Zombie Parsifal Kagen, Melissa the Opera Quarterly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

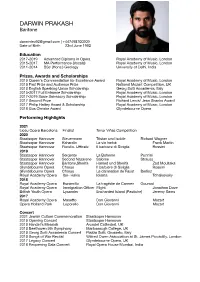

Darwin Prakash CV July 2021

DARWIN PRAKASH Baritone [email protected] | +447498700209 Date of Birth 23rd June 1993 Education 2017-2019 Advanced Diploma in Opera Royal Academy of Music, London 2015-2017 MA Performance (Vocals) Royal Academy of Music, London 2011-2014 BSc (Hons.) Geology University of Delhi, India Prizes, Awards and Scholarships 2019 Queen's Commendation for Excellence Award Royal Academy of Music, London 2019 First Prize and Audience Prize National Mozart Competition, UK 2018 English Speaking Union Scholarship Georg Solti Accademia, Italy 2015-2017 Full Entrance Scholarship Royal Academy of Music, London 2017-2019 Susie Sainsbury Scholarship Royal Academy of Music, London 2017 Second Prize Richard Lewis/ Jean Shanks Award 2017 Philip Hattey Award & Scholarship Royal Academy of Music, London 2016 Gus Christie Award Glyndebourne Opera Performing Highlights 2021 Liceu Opera Barcelona Finalist Tenor Viñas Competition 2020 Staatsoper Hannover Steuermann Tristan und Isolde Richard Wagner Staatsoper Hannover Kaherdin Le vin herbé Frank Martin Staatsoper Hannover Fiorello, Ufficale Il barbiere di Siviglia Rossini 2019 Staatsoper Hannover Sergente La Boheme Puccini Staatsoper Hannover Second Nazarene Salome Strauss Staatsoper Hannover Baritone,Sherifa Hamed und Sherifa Zad Moultaka Glyndebourne Opera Chorus Il barbiere di Siviglia Rossini Glyndebourne Opera Chorus La damnation de Faust Berlioz Royal Academy Opera Ibn- Hakia Iolanta Tchaikovsky 2018 Royal Academy Opera Escamillo La tragédie de Carmen Gounod Royal Academy Opera Immigration Officer Flight Jonathan Dove British Youth Opera Lysander Enchanted Island (Pastiche) Jeremy Sams 2017 Royal Academy Opera Masetto Don Giovanni Mozart Opera Holland Park Leporello Don Giovanni Mozart Concert 2021 Jewish Culture Commemoration Staatsoper Hannover 2019 Opening Concert Staatsoper Hannover 2019 Handel's Messiah Arundel Cathedral, UK 2018 Beethoven 9th Symphony Marlborough College, UK 2018 Georg Solti Accademia Concert Piazza Solti, Grosseto, Italy 2018 Songs of War Recital Wilfred Owen Association at St. -

Let Me Be Your Guide: 21St Century Choir Music in Flanders

Let me be your guide: 21st century choir music in Flanders Flanders has a rich tradition of choir music. But what about the 21st century? Meet the composers in this who's who. Alain De Ley Alain De Ley (° 1961) gained his first musical experience as a singer of the Antwerp Cathedral Choir, while he was still behind the school desks in the Sint-Jan Berchmans College in Antwerp. He got a taste for it and a few years later studied flute with Remy De Roeck and piano with Patrick De Hooghe, Freddy Van der Koelen, Hedwig Vanvaerenbergh and Urbain Boodts). In 1979 he continued his studies at the Royal Music Conservatory in Antwerp. Only later did he take private composition lessons with Alain Craens. Alain De Ley prefers to write music for choir and smaller ensembles. As the artistic director of the Flemish Radio Choir, he is familiar with the possibilities and limitations of a singing voice. Since 2003 Alain De Ley is composer in residence for Ensemble Polyfoon that premiered a great number of his compositions and recorded a CD dedicated to his music, conducted by Lieven Deroo He also received various commissions from choirs like Musa Horti and Amarylca, Kalliope and from the Flanders Festival. Alain De Ley’s music is mostly melodic, narrative, descriptive and reflective. Occasionally Alain De Ley combines the classical writing style with pop music. This is how the song Liquid Waltz was created in 2003 for choir, solo voice and pop group, sung by K’s Choice lead singer Sarah Bettens. He also regularly writes music for projects in which various art forms form a whole. -

Advance Program Notes New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players H.M.S

Advance Program Notes New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players H.M.S. Pinafore Friday, May 5, 2017, 7:30 PM These Advance Program Notes are provided online for our patrons who like to read about performances ahead of time. Printed programs will be provided to patrons at the performances. Programs are subject to change. Albert Bergeret, artistic director in H.M.S. Pinafore or The Lass that Loved a Sailor Libretto by Sir William S. Gilbert | Music by Sir Arthur Sullivan First performed at the Opera Comique, London, on May 25, 1878 Directed and conducted by Albert Bergeret Choreography by Bill Fabis Scenic design by Albère | Costume design by Gail Wofford Lighting design by Benjamin Weill Production Stage Manager: Emily C. Rolston* Assistant Stage Manager: Annette Dieli DRAMATIS PERSONAE The Rt. Hon. Sir Joseph Porter, K.C.B. (First Lord of the Admiralty) James Mills* Captain Corcoran (Commanding H.M.S. Pinafore) David Auxier* Ralph Rackstraw (Able Seaman) Daniel Greenwood* Dick Deadeye (Able Seaman) Louis Dall’Ava* Bill Bobstay (Boatswain’s Mate) David Wannen* Bob Becket (Carpenter’s Mate) Jason Whitfield Josephine (The Captain’s Daughter) Kate Bass* Cousin Hebe Victoria Devany* Little Buttercup (Mrs. Cripps, a Portsmouth Bumboat Woman) Angela Christine Smith* Sergeant of Marines Michael Connolly* ENSEMBLE OF SAILORS, FIRST LORD’S SISTERS, COUSINS, AND AUNTS Brooke Collins*, Michael Galante, Merrill Grant*, Andy Herr*, Sarah Hutchison*, Hannah Kurth*, Lance Olds*, Jennifer Piacenti*, Chris-Ian Sanchez*, Cameron Smith, Sarah Caldwell Smith*, Laura Sudduth*, and Matthew Wages* Scene: Quarterdeck of H.M.S. Pinafore *The actors and stage managers employed in this production are members of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of Professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. -

Trix/Minitrix New Items 2017 Brochure HERE

New Items 2017 Trix. The Fascination of the Original. New Items 2017 E E © Gebr. Märklin & Cie. GmbH – All rights reserved. © Gebr. Märklin & Cie. GmbH – All rights reserved. Dear Trix Fans, Welcome to the New Year for 2017! This year we are again presenting our new items brochure with many impressive models for Minitrix, Trix H0, and Trix Express. Through all of the eras, the railroad has provided transporta- tion for business and industry. It has also left its mark on the life of entire cities and regions over many generations. It is thus no wonder that we have given special importance to freight service as models. This year we are spreading the entire range across model railroad rails. Regardless of whether it is the impressive class 42 steam locomotive of the Fifties or the latest variations of the Vectron as the TRAXX family. We are bringing impressive, prototypical trains/train New Items for MiniTrix 2017 2 – 55 New Items for Trix H0 2017 56 – 105 runs to your model railroad scenery with car sets in all eras, some of them with new tooling. However, 2017 is also the year of the “TransEuropExpress”, which seven railroads started exactly 60 years ago with the ambitious plan to bring elegant, comfortable traveling to the rails. Come with us to explore this concept through the eras New Items for Trix Express 2017 106–109 of the history of long-distance passenger service. Now, give free rein to your personal operating and collector passion and discover your favorites on the following pages. Fulfill your wishes – your local specialty dealer is waiting for your visit! MiniTrix Club Model for 2017 6– 7 MHI Exclusiv 1/2017 4 – 8 Your Trix Team wishes you much fun exploring the new items H0 Trix Club Model for 2017 58 – 59 Museumcars 117 for 2017! Trix Club 110 Reparatur-Service 118 Registration Form 113 General References 118 Trix Club Cars for 2017 111 Important Service Information 118 Trix Club Anniversary Car 112 Explanation of Symbols 119 Index to the Item Numbers 120 1 © Gebr. -

2015-2016 Lynn University Wind Ensemble-Wind Works Wit'wit

Lynn Wind Ensemble Wind Works wit' Wit LYNN Conservatory of Music Wind Ensemble Roster FLUTE T' anna Tercero Jared Harrison Hugo Valverde Villalobos Scott Kemsley Robert Williams Al la Sorokoletova TRUMPET OBOE Zachary Brown Paul Chinen Kevin Karabell Walker Harnden Mark Poljak Trevor Mansell Alexander Ramazanov John Weisberg Luke Schwalbach Natalie Smith CLARINET Tsukasa Cherkaoui TROMBONE Jacqueline Gillette Mariana Cisneros Cameron Hewes Halgrimur Hauksson Christine Pascual-Fernandez Zongxi Li Shaquille Southwell Em ily Nichols Isabel Thompson Amalie Wyrick-Flax EUPHONIUM Brian Logan BASSOON Ryan Ruark Sebastian Castellanos Michael Pittman TUBA Sodienye Fi nebone ALTO SAX Joseph Guimaraes Matthew Amedio Dannel Espinoza PERCUSSION Isaac Fernandez Hernandez TENOR SAX Tyler Flynt Kyle Mechmet Juanmanuel Lopez Bernadette Manalo BARITONE SAX Michael Sawzin DOUBLE BASS August Berger FRENCH HORN Mileidy Gonzalez PIANO Shaun Murray Al fonso Hernandez Please silence or turn off all electronic devices, including cell phones, beepers, and watch alarms. Unauthorized recording or photography is strictly prohibited Lynn Wind Ensemble Kenneth Amis, music director and conductor 7:30 pm, Friday, January 15, 2016 Keith C. and Elaine Johnson Wold Performing Arts Center Onze Variations sur un theme de Haydn Jean Fran c;; aix lntroduzione - Thema (1912-1997) Variation 1: Pochissimo piu vivo Variation 2: Moderato Variation 3: Allegro Variation 4: Adagio Variation 5: Mouvement de va/se viennoise Variation 6: Andante Variation 7: Vivace Variation 8: Mouvement de valse Variation 9: Moderato Variation 10: Mo/to tranquil/a Variation 11 : Allegro giocoso Circus Polka Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) Hommage a Stravinsky Ole Schmidt I. (1928-2010) II. Ill. Spiel, Op.39 Ernst Toch /. -

Marschner Heinrich

MARSCHNER HEINRICH Compositore tedesco (Zittau, 16 agosto 1795 – Hannover, 16 dicembre 1861) 1 Annoverato fra i maggiori compositori europei della sua epoca, nonché degno rivale in campo operistico di Carl Maria von Weber, strinse amicizia con i maggiori musicisti del tempo, fra cui Ludwig van Beethoven e Felix Mendelssohn Bartoldy. Dopo gli studi fatti a Lipsia ed a Praga con Tomášek e dopo essersi introdotto nel mondo musicale viennese, fu nominato maestro di cappella a Bratislava e successivamente divenne il direttore dei teatri dell'opera di Dresda e Lipsia; fu quindi ad Hannover nel periodo 1830-59, per dirigere la cappella di corte. Marschner fu fondamentalmente un compositore teatrale, fra le opere che gli conferirono maggior fama si annoverano: Der Vampyr (1828), Der templar und die Jüdin (1829) e un'opera di gusto popolare e leggendario, come è nel suo stile, intitolata Hans Heiling (1833), la quale ha alcune analogie con L'olandese volante di Richard Wagner. Caratteristica dell'arte di Marschner sono: la ricerca (nel melodramma) di soggetti soprannaturali caratteristici di quel senso puramente romantico di "orrore dilettevole", ma anche cavallereschi e soprattutto popolari, resi attraverso una ritmica incalzante, una vasta coloritura dei timbri orchestrali e con l'ausilio di numerosi leitmotiv e fili conduttori musicali. Non mancano inoltre nella sua produzione numerosi Lieder, due quartetti per pianoforte e ben sette trii per pianoforte particolarmente apprezzati da Robert Schumann. 2 3 HANS HEILING Tipo: Opera romantica in un prologo e tre atti Soggetto: libretto di Philipp Eduard Devrient Prima: Berlino, Königliches Opernhaus, 24 maggio 1833 Cast: la regina degli spiriti (S), Hans Heiling (Bar), Anna (S), Gertrude (A), Konrad (T), Stephan (B), Niklas (rec); spiriti, contadini, invitati, giocatori, tiratori Autore: Heinrich Marschner (1795-1861) Il personaggio di Hans Heiling, tra quelli creati da Marschner, rappresenta una delle più notevoli incarnazioni del tipico tema romantico dell’io diviso, condannato a non trovare la propria unità. -

DANSES CQNCERTANTES by IGOR STRAVINSKY: an ARRANGEMENT for TWO PIANOS, FOUR HANDS by KEVIN PURRONE, B.M., M.M

DANSES CQNCERTANTES BY IGOR STRAVINSKY: AN ARRANGEMENT FOR TWO PIANOS, FOUR HANDS by KEVIN PURRONE, B.M., M.M. A DISSERTATION IN FINE ARTS Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Accepted August, 1994 t ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to extend my appreciation to Dr. William Westney, not only for the excellent advice he offered during the course of this project, but also for the fine example he set as an artist, scholar and teacher during my years at Texas Tech University. The others on my dissertation committee-Dr. Wayne Hobbs, director of the School of Music, Dr. Kenneth Davis, Dr. Richard Weaver and Dr. Daniel Nathan-were all very helpful in inspiring me to complete this work. Ms. Barbi Dickensheet at the graduate school gave me much positive assistance in the final preparation and layout of the text. My father, Mr. Savino Purrone, as well as my family, were always very supportive. European American Music granted me permission to reprint my arrangement—this was essential, and I am thankful for their help and especially for Ms. Caroline Kane's assistance in this matter. Many other individuals assisted me, sometimes without knowing it. To all I express my heartfelt thanks and appreciation. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ii CHAPTER L INTRODUCTION 1 n. GENERAL PRINCIPLES 3 Doubled Notes 3 Articulations 4 Melodic Material 4 Equal Roles 4 Free Redistribution of Parts 5 Practical Considerations 5 Homogeneity of Rhythm 5 Dynamics 6 Tutti GesUires 6 Homogeneity of Texmre 6 Forte-Piano Chords 7 Movement EI: Variation I 7 Conclusion 8 BIBLIOGRAPHY 9 m APPENDIX A. -

Der Vampyr De Heinrich Marschner

DESCUBRIMIENTOS Der Vampyr de Heinrich Marschner por Carlos Fuentes y Espinosa ay momentos extraordinarios Polidori creó ahí su obra más famosa y trascendente, pues introdujo en un breve cuento de en la historia de la Humanidad horror gótico, por vez primera, una concreción significativa de las creencias folclóricas sobre que, con todo gusto, el vampirismo, dibujando así el prototipo de la concepción que se ha tenido del monstruo uno querría contemplar, desde entonces, al que glorias de la narrativa fantástica como E.T.A. Hoffmann, Edgar Allan dada la importancia de la Poe, Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu, Jules Verne y el ineludible Abraham Stoker aprovecharían y Hproducción que en ellos se generara. ampliarían magistralmente. Sin duda, un momento especial para la literatura fantástica fue aquella reunión En su relato, Polidori presenta al vampiro, Lord Ruthven, como un antihéroe integrado, a de espléndidos escritores en Ginebra, su manera, a la sociedad, y no es difícil identificar la descripción de Lord Byron en él (sin Suiza, a mediados de junio de 1816 (el mencionar que con ese nombre ya una escritora amante de Byron, Caroline Lamb, nombraba “año sin verano”), cuando en la residencia como Lord Ruthven un personaje con las características del escritor). Precisamente por del célebre George Gordon, Lord Byron, eso, por la publicación anónima original, por la notoria emulación de las obras de Byron y a orillas del lago Lemán, departieron el su fama, las primeras ediciones del cuento se atribuyeron a él, aunque con el tiempo y una baronet Percy Bysshe Shelley, notable incómoda cantidad de disputas, terminara por dársele el crédito al verdadero escritor, que poeta y escritor, su futura esposa Mary fuera tío del poeta y pintor inglés Dante Gabriel Rossetti. -

110308-10 Bk Lohengrineu 13/01/2005 03:29Pm Page 12

110308-10 bk LohengrinEU 13/01/2005 03:29pm Page 12 her in his arms, reproaching her for bringing their @ Ortrud comes forward, declaring the swan to be happiness to an end. She begs him to stay, to witness her Elsa’s brother, the heir to Brabant, whom she had repentance, but he is adamant. The men urge him to bewitched with the help of her own pagan gods. WAGNER stay, to lead them into battle, but in vain. He promises, Lohengrin kneels in prayer, and when the white dove of however, that Germany will be victorious, never to be the Holy Grail appears, he unties the swan. As it sinks defeated by the hordes from the East. Shouts announce down, Gottfried emerges. Ortrud sinks down, with a the appearance of the swan. cry, while Gottfried bows to the king and greets Elsa. Lohengrin Lohengrin leaps quickly into the boat, which is drawn ! Lohengrin greets the swan. Sorrowfully he turns away by the white dove. Elsa sees him, as he makes his towards it, telling Elsa that her brother is still alive, and sad departure. She faints into her brother’s arms, as the G WIN would have returned to her a year later. He leaves his knight disappears, sailing away into the distance. AN DG horn, sword, and ring for Gottfried, kisses Elsa, and G A F SS moves towards the boat. L E Keith Anderson O N W Mark Obert-Thorn Mark Obert-Thorn is one of the world’s most respected transfer artist/engineers. He has worked for a number of specialist labels, including Pearl, Biddulph, Romophone and Music & Arts. -

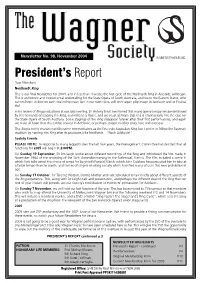

Wagner Oct 04.Indd

Wagner Society in NSW Inc. Newsletter No. 98, November 2004 IN NEW SOUTH WALES INC. President’s Report Dear Members Neidhardt Ring This is our final Newsletter for 2004, and in less than 4 weeks the first cycle of the Neidhardt Ring in Adelaide will begin. This is an historic and monumental undertaking for the State Opera of South Australia, and we in the Eastern States, who cannot hope to dine on such exalted operatic fare in our own cities, will once again pilgrimage to Adelaide and its Festival Hall. In his review of Ring productions at our July meeting, Dr Antony Ernst mentioned that many opera companies are destroyed by the demands of staging the Ring, as moths to a flame, and we must all hope that this is emphatically not the case for the State Opera of South Australia. Some stagings of the Ring disappear forever after their first performances, and again we must all hope that this can be revived in Adelaide, or perhaps staged in other cities here and overseas. This Ring is being characterised by some commentators as the first truly Australian Ring, but I prefer to follow the Bayreuth tradition by naming this Ring after its producer, Elke Neidhardt. “Nach Adelaide!” Society Events PLEASE NOTE: In response to many requests over the last few years, the Management Committee has decided that all functions for 2005 will begin at 2:00PM. On Sunday 19 September, Dr Jim Leigh spoke about different recordings of the Ring and introduced the film made in November 1964 of the recording of the Solti Gotterdammerung in the Sofiensaal, Vienna. -

Monatsspielplan September 2021

22 / Semperoper Dresden Saison 2021 Spielplan - bonnent*innen bonnent*innen A über die geltenden über die geltenden GSBESUCH N ellu T S ageskasse, die telefonische Erreichbarkeit ageskasse, die telefonische Erreichbarkeit T N VOR N E E R H ON I bo-Service befinden sich in der Schinkelwache am bo-Service befinden sich in der Schinkelwache am ÜR I A F R heatergastronomie in der Semperoper Dresden in der Semperoper heatergastronomie E T ORMAT WEISE ROP F N E I andemie entnehmen Sie bitte unserer Website auf semperoper.de. auf semperoper.de. Website andemie entnehmen Sie bitte unserer N P H MP E R S bendkasse der Semperoper öffnet jeweils 1 Stunde vor bendkasse der Semperoper bendkasse in Semper Zwei öffnet jeweils ½ Stunde vor ageskasse und der VICEI UELLE A T A R DE T ufgrund der aktuellen, dynamischen Situation ändern sich diese 0351 4911 706 ∙ [email protected] ∙ semperoper.de 0351 4911 706 ∙ [email protected] heaterplatz. heaterplatz 2 0351 4911 705 ∙ F 700 [email protected] 0351 320 73 60 ∙ F 611 semperoper-erleben.de 0351 44 00 88 ∙ F 22 N semperoper.de ABO-SERVICE* T *Die aktuellen Öffnungszeiten der Informationen zu den Kartenverkaufster des Besucherservice und alle weiteren während minen, Buchungsbedingungen sowie den geltenden Hygieneregeln der Corona- ABENDKASSE Die SE Die T TAGESKASSE* Dresden Semperoper und Service Vertrieb T 01067 Dresden TICKETS T Vorstellungsbeginn. Die Vorstellungsbeginn. ERLEBEN – FÜHRUNGEN UND SHOP SEMPEROPER T ∙ [email protected] [email protected] DRESDEN IN DER SEMPEROPER GASTRONOMIE Stefan Hermann – T ∙ gastronomie-semperoper.de [email protected] im September 2021: Die für die Vorstellungen Verkaufsbeginn Karten beginnt der restlichen Verkauf Der freie erhalten eine Vorkaufsoption. -

The Music of Three Dublin Musical Societies of the Late Eighteenth And

L ,0 . L \\(o l> NUI MAYNOOTH 011scoi 1 na h£ireann M3 Nuad The music of three Dublin musical societies of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries: The Anacreontic Society, The Antient Concerts Society and The Sons of Handel. A descriptive catalogue. Catherine Mary Pia Kiely-Ferris Volume I of IV: The Anacreontic Society Main Catalogue Thesis submitted to National University of Ireland, Maynooth for the Degree of Master of Literature in Music. Head of Department: Professor Gerard Gillen Music Department National University of Ireland, Maynooth Maynooth Co. Kildare Supervisor: Dr Barra Boydell Music Department National University of Ireland, Maynooth Maynooth Co. Kildare July 2005 LIST OF VOLUMES 1. The Anacreontic Society Main Catalogue 2. The Anacreontic Society Bound Sets Catalogue 3. The Sons of Handel Catalogue and The Antient Concerts Society Catalogue 4. The Antient Concerts Society Bound Sets Catalogue TABLE OF CONTENTS Volume I of TV List of volumes...............................................................................................i Table of contents.......................................................................................... ii Preface.......................................................................................................... iii I: Introduction.........................................................................................1 2: Cataloguing procedures and user guide............................................ 8 3: The Anacreontic Society Main Catalogue.....................................