A Review of English Language Education of Jaffna Tamils

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northern Sri Lanka Jane Derges University College London Phd In

Northern Sri Lanka Jane Derges University College London PhD in Social Anthropology UMI Number: U591568 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U591568 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Fig. 1. Aathumkkaavadi DECLARATION I, Jane Derges, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources I confirm that this has been indicated the thesis. ABSTRACT Following twenty-five years of civil war between the Sri Lankan government troops and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), a ceasefire was called in February 2002. This truce is now on the point of collapse, due to a break down in talks over the post-war administration of the northern and eastern provinces. These instabilities have lead to conflicts within the insurgent ranks as well as political and religious factions in the south. This thesis centres on how the anguish of war and its unresolved aftermath is being communicated among Tamils living in the northern reaches of Sri Lanka. -

A Test of Character for Jaffna Rivals for Sissies Was Perturbed Over a Comment St

Thursday 25th February, 2010 15 93rd Battle of the Golds Letter Shopping is A test of character for Jaffna rivals for Sissies was perturbed over a comment St. Patrick’s College Jaffna College made by Mr. Trevor Chesterfield in Ihis regular column in your esteemed newspaper on 22.02.2010. Writing about terrorism and its effect on sports he retraces the history particularly cricket, in the recent past. Then he directly refers to events that led to the boycott of World Cup match- es in Sri Lanka by Australia and West Indies. This is what he wrote: “Now Shane Warne is thinking about his options. He did the same in 1996 during the World Cup when both Australia and West Indies declined to Seated from left: A. M. Monoj, M. D. Sajeenthiran, S. Sahayaraj (PoG), P. Seated from left: M. Thileepan (Asst. Coach), S. Komalatharan, S. Niroshan, S. play their games in Colombo after the Navatheepan (Captain), Rev. Fr. Gero Selvanayaham (Rector), S. Milando Jenifer (V. Seeralan (V. Capt), B. L. Mohanakumar (Physical Director), N. A. Wimalendran truck bomb at the Central Bank. Capt), P. Jeyakumar (MiC), A. S. Nishanthan (Coach), B. Michael Robert, M. V. (Principal), P. Srikugan (Captain), J. Nigethan, B. Prasad, R. Kugan (Coach). Typically,politicians opened their jaws Hamilton. Standing from left: Marino Sanjay, G. Tishanth Tuder, J. Livington, V. Standing from left: S. Vishnujan, P. Sobinathsuvan, R. Bentilkaran, K. Trasopanan, and one crassly suggested how in ref- Kuhabala, A. M. Nobert, G. Morison, Erik Prathap, V. Jehan Regilus, R. Ajith Darwin, T. Priyalakshan, N. Bengamin Nirushan, S. -

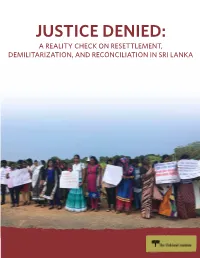

Justice Denied: a Reality Check on Resettlement, Demilitarization, And

JUSTICE DENIED: A REALITY CHECK ON RESETTLEMENT, DEMILITARIZATION, AND RECONCILIATION IN SRI LANKA JUSTICE DENIED: A REALITY CHECK ON RESETTLEMENT, DEMILITARIZATION, AND RECONCILIATION IN SRI LANKA Acknowledgements This report was written by Elizabeth Fraser with Frédéric Mousseau and Anuradha Mittal. The views and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of The Oakland Institute alone and do not reflect opinions of the individuals and organizations that have sponsored and supported the work. Cover photo: Inter-Faith Women’s Group in solidarity protest with Pilavu residents, February 2017 © Tamil Guardian Design: Amymade Graphic Design Publisher: The Oakland Institute is an independent policy think tank bringing fresh ideas and bold action to the most pressing social, economic, and environmental issues. Copyright © 2017 by The Oakland Institute. This text may be used free of charge for the purposes of advocacy, campaigning, education, and research, provided that the source is acknowledged in full. The copyright holder requests that all such uses be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, reuse in other publications, or translation or adaptation, permission must be secured. For more information: The Oakland Institute PO Box 18978 Oakland, CA 94619 USA www.oaklandinstitute.org [email protected] Acronyms CID Criminal Investigation Department CPA Centre for Policy Alternatives CTA Counter Terrorism Act CTF Consultation Task Force on Reconciliation Mechanisms IDP Internally Displaced Person ITJP International Truth and Justice Project LTTE Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam OMP Office on Missing Persons PTA Prevention of Terrorism Act UNCAT United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment UNHRC United Nations Human Rights Council 3 www.oaklandinstitute.org Executive Summary In January 2015, Sri Lanka elected a new President. -

Floods and Affected Population

F l o o d s a n d A f f e c t e d P o p u l a t i o n Ja f f n a D i s t r i c t / N ov e m b e r - D e c e m b e r 2 0 0 8 J a f f n a Population Distribution by DS Division 2007 Legend Affected population reported by the Government Agent, Jaffna as at 30 November 2008 Area Detail Estimated Population in 2007 Legend 4,124 - 5,000 # of Affected Point Pedro Point Pedro Persons Sandilipay Tellipallai 5,001 - 1,0000 Sandilipay Tellipallai Karaveddy Karaveddy 500 - 1,0000 10,001 - 20,000 Kopay 10,001 - 20,000 Chankanai Uduvil Kopay 20,001 - 30,000 Karainagar Chankanai Uduvil Karainagar 20,001 - 30,000 30,001 - 50,000 30,001 - 40,000 Kayts 50,001 - 60,000 Kayts Kayts 40,001 - 50,000 Kayts Chavakachcheri 60,001 - 65,000 Kayts Chavakachcheri Kayts JaffnaNallur Jaffna Nallur Velanai 65,001 - 75,000 Velanai Velanai Maruthnkerny Velanai Maruthnkerny Velanai Velanai Velanai Velanai Note : Heavy rains that started on 22nd November 2008 have provoked floods in several districts of Sri Lanka, mainly Delft Delft Jaffna, Kilinochchi, Mullaitivu, Mannar Ü and Trincomalee. Ü Kilometers Kilometers This map focuses on affected areas in 0 10 20 western Jaffna as data has been 0 10 20 made available on a regular basis. Relief support was provided to ASAR Image Classification as at 27 November 2008 Legend affected populations by both the Government of Sri Lanka and Hydro-Classification agencies. -

“Lost in Translation”: a Study of the History of Sri Lankan Literature

Karunakaran / Lost in Translation “Lost in Translation”: A Study of the History of Sri Lankan Literature Shamila Karunakaran Abstract This paper provides an overview of the history of Sri Lankan literature from the ancient texts of the precolonial era to the English translations of postcolonial literature in the modern era. Sri Lanka’s book history is a cultural record of texts that contains “cultural heritage and incorporates everything that has survived” (Chodorow, 2006); however, Tamil language works are written with specifc words, ideas, and concepts that are unique to Sri Lankan culture and are “lost in translation” when conveyed in English. Keywords book history, translation iJournal - Journal Vol. 4 No. 1, Fall 2018 22 Karunakaran / Lost in Translation INTRODUCTION The phrase “lost in translation” refers to when the translation of a word or phrase does not convey its true or complete meaning due to various factors. This is a common problem when translating non-Western texts for North American and British readership, especially those written in non-Roman scripts. Literature and texts are tangible symbols, containing signifed cultural meaning, and they represent varying aspects of an existing international ethnic, social, or linguistic culture or group. Chodorow (2006) likens it to a cultural record of sorts, which he defnes as an object that “contains cultural heritage and incorporates everything that has survived” (pg. 373). In particular, those written in South Asian indigenous languages such as Tamil, Sanskrit, Urdu, Sinhalese are written with specifc words, ideas, and concepts that are unique to specifc culture[s] and cannot be properly conveyed in English translations. -

PRINCIPAL's PRIZE DAY REPORT 2004 Venerable Chairman

PRINCIPAL’S PRIZE DAY REPORT 2004 Venerable Chairman, Professor Hoole, Dr Mrs Hoole. Distinguished Guests, Old Boys, Parents & Friends St.John’s - nursed, nurtured and nourished by the dedication of an able band of missionary heads, magnificently stands today at the threshold of its 181st year of existence extending its frontiers in the field of education. It is observed that according to records of the college, the very first Prize Giving was ceremoniously held in the year 1891. From then onwards it continues to uphold and maintain this tradition giving it a pride of place in the life of the school. In this respect, we extend to you all a very warm and cordial welcome. Your presence this morning is a source of inspiration and encouragement. Chairman Sir, your association and attachment to the church & the school are almost a decade and a half institutionalizing yourself admirably well in both areas. We are indeed proudly elated by your appointment as our new Manager and look forward to your continued contribution in your office. It is indeed a distinct privilege to have in our midst today, Professor Samuel Ratnajeevan Herbert Hoole & Dr. Mrs. Dushyanthy Hoole as our Chief Guests on this memorable occasion. Professor Sir, you stand here before us as a distinguished old boy and unique in every respect, being the only person in service in this country as a Fellow of the Institute of Electrical & Electronics Engineering with the citation; for contributions to computational methods for design optimization of electrical devices. In addition you hold a higher Doctorate in the field. -

01. the Divisional Information

01. THE DIVISIONAL INFORMATION 01.1 INTRODUCTION Since Jaffna Division is located as the heart of the city in the Jaffna district, also as it is an urban region and covered with lagoon at three sides and linked to land at the other side. The regional development to be considered .In this connection the needed sector wise resources and developmental requirements are analyzed in details. 1. To develop the divisional economy using above resources. 2. Identifying the factors which prevent the economy development. 3. How to develop Jaffna region by eradicate the barriers. 01.2 BASIC INFORMATION OF AREA Divisional Secretariat Jaffna Electoral Division Jaffna Electoral Division No Ten (:10) District Jaffna No. of GN Divisions Twenty Eight (28) No. of Villages Fifty (50) No. of Families 17514 No. of Members 59997 Land Area 10.92sq .km In Land Water Area 0.39 sq.km Total Area 11.31 sq.km Resource Profile 2016 1 Divisional Secretariat - Jaffna 01.3 LOCATION Jaffna Divisional Secretariat division is situated in Jaffna district of North Province of Sri Lanka. NORTH –NALLUR DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT DIVISION PART OF EAST – NALLUR DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT DIVISION PART OF EAST SOUTH – PART OF WEST BY JAFFNA LAGOON ART OF WEST – VALI SOUTH WEST DIVISIONAL SECRETARIATDIVISION Jaffna peninsula is made of limestone as it was submerged under sea during the Miocene period. The limestone is grey, yellow and white porous type. The entire land mass is flat and lies at sea level. Within one mile of the city center is the island of Mandativu which is connected by a causway. -

Alumni Message from Principal Solomon in THIS NEWSLETTER

Rev. Dr. Davidsathananthan Solomon, Principal Jaffna College [email protected] Volume 1, Issue 1, 2017 IN THIS NEWSLETTER Chairperson Jaffna College Board Alumni Message from Principal Solomon Editor’s Greetings College Students Perform Well in Examinations Upgrade to Daniel Poor Library New Junior Vice Principal English Language Resources A Generous Gift for Physical Education Starting an English Laboratory WELCOME TO “STEPPING UP’ FROM THE CHAIR OF THE BOARD On behalf of the Jaffna College Board of Directors, welcome to this first E-newsletter for our College Alumni, Stepping Up. I congratulate Principal Solomon and Junior Vice-Principal Gladys Muthurajah for their initiative in starting Stepping Up. Their initiative has stepped up to the Board’s challenge to implement a new policy of stakeholder engagement with our Alumni. The Board has recently carried out an extensive review of our governance performance. Following best practice advice specifically for governance development in low-income nations like Sri Lanka, we have adopted a policy to improve our relationships with stakeholders. The Board is committed to work together with Alumni for the benefit of Jaffna College students and staff. I second the Principal’s invitation to you to visit the College. I am continually delighted when Alumni visit me to discuss the College’s development, how they might contribute, and express their interest in better understanding the Board’s role and responsibilities. The Board is committed to better informing you of our work, and looks forward to receiving your feedback. Board minutes are available to you in the Principal’s office, for your information. As a Board, we have been stepping up to meet the challenges facing us. -

Persistence of Caste in South India - an Analytical Study of the Hindu and Christian Nadars

Copyright by Hilda Raj 1959 , PERSISTENCE OF CASTE IN SOUTH INDIA - AN ANALYTICAL STUDY OF THE HINDU AND CHRISTIAN NADARS by Hilda Raj Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The American University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Signatures of Committee: . Chairman: D a t e ; 7 % ^ / < f / 9 < r f W58 7 a \ The American University Washington, D. 0. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am deeply thankful to the following members of my Dissertation Committee for their guidance and sug gestions generously given in the preparation of the Dissertation: Doctors Robert T. Bower, N. G. D. Joardar, Lawrence Krader, Harvey C. Moore, Austin Van der Slice (Chairman). I express my gratitude to my Guru in Sociology, the Chairman of the above Committee - Dr. Austin Van der Slice, who suggested ways for the collection of data, and methods for organizing and presenting the sub ject matter, and at every stage supervised the writing of my Dissertation. I am much indebted to the following: Dr. Horace Poleman, Chief of the Orientalia Di vision of the Library of Congress for providing facilities for study in the Annex of the Library, and to the Staff of the Library for their unfailing courtesy and readi ness to help; The Librarian, Central Secretariat-Library, New Delhi; the Librarian, Connemara Public Library, Madras; the Principal in charge of the Library of the Theological Seminary, Nazareth, for privileges to use their books; To the following for helping me to gather data, for distributing questionnaire forms, collecting them after completion and mailing them to my address in Washington: Lawrence Gnanamuthu (Bombay), Dinakar Gnanaolivu (Madras), S. -

April - June 2013

Issue No. 139 April - June 2013 There are growing tensions in northern Sri Lanka as Tamil people try to prevent the Sinhalese-dominated army from taking over their land. -Charles Haviland-BBC Human Rights Review : April - June Institute of Human Rights 2 INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Editorial 03 Current issues : Is a political solution necessary? ♦ 19th Amendment twin-pronged 05 ♦ President should stand by his assurances Media Freedom ♦ Uthayan office attacked 08 ♦ If Media are suppressed, Democracy will die 09 Situation in the North & East ♦ Concerns Over Northern Land Grab 10 ♦ Tension over army 'seizure' of Sri Lanka Jaffna land Rotten, Corrupt & Inefficient this regime could last for ever ♦ A tragedy that could have been avoided 13 ♦ Railway crossings need not be death traps 14 ♦ Electricity hikes ♦ Matale Graves 15 ♦ University unrest 17 ♦ Charges revealed 18 ♦ The Azad Salley Affair 19 Our moment of destiny ♦ A voice of Sanity 19 ♦ A Case for Best Legal Brains 20 Death in Police Custody ♦ A Disturbing Trend Of Police Brutality 21 ♦ An ordeal hard to forget 22 Defying the International Community ♦ US Questions Govt. 23 Articles : ♦ The Forthcoming Anarchy - Diluting the 13th Amendment 29 ♦ Burning of the Jaffna Library 30 Unit Reports : Education Unit 26 Rehabilitation Unit 27 Staff Information 28 Edited by Layout designed by Cover Page Pictures Leela Isaac Hashini Rajaratna Ceylon Today - 27/05/2013 Human Rights Review : April - June 2 Institute of Human Rights EDITORIAL 3 THE NEED TO EDUCATE THE PEOPLE “Educate and inform the whole mass of the people. They are the only sure reliance for the preservation of our liberty”. -

Bibliometric Phenomenon of Tamil Publications in Sri Lanka in 2005

Journal of the University Librarians... (Vol. 1 l),2007 Bibliometric phenomenon of Tamil Publications in Sri Lanka in 2005 The Author MAHESHWARAN, R BA (Hons.)(Peradeniya), MLS (Colombo) Senior Asst. Librarian, University of Peradeniya Abstract Bibliometric analyses have been camed out in various fields. There has been no Bibliometric Study done on Tamil literature. This study evaluates the usefulness of bibilometric applicatbn for the analysis of Sri Lankan Tamil Publicat;ons in the year 2005 only. This paper discusses the necessity of preparing a detailed bibliometric analysis of Sri Lankan Publications or analysis of same nature and prepares comprehensive complete bibliographical accounts of Sri Lankan Tamil Publications. It tries to provide an account on authors, publishers, geographical area of publishers and editor in Tamil literatry field. This study also evaluates the length, size, prtce and pagination of published Tamil pubhcations in Sri Lanka. This study will Journal of the University Librarians ... .. .. (Vol.1 1 ), 2007 urge the Tamils scholars and researchers or Post graduate students to starf analyse of Bibliometric study on Tamil literature in Sri Lanka. A total number of 65 authors have produced 77 Tamil publications which have been taken for this analysis. Out of 91 publications, 15% are edited publications. Most of the publications 40% is published in Colombo and the Traditional Tamil cities - Jaffna and Batticalo contributed 11% and 9% to the publishing field respectively. Most of the Muslim origin publications were published in the Eastern Provincial Region amounting to 15% and the Upcountry area contributed to the Tamil Publication with 16%. 15%of the publications are brought about by the authors. -

Tides of Violence: Mapping the Sri Lankan Conflict from 1983 to 2009 About the Public Interest Advocacy Centre

Tides of violence: mapping the Sri Lankan conflict from 1983 to 2009 About the Public Interest Advocacy Centre The Public Interest Advocacy Centre (PIAC) is an independent, non-profit legal centre based in Sydney. Established in 1982, PIAC tackles barriers to justice and fairness experienced by people who are vulnerable or facing disadvantage. We ensure basic rights are enjoyed across the community through legal assistance and strategic litigation, public policy development, communication and training. 2nd edition May 2019 Contact: Public Interest Advocacy Centre Level 5, 175 Liverpool St Sydney NSW 2000 Website: www.piac.asn.au Public Interest Advocacy Centre @PIACnews The Public Interest Advocacy Centre office is located on the land of the Gadigal of the Eora Nation. TIDES OF VIOLENCE: MAPPING THE SRI LANKAN CONFLICT FROM 1983 TO 2009 03 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................... 09 Background to CMAP .............................................................................................................................................09 Report overview .......................................................................................................................................................09 Key violation patterns in each time period ......................................................................................................09 24 July 1983 – 28 July 1987 .................................................................................................................................10