Politics and Paradigms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bangor University DOCTOR of PHILOSOPHY Reimagining

Bangor University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Reimagining Everyday Life in the GDR Post-Ostalgia in Contemporary German Films and Museums Kreibich, Stefanie Award date: 2019 Awarding institution: Bangor University Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 Reimagining Everyday Life in the GDR: Post-Ostalgia in Contemporary German Films and Museums Stefanie Kreibich Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Modern Languages Bangor University, School of Modern Languages and Cultures April 2018 Abstract In the last decade, everyday life in the GDR has undergone a mnemonic reappraisal following the Fortschreibung der Gedenkstättenkonzeption des Bundes in 2008. No longer a source of unreflective nostalgia for reactionaries, it is now being represented as a more nuanced entity that reflects the complexities of socialist society. The black and white narratives that shaped cultural memory of the GDR during the first fifteen years after the Wende have largely been replaced by more complicated tones of grey. -

Überseehafen Rostock: East Germany’S Window to the World Under Stasi Watch, 1961-1989

Tomasz Blusiewicz Überseehafen Rostock: East Germany’s Window to the World under Stasi Watch, 1961-1989 Draft: Please do not cite Dear colleagues, Thank you for your interest in my dissertation chapter. Please see my dissertation outline to get a sense of how it is going to fit within the larger project, which also includes Poland and the Soviet Union, if you're curious. This is of course early work in progress. I apologize in advance for the chapter's messy character, sloppy editing, typos, errors, provisional footnotes, etc,. Still, I hope I've managed to reanimate my prose to an edible condition. I am looking forward to hearing your thoughts. Tomasz I. Introduction Alexander Schalck-Golodkowski, a Stasi Oberst in besonderen Einsatz , a colonel in special capacity, passed away on June 21, 2015. He was 83 years old. Schalck -- as he was usually called by his subordinates -- spent most of the last quarter-century in an insulated Bavarian mountain retreat, his career being all over three weeks after the fall of the Wall. But his death did not pass unnoticed. All major German evening TV news services marked his death, most with a few minutes of extended commentary. The most popular one, Tagesschau , painted a picture of his life in colors appropriately dark for one of the most influential and enigmatic figures of the Honecker regime. True, Mielke or Honecker usually had the last word, yet Schalck's aura of power appears unparalleled precisely because the strings he pulled remained almost always behind the scenes. "One never saw his face at the time. -

Introduction After Totalitarianism – Stalinism and Nazism Compared

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89796-9 - Beyond Totalitarianism: Stalinism and Nazism Compared Michael Geyer and Sheila Fitzpatrick Excerpt More information 1 Introduction After Totalitarianism – Stalinism and Nazism Compared Michael Geyer with assistance from Sheila Fitzpatrick The idea of comparing Nazi Germany with the Soviet Union under Stalin is not a novel one. Notwithstanding some impressive efforts of late, however, the endeavor has achieved only limited success.1 Where comparisons have been made, the two histories seem to pass each other like trains in the night. That is, while there is some sense that they cross paths and, hence, share a time and place – if, indeed, it is not argued that they mimic each other in a deleterious war2 – little else seems to fit. And this is quite apart from those approaches which, on principle, deny any similarity because they consider Nazism and Stalinism to be at opposite ends of the political spectrum. Yet, despite the very real difficulties inherent in comparing the two regimes and an irreducible political resistance against such comparison, attempts to establish their commonalities have never ceased – not least as a result of the inclination to place both regimes in opposition to Western, “liberal” traditions. More often than not, comparison of Stalinism and Nazism worked by way of implicating a third party – the United States.3 Whatever the differences between them, they appeared small in comparison with the chasm that separated them from liberal-constitutional states and free societies. Since a three-way comparison 1 Alan Bullock, Hitler and Stalin: Parallel Lives (London: HarperCollins, 1991); Ian Kershaw and Moshe Lewin, eds., Stalinism and Nazism: Dictatorships in Comparison (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977); Henry Rousso, ed., Stalinisme et nazisme: Histoire et memoire´ comparees´ (Paris: Editions´ Complexe, 1999); English translation by Lucy Golvan et al., Stalinism and Nazism (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004); Richard J. -

DISCUSSION the Goldhagen Controversy

DISCUSSION The Goldhagen Controversy: Agonizing Problems, Scholarly Failure and the Downloaded from Political Dimension’ Hans-Ulrich Wehler (BieZefeZd) http://gh.oxfordjournals.org/ When a contentious book with a provoca1.ive message has aroused lively, not to say passionate, controversy, it is desirable that any new contribution to the debate should strive to provide as sober and clear a cost-benefit analysis as possible. It is best, moreover, to attend first to the book’s merits and achieve- ments, before giving an equal airing to its faults and limitations. In the case of Daniel Goldhagen’s Hiller’s Willing Executioners such a procedure is parti- cularly advisable, since the response in the American and German media to at Serials Department on February 18, 2015 this six-hundred-page study of ‘ordinary Germans and the Holocaust’ has not only been rather speedier than that of the academic world-though scholarly authorities have also, uncharacteristically, been quick off the mark-but has impaired the debate by promptly giving respectability to a number of stereo- types and misconceptions. The enthusiastic welcome that the book has received from journalists and opinion-formers in America is a problem in its own right, and we shall return to it later. But here in Germany there is no cause for complacency either, since the reaction in the public media has been far from satisfactory. With dismaying rapidity, and with a spectacular self-confidence that has frequently masked an ignorance of the facts, a counter-consensus has emerged. The book, we are repeatedly told, contains no new empirical data, since everything of significance on the subject has long been known; nor does it raise any stimulating new questions. -

Conservative Parties and the Birth of Democracy

Conservative Parties and the Birth of Democracy How do democracies form and what makes them die? Daniel Ziblatt revisits this timely and classic question in a wide-ranging historical narrative that traces the evolution of modern political democracy in Europe from its modest beginnings in 1830s Britain to Adolf Hitler’s 1933 seizure of power in Weimar Germany. Based on rich historical and quantitative evidence, the book offers a major reinterpretation of European history and the question of how stable political democracy is achieved. The barriers to inclusive political rule, Ziblatt finds, were not inevitably overcome by unstoppable tides of socioeconomic change, a simple triumph of a growing middle class, or even by working class collective action. Instead, political democracy’s fate surprisingly hinged on how conservative political parties – the historical defenders of power, wealth, and privilege – recast themselves and coped with the rise of their own radical right. With striking modern parallels, the book has vital implications for today’s new and old democracies under siege. Daniel Ziblatt is Professor of Government at Harvard University where he is also a resident fellow of the Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies. He is also currently Fernand Braudel Senior Fellow at the European University Institute. His first book, Structuring the State: The Formation of Italy and Germany and the Puzzle of Federalism (2006) received several prizes from the American Political Science Association. He has written extensively on the emergence of democracy in European political history, publishing in journals such as American Political Science Review, Journal of Economic History, and World Politics. -

Hitler, Britain and the Hoßbach Memorandum

Jonathan Wright and Paul Stafford* Hitler, Britain and the Hoßbach Memorandum The Hoßbach Memorandum is the most famous and most controversial document in the history of the Third Reich. Yet there is no critical edition of it — a telling example of the degree to which historians of the twentieth century are swamped by their sources. Every line of the document deserves close study. It contains one of the classic statements of Hitler's racial philosophy and of the policy of the conquest of living space to solve Germany's economic problems. On this level it is comparable to passages in Mein Kampf and the Memorandum on the tasks of the Four Year Plan. But the Hoßbach Memorandum also offers an insight into another dimension of Hitler's thought: the first recorded detailed argument about when and how the conquest of liv- ing space was to begin. The essence of this argument is that Germany had limited time at its disposal because its relative strength compared to its opponents would decline after 1943—45 and that was therefore the final date for action. Hitler appeared confi- dent about the international situation. The weakness of the British Empire, which he elaborated in some detail, and the domestic divisions of the French Republic, Russian fear of Japan and Polish fear of Russia, the favourable attitude of Italy so long as the Duce was alive, all he declared offered Germany an opportunity to destroy Czechoslo- vakia and simultaneously to absorb Austria with little risk of intervention by other powers. Hitler also discussed two possible developments which would enable Germany to act before 1943—45: a domestic crisis in France which made it unable to go to war, or France becoming involved in war with another power which he saw as an immediate possibility for 1938 arising out of the Spanish civil war. -

Hitler's War Aims

Hitler’s War Aims Gerhard Hirschfeld Between 1939 and 1945, the German Reich dominated large parts of Europe. It has been estimated that by the end of 1941 approximately 180 million non-Germans lived under some form of German occupation. Inevitably, the experience and memory of the war for most Europeans is therefore linked less with military action and events than with Nazi (i.e. National Socialist) rule and the manifold expressions it took: insecurity and unlawfulness, constraints and compulsion, increasing difficult living conditions, coercive measures and arbitrary acts of force, which ultimately could threaten the very existence of peoples. Moreover, for those millions of human beings whose right to existence had been denied for political, social, or for – what the Nazis would term – ‘racial motives’ altogether, the implications and consequences of German conquest and occupation of Europe became even more oppressive and hounding.1 German rule in Europe during the Second World War involved a great variety of policies in all countries under more or less permanent occupation, determined by political, strategically, economical and ideological factors. The apparent ‘lack of administrative unity’ (Hans Umbreit) in German occupied Europe was often lamented but never seriously re-considered.2 The peculiar structure of the German ‘leader-state’ (Fuehrerstaat) and Hitler's obvious indifference in all matters of administration, above, his well known indecisiveness in internal matters of power, made all necessary changes, except those dictated by the war itself, largely obsolete. While in Eastern Europe the central purpose of Germany's conquest was to provide the master race with the required ‘living space’ (Lebensraum) for settlement as well as human and economic resources for total exploitation, the techniques for political rule and economic control appeared less brutal in Western Europe, largely in accordance with Hitler’s racial and ideological views. -

Schriftelijk Interview Met Gerhard Hirschfeld

Interview met Gerhard Hirschfeld Buys Ballot, IJsbrand Citation Buys Ballot, I. J. (2005). Interview met Gerhard Hirschfeld. Leidschrift : Duitsland En De Eerste Wereldoorlog, 20(December), 121-130. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/73226 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) License: Leiden University Non-exclusive license Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/73226 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). Schriftelijk interview met Gerhard Hirschfeld IJsbrand Buys Ballot First, can you tell us something about yourself, your work and your interests in history? What made you become fascinated by the First World War? I graduated in 1974 from the University of Cologne (having studied history, political science and German language and literature) and then taught for a couple of years at University College Dublin and at the Heinrich Heine- Universität of Düsseldorf (as assistant to Gerhard Hirschfeld Wolfgang J. Mommsen), where I received my doctorate in 1981. For eleven years I worked as a Research Fellow at the German Historical Institute in London before I became director of the Bibliothek für Zeitgeschichte (Library of Contemporary History) in Stuttgart, an international research library with archival collections specializing in the period from 1914 to the present. I was a NIAS-Fellow at Wassenaar in 1996/1997 and in the same year I was appointed Professor of Modern History at the University of Stuttgart. There are basically two reasons why I became interested in the history of the First World War. First I began my professional work as a historian of the Second World War – my dissertation dealt with the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands and the question of accommodation and collaboration exercised by large parts of the Dutch population – and I kept asking myself if the history of the German occupation would have turned out differently if the Netherlands had not been spared the experience of a previous total war. -

Television and the Cold War in the German Democratic Republic

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE Revised Pages Envisioning Socialism Revised Pages Revised Pages Envisioning Socialism Television and the Cold War in the German Democratic Republic Heather L. Gumbert The University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Revised Pages Copyright © by Heather L. Gumbert 2014 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (be- yond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2017 2016 2015 2014 5 4 3 2 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978– 0- 472– 11919– 6 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978– 0- 472– 12002– 4 (e- book) Revised Pages For my parents Revised Pages Revised Pages Contents Acknowledgments ix Abbreviations xi Introduction 1 1 Cold War Signals: Television Technology in the GDR 14 2 Inventing Television Programming in the GDR 36 3 The Revolution Wasn’t Televised: Political Discipline Confronts Live Television in 1956 60 4 Mediating the Berlin Wall: Television in August 1961 81 5 Coercion and Consent in Television Broadcasting: The Consequences of August 1961 105 6 Reaching Consensus on Television 135 Conclusion 158 Notes 165 Bibliography 217 Index 231 Revised Pages Revised Pages Acknowledgments This work is the product of more years than I would like to admit. -

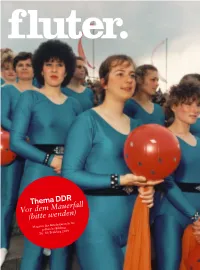

Thema DDR Vor Dem Mauerfall (Bitte Wenden)

Thema DDR Vor dem Mauerfall (bitte wenden) Magazin der Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung Nr. 30 / Frühling 2009 Was nicht in Alle bpb-Produkte unter www.bpb.de EDITORIAL INHALT diesem Heft steht, steht woanders Die DDR war einmal. »Sich dumm zu stellen, war eine Form von Und zwar hier: Sachbücher, Für viele ist es ein Land, das sie nur aus Erzählungen Opposition« . Seite 4 kennen. Aus diesem Block historischen Materials, Zuckerbrot und Peitsche: Der Historiker Stefan Romane, Broschüren, Filme der durch die Entfernung oft etwas Märchenhaf- Wolle über den Alltag in der DDR und den sprung- & Links zum Thema tes bekommt, hat fluter einige Geschichten heraus- haften Umgang der Regierung mit dem Volk gegriffen. Bei aller Komplexität – es gibt ein paar einfache Wahrheiten: Ein Staat, der seine Bürger Ein Stück Karibik . Seite 10 einsperrt und ermordet, wenn sie fliehen wollen, Es wäre ja auch zu schön gewesen: Die Geschichte ist kein guter Staat. Ein politisches System, das ei- von einer DDR-Insel brachte Wind in die Köpfe ner kleinen Gruppe alter Männer unkontrollierte Macht über alles gibt, ist eine Diktatur. Auch wenn Lost in Music . Seite 11 Stefan Wolle: Werner Bräunig: ONLINE: Die heile Welt der Diktatur Rummelplatz sie sich den Namen »Demokratische Republik« Völlig aus dem Takt: Nichts haben die Machthaber Stefan Wolle gelingt es, die widersprüchlichen Bilder Nach dem Vorabdruck einiger Kapitel fiel Bräunig, Auf der Seite »Deine Geschichte«können Jugend- gibt. Diktaturen sind im besten Fall absurd und in so gefürchtet wie Jugendbewegungen. Rock, Beat einer unter gegangenen Welt zusammenzufügen. der schreibende Bergmann, bei der SED in Ungnade. -

Was World War II the Result of Hitler's Master Plan?

ISSUE 18 Was World War II the Result of Hitler's Master Plan? Yl!S: Andreas Hillgruber, from Germany and the Two World Wars, trans. WUliam C. Kirby (Harvard University Press, 1981) NO: Ian Kershaw, from The Nazi DictatoTShip: Problems and Per spectives ofInterpretation, 3Id ed. (Edward Arnold, 1993) ISSUE SUMMARY YES: German scholar and history professor Andreas Hlllgruber states that Hitler systematically pursued his foreign policy goals once he came to power In Germany and that World War II was the Inevitable result. NO: Ian Kershaw, a professor ofhistory at the University of Sheffield, argues that Hitler was responsible for the execution of German for eign policy that Jed to World War JI but was not free from forces both within and outside Germany that Influenced his decisions. Adolf Hitler and World War II have become inseparable In the minds of most people; any discussion of one ultimately leads to the other- Due to the diabo1-. ical nature of Hitler's actions and the resulting horrors, historical analyses of the war were slow to surface after the war; World War II was simply viewed as Hitler's war, and all responsibility for It began and ended with him. Th.is all changed In 1961 with the publication of A.]. P. Tuylor's The Ori gins of the Second World War (Atheneum, 1985). Taylor extended the scope of World War II beyond Hitler and found British and French actions culpable. Fur thermore, he stated that Hitler was more of an opportunist than an idealogue and that war was the result of misconceptions and blunders on both sides. -

Totalitarianism 1 Totalitarianism

Totalitarianism 1 Totalitarianism Totalitarianism (or totalitarian rule) is a political system where the state holds total authority over the society and seeks to control all aspects of public and private life wherever necessary.[1] The concept of totalitarianism was first developed in a positive sense in the 1920's by the Italian fascists. The concept became prominent in Western anti-communist political discourse during the Cold War era in order to highlight perceived similarities between Nazi Germany and other fascist regimes on the one hand, and Soviet communism on the other.[2][3][4][5][6] Aside from fascist and Stalinist movements, there have been other movements that are totalitarian. The leader of the historic Spanish reactionary conservative movement called the Spanish Confederation of the Autonomous Right declared his intention to "give Spain a true unity, a new spirit, a totalitarian polity..." and went on to say "Democracy is not an end but a means to the conquest of the new state. Moloch of Totalitarianism – memorial of victims of repressions exercised by totalitarian regimes, When the time comes, either parliament submits or we will eliminate at Levashovo, Saint Petersburg. it."[7] Etymology The notion of "totalitarianism" a "total" political power by state was formulated in 1923 by Giovanni Amendola who described Italian Fascism as a system fundamentally different from conventional dictatorships.[8] The term was later assigned a positive meaning in the writings of Giovanni Gentile, Italy’s most prominent philosopher and leading theorist of fascism. He used the term “totalitario” to refer to the structure and goals of the new state.