Francis High School Los Angeles County High Sarah Elise Brenes Erin Nicole Marsh Rubi G. Vargas California School of the Arts School for the Arts James David Clapp Elizabeth McCarthy Nicole Ana Werner Loyola High School Califor- St. John Paul II STEM Kaylin Annette Compton Sophia Adriana Mercurio nia School of the Arts Academy Anthony Alberto Cruz Sara Mirzayev Immaculate Heart High La Salle College Prepara- Ryan Allen Doerfler Liv Montenegro School tory High School Angela Therese G. Echaorre Alexandra Mullis Cathedral High School Saint Monica Academy Tyler Joseph Ferrante Aidan Patrick O’Connor Damien High School San Gabriel Mission High Victor Rusty Gonzaga Jonathan Domingo Ohanian Los Angeles County High Lorenzo Gumabao-Ravago Adam Isaac Pavon School for the Arts Pentecost Sunday Office Hours: Mass Schedule June 9, 2019 Monday-Friday Saturday Vigil: Pastor: Business Manager: 9:00AM-Noon & 5:00PM Fr. Michael Ume Kathy Tracy 1:00-4:00PM Sunday: Pastoral Associate: School Principal: (626)792-1343 7:30AM - 9:00AM Sr. -

990-PF and Its Instructions Is at Www

l efile GRAPHIC p rint - DO NOT PROCESS As Filed Data - DLN: 93491310007114 Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990 -PF or Section 4947 ( a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation 0- Do not enter Social Security numbers on this form as it may be made public . By law, the 2013 IRS cannot redact the information on the form. Department of the Treasury 0- Information about Form 990-PF and its instructions is at www. irs.gov /form990pf . Internal Revenue Service For calendar year 2013 , or tax year beginning 01 - 01-2013 , and ending 12-31-2013 Name of foundation A Employer identification number DAN MURPHY FOUNDATION 95-6046963 Number and street ( or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address ) Room / suite U ieiepnone number ( see instructions) 800 WEST SIXTH STREET (213) 623-3120 City or town, state or province , country, and ZIP or foreign postal code C If exemption application is pending, check here F LOS ANGELES, CA 90017 G Check all that apply r'Initial return r'Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here F r-Final return r'Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, r Address change r'Name change check here and attach computation E If private foundation status was terminated H Check type of organization Section 501( c)(3) exempt private foundation und er section 507 ( b )( 1 )( A ), c hec k here F_ Section 4947( a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust r'Other taxable private foundation I Fair market value of all assets at end J Accounting method F Cash F Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60 - month termination of year (from Part II, col. -

2018 Annual Statement of Accountability Catholic

2018 ANNUAL STATEMENT OF ACCOUNTABILITY CATHOLIC COMMUNITY FOUNDATION of LOS ANGELES MISSION STATEMENT CHAIRMAN’S LETTER Dear Friends and Clients of CCF-LA, As we close the books on our fourth great year, we are particularly pleased to mark THE CATHOLIC COMMUNITY FOUNDATION milestones in both growth of assets under management and growth of grants. OF LOS ANGELES EMPOWERS CHARITABLE One of our primary goals was to broaden the boundaries of our professional INDIVIDUALS AND ORGANIZATIONS ACROSS philanthropy management to embrace the entire three-county region of the Archdiocese of Los Angeles. This was accomplished through outreach to more CULTURES AND GENERATIONS THROUGH individuals and organizations in this vast area. At year-end we had $235.7 million PROFESSIONAL PHILANTHROPY MANAGEMENT managed in 177 funds. SOLUTIONS THAT ALLOW CLIENTS TO Most notably, in March, we passed the $100 million mark in DEVELOP AND SUSTAIN THEIR PHILANTHROPY grants made and ended the year having granted more than $144 million since inception. IN SUPPORT OF CATHOLIC VALUES. Despite some clouds surrounding our Church, our donors redoubled their commitment to the foundation, understanding that a “call to action” is an integral part of supporting the good works that are the foundation of our Church. We welcomed Delia M. Roges and Carrie Shea Tilton to our Board, bringing our members to 13. Rosalia S. Nolan completed her term as a founding director with our gratitude. I am grateful to all of our Board members, staff, contractors, volunteers, and clients for their continuing faith and contributions to the Catholic Community Foundation of Los Angeles. Sincerely, William M. -

2016 Mcdonald's All American Games Nominees

2016 McDonald's All American Games Nominees Last Updated January 5 BOYS NOMINEES ALABAMA First Last School Name City State Josh Langford Madison Academy Madison Alabama Seth Swalve Cullman High School Cullman Alabama ARIZONA First Last School Name City State Andrew Ekmark Phoenix Country Day School Paradise Valley Arizona Mitchell Lightfoot Gilbert Christian High School Gilbert Arizona ARKANSAS First Last School Name City State Malik Monk Bentonville High School Bentonville Arkansas CALIFORNIA First Last School Name City State Ben Kone Archbishop Mitty High School San Jose California Brandon Lawrence Moreau Catholic High School Hayward California Bryce Peters Damien High School La Verne California Cameron Patterson Bishop O'Dowd High School Oakland California Cameron Williams Redondo Union High School Redondo Beach California Christian Ellis Modesto Christian High School Modesto California Christian Terrell Sacramento Charter High School Sacramento California Colin Slater Immanuel High School Reedley California D'Anthony Melton Crespi Carmelite High School Los Angeles California Daron Henson Cathedral High School Los Angeles California Devearl Ramsey Sierra Canyon High School Chatsworth California Dikymbe Martin John W. North High School Riverside California Donovan Mitchell Buchanan High School Clovis California Drew Buggs Long Beach Poly High School Long Beach California Eyassu Worku Los Alamitos High School Los Alamitos California Garrett Carter Etiwanda High School Etiwanda California Henry Welsh Loyola High School Los Angeles California -

Level 3 2013 National Spanish Examination

Students who earned Premios de Bronce - Level 3 2013 National Spanish Examination NOTE: The information in the columns below was extracted from the information section which students completed on the Achievement portion of the National Spanish Examination. 99 - No Chapter Kristina Abicca Etowah High School Larrotta GA Regina Acosta Temple High School Gasper TX Kevin Aguilar Williams Preparatory Salinas TX Ahmed Ahad Canterbury School Veale FL Mazin Ahmad EC Glass High School Hodges VA Providence Career Technical Isaura Alavrez Mendiburu RI School Jesus Alberto Franklin High School Noguera NJ Hannah Aliazzi Hawken School Komocki OH Hanley Allen Mount de Sales Academy Salazar MD Benjamin Anderson penfield high school teeter NY Claire Anderson Cardinal Ritter High School Hill IN Caroline Angles St. Teresa's Academy.org Gargallo MO Isabella Aquino Mount de Sales Academy Salazar MD Brooke Arnold Cherry Creek High School Jones CO Saint John's Preparatory Ellen Arnold Talic MN School Jacqueline Arnold Mount de Sales Academy Salazar MD Lindsey Arrillaga Mountain View High School Morgan CA Abby Austin PK Yonge DRS Santiago FL John Austin Westlake High School Jimeno TX Aron Aziz Columbus Academy Larson OH Pittsford Mendon High David Azzara Ebert NY School Ben Bailey Webb School of Knoxville Brown TN Daniel Bailey Canterbury School Veale FL Avery Baker The Hockaday School Kelly TX Nicolás Baker Central Catholic High School Compean-Avila TX Liberal Arts and Science Jacob Baldwin Czaplinski TX Academy High School Chelsea Banawis LASA High School browne TX Fayetteville-Manlius High Mary Barger Tzetzis NY School Jordan Barham Woodstock High School Larrotta GA Benjamin Barmdan Mountain View High School Roach CA Central Columbia High Rebecca Barnes Taylor PA School St. -

Citrus College Student Achievement Awards Key of Knowledge

Achievement Awards KEY OF KNOWLEDGE RECIPIENTS Citrus Community College District DESTINY MIRANDA CONTRERAS Board of Trustees Major: Sociology, Administration of Justice Dr. Patricia A. Rasmussen President Transfer Institution: University of California, Los Angeles Glendora and portions of High School: Upland High School San Dimas Representative Destiny began her journey at Citrus College in 2015 when she enrolled in Ms. Mary Ann Lutz Vice President the cosmetology program. In 2018, she decided to return with the goal Monrovia/Bradbury and portions of earning an associate degree and transferring to a four-year university. of Duarte Representative “I didn’t let my previous failures in high school determine how I was going to strive for greatness in Ms. Laura Bollinger my college career. It is truly something I wanted for myself, and I made it happen regardless of the Clerk/Secretary circumstances and previous roadblocks,” she says. In the future, Destiny plans on attending a nursing Claremont and portions of Pomona and La Verne program in the hope of becoming a registered nurse. Representative Dr. Edward C. Ortell Member Duarte and portions of Azusa, Monrovia, Arcadia, Covina and Irwindale Representative Dr. Anthony Contreras MISSAEL AYRALDO CUEVAS CHAVEZ Member Azusa and portions of Duarte Major: Mechanical Engineering Representative Transfer Institution: Cal Poly Pomona Miss Taylor McNeal High School: Azusa High School Student Trustee Missael enrolled at Citrus College after serving in the U.S. Marine Corps. He considers veterans’ counselor David Rodriguez and Veterans Success Center Dr. Geraldine M. Perri Superintendent/President Director Maria Buffo as the two greatest factors in his successful transition from a military mindset toward an academic mindset. -

NISCA All-America Swimming and Diving 2018 - 2019

NISCA All-America Swimming and Diving 2018 - 2019 https://www.niscaonline.org/aalists/2019/allam19.html 2018-19 NISCA Swimming and Diving All America All-America Certificates will be mailed directly to athletes that achieved "Top 100" performances in all events. Please check events, times and spelling for accuracy. Boys Swimming contact: [email protected] Girls Swimming contact: [email protected] Boys and Girls Diving contact: [email protected] National Interscholastic Swimming Coaches Association 2018-2019 All-America Swimmers and Divers 200 Med Rel 200 Free 200 Ind Med 50 Free Dive 100 Fly Boys Events in Yards 100 Free 500 Free 200 Fr Rel 100 Back 100 Breast 400 Fr Rel 200 Med Rel 200 Free 200 Ind Med 50 Free Dive 100 Fly Girls Events in Yards 100 Free 500 Free 200 Fr Rel 100 Back 100 Breast 400 Fr Rel Statistics All-America Final Standings by State and Gender 1 of 1 3/8/2020, 2:09 PM https://www.niscaonline.org/AALists/2019/b200mrel19.htm 2018-19 NISCA Boys High School Swimming All-America 200 Yard Medley Relay - Automatic AA 1:33.53 NATIONAL RECORD: 1:27.74 - The Baylor School (Luke Kaliszak, Dustin Tynes, Sam McHugh and Chri Chattanooga, TN - February 14, 2014 7/8/2019 Place Time Swimmers (Gr) School City State 1 1:28.48 Carson Foster (11), Jake Foster (12), Ansel Froass (11), Elliott Carl (12) Sycamore High School Cincinnati OH 2 1:28.94 Nate Buse (11), Scott Sobolewski (11), Jean-Pierre Khouzam (11), Owen Taylor (10) St. Xavier High School Cincinnati OH 3 1:29.21 Wyatt Davis (10), Ryan Malicki (9 ), Griffin -

School Profile 2019-2020

MAYFIELD SENIOR SCHOOL of the Holy Child Jesus School Profile2019-2020 overview academic program Mayfield Senior School, founded in 1931 Graduation Requirements by the Society of the Holy Child Jesus, is a English (4); Theology (4); Mathematics (3); Social Studies (3); World Languages (3 units of Catholic, independent, college preparatory one language or 2 units each of two different languages); Laboratory Science (3); Fitness & school for young women grades 9–12. Wellness (2); Fine Arts (1); and community service. Enrolling from 68 different middle schools, Grading Mayfield Senior School students arrive on Grading is based on an A-F scale. C is a campus with diverse academic preparation college recommending grade; D is the lowest and varied perspectives. More than 30% of GPA acceptable grade. Any student receiving a grade students receive financial assistance. below C- in a class is counseled to repeat the Mayfield does not list a GPA on student Philosophy course in summer school. Mayfield’s GPA transcripts, as we strongly believe one number cannot adequately measure a Mayfield fosters each student’s intellectual, includes all courses in which a letter grade is student’s potential for success. For college spiritual, artistic, emotional and physical given and factors in pluses and minuses (A+ is admissions purposes, we provide a GPA gifts, enabling each to make a meaningful not given). We do not assign class rank. contribution to society. The measure of a through the counselor report. Mayfield education goes beyond cumulative Advanced Placement and Honors Courses MID 50% grade point averages, test scores and In addition to a rigorous college preparatory GPA RANGE academic success.