Bulletin of the California Lichen Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lepraria Normandinoides

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ ISSN 2307-8235 (online) IUCN 2020: T180096955A180097006 Scope(s): Global Language: English Lepraria normandinoides Assessment by: Lendemer, J. View on www.iucnredlist.org Citation: Lendemer, J. 2020. Lepraria normandinoides. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T180096955A180097006. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020- 3.RLTS.T180096955A180097006.en Copyright: © 2020 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale, reposting or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holder. For further details see Terms of Use. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ is produced and managed by the IUCN Global Species Programme, the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) and The IUCN Red List Partnership. The IUCN Red List Partners are: Arizona State University; BirdLife International; Botanic Gardens Conservation International; Conservation International; NatureServe; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Sapienza University of Rome; Texas A&M University; and Zoological Society of London. If you see any errors or have any questions or suggestions on what is shown in this document, please provide us with feedback so that we can correct or extend the information provided. THE IUCN RED LIST OF THREATENED SPECIES™ Taxonomy Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Fungi Ascomycota Lecanoromycetes Lecanorales Stereocaulaceae Scientific Name: Lepraria normandinoides Lendemer & R.C. Harris Taxonomic Source(s): Index Fungorum Partnership. 2020. Index Fungorum. Available at: http://www.indexfungorum.org. -

Global Biodiversity Patterns of the Photobionts Associated with the Genus Cladonia (Lecanorales, Ascomycota)

Microbial Ecology https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-020-01633-3 FUNGAL MICROBIOLOGY Global Biodiversity Patterns of the Photobionts Associated with the Genus Cladonia (Lecanorales, Ascomycota) Raquel Pino-Bodas1 & Soili Stenroos2 Received: 19 August 2020 /Accepted: 22 October 2020 # The Author(s) 2020 Abstract The diversity of lichen photobionts is not fully known. We studied here the diversity of the photobionts associated with Cladonia, a sub-cosmopolitan genus ecologically important, whose photobionts belong to the green algae genus Asterochloris. The genetic diversity of Asterochloris was screened by using the ITS rDNA and actin type I regions in 223 specimens and 135 species of Cladonia collected all over the world. These data, added to those available in GenBank, were compiled in a dataset of altogether 545 Asterochloris sequences occurring in 172 species of Cladonia. A high diversity of Asterochloris associated with Cladonia was found. The commonest photobiont lineages associated with this genus are A. glomerata, A. italiana,andA. mediterranea. Analyses of partitioned variation were carried out in order to elucidate the relative influence on the photobiont genetic variation of the following factors: mycobiont identity, geographic distribution, climate, and mycobiont phylogeny. The mycobiont identity and climate were found to be the main drivers for the genetic variation of Asterochloris. The geographical distribution of the different Asterochloris lineages was described. Some lineages showed a clear dominance in one or several climatic regions. In addition, the specificity and the selectivity were studied for 18 species of Cladonia. Potentially specialist and generalist species of Cladonia were identified. A correlation was found between the sexual reproduction frequency of the host and the frequency of certain Asterochloris OTUs. -

Pronectria Rhizocarpicola, a New Lichenicolous Fungus from Switzerland

Mycosphere 926–928 (2013) ISSN 2077 7019 www.mycosphere.org Article Mycosphere Copyright © 2013 Online Edition Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/4/5/4 Pronectria rhizocarpicola, a new lichenicolous fungus from Switzerland Brackel WV Wolfgang von Brackel, Institut für Vegetationskunde und Landschaftsökologie, Georg-Eger-Str. 1b, D-91334 Hemhofen, Germany. – e-mail: [email protected] Brackel WV 2013 – Pronectria rhizocarpicola, a new lichenicolous fungus from Switzerland. Mycosphere 4(5), 926–928, Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/4/5/4 Abstract Pronectria rhizocarpicola, a new species of Bionectriaceae is described and illustrated. It is growing parasitically on Rhizocarpon geographicum in the Swiss Alps. Key words – Ascomycota – bionectriaceae – hypocreales Introduction The genus Pronectria currently comprises 44 species, including 2 algicolous and 42 lichenicolous species. Most of the lichenicolous species are living on foliose and fruticose lichens (32 species), only a few on squamulose and crustose lichens (10 species). No species of the genus was ever reported from the host genus Rhizocarpon. Materials and methods Morphological and anatomical observations were made using standard microscopic techniques. Microscopic measurements were made on hand-cut sections mounted in water with an accuracy up to 0.5 µm. Measurements of ascospores and asci are recorded as (minimum–) X-σ X – X+σ X (–maximum) followed by the number of measurements. The holotype is deposited in M, one isotype in the private herbarium of the author (hb ivl). Results Pronectria rhizocarpicola Brackel, sp. nov. Figs 1–2 MycoBank 805068 Etymology – pertaining to the host genus Rhizocarpon. Diagnosis – Fungus lichenicola in thallo et ascomatibus lichenis Rhizocarpon geographicum crescens. -

Mycosphere Notes 225–274: Types and Other Specimens of Some Genera of Ascomycota

Mycosphere 9(4): 647–754 (2018) www.mycosphere.org ISSN 2077 7019 Article Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/9/4/3 Copyright © Guizhou Academy of Agricultural Sciences Mycosphere Notes 225–274: types and other specimens of some genera of Ascomycota Doilom M1,2,3, Hyde KD2,3,6, Phookamsak R1,2,3, Dai DQ4,, Tang LZ4,14, Hongsanan S5, Chomnunti P6, Boonmee S6, Dayarathne MC6, Li WJ6, Thambugala KM6, Perera RH 6, Daranagama DA6,13, Norphanphoun C6, Konta S6, Dong W6,7, Ertz D8,9, Phillips AJL10, McKenzie EHC11, Vinit K6,7, Ariyawansa HA12, Jones EBG7, Mortimer PE2, Xu JC2,3, Promputtha I1 1 Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand 2 Key Laboratory for Plant Diversity and Biogeography of East Asia, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 132 Lanhei Road, Kunming 650201, China 3 World Agro Forestry Centre, East and Central Asia, 132 Lanhei Road, Kunming 650201, Yunnan Province, People’s Republic of China 4 Center for Yunnan Plateau Biological Resources Protection and Utilization, College of Biological Resource and Food Engineering, Qujing Normal University, Qujing, Yunnan 655011, China 5 Shenzhen Key Laboratory of Microbial Genetic Engineering, College of Life Sciences and Oceanography, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen 518060, China 6 Center of Excellence in Fungal Research, Mae Fah Luang University, Chiang Rai 57100, Thailand 7 Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology, Faculty of Agriculture, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand 8 Department Research (BT), Botanic Garden Meise, Nieuwelaan 38, BE-1860 Meise, Belgium 9 Direction Générale de l'Enseignement non obligatoire et de la Recherche scientifique, Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles, Rue A. -

H. Thorsten Lumbsch VP, Science & Education the Field Museum 1400

H. Thorsten Lumbsch VP, Science & Education The Field Museum 1400 S. Lake Shore Drive Chicago, Illinois 60605 USA Tel: 1-312-665-7881 E-mail: [email protected] Research interests Evolution and Systematics of Fungi Biogeography and Diversification Rates of Fungi Species delimitation Diversity of lichen-forming fungi Professional Experience Since 2017 Vice President, Science & Education, The Field Museum, Chicago. USA 2014-2017 Director, Integrative Research Center, Science & Education, The Field Museum, Chicago, USA. Since 2014 Curator, Integrative Research Center, Science & Education, The Field Museum, Chicago, USA. 2013-2014 Associate Director, Integrative Research Center, Science & Education, The Field Museum, Chicago, USA. 2009-2013 Chair, Dept. of Botany, The Field Museum, Chicago, USA. Since 2011 MacArthur Associate Curator, Dept. of Botany, The Field Museum, Chicago, USA. 2006-2014 Associate Curator, Dept. of Botany, The Field Museum, Chicago, USA. 2005-2009 Head of Cryptogams, Dept. of Botany, The Field Museum, Chicago, USA. Since 2004 Member, Committee on Evolutionary Biology, University of Chicago. Courses: BIOS 430 Evolution (UIC), BIOS 23410 Complex Interactions: Coevolution, Parasites, Mutualists, and Cheaters (U of C) Reading group: Phylogenetic methods. 2003-2006 Assistant Curator, Dept. of Botany, The Field Museum, Chicago, USA. 1998-2003 Privatdozent (Assistant Professor), Botanical Institute, University – GHS - Essen. Lectures: General Botany, Evolution of lower plants, Photosynthesis, Courses: Cryptogams, Biology -

BLS Bulletin 111 Winter 2012.Pdf

1 BRITISH LICHEN SOCIETY OFFICERS AND CONTACTS 2012 PRESIDENT B.P. Hilton, Beauregard, 5 Alscott Gardens, Alverdiscott, Barnstaple, Devon EX31 3QJ; e-mail [email protected] VICE-PRESIDENT J. Simkin, 41 North Road, Ponteland, Newcastle upon Tyne NE20 9UN, email [email protected] SECRETARY C. Ellis, Royal Botanic Garden, 20A Inverleith Row, Edinburgh EH3 5LR; email [email protected] TREASURER J.F. Skinner, 28 Parkanaur Avenue, Southend-on-Sea, Essex SS1 3HY, email [email protected] ASSISTANT TREASURER AND MEMBERSHIP SECRETARY H. Döring, Mycology Section, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 3AB, email [email protected] REGIONAL TREASURER (Americas) J.W. Hinds, 254 Forest Avenue, Orono, Maine 04473-3202, USA; email [email protected]. CHAIR OF THE DATA COMMITTEE D.J. Hill, Yew Tree Cottage, Yew Tree Lane, Compton Martin, Bristol BS40 6JS, email [email protected] MAPPING RECORDER AND ARCHIVIST M.R.D. Seaward, Department of Archaeological, Geographical & Environmental Sciences, University of Bradford, West Yorkshire BD7 1DP, email [email protected] DATA MANAGER J. Simkin, 41 North Road, Ponteland, Newcastle upon Tyne NE20 9UN, email [email protected] SENIOR EDITOR (LICHENOLOGIST) P.D. Crittenden, School of Life Science, The University, Nottingham NG7 2RD, email [email protected] BULLETIN EDITOR P.F. Cannon, CABI and Royal Botanic Gardens Kew; postal address Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 3AB, email [email protected] CHAIR OF CONSERVATION COMMITTEE & CONSERVATION OFFICER B.W. Edwards, DERC, Library Headquarters, Colliton Park, Dorchester, Dorset DT1 1XJ, email [email protected] CHAIR OF THE EDUCATION AND PROMOTION COMMITTEE: S. -

Lichens and Associated Fungi from Glacier Bay National Park, Alaska

The Lichenologist (2020), 52,61–181 doi:10.1017/S0024282920000079 Standard Paper Lichens and associated fungi from Glacier Bay National Park, Alaska Toby Spribille1,2,3 , Alan M. Fryday4 , Sergio Pérez-Ortega5 , Måns Svensson6, Tor Tønsberg7, Stefan Ekman6 , Håkon Holien8,9, Philipp Resl10 , Kevin Schneider11, Edith Stabentheiner2, Holger Thüs12,13 , Jan Vondrák14,15 and Lewis Sharman16 1Department of Biological Sciences, CW405, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta T6G 2R3, Canada; 2Department of Plant Sciences, Institute of Biology, University of Graz, NAWI Graz, Holteigasse 6, 8010 Graz, Austria; 3Division of Biological Sciences, University of Montana, 32 Campus Drive, Missoula, Montana 59812, USA; 4Herbarium, Department of Plant Biology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan 48824, USA; 5Real Jardín Botánico (CSIC), Departamento de Micología, Calle Claudio Moyano 1, E-28014 Madrid, Spain; 6Museum of Evolution, Uppsala University, Norbyvägen 16, SE-75236 Uppsala, Sweden; 7Department of Natural History, University Museum of Bergen Allégt. 41, P.O. Box 7800, N-5020 Bergen, Norway; 8Faculty of Bioscience and Aquaculture, Nord University, Box 2501, NO-7729 Steinkjer, Norway; 9NTNU University Museum, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, NO-7491 Trondheim, Norway; 10Faculty of Biology, Department I, Systematic Botany and Mycology, University of Munich (LMU), Menzinger Straße 67, 80638 München, Germany; 11Institute of Biodiversity, Animal Health and Comparative Medicine, College of Medical, Veterinary and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8QQ, UK; 12Botany Department, State Museum of Natural History Stuttgart, Rosenstein 1, 70191 Stuttgart, Germany; 13Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, UK; 14Institute of Botany of the Czech Academy of Sciences, Zámek 1, 252 43 Průhonice, Czech Republic; 15Department of Botany, Faculty of Science, University of South Bohemia, Branišovská 1760, CZ-370 05 České Budějovice, Czech Republic and 16Glacier Bay National Park & Preserve, P.O. -

A Review of Lichenology in Saint Lucia Including a Lichen Checklist

A REVIEW OF LICHENOLOGY IN SAINT LUCIA INCLUDING A LICHEN CHECKLIST HOWARD F. FOX1 AND MARIA L. CULLEN2 Abstract. The lichenological history of Saint Lucia is reviewed from published literature and catalogues of herbarium specimens. 238 lichens and 2 lichenicolous fungi are reported. Of these 145 species are known only from single localities in Saint Lucia. Important her- barium collections were made by Alexander Evans, Henry and Frederick Imshaug, Dag Øvstedal, Emmanuël Sérusiaux and the authors. Soufrière is the most surveyed botanical district for lichens. Keywords. Lichenology, Caribbean islands, tropical forest lichens, history of botany, Saint Lucia Saint Lucia is located at 14˚N and 61˚W in the Lesser had related that there were 693 collections by Imshaug from Antillean archipelago, which stretches from Anguilla in the Saint Lucia and that these specimens were catalogued online north to Grenada and Barbados in the south. The Caribbean (Johnson et al. 2005). An excursion was made by the authors Sea lies to the west and the Atlantic Ocean is to the east. The in April and May 2007 to collect and study lichens in Saint island has a land area of 616 km² (238 square miles). Lucia. The unpublished Imshaug field notebook referring to This paper presents a comprehensive checklist of lichens in the Saint Lucia expedition of 1963 was transcribed on a visit Saint Lucia, using new records, unpublished data, herbarium to MSC in September 2007. Loans of herbarium specimens specimens, online resources and published records. When were obtained for study from BG, MICH and MSC. These our study began in March 2007, Feuerer (2005) indicated 2 voucher specimens collected by Evans, Imshaug, Øvstedal species from Saint Lucia and Imshaug (1957) had reported 3 and the authors were examined with a stereoscope and a species. -

<I> Lecanoromycetes</I> of Lichenicolous Fungi Associated With

Persoonia 39, 2017: 91–117 ISSN (Online) 1878-9080 www.ingentaconnect.com/content/nhn/pimj RESEARCH ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.3767/persoonia.2017.39.05 Phylogenetic placement within Lecanoromycetes of lichenicolous fungi associated with Cladonia and some other genera R. Pino-Bodas1,2, M.P. Zhurbenko3, S. Stenroos1 Key words Abstract Though most of the lichenicolous fungi belong to the Ascomycetes, their phylogenetic placement based on molecular data is lacking for numerous species. In this study the phylogenetic placement of 19 species of cladoniicolous species lichenicolous fungi was determined using four loci (LSU rDNA, SSU rDNA, ITS rDNA and mtSSU). The phylogenetic Pilocarpaceae analyses revealed that the studied lichenicolous fungi are widespread across the phylogeny of Lecanoromycetes. Protothelenellaceae One species is placed in Acarosporales, Sarcogyne sphaerospora; five species in Dactylosporaceae, Dactylo Scutula cladoniicola spora ahtii, D. deminuta, D. glaucoides, D. parasitica and Dactylospora sp.; four species belong to Lecanorales, Stictidaceae Lichenosticta alcicorniaria, Epicladonia simplex, E. stenospora and Scutula epiblastematica. The genus Epicladonia Stictis cladoniae is polyphyletic and the type E. sandstedei belongs to Leotiomycetes. Phaeopyxis punctum and Bachmanniomyces uncialicola form a well supported clade in the Ostropomycetidae. Epigloea soleiformis is related to Arthrorhaphis and Anzina. Four species are placed in Ostropales, Corticifraga peltigerae, Cryptodiscus epicladonia, C. galaninae and C. cladoniicola -

Further Investigations on Rhizocarpon of North-Eastern Iran: R

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Journal of Mycology Volume 2014, Article ID 528041, 5 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/528041 Research Article Further Investigations on Rhizocarpon of North-Eastern Iran: R. geographicum Mahroo Haji Moniri Department of Biology, Faculty of Sciences, Islamic Azad University, Mashhad Branch, Mashhad 917 56 89 119, Iran Correspondence should be addressed to Mahroo Haji Moniri; h [email protected] Received 15 January 2014; Accepted 7 April 2014; Published 29 April 2014 Academic Editor: Simona Nardoni Copyright © 2014 Mahroo Haji Moniri. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Morphology, anatomy, secondary chemistry, ecology, and distribution of Rhizocarpon geographicum (Rhizocarpaceae, lichenized Ascomycota) in north-eastern Iran are investigated and discussed. 1. Introduction the elevation of the sites ranges from 1340 to 1880 m. Over 537 Rhizocarpon thalli were investigated of which 311 (58%) Iran has an exceptional variety of biomes which has resulted belong to R. geographicum. As a result much new information in an extensive diversity in many organism groups including became available on the species of Rhizocarpon [11–13]. Mor- lichens. The history of lichenological exploration in north- phological and anatomical characteristics of the thalli and eastern Iran is fairly extensive, dating back to the middle fruiting bodies were examined with a stereomicroscope and a of the twentieth century [1, 2]. Since 2004, however, the light microscope. Preparations were made in distilled water, investigations in the present Khorasan provinces have much 10% KOH and KI. -

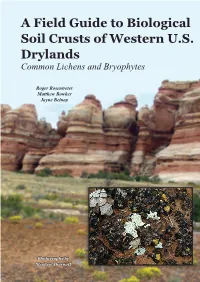

A Field Guide to Biological Soil Crusts of Western U.S. Drylands Common Lichens and Bryophytes

A Field Guide to Biological Soil Crusts of Western U.S. Drylands Common Lichens and Bryophytes Roger Rosentreter Matthew Bowker Jayne Belnap Photographs by Stephen Sharnoff Roger Rosentreter, Ph.D. Bureau of Land Management Idaho State Office 1387 S. Vinnell Way Boise, ID 83709 Matthew Bowker, Ph.D. Center for Environmental Science and Education Northern Arizona University Box 5694 Flagstaff, AZ 86011 Jayne Belnap, Ph.D. U.S. Geological Survey Southwest Biological Science Center Canyonlands Research Station 2290 S. West Resource Blvd. Moab, UT 84532 Design and layout by Tina M. Kister, U.S. Geological Survey, Canyonlands Research Station, 2290 S. West Resource Blvd., Moab, UT 84532 All photos, unless otherwise indicated, copyright © 2007 Stephen Sharnoff, Ste- phen Sharnoff Photography, 2709 10th St., Unit E, Berkeley, CA 94710-2608, www.sharnoffphotos.com/. Rosentreter, R., M. Bowker, and J. Belnap. 2007. A Field Guide to Biological Soil Crusts of Western U.S. Drylands. U.S. Government Printing Office, Denver, Colorado. Cover photos: Biological soil crust in Canyonlands National Park, Utah, cour- tesy of the U.S. Geological Survey. 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ....................................................................................... 4 How to use this guide .................................................................................... 4 Introduction ................................................................................................... 4 Crust composition .................................................................................. -

Symbiotic Microalgal Diversity Within Lichenicolous Lichens and Crustose

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Symbiotic microalgal diversity within lichenicolous lichens and crustose hosts on Iberian Peninsula gypsum biocrusts Patricia Moya 1*, Arantzazu Molins 1, Salvador Chiva 1, Joaquín Bastida 2 & Eva Barreno 1 This study analyses the interactions among crustose and lichenicolous lichens growing on gypsum biocrusts. The selected community was composed of Acarospora nodulosa, Acarospora placodiiformis, Diploschistes diacapsis, Rhizocarpon malenconianum and Diplotomma rivas-martinezii. These species represent an optimal system for investigating the strategies used to share phycobionts because Acarospora spp. are parasites of D. diacapsis during their frst growth stages, while in mature stages, they can develop independently. R. malenconianum is an obligate lichenicolous lichen on D. diacapsis, and D. rivas-martinezii occurs physically close to D. diacapsis. Microalgal diversity was studied by Sanger sequencing and 454-pyrosequencing of the nrITS region, and the microalgae were characterized ultrastructurally. Mycobionts were studied by performing phylogenetic analyses. Mineralogical and macro- and micro-element patterns were analysed to evaluate their infuence on the microalgal pool available in the substrate. The intrathalline coexistence of various microalgal lineages was confrmed in all mycobionts. D. diacapsis was confrmed as an algal donor, and the associated lichenicolous lichens acquired their phycobionts in two ways: maintenance of the hosts’ microalgae and algal switching. Fe and Sr were the most abundant microelements in the substrates but no signifcant relationship was found with the microalgal diversity. The range of associated phycobionts are infuenced by thallus morphology. Lichens are a well-known and reasonably well-studied examples of obligate fungal symbiosis 1,2. Tey have tra- ditionally been considered the symbiotic phenotype resulting from the interactions of a single fungal partner and one or a few photosynthetic partners.