Final Research Report MA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Militarized Youths in Western Côte D'ivoire

Militarized youths in Western Côte d’Ivoire - Local processes of mobilization, demobilization, and related humanitarian interventions (2002-2007) Magali Chelpi-den Hamer To cite this version: Magali Chelpi-den Hamer. Militarized youths in Western Côte d’Ivoire - Local processes of mobiliza- tion, demobilization, and related humanitarian interventions (2002-2007). African Studies Centre, 36, 2011, African Studies Collection. hal-01649241 HAL Id: hal-01649241 https://hal-amu.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01649241 Submitted on 27 Nov 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. African Studies Centre African Studies Collection, Vol. 36 Militarized youths in Western Côte d’Ivoire Local processes of mobilization, demobilization, and related humanitarian interventions (2002-2007) Magali Chelpi-den Hamer Published by: African Studies Centre P.O. Box 9555 2300 RB Leiden The Netherlands [email protected] www.ascleiden.nl Cover design: Heike Slingerland Cover photo: ‘Market scene, Man’ (December 2007) Photographs: Magali Chelpi-den Hamer Printed by Ipskamp -

Mathematics in African History and Cultures

Paulus Gerdes & Ahmed Djebbar MATHEMATICS IN AFRICAN HISTORY AND CULTURES: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY African Mathematical Union Commission on the History of Mathematics in Africa (AMUCHMA) Mathematics in African History and Cultures Second edition, 2007 First edition: African Mathematical Union, Cape Town, South Africa, 2004 ISBN: 978-1-4303-1537-7 Published by Lulu. Copyright © 2007 by Paulus Gerdes & Ahmed Djebbar Authors Paulus Gerdes Research Centre for Mathematics, Culture and Education, C.P. 915, Maputo, Mozambique E-mail: [email protected] Ahmed Djebbar Département de mathématiques, Bt. M 2, Université de Lille 1, 59655 Villeneuve D’Asq Cedex, France E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Cover design inspired by a pattern on a mat woven in the 19th century by a Yombe woman from the Lower Congo area (Cf. GER-04b, p. 96). 2 Table of contents page Preface by the President of the African 7 Mathematical Union (Prof. Jan Persens) Introduction 9 Introduction to the new edition 14 Bibliography A 15 B 43 C 65 D 77 E 105 F 115 G 121 H 162 I 173 J 179 K 182 L 194 M 207 N 223 O 228 P 234 R 241 S 252 T 274 U 281 V 283 3 Mathematics in African History and Cultures page W 290 Y 296 Z 298 Appendices 1 On mathematicians of African descent / 307 Diaspora 2 Publications by Africans on the History of 313 Mathematics outside Africa (including reviews of these publications) 3 On Time-reckoning and Astronomy in 317 African History and Cultures 4 String figures in Africa 338 5 Examples of other Mathematical Books and 343 -

OUT of AFRICA: Byting Down on Wildlife Cybercrime CONTENTS

OUT OF AFRICA: Byting Down on Wildlife Cybercrime CONTENTS 1 | EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 2 | BACKGROUND 4 3 | RESEARCHING ONLINE WILDLIFE TRADE IN AFRICA 5 4 | KEY RESULTS AT A GLANCE 7 5 | METHODOLOGY 9 6 | CITES AND WILDLIFE CYBERCRIME 10 7 | OUR PARTNERS 11 8 | INTERNET USE IN AFRICA 13 9 | SUMMARY RESULTS 14 10 | RESULTS BY COUNTRY 19 SOUTH AFRICA • NIGERIA • IVORY COAST • KENYA • TANZANIA • UGANDA • ETHIOPIA 11 | CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 29 1 | EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) This research is part of a broader project to has been researching the threat that online wildlife address wildlife cybercrime in Africa, funded by the trade poses to endangered species since 2004. During US government’s Department of State’s Bureau of that time, our research in over 25 countries around International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs the globe has revealed the vast scale of trade in wildlife (INL). The wider project included researching trade in and their parts and products on the world’s largest elephant, rhino and tiger products over the 'Darknet'; marketplace, the Internet - a market that is open for providing training on investigating wildlife cybercrime business 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. to enforcers in South Africa and Kenya; ensuring policy Whilst legal trade exists in respect of many species makers addressed the threat of wildlife cybercrime of wildlife, online platforms can provide easy opportunities through adopting Decision 17.92 entitled Combatting for criminal activities. Trade over the Internet is often Wildlife Cybercrime at the CoP17 of the Convention largely unregulated and anonymous, often with little to on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild no monitoring or enforcement action being taken against Fauna and Flora (CITES) in Johannesburg 2016; carrying wildlife cybercriminals. -

Étude Originale

Étude originale Distribution des espèces de Striga et infestation des cultures céréalières dans le nord de la Côte d'Ivoire Charles Konan Kouakou1,2 2 Résumé Louise Akanvou Les cultures ce´re´alie`res sont pour la plupart infeste´es par des espe`ces de Striga dans le nord 1 Irie Arsène Zoro Bi de la Coˆte d’Ivoire. Dans cette e´tude, les espe`ces de Striga, leur re´partition, abondance et 2 Rene Akanvou intensite´ d’infestation ont e´te´ de´termine´es. Les surfaces de ce´re´ales infeste´es ont e´te´ 1,2 Hugues Annicet N'da estime´es. Les donne´es ont e´te´ collecte´es a` travers des enqueˆtes extensives et intensives. 1 Universite Nangui Abrogoua Des e´chantillonnages ont e´te´ re´alise´s dans des champs cultive´s. Selon la carte des zones Unite de formation et de recherche d’infestation de Striga actualise´e, les zones infeste´es couvrent le nord du pays de 8˚47,17’ a` des sciences de la nature 10˚38,84’ de latitude nord et de 2˚47,68’ a` 7˚55,20’ de longitude ouest. La zone infeste´e 02 BP 801 occupe une superficie cultivable de 3 191 850 ha. Un total de 71,8 % des villages situe´s Abidjan 02 dans cette zone sont infeste´s par Striga spp. L’hypothe`se d’e´volution des infestations Côte d'Ivoire suivant un gradient nord-sud a e´te´ confirme´e. Les infestations ont commence´ en zone de <[email protected]> <[email protected]> savane soudanienne et ont atteint la moitie´ de la zone de savane sub-soudanienne. -

Variable Name: Identity

Data Codebook for Round 6 Afrobarometer Survey Prepared by: Thomas A. Isbell University of Cape Town January 2017 University of Cape Town (UCT) Center for Democratic Development (CDD-Ghana) Michigan State University (MSU) Centre for Social Science Research 14 W. Airport Residential Area Department of Political Science Private Bag, Rondebosch, 7701, South Africa P.O. Box 404, Legon-Accra, Ghana East Lansing, Michigan 48824 27 21 650 3827•fax: 27 21 650 4657 233 21 776 142•fax: 233 21 763 028 517 353 3377•fax: 517 432 1091 Mattes ([email protected]) Gyimah-Boadi ([email protected]) Bratton ([email protected]) Copyright Afrobarometer Table of Contents Page number Variable descriptives 3-72 Appendix 1: Sample characteristics 73 Appendix 2: List of country abbreviations and country-specific codes 74 Appendix 3: Technical Information Forms for each country survey 75-111 Copyright Afrobarometer 2 Question Number: COUNTRY Question: Country Variable Label: Country Values: 1-36 Value Labels: 1=Algeria, 2=Benin, 3=Botswana, 4=Burkina Faso, 5=Burundi, 6=Cameroon, 7=Cape Verde, 8=Cote d'Ivoire, 9=Egypt, 10=Gabon, 11=Ghana, 12=Guinea, 13=Kenya, 14=Lesotho, 15=Liberia, 16=Madagascar, 17=Malawi, 18=Mali, 19=Mauritius, 20=Morocco, 21=Mozambique, 22=Namibia, 23=Niger, 24=Nigeria, 25=São Tomé and Príncipe, 26=Senegal, 27=Sierra Leone, 28=South Africa, 29=Sudan, 30=Swaziland, 31=Tanzania, 32=Togo, 33=Tunisia, 34=Uganda, 35=Zambia, 36=Zimbabwe Note: Answered by interviewer Question Number: COUNTRY_R5List Question: Country Variable Label: Country in R5 Alphabetical -

Côte D'ivoire Country Focus

European Asylum Support Office Côte d’Ivoire Country Focus Country of Origin Information Report June 2019 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office Côte d’Ivoire Country Focus Country of Origin Information Report June 2019 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9476-993-0 doi: 10.2847/055205 © European Asylum Support Office (EASO) 2019 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © Mariam Dembélé, Abidjan (December 2016) CÔTE D’IVOIRE: COUNTRY FOCUS - EASO COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT — 3 Acknowledgements EASO acknowledges as the co-drafters of this report: Italy, Ministry of the Interior, National Commission for the Right of Asylum, International and EU Affairs, COI unit Switzerland, State Secretariat for Migration (SEM), Division Analysis The following departments reviewed this report, together with EASO: France, Office Français de Protection des Réfugiés et Apatrides (OFPRA), Division de l'Information, de la Documentation et des Recherches (DIDR) Norway, Landinfo The Netherlands, Immigration and Naturalisation Service, Office for Country of Origin Information and Language Analysis (OCILA) Dr Marie Miran-Guyon, Lecturer at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS), researcher, and author of numerous publications on the country reviewed this report. It must be noted that the review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. -

The SAT-3/WASC Cable Ghana Case Study Eric Osiakwan1

The Case for “Open Access” Communications Infrastructure in Africa: The SAT-3/WASC cable Ghana case study Eric Osiakwan1 ASSOCIATION FOR PROGRESSIVE COMMUNICATIONS (APC) APC-200805-CIPP-R-EN-PDF-0047 ISBN 92-95049-49-7 COMMISSIONED BY THE ASSOCIATION FOR PROGRESSIVE COMMUNICATIONS (APC) CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION-NONCOMMERCIAL-SHAREALIKE 3.0 LICENCE GRAPHICS: COURTESY OF AUTHOR 1Eric Osiakwan is an ICT specialist with extensive experience in the African internet market. He is Executive Secretary of the African Internet Service Providers Association and the Ghana Internet Service Providers Association, and consults on ICT developments in Africa. Table of Contents 1 Overview of report.............................................................................................. 3 2 Background .......................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Brief country profile..................................................................................... 4 2.2 Overview of Ghana’s telecommunications market................................. 5 2.3 History of the SAT-3/WASC cable in Ghana .......................................... 9 2.4 The impact of SAT-3/WASC in Ghana................................................... 12 3 Performance indicators – successes and failures.......................................... 14 3.1 Subscription, usage and capacity utilisation.......................................... 14 3.2 Cost and tariffs........................................................................................... -

Engineering Change – Towards a Sustainable Future in the Developing

Engineering Change Towards a sustainable future in the developing world Edited by Peter Guthrie, Calestous Juma and Hayaatun Sillem Engineering Change Towards a sustainable future in the developing world Edited by: Professor Peter Guthrie OBE FREng Professor of Engineering for Sustainable Development Centre for Sustainable Development Department of Engineering, University of Cambridge Professor Calestous Juma HonFREng FRS Professor of the Practice of International Development Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University Dr Hayaatun Sillem International Manager The Royal Academy of Engineering Consultant editor: Ian Jones, Director, Isinglass Consultancy Ltd Published: October 2008 ISBN No: 1-903496-41-1 Engineering Change Towards a sustainable future in the developing world Table of Contents Foreword 3 Engineering a better world 5 Calestous Juma Profile: Rajendra K Pachauri 11 Engineering growth: Technology, innovation and policy making in Rwanda 13 Romain Murenzi and Mike Hughes Water and waste: Engineering solutions that work 21 Sandy Cairncross Globalising innovation: Engineers and innovation in a networked world 25 Gordon Conway Profile: Dato Lee Yee-Cheong 32 Engineering, wealth creation and disaster recovery: The case of Afghanistan 35 M Masoom Stanekzai and Heather Cruickshank Untapped potential: The role of women engineers in African development 41 Joanna Maduka Scarce skills or skills gaps: Assessing needs and developing solutions 47 Allyson Lawless Profile: Irenilza de Alencar -

AFRICA AGRICULTURE STATUS REPORT 2017 the Business of Smallholder Agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa

AFRICA AGRICULTURE STATUS REPORT 2017 The Business of Smallholder Agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa AFRICA AGRICULTURE STATUS REPORT 2017 01 Africa Agriculture Status Report 2017 THE BUSINESS OF SMALLHOLDER AGRICULTURE IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA Copyright @2017 by the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA) All rights reserved. The publisher encourages fair use of this material provided proper citation is made. ISSN: 2313-5387 Correct Citation: AGRA. (2017). Africa Agriculture Status Report: The Business of Smallholder Agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa (Issue 5). Nairobi, Kenya: Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA). Issue No. 5 Managing Editor: Daudi Sumba, (AGRA) Project Coordinator: Jane Njuguna (AGRA) Editor: Anne Marie Nyamu, Editorial, Publishing and Training Consultant Data Table Coordinators: Jane Njuguna, Josephine Njau, Alice Thuita (AGRA) Design and Layout: Kristina Just Cover Concept: Communication Unit AGRA Cover Photos: Shutterstock, AGRA, Ecomedia Printing: Ecomedia AGRA wishes to acknowledge the following contributing institutions: The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the policies or position of Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA) or its employees. Although AGRA has made every effort to ensure accuracy and completeness of information entered in this book, we assume no responsibilities for errors, inaccuracies, omissions or inconsistencies included herein. The mention of specific companies, manufacturers or their products, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply endorsement or recommendation or approval by AGRA in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The descriptions, charts and maps used do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of AGRA concerning the development, legal or constitutional status of any country. -

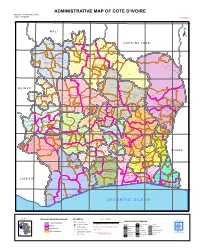

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP of COTE D'ivoire Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'ivoire 2Nd Edition

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP OF COTE D'IVOIRE Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'IVOIRE 2nd Edition 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W 11°0'0"N 11°0'0"N M A L I Papara Débété ! !. Zanasso ! Diamankani ! TENGRELA [! ± San Koronani Kimbirila-Nord ! Toumoukoro Kanakono ! ! ! ! ! !. Ouelli Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona ! ! Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko ! ! B U R K I N A F A S O !. Kouban Bougou ! Blésségué ! Sokoro ! Niéllé Tahara Tiogo !. ! ! Katogo Mahalé ! ! ! Solognougo Ouara Diawala Tienny ! Tiorotiérié ! ! !. Kaouara Sananférédougou ! ! Sanhala Sandrégué Nambingué Goulia ! ! ! 10°0'0"N Tindara Minigan !. ! Kaloa !. ! M'Bengué N'dénou !. ! Ouangolodougou 10°0'0"N !. ! Tounvré Baya Fengolo ! ! Poungbé !. Kouto ! Samantiguila Kaniasso Monogo Nakélé ! ! Mamougoula ! !. !. ! Manadoun Kouroumba !.Gbon !.Kasséré Katiali ! ! ! !. Banankoro ! Landiougou Pitiengomon Doropo Dabadougou-Mafélé !. Kolia ! Tougbo Gogo ! Kimbirila Sud Nambonkaha ! ! ! ! Dembasso ! Tiasso DENGUELE REGION ! Samango ! SAVANES REGION ! ! Danoa Ngoloblasso Fononvogo ! Siansoba Taoura ! SODEFEL Varalé ! Nganon ! ! ! Madiani Niofouin Niofouin Gbéléban !. !. Village A Nyamoin !. Dabadougou Sinémentiali ! FERKESSEDOUGOU Téhini ! ! Koni ! Lafokpokaha !. Angai Tiémé ! ! [! Ouango-Fitini ! Lataha !. Village B ! !. Bodonon ! ! Seydougou ODIENNE BOUNDIALI Ponondougou Nangakaha ! ! Sokoro 1 Kokoun [! ! ! M'bengué-Bougou !. ! Séguétiélé ! Nangoukaha Balékaha /" Siempurgo ! ! Village C !. ! ! Koumbala Lingoho ! Bouko Koumbolokoro Nazinékaha Kounzié ! ! KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Togoniéré ! Sirana -

2014, Une Année Pleine De Promesses Tenues

BULLETIN D’INFORMATIONS GENERALES DU GOUVERNEMENT DE CÔTE D’IVOIRE N°86 - Mars 2015 [email protected] CONFÉRENCERELANCE ÉCONOMIQUE INTERNATIONale ET COHÉSION sur l’eMERGENce SOCIALE de l’AFRIQUE Les2014, dix unepoints année de la pleinevision de l’émergence dude Présidentpromesses Alassane tenues Ouattara pour la Côte d’Ivoire INVITÉ DU MOIS INAUGURATION ZOOM SUR Ministre auprès du Président de la République, chargé de la Défense Station d’eau potable de Bonoua Haute Autorité pour la Bonne Gouvernance SOMMAIRE 3 EDITORIAL 4 AU JOUR LE JOUR 4 Lutte contre Ebola : Une feuille de route proposée à la Côte d’Ivoire 5 Nutrition : Une stratégie pour promouvoir les bonnes pratiques nutritionnelles élaborée 6 Code électoral : Une quinzaine d’articles à modifier 7 Grandes Chancelleries d’Afrique Francophone : La 7ème conférence s’est tenue à Abidjan 7 Aéroport FHB : Le ministre des Transports fait des précisions 8 Conférence sur le cacao : Les pays producteurs ont élaboré des stratégies nationales conformes à la demande 9 Rendez-vous du Gouvernement : L’armature institutionnelle, professionnelle et sociale de l’armée s’est renforcée 10 EN LIGNE DE MIRE 4 11 Jacqueville : Inauguration du Pont Philippe Grégoire Yacé 11 Eau potable : La station d’eau de Bonoua opérationnelle 12 Réconciliation : Création de la Commission Nationale pour la Réconciliation et l’Indemnisation des Victimes 14 Présidence : Helen Clark et Makhtar Diop discutent de développement avec le Chef de l’Etat 15 Visite d’Etat dans le District du Bas-Sassandra : 3700 milliards FCFA -

See Full Prospectus

G20 COMPACT WITHAFRICA CÔTE D’IVOIRE Investment Opportunities G20 Compact with Africa 8°W To 7°W 6°W 5°W 4°W 3°W Bamako To MALI Sikasso CÔTE D'IVOIRE COUNTRY CONTEXT Tengrel BURKINA To Bobo Dioulasso FASO To Kampti Minignan Folon CITIES AND TOWNS 10°N é 10°N Bagoué o g DISTRICT CAPITALS a SAVANES B DENGUÉLÉ To REGION CAPITALS Batie Odienné Boundiali Ferkessedougou NATIONAL CAPITAL Korhogo K RIVERS Kabadougou o —growth m Macroeconomic stability B Poro Tchologo Bouna To o o u é MAIN ROADS Beyla To c Bounkani Bole n RAILROADS a 9°N l 9°N averaging 9% over past five years, low B a m DISTRICT BOUNDARIES a d n ZANZAN S a AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT and stable inflation, contained fiscal a B N GUINEA s Hambol s WOROBA BOUNDARIES z a i n Worodougou d M r a Dabakala Bafing a Bere REGION BOUNDARIES r deficit; sustainable debt Touba a o u VALLEE DU BANDAMA é INTERNATIONAL BOUNDARIES Séguéla Mankono Katiola Bondoukou 8°N 8°N Gontougo To To Tanda Wenchi Nzerekore Biankouma Béoumi Bouaké Tonkpi Lac de Gbêke Business friendly investment Mont Nimba Haut-Sassandra Kossou Sakassou M'Bahiakro (1,752 m) Man Vavoua Zuenoula Iffou MONTAGNES To Danane SASSANDRA- Sunyani Guemon Tiebissou Belier Agnibilékrou climate—sustained progress over the MARAHOUE Bocanda LACS Daoukro Bangolo Bouaflé 7°N 7°N Daloa YAMOUSSOUKRO Marahoue last four years as measured by Doing Duekoue o Abengourou b GHANA o YAMOUSSOUKRO Dimbokro L Sinfra Guiglo Bongouanou Indenie- Toulepleu Toumodi N'Zi Djuablin Business, Global Competitiveness, Oumé Cavally Issia Belier To Gôh CÔTE D'IVOIRE Monrovia