[Sample Title Page]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Children in Opera

Children in Opera Children in Opera By Andrew Sutherland Children in Opera By Andrew Sutherland This book first published 2021 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2021 by Andrew Sutherland Front cover: ©Scott Armstrong, Perth, Western Australia All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-6166-6 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-6166-3 In memory of Adrian Maydwell (1993-2019), the first Itys. CONTENTS List of Figures........................................................................................... xii Acknowledgements ................................................................................. xxi Chapter 1 .................................................................................................... 1 Introduction What is a child? ..................................................................................... 4 Vocal development in children ............................................................. 5 Opera sacra ........................................................................................... 6 Boys will be girls ................................................................................. -

Categorization of Vocal Fry in Running Speech

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU Honors Projects Honors College Fall 12-2019 Categorization of Vocal Fry in Running Speech Katherine Proctor [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/honorsprojects Part of the Laboratory and Basic Science Research Commons Repository Citation Proctor, Katherine, "Categorization of Vocal Fry in Running Speech" (2019). Honors Projects. 549. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/honorsprojects/549 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. CATEGORIZATION OF VOCAL FRY IN RUNNING SPEECH CATEGORIZATION OF VOCAL FRY IN RUNNING SPEECH KATHERINE PROCTOR HONORS PROJECT Submitted to the Honors College at Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with UNIVERSITY HONORS 12/9/19 Dr. Ronald Scherer, Communication Sciences and Disorders, College of Health and Human Services, Advisor Dr. Katherine Meizel, Musicology/Ethnomusicology, College of Musical Arts, Advisor 1 CATEGORIZATION OF VOCAL FRY IN RUNNING SPEECH INTRODUCTION The concept of a vocal register has been defined by Hollien (1974) as “a series or range of consecutive frequencies that can be produced with nearly identical voice quality.” There are three different vocal registers in speech production according to Hollien (1974). These registers are: loft, which is the highest of the three, and could be described perceptually as the “falsetto” range; modal, which is the middle range and is evident in “normal” speech production; and pulse, the lowest range of phonation that is characterized by popping, pulsing sounds. -

Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 4-15-2018 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Bourne, Thaddaeus, "Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1779. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1779 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus James Bourne, DMA University of Connecticut, 2018 This study will examine the Zwischenfach colloquially referred to as the baritenor. A large body of published research exists regarding the physiology of breathing, the acoustics of singing, and solutions for specific vocal faults. There is similarly a growing body of research into the system of voice classification and repertoire assignment. This paper shall reexamine this research in light of baritenor voices. After establishing the general parameters of healthy vocal technique through appoggio, the various tenor, baritone, and bass Fächer will be studied to establish norms of vocal criteria such as range, timbre, tessitura, and registration for each Fach. The study of these Fächer includes examinations of the historical singers for whom the repertoire was created and how those roles are cast by opera companies in modern times. The specific examination of baritenors follows the same format by examining current and -

Using Italian

This page intentionally left blank Using Italian This is a guide to Italian usage for students who have already acquired the basics of the language and wish to extend their knowledge. Unlike conventional grammars, it gives special attention to those areas of vocabulary and grammar which cause most difficulty to English speakers. Careful consideration is given throughout to questions of style, register, and politeness which are essential to achieving an appropriate level of formality or informality in writing and speech. The book surveys the contemporary linguistic scene and gives ample space to the new varieties of Italian that are emerging in modern Italy. The influence of the dialects in shaping the development of Italian is also acknowledged. Clear, readable and easy to consult via its two indexes, this is an essential reference for learners seeking access to the finer nuances of the Italian language. j. j. kinder is Associate Professor of Italian at the Department of European Languages and Studies, University of Western Australia. He has published widely on the Italian language spoken by migrants and their children. v. m. savini is tutor in Italian at the Department of European Languages and Studies, University of Western Australia. He works as both a tutor and a translator. Companion titles to Using Italian Using French (third edition) Using Italian Synonyms A guide to contemporary usage howard moss and vanna motta r. e. batc h e lor and m. h. of f ord (ISBN 0 521 47506 6 hardback) (ISBN 0 521 64177 2 hardback) (ISBN 0 521 47573 2 paperback) (ISBN 0 521 64593 X paperback) Using French Vocabulary Using Spanish jean h. -

Rossini Propició El Futuro De La Ópera

www.proopera.org.mx • año XXVI • número 1 • enero – febrero 2018 • sesenta pesos ENTREVISTAS Andeka Gorrotxategi Óscar Martínez ENTREVISTAS EN LÍNEA Mojca Erdmann Nancy Fabiola Herrera Willy Anthony Waters FESTIVALES Cervantino XLV OBITUARIO Dmitri Hvorostovsky JohnJohn OsbornOsborn “Rossini“Rossini propiciópropició el futuro de la ópera”pro opera¾ DIRECTORIO REVISTA COMITÉ EDITORIAL Adriana Alatriste índice Luis Gutiérrez Ruvalcaba Andrea Labastida Charles H. Oppenheim 3 Carta del Presidente FUNDADOR Y DIRECTOR EMÉRITO CONCIERTOS Xavier Torres Arpi 4 Juan Diego Flórez: Canto a México EDITOR Charles H. Oppenheim 6 En breve 6 [email protected] CORRECCIÓN DE ESTILO CRÍTICA Darío Moreno 8 Otello en Bellas Artes COLABORAN EN ESTE NÚMERO 10 Ópera en México Othón Canales Treviño Carlos Fuentes y Espinosa Luis Gutiérrez Ruvalcaba PROTAGONISTAS Ingrid Haas 12 Andeka Gorrotxategi: Ramón Jacques “Me encantaría tener puestas José Noé Mercado todas las óperas de Puccini” David Rimoch Vladimiro Rivas Iturralde RESEÑA Gamaliel Ruiz 15 Arreglo de bodas en el Cenart José Andrés Tapia Osorio David Josué Zambrano de León 16 Ópera en los estados 15 www.proopera.org.mx. FESTIVALES CORRESPONSALES EN ESTE NÚMERO 20 Cervantino XLV Eduardo Benarroch Francesco Bertini Abigaíl Brambila ENTREVISTA Jorge Binaghi 22 Óscar Martínez: John Koopman Un cantante versátil Daniel Lara y un maestro ecléctico Gregory Moomjy Maria Nockin OBITUARIO Gustavo Gabriel Otero 25 Dmitri Hvorostovsky (1962-2017) Joel Poblete Roberto San Juan Ximena Sepúlveda PORTADA Massimo Viazzo 26 John Osborn: “Rossini propició el futuro de la ópera” FOTOGRAFIA Ana Lourdes Herrera ESTRENO 25 DISEÑO GRAFICO 32 La degradación de la burguesía: Ida Noemí Arellano Bolio The Exterminating Angel, desde Nueva York DISEÑO PÁGINA WEB TESTIMONIAL Christiane Kuri – Espacio Azul 34 Pro Ópera en Los Ángeles DISEÑO LOGO 36 México en el mundo Ricardo Gil Rizo IMPRESION ÓPERA EN EL MUNDO Grupo Gama. -

Common Opera Terminology

Common Opera Terminology acoustics The science of sound; qualities which determine hearing facilities in an auditorium, concert hall, opera house, theater, etc. act A section of the opera, play, etc. usually followed by an intermission. arias and recitative Solos sung by one person only. Recitative, are sung words and phrases that are used to propel the action of the story and are meant to convey conversations. Melodies are often simple or fast to resemble speaking. The aria is like a normal song with more recognizable structure and melody. Arias, unlike recitative, are a stop in the action, where the character usually reflects upon what has happened. When two people are singing, it becomes a duet. When three people sing a trio, four people a quartet. backstage The area of the stage not visible to the audience, usually where the dressing rooms are located. bel canto Although Italian for “beautiful song,” the term is usually applied to the school of singing prevalent in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Baroque and Romantic) with emphasis on vocal purity, control, and dexterity blocking Directions given to actors for on-stage movements and actions bravo, brava, bravi An acknowledgement of a good performance shouted during moments of applause (the ending is determined by the gender and the number of performers). cadenza An elaborate passage near the end of an aria, which shows off the singer’s vocal ability. chorus master Person who prepares the chorus musically (which includes rehearsing and directing them). coloratura A voice that can sing music with many rapid notes, or the music written for such a voice with elaborate ornamentation using fast notes and trills. -

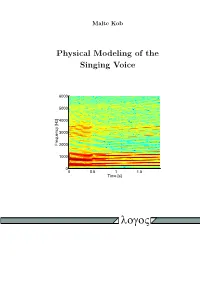

Physical Modeling of the Singing Voice

Malte Kob Physical Modeling of the Singing Voice 6000 5000 4000 3000 Frequency [Hz] 2000 1000 0 0 0.5 1 1.5 Time [s] logoV PHYSICAL MODELING OF THE SINGING VOICE Von der FakulÄat furÄ Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik der Rheinisch-WestfÄalischen Technischen Hochschule Aachen zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines DOKTORS DER INGENIEURWISSENSCHAFTEN genehmigte Dissertation vorgelegt von Diplom-Ingenieur Malte Kob aus Hamburg Berichter: UniversitÄatsprofessor Dr. rer. nat. Michael VorlÄander UniversitÄatsprofessor Dr.-Ing. Peter Vary Professor Dr.-Ing. JuÄrgen Meyer Tag der muÄndlichen PruÄfung: 18. Juni 2002 Diese Dissertation ist auf den Internetseiten der Hochschulbibliothek online verfuÄgbar. Die Deutsche Bibliothek – CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Kob, Malte: Physical modeling of the singing voice / vorgelegt von Malte Kob. - Berlin : Logos-Verl., 2002 Zugl.: Aachen, Techn. Hochsch., Diss., 2002 ISBN 3-89722-997-8 c Copyright Logos Verlag Berlin 2002 Alle Rechte vorbehalten. ISBN 3-89722-997-8 Logos Verlag Berlin Comeniushof, Gubener Str. 47, 10243 Berlin Tel.: +49 030 42 85 10 90 Fax: +49 030 42 85 10 92 INTERNET: http://www.logos-verlag.de ii Meinen Eltern. iii Contents Abstract { Zusammenfassung vii Introduction 1 1 The singer 3 1.1 Voice signal . 4 1.1.1 Harmonic structure . 5 1.1.2 Pitch and amplitude . 6 1.1.3 Harmonics and noise . 7 1.1.4 Choir sound . 8 1.2 Singing styles . 9 1.2.1 Registers . 9 1.2.2 Overtone singing . 10 1.3 Discussion . 11 2 Vocal folds 13 2.1 Biomechanics . 13 2.2 Vocal fold models . 16 2.2.1 Two-mass models . 17 2.2.2 Other models . -

Kenneth E. Querns Langley Doctor of Philosophy

Reconstructing the Tenor ‘Pharyngeal Voice’: a Historical and Practical Investigation Kenneth E. Querns Langley Submitted in partial fulfilment of Doctor of Philosophy in Music 31 October 2019 Page | ii Abstract One of the defining moments of operatic history occurred in April 1837 when upon returning to Paris from study in Italy, Gilbert Duprez (1806–1896) performed the first ‘do di petto’, or high c′′ ‘from the chest’, in Rossini’s Guillaume Tell. However, according to the great pedagogue Manuel Garcia (jr.) (1805–1906) tenors like Giovanni Battista Rubini (1794–1854) and Garcia’s own father, tenor Manuel Garcia (sr.) (1775–1832), had been singing the ‘do di petto’ for some time. A great deal of research has already been done to quantify this great ‘moment’, but I wanted to see if it is possible to define the vocal qualities of the tenor voices other than Duprez’, and to see if perhaps there is a general misunderstanding of their vocal qualities. That investigation led me to the ‘pharyngeal voice’ concept, what the Italians call falsettone. I then wondered if I could not only discover the techniques which allowed them to have such wide ranges, fioritura, pianissimi, superb legato, and what seemed like a ‘do di petto’, but also to reconstruct what amounts to a ‘lost technique’. To accomplish this, I bring my lifelong training as a bel canto tenor and eighteen years of experience as a classical singing teacher to bear in a partially autoethnographic study in which I analyse the most important vocal treatises from Pier Francesco Tosi’s (c. -

The Harmonic Oscillator

Appendix A The Harmonic Oscillator Properties of the harmonic oscillator arise so often throughout this book that it seemed best to treat the mathematics involved in a separate Appendix. A.1 Simple Harmonic Oscillator The harmonic oscillator equation dates to the time of Newton and Hooke. It follows by combining Newton’s Law of motion (F = Ma, where F is the force on a mass M and a is its acceleration) and Hooke’s Law (which states that the restoring force from a compressed or extended spring is proportional to the displacement from equilibrium and in the opposite direction: thus, FSpring =−Kx, where K is the spring constant) (Fig. A.1). Taking x = 0 as the equilibrium position and letting the force from the spring act on the mass: d2x M + Kx = 0. (A.1) dt2 2 = Dividing by the mass and defining ω0 K/M, the equation becomes d2x + ω2x = 0. (A.2) dt2 0 As may be seen by direct substitution, this equation has simple solutions of the form x = x0 sin ω0t or x0 = cos ω0t, (A.3) The original version of this chapter was revised: Pages 329, 330, 335, and 347 were corrected. The correction to this chapter is available at https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92796-1_8 © Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2018 329 W. R. Bennett, Jr., The Science of Musical Sound, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92796-1 330 A The Harmonic Oscillator Fig. A.1 Frictionless harmonic oscillator showing the spring in compressed and extended positions where t is the time and x0 is the maximum amplitude of the oscillation. -

Patterns of Vocal Fold Closure in Professional Singers

PATTERNS OF VOCAL FOLD CLOSURE IN PROFESSIONAL SINGERS CARIE VOLKAR Master of Music in Voice Performance University of Akron May 2005 submitted in partial fulfillment of requirement for the degree MASTER OF ARTS IN SPEECH-LANGUAGE PATHOLOGY AND AUDIOLOGY at the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY MAY 2017 We hereby approve this thesis for Carie Volkar Candidate for the Master of Arts in Speech Pathology and Audiology degree for the Department of Speech and Hearing and the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY’S College of Graduate Studies by Thesis Chairperson, Violet O. Cox, Ph.D., CCC-SLP _____________________________________________ Department & Date Thesis Committee Member, Myrita Wilhite, Au.D. _____________________________________________ Department & Date Thesis Committee Member, Brian Bailey, D.M.A. _____________________________________________ Department & Date Student’s Date of Defense: May 2, 2017 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to take this opportunity to thank all those who guided me through this process. I would like to thank my family for their love and support throughout my life and education. I would also like to thank my friends for always being there for me and pushing me to take care of myself while in the program. I would like to express my most sincere gratitude to my thesis chairperson, Dr. Violet Cox for her mentorship throughout my thesis and this program. I would like to thank her for the enthusiasm and passion she shared for my research topic. I would like to thank her for training me in stroboscopy and for being the methodologist in my investigation. I thank her for her patience and motivation to finish this step towards completing my Master’s degree. -

Ingressive Phonation in Contemporary Vocal Music, Works by Helmut Lachenmann, Georges Aperghis, Michael Baldwin, and Nicholas

© 2012 Amanda DeBoer Bartlett All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jane Schoonmaker Rodgers, Advisor The use of ingressive phonation (inward singing) in contemporary vocal music is becoming more frequent, yet there is limited research on the physiological demands, risks, and pedagogical requirements of the various ingressive phonation techniques. This paper will discuss ingressive phonation as it is used in contemporary vocal music. The research investigates the ways in which ingressive phonation differs acoustically, physiologically, and aesthetically from typical (egressive) phonation, and explores why and how composers and performers use the various ingressive vocal techniques. Using non-invasive methods, such as electroglottograph waveforms, aerodynamic (pressure, flow, flow resistance) measures, and acoustic analyses of recorded singing, specific data about ingressive phonation were obtained, and various categories of vocal techniques were distinguished. Results are presented for basic vocal exercises and tasks, as well as for specific excerpts from the repertoire, including temA by Helmut Lachenmann and Ursularia by Nicholas DeMaison. The findings of this study were applied to a discussion surrounding pedagogical and aesthetic applications of ingressive phonation in contemporary art music intended for concert performance. Topics of this discussion include physical differences in the production and performance of ingressive phonation, descriptive information regarding the various techniques, as well as notational and practical recommendations for composers. iv This document is dedicated to: my husband, Tom Bartlett my parents, John and Gail DeBoer and my siblings, Mike, Matt, and Leslie DeBoer Thank you for helping me laugh through the process – at times ingressively – and for supporting me endlessly. v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I have endless gratitude for my advisor and committee chair, Dr. -

Minnesota Opera House

O p e r a B o x Teacher’s Guide table of contents Welcome Letter . .1 Lesson Plan Unit Overview and Academic Standards . .2 Lesson Plans . .12 Synopsis . .31 Giuseppe Verdi – a biography ...............................37 Catalogue of Verdi’s Operas . .39 Background Notes . .41 “That Scottish Play” . .45 History of Opera ........................................49 2013–2014 SEASON History of Minnesota Opera, Repertoire . .60 GIACOMO PUCCINI The Standard Repertory ...................................64 SEPTEMBER 21 –SEPTEMBER 29, 2013 Elements of Opera .......................................65 RICHARD STRAUSS Glossary of Opera Terms ..................................69 NOVEMBER 9 – 17, 2013 Glossary of Musical Terms .................................75 GIUSEPPE VERDI Bibliography, Discography, Videography . .78 JANUARY 25 –FEBRUARY 2, 2014 Acknowledgements . .81 DOMINICK ARGENTO MARCH 1 – 9, 2014 WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART APRIL 12 – 27, 2014 FOR SEASON TICKETS, CALL 612.333.6669 mnopera.org 620 North First Street, Minneapolis, MN 55401 Kevin Ramach, PRESIDENT AND GENERAL DIRECTOR Dale Johnson, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Dear Educator, Thank you for using a Minnesota Opera Teacher’s Guide, which includes Lesson Plans that have been aligned with State and National Standards. See the Unit Overview for a detailed explanation. Since opera is first and foremost a theatrical experience, it is strongly encouraged that attendance at a performance of an opera be included. The Minnesota Opera offers Student Final Dress Rehearsals and discounted group rate tickets to regular performances. It is hoped that the Teacher’s Guide will be the first step into exploring opera, and attending will be the next. I hope you enjoy these materials and find them helpful. If I can be of any assistance, please feel free to call or e-mail me any time.