Density Bonusing and Development in Toronto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agenda Item History - 2013.MM41.25

Agenda Item History - 2013.MM41.25 http://app.toronto.ca/tmmis/viewAgendaItemHistory.do?item=2013.MM... Item Tracking Status City Council adopted this item on November 13, 2013 with amendments. City Council consideration on November 13, 2013 MM41.25 ACTION Amended Ward:All Requesting Mayor Ford to respond to recent events - by Councillor Denzil Minnan-Wong, seconded by Councillor Peter Milczyn City Council Decision Caution: This is a preliminary decision. This decision should not be considered final until the meeting is complete and the City Clerk has confirmed the decisions for this meeting. City Council on November 13 and 14, 2013, adopted the following: 1. City Council request Mayor Rob Ford to apologize for misleading the City of Toronto as to the existence of a video in which he appears to be involved in the use of drugs. 2. City Council urge Mayor Rob Ford to co-operate fully with the Toronto Police in their investigation of these matters by meeting with them in order to respond to questions arising from their investigation. 3. City Council request Mayor Rob Ford to apologize for writing a letter of reference for Alexander "Sandro" Lisi, an alleged drug dealer, on City of Toronto Mayor letterhead. 4. City Council request Mayor Ford to answer to Members of Council on the aforementioned subjects directly and not through the media. 5. City Council urge Mayor Rob Ford to take a temporary leave of absence to address his personal issues, then return to lead the City in the capacity for which he was elected. 6. City Council request the Integrity Commissioner to report back to City Council on the concerns raised in Part 1 through 5 above in regard to the Councillors' Code of Conduct. -

Breathing Life Back Into Yonge St

JARVIS AND CHARLES SHERWAY GARDENS Move in ONLY 5% DOWN ONLY 5% DOWN UP TO $10,000 OFF* UP TO $20,000 CASH BACK** x2condos.com onesherway.com this year. Man cave makeover A pool table and ‘wine bar’? *$10,000 discount on select suites. **$20,000 cash back on select suites. Limited time offer. Subject to change or withdrawal without notice. See sales agent for details. Exclusive listing, Baker Real Estate Incorporated, Brokerage. Brokers protected. All illustrations are artists’ concept. Prices, sizes and specifications subject to change without notice. E.&O.E. Yes, says Glen Peloso, H11 IN HOMES CONDOS NEW SATURDAY, APRIL 26, 2014 SECTION H EA ON2 Breathing life back into Yonge St. RYAN STARR SPECIAL TO THE STAR Canada’s tallest condo among projects revitalizing Toronto’s main, historic street Aura is changing the way we view our city. The 78-storey megatower, nearing com- pletion on the northwest corner of Yonge and Gerrard Sts., has fast become one of Toronto most recognizable landmarks. “You notice it from the 401and Dufferin, or coming down the DVP,” notes Barry Graziani, the architect whose firm Grazia- ni & Corraza designed Aura, Canada’s tall- est residential building. “It reorients you — there’s the financial district and then there’s Aura farther north. It’s expanding our sense of the city and the downtown core.” Visible from across the GTA, the building also proudly signals that the once-gloomy stretch of Yonge between Gerrard and College Sts. has suddenly become a big deal. Indeed, Aura, developed by Canderel Residential, has helped spur a transforma- tion of the area, a historic part of the city that had fallen into disrepair over the years. -

One Yonge: a Case Study for Complete Vertical Communities

ctbuh.org/papers Title: One Yonge: A Case Study for Complete Vertical Communities Author: David Pontarini, Principal, Hariri Pontarini Architects Subjects: Architectural/Design Urban Design Keywords: Economics Urban Planning Publication Date: 2016 Original Publication: Cities to Megacities: Shaping Dense Vertical Urbanism Paper Type: 1. Book chapter/Part chapter 2. Journal paper 3. Conference proceeding 4. Unpublished conference paper 5. Magazine article 6. Unpublished © Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat / David Pontarini One Yonge: A Case Study for Complete Vertical Communities 央街一号:垂直社区一例 Abstract | 摘要 David Pontarini 大卫 庞特里尼 Principal | 创始人、合伙人 The City of Toronto is experiencing rapid growth, with the second largest concentration of high-rise buildings under construction in North America, surpassing Chicago and coming in Hariri Pontarini Architects Hariri Pontarini建筑师事务所 just under New York City. Provincial strategies have encouraged this intensification, including areas like the Yonge Street Corridor. This paper outlines the narrative of the One Yonge project by Toronto | 多伦多 Hariri Pontarini Architects (HPR), which is located at the foot of Toronto’s Yonge Street. The five- David Pontarini, Founding Partner of Hariri Pontarini Architects (HPA), focuses on building better cities through quality urban tower, mixed-use development has a footprint of 26,996 square meters, with its tallest structure developments that channel the best aspects of their site and rising to a height of 303 meters. One Yonge is being developed as part of a larger precinct plan program into finely executed architectural and public realm designs. Over the past 30 years, he has built an award-winning organized by the City and Waterfront Toronto. -

Toronto Taxpayers Coalition 2014 Councillor Report Card

Toronto Taxpayers Coalition 2014 Councillor Report Card Rob Ford Mayor of Toronto GRADE: KEY VOTES Supported Scarborough Subway Supported Coalition petition to cut council in half Supported elimination of $2 million spending increase Supported eliminating council general expense budgets Supported report on reducing land transfer tax by 5% COMMENTS Mayor Ford presided over a remarkable term of council, enjoying many policy victories to deliver savings but re- mained unable to deliver on several key promis- es. Penalized for some bad behaviour. The Toronto Taxpayers Coalition is a non- partisan advocate for lower taxes and reduced spending. Find out more and join today at www.torontotaxpayer.ca Toronto Taxpayers Coalition 2014 Councillor Report Card Vincent Crisanti Ward 1 Etobicoke North GRADE: KEY VOTES Supported Scarborough Subway Supported Coalition petition to cut council in half Supported elimination of $2 million spending increase Supported eliminating council general expense budgets Supported report on reducing land transfer tax by 5% COMMENTS Councillor Crisanti remains a champion of Coalition initia- tives, but we would like him to be a more vocal advocate during council debates and in the media. The Toronto Taxpayers Coalition is a non- partisan advocate for lower taxes and reduced spending. Find out more and join today at www.torontotaxpayer.ca Toronto Taxpayers Coalition 2014 Councillor Report Card Doug Ford Ward 2 Etobicoke North GRADE: KEY VOTES Supported Scarborough Subway Supported Coalition petition to cut council in half Supported elimination of $2 million spending increase Supported eliminating council general expense budgets Supported report on reducing land transfer tax by 5% COMMENTS Councillor Ford is a tireless advocate for taxpayers but continues to be baited by political adversaries. -

Item MM37.16

Agenda Item History - 2013.MM37.16 http://app.toronto.ca/tmmis/viewAgendaItemHistory.do?item=2013.MM... Item Tracking Status City Council adopted this item on July 16, 2013 without amendments. City Council consideration on July 16, 2013 MM37.16 ACTION Adopted Ward:All Protecting the Great Lakes from Invasive Species: Asian Carp - by Councillor Mike Layton, seconded by Councillor Paul Ainslie City Council Decision City Council on July 16, 17, 18 and 19, 2013, adopted the following: 1. City Council write a letter to the Federal and Provincial Ministers of the Environment strongly urging all parties to work in cooperation with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, to identify a preferred solution to the invasive carp issue and move forward to implement that solution with the greatest sense of urgency. Background Information (City Council) Member Motion MM37.16 (http://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2013/mm/bgrd/backgroundfile-60220.pdf) Communications (City Council) (July 10, 2013) Letter from Dr. Terry Quinney, Provincial Manager, Fish and Wildlife Services, Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters (MM.Supp.MM37.16.1) (http://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2013/mm/comm/communicationfile-39105.pdf) (July 12, 2013) Letter from Dr. Mark Gloutney, Director of Regional Operations - Eastern Region, Ducks Unlimited Canada (MM.Supp.MM37.16.2) (http://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2013/mm/comm/communicationfile-39106.pdf) (July 12, 2013) E-mail from Terry Rees, Executive Director, Federation of Ontario Cottagers' Association (MM.Supp.MM37.16.3) (http://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2013/mm/comm/communicationfile-39097.pdf) (July 16, 2013) Letter from Bob Kortright, Past President, Toronto Field Naturalists (MM.New.MM37.16.4) (http://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2013/mm/comm/communicationfile-39184.pdf) Motions (City Council) Motion to Waive Referral (Carried) Speaker Nunziata advised Council that the provisions of Chapter 27, Council Procedures, require that Motion MM37.16 be referred to the Executive Committee. -

Planning & Urban Design Rationale

DRAWING NOT TO BE SCALED Contractor must check and verify all dimensions on the job and report any discrepancies to the architect before proceeding with the work. 11 YORKVILLE AVENUE This drawing shall not be used for construction purposes until signed by the consultant responsible. This drawing, as an instrument of service, is provided by and is the property of REZONING AND SPA APPLICATION Sweeny & Co. Architects. ISSUED / REVISED NOV 28,17 ISSUED FOR REVIEW JAN 16,18 ISSUED FOR REVIEW JAN 26,18 ISSUED FOR COORDINATION MAR 02,18 ISSUED FOR COORDINATION MAR 21,18 ISSUED FOR REVIEW MARCH 18 PLANNING 11–21 YORKVILLE AVENUE & & URBAN 16–18 CUMBERLAND STREET DESIGN CIT Y O F TORONTO RATIONALE PREPARED FOR: 11–21 Y ORKVILLE P ARTNERS I NC . List of Drawings A000 Cover Page A001 Development Statistics A002 Development Statistics A003 Zoning Gross Floor Area Bylaw 569-2013 Building A A004 Zoning Gross Floor Area Bylaw 569-2013 Building A A005 Zoning Gross Floor Area Bylaw 438-86 Building A 134 PETER STREET | SUITE 1601 A006 Zoning Gross Floor Area Bylaw 438-86 Building A TORONTO, ONTARIO | M5V 2H2 | CANADA P: 416-971-6252 | F: 416-971-5420 A007 Zoning Gross Floor Area Building B E: [email protected] | www.sweenyandco.com A008 Survey A100 Site Plan PROJ. NAME A101 P4 Floor Plan A102 P3 Floor Plan Mixed-Use A103 P2 Floor Plan Development A104 P1 Floor Plan le_Central_mahtabEHFF9.rvt 11-21 Yorkville Avenue, A105 Concourse Floor Plan 16-18 Cumberland Street A106 Ground Floor Plan A107 Ground Floor Mezzanine Floor Plan OWNER A108 Second Floor Retail Plan A109 3rd Floor Plan - Amenity 11 Yorkville Partners A110 4th Floor Plan - Amenity Inc. -

Funding Arts and Culture Top-10 Law Firms

TORONTO EDITION FRIDAY, DECEMBER 16, 2016 Vol. 20 • No. 49 2017 budget overview 19th annual Toronto rankings FUNDING ARTS TOP-10 AND CULTURE DEVELOPMENT By Leah Wong LAW FIRMS To meet its 2017 target of $25 per capita spending in arts and culture council will need to, not only waive its 2.6 per cent reduction target, but approve an increase of $2.2-million in the It was another busy year at the OMB for Toronto-based 2017 economic development and culture budget. appeals. With few developable sites left in the city’s growth Economic development and culture manager Michael areas, developers are pushing forward with more challenging Williams has requested a $61.717-million net operating proposals such as the intensifi cation of existing apartment budget for 2017, a 3.8 per cent increase over last year. neighbourhoods, the redevelopment of rental apartments with Th e division’s operating budget allocates funding to its implications for tenant relocation, and the redevelopment of four service centres—art services (60 per cent), museum and existing towers such as the Grand Hotel, to name just a few. heritage services (18 per cent), business services (14 per cent) While only a few years ago a 60-storey tower proposal and entertainment industries services (8 per cent). may have seemed stratospheric, the era of the supertall tower One of the division’s major initiatives for 2017 is the city’s has undeniably arrived. In last year’s Toronto law review, the Canada 150 celebrations. At the end of 2017 with the Canada 82- and 92-storey Mirvish + Gehry towers were the tallest 150 initiatives completed, $4.284-million in one-time funding buildings brought before the board. -

Escribe Agenda Package

Executive Committee Meeting #5/17 was held at TRCA Head Office, on Friday, July 14, 2017. The Chair Maria Augimeri, called the meeting to order at 9:31 a.m. PRESENT Maria Augimeri Chair Jack Heath Vice Chair Jack Ballinger Member Vincent Crisanti Member Jennifer Innis Member Mike Mattos Member Jennifer McKelvie Member PRESENT VIA TELECONFERENCE Colleen Jordan Member ABSENT Glenn De Baeremaeker Member Chris Fonseca Member Anthony Perruzza Member RES.#B56/17 - MINUTES Moved by: Jennifer McKelvie Seconded by: Mike Mattos THAT the Minutes of Meeting #4/17, held on June 9, 2017, be approved. CARRIED ______________________________ 279 Section I – Items for Authority Action RES.#B57/17 - GREENLANDS ACQUISITION PROJECT FOR 2016-2020 Flood Plain and Conservation Component, Don River Watershed Quadrant Holdings Inc., CFN 57972. Acquisition of property located north of Rutherford Road and west of Bathurst Street, in the City of Vaughan, Regional Municipality of York, under the “Greenlands Acquisition Project for 2016-2020,” Flood Plain and Conservation Component, Don River watershed. Moved by: Vincent Crisanti Seconded by: Colleen Jordan THE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE RECOMMENDS THAT 0.93 hectares (2.29 acres), more or less, of vacant land, located north of Rutherford Road and west of Bathurst Street, said land being Part of Lots 17 and 18, Concession 2 designated as Part 19 on Plan 65M-4540 and Parts 19 and 20 on Plan 65M-4541, in the City of Vaughan, Regional Municipality of York, be purchased from Quadrant Holdings Inc.; THAT the purchase price be $2.00; THAT Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA) receive conveyance of the land free from encumbrance, subject to existing service easements; THAT the firm, Gardiner Roberts LLP be instructed to complete the transaction at the earliest possible date. -

Agenda Toronto Transit Commission

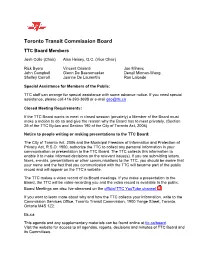

Agenda Toronto Transit Commission Meeting No. 2000 Monday, July 11, 2016 10 a.m. – Public Session Recess 12 p.m. – 1 p.m. Reconvene 1 p.m. Committee Room #1 Toronto City Hall, 100 Queen Street West Board Meetings are live-streamed on the official TTC YouTube channel TTC Board Members Josh Colle (Chair) Alan Heisey, QC (Vice-Chair) John Campbell Rick Byers Vincent Crisanti Shelley Carroll Ron Lalonde Glenn De Baeremaeker Denzil Minnan-Wong Joe Mihevc Declarations of Interest - Municipal Conflict of Interest Act Resolution to conduct a portion of the meeting in the absence of the public (Committee of the Whole) in accordance with Section 29 of the TTC By-law to Govern Commission Proceedings and Section 190 of the City of Toronto Act. Minutes of the Previous Meeting - Meeting No. 1998 - Wednesday, April 27, 2016 (Joint Metrolinx-TTC meeting) - Meeting No. 1999 - Tuesday, May 31, 2016 Business Arising Out of Minutes Public Presentations Requests to speak must be registered by noon of the business day preceding meeting day. A final deputation list will be distributed at the meeting. Board Meeting No. 2000 Agenda Page 1 Monday, July 11, 2016 Presentations/Reports/Other Business 1. Toronto-York Spadina Subway Extension Settlement of Claim - Contract A65-29 - Track Installation (This report contains advice or communications that are subject to Solicitor-Client Privilege) (For Action) 1(a) Toronto-York Spadina Subway Extension (TYSSE) Claims Settlement Update (This report contains advice or communications that are subject to Solicitor-Client Privilege) (For Action) 2. Bombardier Streetcars - Claims Update (This report contains advice or communications that are subject to Solicitor-Client Privilege) (For Action) 3. -

Audit and Risk Management Minutes

Toronto Transit Commission Board TTC Board Members Josh Colle (Chair) Alan Heisey, Q.C. (Vice Chair) Rick Byers Vincent Crisanti Joe Mihevc John Campbell Glenn De Baeremaeker Denzil Minnan-Wong Shelley Carroll Joanne De Laurentiis Ron Lalonde Special Assistance for Members of the Public: TTC staff can arrange for special assistance with some advance notice. If you need special assistance, please call 416-393-3698 or e-mail [email protected] Closed Meeting Requirements: If the TTC Board wants to meet in closed session (privately) a Member of the Board must make a motion to do so and give the reason why the Board has to meet privately. (Section 29 of the TTC By-law and Section 190 of the City of Toronto Act, 2006) Notice to people writing or making presentations to the TTC Board: The City of Toronto Act, 2006 and the Municipal Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act, R.S.O. 1900, authorize the TTC to collect any personal information in your communication or presentation to the TTC Board. The TTC collects this information to enable it to make informed decisions on the relevant issue(s). If you are submitting letters, faxes, e-mails, presentations or other communications to the TTC, you should be aware that your name and the fact that you communicated with the TTC will become part of the public record and will appear on the TTC’s website. The TTC makes a video record of its Board meetings. If you make a presentation to the Board, the TTC will be video-recording you and the video record is available to the public. -

Affordable/Social Housing Developments, City of Toronto

Social Infrastructure Fund: Affordable/Social Housing Developments, City of Toronto Total City of Toronto Funding: $154.251M 2016-18 Social Housing Improvements Program (SHIP)* $72.2 M * All programs except SHIP are cost-shared with Ontario Housing Allowances ** $29.7 M ** Housing Allowances are available throughout the City to qualifying households New Rental Housing $27.1 M *** Toronto Renovates includes funding for qualifying senior homeowners throughout the City Homeownership Assistance $9.1 M Toronto Renovates *** $8.3 M Program Administration Funds $7.8 M Total $154.2 M City of Toronto Ward Councillor Project Address Program SIF Funding Ward 1 - Etobicoke North Vincent Crisanti ACLI Etobicoke Community Homes Inc 88 Humber College Boulevard Social Housing Improvements $ 61,705 Our Saviour Thistletown Lutheran Lodge 2715 Islington Avenue Social Housing Improvements $ 271,697 Maurice Coulter Housing Co-operative 174 John Garland Boulevard Social Housing Improvements $ 719,550 Toronto Community Housing Corporation 2765 Islington Avenue Social Housing Improvements $ 1,600,000 Toronto Community Housing Corporation 15-268 Jamestown Crescent Social Housing Improvements $ 1,203,216 Ward 2 - Etobicoke North Michael Ford Ascot Co-operative Homes Inc 930 Queens Plate Drive Social Housing Improvements $ 417,688 Ward 4 - Etobicoke Centre John Campbell Richview Baptist Foundation 1540 Kipling Avenue Social Housing Improvements $ 405,900 Ward 6 - Etobicoke-Lakeshore Mark Grimes Lakeshore Gardens Co-operative Homes Inc 10 Garnett Janes Road Social Housing Improvements $ 371,988 Ward 7 - York West Giorgio Mammoliti Glen Gardens Housing Co-operative Inc 2750 Jane Street Social Housing Improvements $ 419,738 Ward 8 - York West Anthony Perruzza Toronto Community Housing Corporation 40-10 Driftwood Avenue Social Housing Improvements $ 500,000 Ward 9 - York Centre Maria Augimeri Palisades Housing Co-Operative Inc 1206 Wilson Avenue Social Housing Improvements $ 85,588 Ward 10 - York Centre James Pasternak Shiplake Properties 30 Tippett Rd. -

Escribe Agenda Package

Executive Committee Meeting Agenda #7/16 September 9, 2016 9:30 A.M. HEAD OFFICE, 101 EXCHANGE AVENUE, VAUGHAN Members: Chair Maria Augimeri Vice Chair Michael Di Biase Jack Ballinger David Barrow Vincent Crisanti Glenn De Baeremaeker Chris Fonseca Jennifer Innis Colleen Jordan Giorgio Mammoliti Mike Mattos Ron Moeser Pages 1. MINUTES OF MEETING #6/16, HELD ON AUGUST 5, 2016 Link to Executive Committee Minutes 2. BUSINESS ARISING FROM THE MINUTES 3. DISCLOSURE OF PECUNIARY INTEREST AND THE GENERAL NATURE THEREOF 4. DELEGATIONS 5. PRESENTATIONS 1 6. CORRESPONDENCE 6.1 A submission dated July 12, 2016 from Ms. Jane Fairburn, resident, 7 Scarborough, in regard to Scarborough Waterfront Development Project. 6.2 A submission dated August 29, 2016 from Mr. Roy Wright, resident, 13 Scarborough, in regard to the Scarborough Waterfront Project. 7. SECTION I - ITEMS FOR AUTHORITY ACTION 7.1 GREENLANDS ACQUISITION PROJECT FOR 2016-2020 15 Acquisition for the Jennifer Court Erosion Control Project, Humber River Watershed 2 and 4 Jennifer Court, City of Toronto CFN 55065 and CFN 55066 7.2 GREENLANDS ACQUISITION PROJECT FOR 2016-2020 18 Flood Plain and Conservation Component, Humber River Watershed Bolton Gateway Developments Inc. CFN 56266 7.3 GREENLANDS ACQUISITION PROJECT FOR 2016-2020 21 Flood Plain and Conservation Component, Humber River Watershed PowerStream Inc. CFN 56094 7.4 GREENLANDS ACQUISITION PROJECT FOR 2016-2020 24 Flood Plain and Conservation Component, Duffins Creek Watershed Oxford Homes CFN 56293 7.5 GREENLANDS ACQUISITION PROJECT FOR 2016-2020 27 Flood Plain and Conservation Component, Don River Watershed Longyard Properties Inc. CFN 56432 8.