Schools in Ireland? Analysing Feeder School Performance Using Student Destination Data

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vocation Spirituality Engagement

SPRING 2014 Vocation Engagement Spirituality AN INTERNATIONAL MARIST JOURNAL OF CHARISM IN EDUCATION volume 16 | number 03 | 2014 Inside: • The Prophet Ezekiel for us today • Catholic Education in Aotearoa New Zealand Schools • Living the Joy of the Gospel Champagnat: An International Marist Journal of Charism in Education aims to assist its readers to integrate charism into education in a way that gives great life and hope. Marists provide one example of this mission. Editor Champagnat: An International Marist Journal of Tony Paterson FMS Charism in Education, ISSN 1448-9821, is [email protected] published three times a year by Marist Publishing Mobile: 0409 538 433 Peer-Review: Management Committee The papers published in this journal are peer- reviewed by the Management Committee or their Michael Green FMS delegates. Lee McKenzie Tony Paterson FMS (Chair) Correspondence: Roger Vallance FMS Br Tony Paterson, FMS Marist Centre, Peer-Reviewers PO Box 1247, The papers published in this journal are peer- MASCOT, NSW, 1460 reviewed by the Management Committee or their Australia delegates. The peer-reviewers for this edition were: Email: [email protected] Michael McManus FMS Views expressed in the articles are those of the respective authors and not necessarily those of Tony Paterson FMS the editors, editorial board members or the Kath Richter publisher. Roger Vallance FMS Unsolicited manuscripts may be submitted and if not accepted will be returned only if accompanied by a self-addressed envelope. Requests for permission -

Irish Schools Athletics Champions 1916-2015 Updated June 15 2015

Irish Schools Athletics Champions 1916-2015 Updated June 15 2015 In February 1916 Irish Amateur Athletic Association (IAAA) circularised the principal schools in Ireland regarding the advisability of holding Schoolboys’ Championships. At the IAAA’s Annual General Meeting held on Monday 3rd April, 1916 in Wynne’s Hotel, Dublin, the Hon. Secretary, H.M. Finlay, referred to the falling off in the number of affiliated clubs due to the number of athletes serving in World War I and the need for efforts to keep the sport alive. Based on responses received from schools, the suggestion to hold Irish Schoolboys’ Championships in May was favourably considered by the AGM and the Race Committee of the IAAA was empowered to implement this project. Within a week a provisional programme for the inaugural athletics meeting to be held at Lansdowne Road on Saturday 20th May, 1916 had been published in newspapers, with 7 events and a relay for Senior and 4 events and a relay for Junior Boys. However, the championships were postponed "due to the rebellion" and were rescheduled to Saturday 23rd September, 1916, at Lansdowne Road. In order not to disappoint pupils who were eligible for the championships on the original date of the meeting, the Race Committee of the IAAA decided that “a bona fide schoolboy is one who has attended at least two classes daily at a recognised primary or secondary school for three months previous to 20 th May, except in case of sickness, and who was not attending any office or business”. The inaugural championships took place in ‘quite fine’ weather. -

NAPD Conference 2016 Workshop Registrations

NAPD Conference 2016 Workshop Registrations Name School Position NAPD Region Conference Workshop Data Protection in the Digital Era and Energy Mary O Sullivan Scoil Phobail Bhéara Principal Region 7 (Cork) Efficient Computing (Cloud School) Region 1 (Cavan, Donegal, Data Protection in the Digital Era and Energy rosaleen Grant scoil mhuire, Buncrana Principal Leitrim, Monaghan, Sligo) Efficient Computing (Cloud School) Region 2 (Galway, Mayo, Data Protection in the Digital Era and Energy Catherine Hickey Coláiste Iognáid Deputy Principal Roscommon) Efficient Computing (Cloud School) Region 6 (Clare, Kerry, Data Protection in the Digital Era and Energy Pat Fleming Mercy Mounthawk Deputy Principal Limerick) Efficient Computing (Cloud School) Data Protection in the Digital Era and Energy Siobhán Kelly Muckross Park College Deputy Principal Region 8 (Dublin) Efficient Computing (Cloud School) Region 1 (Cavan, Donegal, Data Protection in the Digital Era and Energy Jacqueline Dillon Magh Ene College Principal Leitrim, Monaghan, Sligo) Efficient Computing (Cloud School) Region 6 (Clare, Kerry, Data Protection in the Digital Era and Energy Sean Lane Scoil Mhuire Agus Ide Deputy Principal Limerick) Efficient Computing (Cloud School) Sancta Maria College Ballyroan Data Protection in the Digital Era and Energy Gerardine Kennedy Rathfarnham Dublin 16 Principal Region 9 (Dublin) Efficient Computing (Cloud School) St. Joseph's Patrician College, Region 2 (Galway, Mayo, Data Protection in the Digital Era and Energy John Madden Galway Deputy Principal -

Statement of Consistency

STATEMENT OF CONSISTENCY FOR A BUILD TO RENT (BTR) RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT AT ‘MARMALADE LANE’, DUNDRUM, DUBLIN 16. PREPARED BY ON BEHALF OF 1 Wyckham Land Limited SEPTEMBER 2020 CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................. 3 2. NATIONAL & REGIONAL PLANNING POLICY .................................... 6 3 LOCAL PLANNING POLICY ............................................................. 40 4 CONCLUDING REMARKS ............................................................... 49 2 1. INTRODUCTION On behalf of the applicant, 1 Wyckham Land Limited, this Statement of Consistency accompanies a planning application to An Bord Pleanála for a proposed Strategic Housing Development on lands located at Marmalade Lane, Gort Muire, Dundrum, Dublin 16, in accordance with Section 5 of the Planning and Development (Housing) and Residential Tenancies Act 2016. The site is located to the east of Gort Muire, Carmelite Centre, and is accessed from Wyckham Avenue, off Wyckham Way. The application site includes lands formerly part of/owned by the Gort Muire Carmelite Centre and is located adjacent to Protected Structures (RPS No. 1453). It comprises an open field having formerly been used as agricultural lands. The boundaries are delineated by modern post and rail fencing with some mature trees along the boundaries. There are no built structures on the site. The development will comprise a ‘Build to Rent’ (BTR) apartment development consisting of 7 no. blocks ranging in height up to 9 storeys (and -

Ireuso 2014-2015 Finalists

IrEUSO 2014-2015 Finalists Dublin City University, 1st November 2014 First name Surname School Rizwan Ahmad Colaiste Phadraig C.B.S , Lucan, Dublin Mariam Ahmed Ursuline College Sligo, Finisklin, Sligo Arsalan Akram De La Salle College, Waterford, Waterford Gráinne Allen East Glendalough School, Wicklow , Wicklow Abdulladh Amin Colaiste Eamonn Ris, Wexford , Wexford Grant Arnott Wesley College , Ballinteer , Dublin 16 Christopher Aylward Blackrock College, Blackrock, Dublin 6 Aiman Azam Mean Scoil Mhuire , Longford Town , Longford James Baker Coola Post Primary, Riverstown via Boyle, Co Sligo Fergus Balfe De La Salle College, Churchtown, Dublin 14 Kate Barr Muckross Park College, Donnybrook, Dublin 4 Joyce Barry Mount Mercy College , Model Farm Road , Cork Killian Beashel St Gerards , Bray, Co Wicklow Emma Beatty Holy Faith Secondary School, Clontarf , Dublin 3 Sean Behán Mean Scoil Ognaid Ris , Naas , Co Kildare Ryan Bell Oatlands College, Stillorgan, Co Dublin Adam Blaq Rice College, Westport, Co Mayo Cillian Boland Blackrock College, Blackrock, Co Dublin Drew Boland CBS Nenagh, Summerhill, Co Tipperary Una Boland Dominican College, Muckross, Dublin 4 Bronagh Bolger Loreto Secondary School, Fermoy, Co Cork Arianna Bonner St. Columba's Comprehensive School , Glenties , Co Donegal Aoife Booth Ursuline Secondary School, Thurles , Tipperary Adam Bowden Ard Scoil Na Trionoide , Athy , Kildare Jack Boylan St. Mary's College , Dundalk , Louth Éile Breslin Holy Faith Clontarf, Clontarf, Dublin 3 Matthew Brohan Colaiste Choilm, Ballincollig, Co Cork Ciara Brown St. Olivers P.P. School , Cavan Road , Meath Ciara Browne Carrigaline Community School, Carrigaline , Cork Jordan Buckley S. Jarlath's College , Tuam, Galway Orlaith Buckley Seamount College , Kinvara , Co Galway Andrew Burgess Wesley College, Ballinteer, Dublin 16 Eamonn Byrne St. -

S-School Code S-School STREET LINE1 STREET LINE2

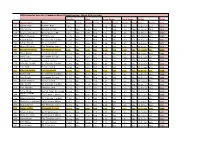

Count of Enrolments S-School Code S-School STREET_LINE1 STREET_LINE2 STREET_LINE3 CITY F M Total 3333 (external Candidate) None 1 1 42327T Leinster Senior College The Courtyard Newbridge Co Kildare 3 2 5 42676V Ashfield College Sandyford Rd Dundrum Dublin 16 4 4 50002K Institute Of Education Leeson Street Dublin 2 2 4 6 60041D Colaiste Eoin Br Stigh Lorgan Baile An Bhothair Blackrock Dublin 2 2 60042F Colaiste Iosagain Br Stigh Lorgan Baile An Bhothair Blackrock Dublin 2 2 60050E Oatlands College Mount Merrion An Charraig Dhubh Co Bhaile Atha Cliat 1 1 60070K Dominican College Sion Hill Blackrock Co. Dublin 1 1 60081P Presentation Convent Rockford Manor An Charraig Dhubh Co Bhaile Atha Cliat 1 1 60092U Clonkeen College Clonkeen Road Blackrock Co. Dublin. 2 2 60121B Moyle Park College Clondalkin Dublin 22 22 22 60122D Colaiste Bride Cluain Dolcain Baile Atha Cliath 22 25 25 60130C Loreto Abbey Dalkey Co Dublin 2 2 60240J Loreto Secondary School Foxrock Dublin 18 1 1 60250M Holy Child School Military Road Killiney Co. Dublin. 1 1 60260P St Joseph Of Cluny Sec.School Bellevue Park Ballinclea Rd Dun Laoghaire 1 1 60261R St. Benildus College Upper Kilmacud Road Stillorgan Blackrock Dublin 12 12 60262T St. Laurences College Loughlinstown Shankill Dublin 18 1 2 3 60263V Colaiste Ioseph Naofa Clochar Na Toirbhirte Leamhcan Co. Bhaile Atha Clia 7 7 60264A Colaiste Padraig Cbs Roselawn Lucan Co Dublin 9 9 60272W The Kings Hospital Palmerstown Dublin 20 1 1 2 60290B St Pauls College Sybil Hill Raheny Dublin 5 1 1 60300B Manor House School Raheny -

Total Numberathlete Name School Time Points Distancepoints

2018 Leinster Schools, Combined Event Championships, Minor Girls Scoring Hurdles Shot Long Jump High Jump 800m Total NumberAthlete Name School Time Points DistancePoints Distance Points Height Points Time Points Point 191 Saidbh Byrne Colaiste Brid 9.68 773 9.55 500 4.64 464 1.48 599 02:49.14 473 2809 179 Laura Kelly Rotoath College 10.35 648 8.38 424 4.07 324 1.48 599 02:28.36 714 2709 187 Grainne O'Sullivan North Wicklow ET 9.94 723 6.75 319 4.71 482 1.33 439 02:35.16 630 2593 185 Orlaith Deegan FCJ Bunclody 10.52 618 7.17 346 4.26 369 1.51 632 02:35.83 622 2587 170 Niamh Brady St. Vincents Dundalk 10.46 629 7.37 359 4.25 367 1.39 502 02:39.07 584 2441 192 Sohpie Myers St. Leos Carlow 10.01 710 8.22 414 4.49 426 1.25 359 02:49.62 468 2377 198 Grace O'Connor The Teresian School 10.37 644 5.49 239 4.08 326 1.39 502 02:38.30 593 2304 196 Abigaial Kennedy The Teresian School 9.83 744 8.78 450 4.05 319 1.33 439 03:04.95 321 2273 176 Emer Halpin Loreto Wexford 10.37 644 7.09 341 3.92 290 1.25 359 02:34.83 634 2268 203 Emily Lyne Alexandra College 10.59 606 6.45 300 4.10 331 1.42 534 02:47.44 491 2262 180 Caoimhe Fitzsimons Rotoath College 10.63 599 7.71 381 4.46 418 1.25 359 02:47.62 489 2246 173 Julie McLoughlin St. -

Youth and Sport Development Services

Youth and Sport Development Services Socio-economic profile of area and an analysis of current provision 2018 A socio economic analysis of the six areas serviced by the DDLETB Youth Service and a detailed breakdown of the current provision. Contents Section 3: Socio-demographic Profile OVERVIEW ........................................................................................................... 7 General Health ........................................................................................................................................................... 10 Crime ......................................................................................................................................................................... 24 Deprivation Index ...................................................................................................................................................... 33 Educational attainment/Profile ................................................................................................................................. 38 Key findings from Socio Demographic Profile ........................................................................................................... 42 Socio-demographic Profile DDLETB by Areas an Overview ........................................................................................... 44 Demographic profile of young people ....................................................................................................................... 44 Pobal -

Official Handbook 2019/2020 Title Partner Official Kit Partner

OFFICIAL HANDBOOK 2019/2020 TITLE PARTNER OFFICIAL KIT PARTNER PREMIUM PARTNERS PARTNERS & SUPPLIERS MEDIA PARTNERS www.leinsterrugby.ie | From The Ground Up COMMITTEES & ORGANISATIONS OFFICIAL HANDBOOK 2019/2020 Contents Leinster Branch IRFU Past Presidents 2 COMMITTEES & ORGANISATIONS Leinster Branch Officers 3 Message from the President Robert Deacon 4 Message from Bank of Ireland 6 Leinster Branch Staff 8 Executive Committee 10 Branch Committees 14 Schools Committee 16 Womens Committee 17 Junior Committee 18 Youths Committee 19 Referees Committee 20 Leinster Rugby Referees Past Presidents 21 Metro Area Committee 22 Midlands Area Committee 24 North East Area Committee 25 North Midlands Area Committee 26 South East Area Committee 27 Provincial Contacts 29 International Union Contacts 31 Committee Meetings Diary 33 COMPETITION RESULTS European, UK & Ireland 35 Leagues In Leinster, Cups In Leinster 39 Provincial Area Competitions 40 Schools Competitions 43 Age Grade Competitions 44 Womens Competitions 47 Awards Ball 48 Leinster Rugby Charity Partners 50 FIXTURES International 51 Heineken Champions Cup 54 Guinness Pro14, Celtic Cup 57 Leinster League 58 Seconds League 68 Senior League 74 Metro League 76 Energia All Ireland League 89 Energia Womens AIL League 108 CLUB & SCHOOL INFORMATION Club Information 113 Schools Information 156 www.leinsterrugby.ie 1 OFFICIAL HANDBOOK 2019/2020 COMMITTEES & ORGANISATIONS Leinster Branch IRFU Past Presidents 1920-21 Rt. Rev. A.E. Hughes D.D. 1970-71 J.F. Coffey 1921-22 W.A. Daish 1971-72 R. Ganly 1922-23 H.J. Millar 1972-73 A.R. Dawson 1923-24 S.E. Polden 1973-74 M.H. Carroll 1924-25 J.J. Warren 1974-75 W.D. -

Definitive Guide to the Top 500 Schools in Ireland

DEFINITIVE GUIDE TO THE TOP 500 SCHOOLS IN IRELAND These are the top 500 secondary schools ranked by the average proportion of pupils gaining places in autumn 2017, 2018 and 2019 at one of the 10 universities on the island of Ireland, main teacher training colleges, Royal College of Surgeons or National College of Art and Design. Where schools are tied, the proportion of students gaining places at all non-private, third-level colleges is taken into account. See how this % at university Boys Girls Student/ staff ratio Telephone % at third-level Area Type % at university Boys Girls Student/ staff ratio Telephone Rank Previous rank % at third-level Type % at university Boys Girls Student/ staff ratio Telephone Area Type Rank Previous rank Area % at third-level guide was compiled, back page. Schools offering only senior cycle, such as the Institute of Education, Dublin, and any new schools are Rank Previous rank excluded. Compiled by William Burton and Colm Murphy. Edited by Ian Coxon 129 112 Meanscoil Iognaid Ris, Naas, Co Kildare L B 59.9 88.2 1,019 - 14.1 045-866402 269 317 Rockbrook Park School, Rathfarnham, Dublin 16 SD B 47.3 73.5 169 - 13.4 01-4933204 409 475 Gairmscoil Mhuire, Athenry, Co Galway C M 37.1 54.4 266 229 10.0 091-844159 Fee-paying schools are in bold. Gaelcholaisti are in italics. (G)=Irish-medium Gaeltacht schools. *English-speaking schools with Gaelcholaisti 130 214 St Finian’s College, Mullingar, Co Westmeath L M 59.8 82.0 390 385 13.9 044-48672 270 359 St Joseph’s Secondary School, Rush, Co Dublin ND M 47.3 63.3 416 297 12.3 01-8437534 410 432 St Mogue’s College, Belturbet, Co Cavan U M 37.0 59.0 123 104 10.6 049-9523112 streams or units. -

Welcome to Transition Year 2019-20

Welcome to Transition Year 2019-20 Transition Year Programme Introduction: The Mission: The Transition Year programme in Loreto College Foxrock offers each student a broad holistic curriculum enabling her to develop her own particular gifts, reach her full potential and to develop a love of learning. Every opportunity is given to enable students to develop powers of critical reflection thereby building independence of mind, increasing social awareness and social competences and nurturing maturation. It is hoped that by the end of Transition Year the programme will have contributed to the social development of these young teenagers so that they grow up to be autonomous, participative and responsible members of society. Overall Aims: Transition Year (TY) is a one-year school based programme designed to facilitate the smooth transition from the dependent learning of the Junior Cycle to the more independent, self-directed learning of the Senior Cycle – in effect it is designed to act as a bridge between Junior and Senior Cycle. The TY programme at Loreto College Foxrock provides a broad variety of learning experiences both inside and outside the classroom. The student’s experience of adult and working life contributes to their personal development and maturity. This, combined with the advancement of general, technical and academic skills, with the emphasis placed on interdisciplinary and self-directed learning are the cornerstones of the Transition Year programme as it is run by Loreto College Foxrock. These aims are interrelated and interdependent -

Contents • Abbreviations • International Education Codes • Us Education Codes • Canadian Education Codes July 1, 2021

CONTENTS • ABBREVIATIONS • INTERNATIONAL EDUCATION CODES • US EDUCATION CODES • CANADIAN EDUCATION CODES JULY 1, 2021 ABBREVIATIONS FOR ABBREVIATIONS FOR ABBREVIATIONS FOR STATES, TERRITORIES STATES, TERRITORIES STATES, TERRITORIES AND CANADIAN AND CANADIAN AND CANADIAN PROVINCES PROVINCES PROVINCES AL ALABAMA OH OHIO AK ALASKA OK OKLAHOMA CANADA AS AMERICAN SAMOA OR OREGON AB ALBERTA AZ ARIZONA PA PENNSYLVANIA BC BRITISH COLUMBIA AR ARKANSAS PR PUERTO RICO MB MANITOBA CA CALIFORNIA RI RHODE ISLAND NB NEW BRUNSWICK CO COLORADO SC SOUTH CAROLINA NF NEWFOUNDLAND CT CONNECTICUT SD SOUTH DAKOTA NT NORTHWEST TERRITORIES DE DELAWARE TN TENNESSEE NS NOVA SCOTIA DC DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA TX TEXAS NU NUNAVUT FL FLORIDA UT UTAH ON ONTARIO GA GEORGIA VT VERMONT PE PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND GU GUAM VI US Virgin Islands QC QUEBEC HI HAWAII VA VIRGINIA SK SASKATCHEWAN ID IDAHO WA WASHINGTON YT YUKON TERRITORY IL ILLINOIS WV WEST VIRGINIA IN INDIANA WI WISCONSIN IA IOWA WY WYOMING KS KANSAS KY KENTUCKY LA LOUISIANA ME MAINE MD MARYLAND MA MASSACHUSETTS MI MICHIGAN MN MINNESOTA MS MISSISSIPPI MO MISSOURI MT MONTANA NE NEBRASKA NV NEVADA NH NEW HAMPSHIRE NJ NEW JERSEY NM NEW MEXICO NY NEW YORK NC NORTH CAROLINA ND NORTH DAKOTA MP NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS JULY 1, 2021 INTERNATIONAL EDUCATION CODES International Education RN/PN International Education RN/PN AFGHANISTAN AF99F00000 CHILE CL99F00000 ALAND ISLANDS AX99F00000 CHINA CN99F00000 ALBANIA AL99F00000 CHRISTMAS ISLAND CX99F00000 ALGERIA DZ99F00000 COCOS (KEELING) ISLANDS CC99F00000 ANDORRA AD99F00000 COLOMBIA