Christopher Hitchens and the Public Intellectual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Leftist Case for War in Iraq •fi William Shawcross, Allies

Fordham International Law Journal Volume 27, Issue 6 2003 Article 6 Vengeance And Empire: The Leftist Case for War in Iraq – William Shawcross, Allies: The U.S., Britain, Europe, and the War in Iraq Hal Blanchard∗ ∗ Copyright c 2003 by the authors. Fordham International Law Journal is produced by The Berke- ley Electronic Press (bepress). http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ilj Vengeance And Empire: The Leftist Case for War in Iraq – William Shawcross, Allies: The U.S., Britain, Europe, and the War in Iraq Hal Blanchard Abstract Shawcross is superbly equipped to assess the impact of rogue States and terrorist organizations on global security. He is also well placed to comment on the risks of preemptive invasion for existing alliances and the future prospects for the international rule of law. An analysis of the ways in which the international community has “confronted evil,” Shawcross’ brief polemic argues that U.S. President George Bush and British Prime Minister Tony Blair were right to go to war without UN clearance, and that the hypocrisy of Jacques Chirac was largely responsible for the collapse of international consensus over the war. His curious identification with Bush and his neoconservative allies as the most qualified to implement this humanitarian agenda, however, fails to recognize essential differences between the leftist case for war and the hard-line justification for regime change in Iraq. BOOK REVIEW VENGEANCE AND EMPIRE: THE LEFTIST CASE FOR WAR IN IRAQ WILLIAM SHAWCROSS, ALLIES: THE U.S., BRITAIN, EUROPE, AND THE WAR IN IRAQ* Hal Blanchard** INTRODUCTION In early 2002, as the war in Afghanistan came to an end and a new interim government took power in Kabul,1 Vice President Richard Cheney was discussing with President George W. -

Is God Great?

IS GOD GREAT? CHRISTOPHER HITCHENS AND THE NEW ATHEISM DEBATE Master’s Thesis in North American Studies Leiden University By Tayra Algera S1272667 March 14, 2018 Supervisor: Dr. E.F. van de Bilt Second reader: Ms. N.A. Bloemendal MA 1 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1 – The New Atheism Debate and the Four Horsemen .............................................. 17 Chapter 2 – Christopher Hitchens ............................................................................................ 27 Conclusion .............................................................................................................................. 433 Bibliography ........................................................................................................................... 455 2 3 Introduction “God did not make us, we made God” Christopher Hitchens (2007) "What can be asserted without evidence can be dismissed without evidence" Christopher Hitchens (2003) “Religion is violent, irrational, intolerant, allied to racism and tribalism and bigotry, invested in ignorance and hostile to free inquiry, contemptuous of women and coercive toward children." Christopher Hitchens (2007) These bold statements describe the late Christopher Hitchens’s views on religion in fewer than 50 words. He was a man of many words, most aimed at denouncing the role of religion in current-day societies. Religion is a concept that is hard -

The Left and the Algerian Catastrophe

THE LEFT AND THE ALGERIAN CATASTROPHE H UGH R OBERTS n explaining their sharply opposed positions following the attacks on the IWorld Trade Center and the Pentagon on 11 September 2001, two promi- nent writers on the American Left, Christopher Hitchens and Noam Chomsky, both found it convenient to refer to the Algerian case. Since, for Hitchens, the attacks had been the work of an Islamic fundamentalism that was a kind of fascism, he naturally saw the Algerian drama in similar terms: Civil society in Algeria is barely breathing after the fundamentalist assault …We let the Algerians fight the Islamic-fascist wave without saying a word or lending a hand.1 This comment was probably music to the ears of the Algerian government, which had moved promptly to get on board the US-led ‘coalition’ against terror, as Chomsky noted in articulating his very different view of things: Algeria, which is one of the most murderous states in the world, would love to have US support for its torture and massacres of people in Algeria.2 This reading of the current situation was later supplemented by an account of its genesis: The Algerian government is in office because it blocked the democratic election in which it would have lost to mainly Islamic-based groups. That set off the current fighting.3 The significance of these remarks is that they testify to the fact that the Western Left has not addressed the Algerian drama properly, so that Hitchens and Chomsky, neither of whom pretend to specialist knowledge of the country, have THE LEFT AND THE ALGERIAN CATASTROPHE 153 not had available to them a fund of reliable analysis on which they might draw. -

Harrison Stetler Thesis

“A skilled surgeon presiding at the birth of a new culture”: Christopher Lasch on the Politics of Post-Industrial Society Senior Thesis by Harrison Stetler Advisor: Professor Rebecca Kobrin Second Reader: Professor Casey Blake April 2016 Department of History Columbia University 16, 520 Words Acknowledgements: Writing this thesis has been an extraordinarily trying and rewarding experience, which I would not have been able to complete without an inordinate amount of help and support from friends and family. I owe a great debt to all my fellow students and to Professor Kobrin for providing an immense amount of support over the past year. I would also like to thank Professor Blake for guiding me through this study of Lasch’s thought. Likewise, I owe a debt of gratitude to a number of other teachers—Professors Mark Mazower, Adam Tooze, Mark Lilla, and Nicholas Dames, in particular—who have participated in a number of smaller yet indispensible ways throughout this long process. For letting me rant incessantly about Christopher Lasch, I am not sure whether I should apologize to or thank my friends. Thank you to my suitemates—Mark, Jackson, Kal, Derek, and Gerry—in particular. Thank you to Ruby, my intellectual soul mate, for venturing with me— through Adorno, Melville, and Flaubert—along our path to mystical modernism. I see this essay as a partial capstone to that journey. Thank you to Max for preventing me from thinking that “this is not the land of truth.” Thank you to Elena for humoring me during many a procrastination break outside of Butler. -

Neoconservatism Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative Hberkc Ch5 Mp 104 Rev1 Page 104 Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative Hberkc Ch5 Mp 105 Rev1 Page 105

Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_103 rev1 page 103 part iii Neoconservatism Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_104 rev1 page 104 Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_105 rev1 page 105 chapter five The Neoconservative Journey Jacob Heilbrunn The Neoconservative Conspiracy The longer the United States struggles to impose order in postwar Iraq, the harsher indictments of the George W. Bush administration’s foreign policy are becoming. “Acquiring additional burdens by engag- ing in new wars of liberation is the last thing the United States needs,” declared one Bush critic in Foreign Affairs. “The principal problem is the mistaken belief that democracy is a talisman for all the world’s ills, and that the United States has a responsibility to promote dem- ocratic government wherever in the world it is lacking.”1 Does this sound like a Democratic pundit bashing Bush for par- tisan gain? Quite the contrary. The swipe came from Dimitri Simes, president of the Nixon Center and copublisher of National Interest. Simes is not alone in calling on the administration to reclaim the party’s pre-Reagan heritage—to abandon the moralistic, Wilsonian, neoconservative dream of exporting democracy and return to a more limited and realistic foreign policy that avoids the pitfalls of Iraq. 1. Dimitri K. Simes, “America’s Imperial Dilemma,” Foreign Affairs (Novem- ber/December 2003): 97, 100. Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_106 rev1 page 106 106 jacob heilbrunn In fact, critics on the Left and Right are remarkably united in their assessment of the administration. Both believe a neoconservative cabal has hijacked the administration’s foreign policy and has now overplayed its hand. -

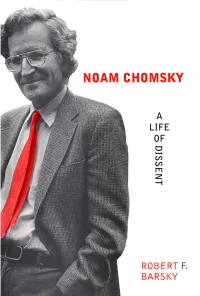

Noam Chomsky Noam Chomsky Addressing a Crowd at the University of Victoria, 1989

Noam Chomsky Noam Chomsky addressing a crowd at the University of Victoria, 1989. Noam Chomsky A Life of Dissent Robert F. Barsky ECW PRESS Copyright © ECW PRESS, 1997 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any process—electronic, mechan- ical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of the copyright owners and ECW PRESS. CANADIAN CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION DATA Barsky, Robert F. (Robert Franklin), 1961- Noam Chomsky: a life of dissent Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-55022-282-1 (bound) ISBN 1-55022-281-3 (pbk.) 1. Chomsky, Noam. 2. Linguists—United States—Biography. I. Title. P85.C47B371996 410'.92 C96-930295-9 This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Humanities and Social Sciences Federation of Canada, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, and with the assistance of grants provided by the Ontario Arts Council and The Canada Council. Distributed in Canada by General Distribution Services, 30 Lesmill Road, Don Mills, Ontario M3B 2T6. Distributed in the United States and internationally by The MIT Press. Photographs: Cover (1989), frontispiece (1989), and illustrations 18, 24, 25 (1989), © Elaine Briere; illustration 1 (1992), © Donna Coveney, is used by per- mission of Donna Coveney; illustrations 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 19, 20,21,22,23,26, © Necessary Illusions, are used by permission of Mark Achbar and Jeremy Allaire; illustrations 5, 8, 9, 10 (1995), © Robert F. -

New Atheism and the Scientistic Turn in the Atheism Movement MASSIMO PIGLIUCCI

bs_bs_banner MIDWEST STUDIES IN PHILOSOPHY Midwest Studies In Philosophy, XXXVII (2013) New Atheism and the Scientistic Turn in the Atheism Movement MASSIMO PIGLIUCCI I The so-called “New Atheism” is a relatively well-defined, very recent, still unfold- ing cultural phenomenon with import for public understanding of both science and philosophy.Arguably, the opening salvo of the New Atheists was The End of Faith by Sam Harris, published in 2004, followed in rapid succession by a number of other titles penned by Harris himself, Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennett, Victor Stenger, and Christopher Hitchens.1 After this initial burst, which was triggered (according to Harris himself) by the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, a number of other authors have been associated with the New Atheism, even though their contributions sometimes were in the form of newspapers and magazine articles or blog posts, perhaps most prominent among them evolutionary biologists and bloggers Jerry Coyne and P.Z. Myers. Still others have published and continue to publish books on atheism, some of which have had reasonable success, probably because of the interest generated by the first wave. This second wave, however, often includes authors that explicitly 1. Sam Harris, The End of Faith: Religion, Terror, and the Future of Reason (New York: W.W. Norton, 2004); Sam Harris, Letter to a Christian Nation (New York: Vintage, 2006); Richard Dawkins, The God Delusion (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2006); Daniel C. Dennett, Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon (New York: Viking Press, 2006); Victor J. Stenger, God:The Failed Hypothesis: How Science Shows That God Does Not Exist (Amherst, NY: Prometheus, 2007); Christopher Hitchens, God Is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything (New York: Twelve Books, 2007). -

By Christopher Hitchens

1 god is not great by Christopher Hitchens Contents One - Putting It Mildly 03 Two - Religion Kills 07 Three - A Short Digression on the Pig; or, Why Heaven Hates Ham 15 Four - A Note on Health, to Which Religion Can Be Hazardous 17 Five - The Metaphysical Claims of Religion Are False 24 Six - Arguments from Design 27 Seven - Revelation: The Nightmare of the "Old" Testament 35 Eight - The "New" Testament Exceeds the Evil of the "Old" One 39 Nine - The Koran Is Borrowed from Both Jewish and Christian Myths 44 Ten - The Tawdriness of the Miraculous and the Decline of Hell 49 Eleven - "The Lowly Stamp of Their Origin": Religion's Corrupt Beginnings 54 Twelve - A Coda: How Religions End 58 Thirteen - Does Religion Make People Behave Better? 60 Fourteen - There Is No "Eastern" Solution 67 Fifteen - Religion as an Original Sin 71 Sixteen - Is Religion Child Abuse? 75 Seventeen - An Objection Anticipated: The Last-Ditch "Case" Against Secularism 79 Eighteen - A Finer Tradition: The Resistance of the Rational 87 Nineteen - In Conclusion: The Need for a New Enlightenment 95 Acknowledgments 98 References 99 2 Oh, wearisome condition of humanity, Born under one law, to another bound; Vainly begot, and yet forbidden vanity, Created sick, commanded to be sound. —FULKE GREVILLE, Mustapha And do you think that unto such as you A maggot-minded, starved, fanatic crew God gave a secret, and denied it me? Well, well—what matters it? Believe that, too! —THE RUBAIYAT OF OMAR KHAYYAM (RICHARD LE GALLIENNE TRANSLATION) Peacefully they will die, peacefully they will expire in your name, and beyond the grave they will find only death. -

Environmental and Social Stress Factors

Urban Research in the Developing World: From Governance to Security Richard Stren Project on Urbanization, Population, Environment, and Security. Supported by the U.S. Agency for International Development through a cooperative agreement with the University of Michigan Population Fellows Programs Comparative Urban Studies Project Occasional Paper No. 16 WOODROW WILSON INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR SCHOLARS, 1998 1 RICHARD STREN Urban Research in the Developing World: From Governance to Security Richard Stren Director, Center for Urban and Community Studies University of Toronto Toronto, Canada Introduction: Building an Urban Research Agenda Against the backdrop of a major demographic shift from rural to urban in most parts of the world (a shift that has already been largely accomplished in Europe, North America, and much of Latin America), the research literature on urban questions has shown a number of distinct patterns over the years. One pattern is the continuing influence of international disciplinary perspectives. In spite of the fact that urban questions cut across disciplines, and that solutions to urban problems involve ideas and coalitions of interests that are usually very broad and projects that are very practical, researchers--and the research literature--tend to be specialized. Thus, an economist in Bombay is likely to choose themes and a methodological approach to her urban problems that are more similar to her economist colleagues in Santiago than to her sociological colleagues in Delhi. In spite of some tendencies toward interdisciplinary research in urban studies worldwide, the disciplines--which are organized at a global level with common standards of approach, journals, conferences, and professional behavior--are still very powerful. -

Imagination Movers: the Construction of Conservative Counter-Narratives in Reaction to Consensus Liberalism

Imagination Movers: The Construction of Conservative Counter-Narratives in Reaction to Consensus Liberalism Seth James Bartee Dissertation submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Social, Political, Ethical, and Cultural Thought Francois Debrix, Chair Matthew Gabriele Matthew Dallek James Garrison Timothy Luke February 19, 2014 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: conservatism, imagination, historicism, intellectual history counter-narrative, populism, traditionalism, paleo-conservatism Imagination Movers: The Construction of Conservative Counter-Narratives in Reaction to Consensus Liberalism Seth James Bartee ABSTRACT The purpose of this study was to explore what exactly bound post-Second World War American conservatives together. Since modern conservatism’s recent birth in the United States in the last half century or more, many historians have claimed that both anti-communism and capitalism kept conservatives working in cooperation. My contention was that the intellectual founder of postwar conservatism, Russell Kirk, made imagination, and not anti-communism or capitalism, the thrust behind that movement in his seminal work The Conservative Mind. In The Conservative Mind, published in 1953, Russell Kirk created a conservative genealogy that began with English parliamentarian Edmund Burke. Using Burke and his dislike for the modern revolutionary spirit, Kirk uncovered a supposedly conservative seed that began in late eighteenth-century England, and traced it through various interlocutors into the United States that culminated in the writings of American expatriate poet T.S. Eliot. What Kirk really did was to create a counter-narrative to the American liberal tradition that usually began with the French Revolution and revolutionary figures such as English-American revolutionary Thomas Paine. -

Faith Defense

Faith Defense “But in your hearts honor Christ the Lord as holy, always being prepared to make a defense to anyone who asks you for a reason for the hope that is in you; yet do it with gentleness and respect,” 1-Peter 3:15 Why We Need Faith-Defense On July 4, 1976, the Lord God turned my central life’s focus and commitment from “self-defense” to “faith-defense” commitment. I left the land of independence for the land of dependence upon God the Lord Jesus Christ our Savior. Since 1980, I have been serving as a missionary with Things to Come Mission, located in Indianapolis, Indiana. The arts of self-defense and faith-defense are as old as the history of the human race. In fact, faith- defense was the first art God taught the first human being. “Then the LORD God took the man and put him in the Garden of Eden, to tend and to keep it. And the LORD God commanded the man saying, ‘Of every tree of the garden you may freely eat; but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil you shall not eat, for in the day that you eat of it you shall surely die.'” (Genesis 2:15-17) God created Adam, then, placed him in the Garden of Eden and told him “to tend and keep it.” “To tend” means “to work or labor” in the garden. “To keep” means “to guard, protect, keep it safe, preserve” the garden. We understand that the garden needed someone working in it to plant and harvest, but why did it need protection? God had a powerful enemy – not as powerful as God, but still powerful. -

My Orwell Right Or Wrong

www.libertarian-alliance.org.uk orwell.pdf - From the website of the Libertarian Alliance homosexuality, Hichens says: “Only one My Orwell Right or of his inherited prejudices––the shudder generated by homosexuality––appears to Wrong have resisted the process of self-mastery” (p. 9). Here Hitchens conveys to the Why Orwell Matters, by Christopher reader two surmises which are not Hitchens. Basic Books, 2002, 211 + xii corroborated by any recorded utterance pages. A book review by David of Orwell, and which I believe to be Ramsay Steele false: that Orwell disapproved of homosexuality because it revolted him physically, and that Orwell made an At the end of his book on George Orwell, unsuccessful effort to subdue this gut Christopher Hitchens solemnly intones response. that “‘views’ do not really matter,” that Orwell harbored no unreasoning, “it matters not what you think but how visceral horror of homosexuality and he you think,” and that politics is “relatively did not strive to overcome his unimportant.” The preceding 210 pages disapproval of it. The evidence suggests tell a different story: that a person is to that, if anything, he was less inclined to be judged chiefly by his opinions and any such shuddering than most that politics is all-important. heterosexuals. His descriptions of his Why Orwell Matters is an encounters with homosexuality are advocate’s defense of Orwell as a good always cool, dispassionate, even and great man. The evidence adduced is sympathetic. His disapproval of that Orwell held the same opinions as homosexuality was rooted in his Hitchens. Hitchens does allow that convictions.