The Beige Conundrum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yagenich L.V., Kirillova I.I., Siritsa Ye.A. Latin and Main Principals Of

Yagenich L.V., Kirillova I.I., Siritsa Ye.A. Latin and main principals of anatomical, pharmaceutical and clinical terminology (Student's book) Simferopol, 2017 Contents No. Topics Page 1. UNIT I. Latin language history. Phonetics. Alphabet. Vowels and consonants classification. Diphthongs. Digraphs. Letter combinations. 4-13 Syllable shortness and longitude. Stress rules. 2. UNIT II. Grammatical noun categories, declension characteristics, noun 14-25 dictionary forms, determination of the noun stems, nominative and genitive cases and their significance in terms formation. I-st noun declension. 3. UNIT III. Adjectives and its grammatical categories. Classes of adjectives. Adjective entries in dictionaries. Adjectives of the I-st group. Gender 26-36 endings, stem-determining. 4. UNIT IV. Adjectives of the 2-nd group. Morphological characteristics of two- and multi-word anatomical terms. Syntax of two- and multi-word 37-49 anatomical terms. Nouns of the 2nd declension 5. UNIT V. General characteristic of the nouns of the 3rd declension. Parisyllabic and imparisyllabic nouns. Types of stems of the nouns of the 50-58 3rd declension and their peculiarities. 3rd declension nouns in combination with agreed and non-agreed attributes 6. UNIT VI. Peculiarities of 3rd declension nouns of masculine, feminine and neuter genders. Muscle names referring to their functions. Exceptions to the 59-71 gender rule of 3rd declension nouns for all three genders 7. UNIT VII. 1st, 2nd and 3rd declension nouns in combination with II class adjectives. Present Participle and its declension. Anatomical terms 72-81 consisting of nouns and participles 8. UNIT VIII. Nouns of the 4th and 5th declensions and their combination with 82-89 adjectives 9. -

Textile Society of America Newsletter 28:1 — Spring 2016 Textile Society of America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Newsletters Textile Society of America Spring 2016 Textile Society of America Newsletter 28:1 — Spring 2016 Textile Society of America Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews Part of the Art and Design Commons Textile Society of America, "Textile Society of America Newsletter 28:1 — Spring 2016" (2016). Textile Society of America Newsletters. 73. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews/73 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Newsletters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. VOLUME 28. NUMBER 1. SPRING, 2016 TSA Board Member and Newsletter Editor Wendy Weiss behind the scenes at the UCB Museum of Anthropology in Vancouver, durring the TSA Board meeting in March, 2016 Spring 2016 1 Newsletter Team BOARD OF DIRECTORS Roxane Shaughnessy Editor-in-Chief: Wendy Weiss (TSA Board Member/Director of External Relations) President Designer and Editor: Tali Weinberg (Executive Director) [email protected] Member News Editor: Caroline Charuk (Membership & Communications Coordinator) International Report: Dominique Cardon (International Advisor to the Board) Vita Plume Vice President/President Elect Editorial Assistance: Roxane Shaughnessy (TSA President) [email protected] Elena Phipps Our Mission Past President [email protected] The Textile Society of America is a 501(c)3 nonprofit that provides an international forum for the exchange and dissemination of textile knowledge from artistic, cultural, economic, historic, Maleyne Syracuse political, social, and technical perspectives. -

Tyrian Purple: Its Evolution and Reinterpretation As Social Status Symbol During the Roman Empire in the West

Tyrian Purple: Its Evolution and Reinterpretation as Social Status Symbol during the Roman Empire in the West Master’s Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Graduate Program in Ancient Greek and Roman Studies Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow and Andrew J. Koh, Advisors In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Ancient Greek and Roman Studies by Mary Pons May 2016 Acknowledgments This paper truly would not have come to be without the inspiration provided by Professor Andrew Koh’s Art and Chemistry class. The curriculum for that class opened my mind to a new paradigmatic shift in my thinking, encouraging me to embrace the possibility of reinterpreting the archaeological record and the stories it contains through the lens of quantifiable scientific data. I know that I would never have had the courage to finish this project if it were not for the support of my advisor Professor Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow, who never rejected my ideas as outlandish and stayed with me as I wrote and rewrote draft after draft to meet her high standards of editorial excellence. I also owe a debt of gratitude to my parents, Gary and Debbie Pons, who provided the emotional support I needed to get through my bouts of insecurity. When everything I seemed to put on the page never seemed good enough or clear enough to explain my thought process, they often reminded me to relax, sleep, walk away from it for a while, and try again another day. -

Miming Modernity: Representations of Pierrot in Fin-De-Siècle France

Southern Methodist University SMU Scholar Art History Theses and Dissertations Art History Spring 5-15-2021 Miming Modernity: Representations of Pierrot in Fin-de-Siècle France Ana Norman [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/arts_arthistory_etds Part of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, and the Modern Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Norman, Ana, "Miming Modernity: Representations of Pierrot in Fin-de-Siècle France" (2021). Art History Theses and Dissertations. 7. https://scholar.smu.edu/arts_arthistory_etds/7 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art History Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. MIMING MODERNITY: REPRESENTATIONS OF PIERROT IN FIN-DE-SIÈCLE FRANCE Approved by: _______________________________ Dr. Amy Freund Associate Professor of Art History _______________________________ Dr. Elizabeth Eager Assistant Professor of Art History _______________________________ Dr. Randall Griffin Distinguished Professor of Art History !"Doc ID: ec9532a69b51b36bccf406d911c8bbe8b5ed34ce MIMING MODERNITY: REPRESENTATIONS OF PIERROT IN FIN-DE-SIÈCLE FRANCE A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty of Meadows School of the Arts Southern Methodist University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Art History by Ana Norman B.A., Art History, University of Dallas May 15, 2021 Norman, Ana B.A., Art History, University of Dallas Miming Modernity: Representations of Pierrot in Fin-de-Si cle France Advisor: Dr. Amy Freund Master of Art History conferred May 15, 2021 Thesis completed May 3, 2021 This thesis examines the commedia dell’arte character Pierrot through the lens of gender performance in order to decipher the ways in which he complicates and expands understandings of gender and the normative model of sexuality in fin de siècle France. -

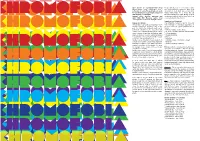

People with the Fear of Colors Tend to Suffer from Many Debilitating

CHROMOFOBIA (also known as chromatophobia) (from People with the fear of colors tend to suffer Greek chroma, “color” and phobos, “fear”) from many debilitating symptoms. Often, they is the fear of colors.The worst place to be in are unable to hold down jobs or even have CHROMOFOBIA for chromophobes is Las Vegas because of steady relationships. As a result, life can CHROMOFOBIA their brightly colored lights. become miserable for them. Going outdoors Famous actor, director, musician and can become a difficult task for them, for the fear writer Billy Bob Thornton suffers from of encountering the hated colors. chromophobia, or the fear of bright colours. Symptoms and treatment Causes and effects The symptoms of effects of fear of color vary This phobia is caused by post traumatic stress from individual to individual depending on CHROMOFOBIA disorder experiences involving colors in the the level of the fear. Typical symptoms are as CHROMOFOBIA past. An event in the childhood might lead to follows: permanent emotional scars associated with * Extreme anxiety or panic attack certain colors or shades which the phobic simply * Shortness of breath- rapid and shallow breaths cannot outgrow. Events like child abuse, rape, * Profuse sweating death, accidents or violence, could all be related * Irregular heartbeat to a particular color causing the phobic to panic * Nausea or become anxious in its presence. * Dry mouth CHROMOFOBIA Another cause of the fear of colors stems from * Inability to speak or formulate coherent cultural roots. Certain cultures have significant sentences CHROMOFOBIA meanings for specific colors which can have a * Shaking, shivering, trembling CHROMOFOBIA negative connotation for the phobic. -

Chromophobia, Or Chromatophobia, Is an Irrational Fear of Certain Colors

Chromophobia, Or Chromatophobia, Is An Irrational Fear Of Certain Colors National Color Day focuses on the affect color has on each of us. The observance takes place each year on October 22. Color is powerful. It can affect a mood, draw attention, even cause alarm. Different colors are perceived to mean different things. The following is one rendition of the perceived meaning of the various colors in the United States. Red: Excitement – Love – Strength Yellow: Competence – Happiness Green: Good Taste – Envy – Relaxation Blue: Corporate – High Quality Pink: Sophistication – Sincerity Violet/Purple: Authority – Power Brown: Ruggedness Black: Grief – Fear White: Happiness – Purity. You’re more likely to forget something when it’s in black and white. Psychologists have found a number of connections between color and memory. As it turns out, people have more trouble remembering facts presented in black and white than they do facts presented in color. There’s a reason you never see yellow in an airplane. A number of studies have shown that the color yellow can cause dizziness and nausea. For this reason, it’s often used sparingly (or very strategically) by those in advertising, and is almost never used in the interiors of various forms of transportation — most notably, airplanes. It’s possible to be afraid of certain colors. Chromophobia, or Chromatophobia, refers to an irrational fear of or aversion to certain colors. Blue is the world’s favorite color. Studies done around the world reveal that a whopping 40% of people consider blue to be their favorite color. Second place goes to purple, though that received only 14%, and last place goes to black. -

Der Blaue Reiter, Walter Benjamin and the Emancipation of Color

Chromophilia: Der Blaue Reiter, Walter Benjamin and the Emancipation of Color Dr. Martin Jay Sidney Hellman Ehrman Professor of History at the University of California, Berkeley Prepared for the 2011 Yale University Forum on Art, War and Science in the 20th Century Hosted by The Jeffrey Rubinoff Sculpture Park May 19-23rd 2011 on Hornby Island, British Columbia, Canada “Indelible from the resistance to the fungible world of barter is the resistance of the eye that does not want the colors of the world to fade.” Theodor W. Adorno1 In 2003, the Wilhelm Hack Museum in the city of Ludwigshafen am Rhein mounted an exhibition entitled “Der Blaue Reiter: Die Befreiung der Farbe.”2 In what follows, I want to focus on the provocative subtitle of that show and ask the question, what did the “emancipation of color” mean for the Blaue Reiter, in particular for its most prominent figure, Wassily Kandinsky? The other artists associated with the movement, such as Robert Delauney, Franz Marc, August Macke, Alexander Jawlensky and Paul Klee, were also remarkable chromatic innovators, but Kandinsky was the most articulate spokesman of their more or less common position.3 The language of “emancipation” is , in fact, one he explicitly adopted.4 To help us clarify the stakes of his argument, I will also be examining the fragmentary, posthumously published thoughts on color by a German critic who was himself fascinated by the Blaue Reiter, Walter Benjamin, which have recently been subjected to sustained analysis by Howard Caygill and Heinz Brüggemann.5 In any history of early 20th-century visual modernism, the experiments in color performed by avant-garde communities of artists, such as the Nabis and Fauves in France and Die Brücke in Germany, are routinely foregrounded. -

Testing and Evaluation in the Biological Sciences

REPORT OF THE PANEL ON EVALUATION AND TESTING NOVEMBER 1967/CUEBS Publication 20 TESTING AND EVALUATION IN THE BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES COMMISSION ON UNDERGRADUATE EDUCATION IN THE BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES This book is a wonderful resource but had only a limited distribution back around 1967. Thanks to GWU for permission to put it in digital form so that it can be shared widely. It is still under copyright, so please read the permission letter. Biology has changed quite a bit since 1967, so many of the example questions are dated and this book doesn’t serve as a simple question bank. Yet the questions can be very useful as exemplars of questions pointed at different topics and at different cognitive levels. Since you have the digital version, it is fairly easy to copy/paste them and then update/modify as you find appropriate and useful. While I did a lot of proofreading, I’m sure I’ve missed many details, so the scanned pages in jpg format are also available. Feel free to check them if anything puzzling is found. To me, the question bank emphasizes the value of the earlier discussion in the book about assessment and evaluation methods. While most of the items given are multiple choice questions, there is also presentation and discussion about essay and matching questions. Each question, of all types, has an associated cognitive level (using Bloom’s Taxonomy). This significantly assists the instructor in assessing the progress of the students, and there is also discussion of evaluating the validity of the questions. For courses in other areas than Biology, this book can also be valuable. -

REVIEW: Two Books That Describe Pigments and Dyes, in a Different and Complementary Way

REVIEW: Two books that describe pigments and dyes, in a different and complementary way. Renata Pompas in textile dyeing. (Including numerous examples of over- dyes, or mixing of dyeing colors, to obtain the desired gradation, which debunk the myth of only-one dye substance used at a time). The sections Whites and Blacks, by Simona Rinaldi, is divided in four sub-chapters. 1. From prehistoric times to the Middle Ages, the whites made from calcium carbonate. 2. Rise and fall of lead white, from the Classical Age to the XIX century. 3. The alternatives to lead white, from 1750 to today. 4. The black pigments in the history of painting. Among the about thirty whites taken into consideration - from the Medieval ones, obtained from the shell of oysters and eggs, or marble, bones, etc..., to those of the XIX century – we can also find their presence in some very famous paintings. Of the black colors analysed it is described theirs processing technique starting from the prehistoric black carbon products. Reds, by Giuliana Quartullo, is divided into three sub-chapters. 1. The origin, manufacture and use of the red colour, from its appearance in history, to the first half of the XVI century. 2. The red color processing technique in the 1550- La fabbrica dei Colori, pigmenti e coloranti nella 1700 period. pittura e nella tintoria. (The factory of colors, pigments 3. The red colour synthesized in the laboratory and and dyes in painting and dyeing). Il Bagatto, Roma, 1986. in the painter's palettes, during the industrial Age. (pages 578) The various -

Would Colour by Any Other Name Shine As Bright? in the Light of David Batchelor’S Books on Colour: “Chromophobia” (2000), and “The Luminous and the Grey” (2014)

Would Colour by any other Name Shine as Bright? In the light of David Batchelor’s books on colour: “Chromophobia” (2000), and “The Luminous and the Grey” (2014) “It is, I believe, no exaggeration to say that, in the West, since Antiquity, colour has been systematically marginalized, reviled, diminished and degraded.”i So begins David Batchelor’s monumental reboot of how we think, write and experience colour today. As Batchelor puts it, “This loathing of colour, this fear of corruption through colour, needs a name: chromophobia.”ii Chromophobia first published in 2000, since republished in eight languages, has given the word global idiomatic status. It has acquired general usage in the artworld as well as spilling over into online dictionaries where it carries a sense of medical gravitas, suggesting a new type of psychological condition, the fear of colour, akin to other phobias such as the fear of crowds or heights. Batchelor diagnoses original symptoms of an apartheid of colour in the ancient Greeks who were the first to make a loaded differentiation between colour and its other. Aristotle had argued against colour saying that the “repository of thought in art is line, the rest is ornament.” iii Ever since colour has been understood as superficial, an ephemeral occurrence on the surface of things, whereas linearity and subdued colour is deemed permanent, structural and meaningful. Chromophobia came as a surprise to artists, cultural theorists and scientists since it spoke so stridently without aligning itself to any particular school of thought. It was decidedly non-academic and non-specialist whilst resting on a profound knowledge of the relevant scientific and aesthetic positions. -

Late Antique Aesthetics, Chromophobia, and the Red Monastery, Sohag, Egypt1

9183-06_ECA_3(2006)_01 26-10-2006 09:46 Page 1 ECA 3 (2006), p. 1-24; doi: 00.0000 / ECA.0.0.0000000 Late Antique Aesthetics, Chromophobia, and the Red Monastery, Sohag, Egypt1 Elizabeth S. BOLMAN Late antique monastics carefully structured their way of life, and in so doing generated considerable Stephen Zwirn, and I thank them for their generosity. I am material evidence, particularly in Egypt, due to the also very grateful to Dumbarton Oaks, Temple University, and the J. William Fulbright Commission for their support. excellent conditions for preservation there. They left All conservation and scholarly work on this project between varied physical traces behind, ranging from graffiti December 2002 and April 2006 has been funded by the scratched onto the walls of pagan tombs, to expertly United States Agency for International Development, bound and illuminated texts, to monumental, pur- through the Egyptian Antiquities Project of the American Research Center in Egypt, under USAID Grant No. 263- pose-built churches. Those in pursuit of the bios G-00-93-00089-00 (formerly 263-0000-G-00-3089-00). angelikos, or angelic life, chose both to adapt preex- Copyright for all Red Monastery research, photography, isting spaces for their struggles, and to build com- studies and documentation carried out during this period pletely new ones2. They embellished some of these belongs to the American Research Center in Egypt. For their support and collaboration, we thank Zahi Hawass, environments solely with roughly marked out Abdallah Kamel, Magdi al-Ghandour, Abdallah Attar, and crosses. Others, they ornamented elaborately, par- Mohammed abdel Rahim. -

ROBERT RYMAN Born 1930 in Nashville, Tennessee

This document was updated August 20, 2021. For reference only and not for purposes of publication. For more information, please contact the gallery. ROBERT RYMAN Born 1930 in Nashville, Tennessee. Died 2019 in New York. EDUCATION 1949–1950 Tennessee Polytechnic Institute, Cookeville, Tennessee SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 Robert Ryman: The First Twenty-five Years of Prints, Krakow Witkin Gallery, Boston 2018 Robert Ryman: Drawings, The Pace Gallery, New York [catalogue] 2015 Robert Ryman, Dia: Chelsea, New York [itinerary: Museo Jumex, Mexico City] [catalogue] Sylvia Plimack Mangold and Robert Ryman, Barbara Krakow Gallery, Boston [two-person exhibition] 2014 Sylvia Plimack Mangold and Robert Ryman, Barbara Krakow Gallery, Boston [two-person exhibition] White Magic: Robert Ryman / Rudolf Staffel, David Nolan, New York [two-person exhibition] 2013 Robert Ryman: Recent Paintings, The Pace Gallery, New York [catalogue] 2012 Robert Ryman: Untitled, A Painting in Four Parts, 1963–1964, Gagosian Gallery, New York 2010 Robert Ryman: Large-small, thick-thin, light reflecting, light absorbing, PaceWildenstein, New York Robert Ryman: Variations & Improvisations, Phillips Collection, Washington, DC [catalogue] 2009 Robert Ryman, Yvon Lambert, New York 2008 Advancing the Experience: Robert Ryman, Hallen für neue Kunst, Schaffhausen, Switzerland, [long-term installation 2008-2014] [catalogue] Robert Ryman, Metropol Kunstraum, Munich [catalogue] 2007 Contemporary Conversations: Robert Ryman, 1976, The Menil Collection, Houston [brochure] Robert Ryman: No