A Guide to Common Oral Lesions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Picture of the Month

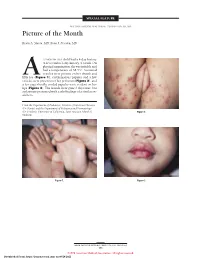

SPECIAL FEATURE SECTION EDITOR: WALTER W. TUNNESSEN, JR, MD Picture of the Month Kevin A. Slavin, MD; Ilona J. Frieden, MD 15-MONTH-OLD child had a 4-day history of fever and a 1-day history of a rash. On physical examination she was irritable and had a temperature of 38.3°C. Scattered vesicles were present on her thumb and Afifth toe (Figure 1), erythematous papules and a few vesicles were present over her perineum (Figure 2), and a few superficially eroded papules were evident on her lips (Figure 3). The lesions were gone 3 days later, but a playmate presented with early findings of a similar ex- anthem. From the Department of Pediatrics, Division of Infectious Diseases (Dr Slavin) and the Department of Pediatrics and Dermatology (Dr Frieden), University of California, San Francisco School of Figure 2. Medicine. Figure 1. Figure 3. ARCH PEDIATR ADOLESC MED/ VOL 152, MAY 1998 505 ©1998 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/28/2021 Denouement and Discussion Hand-Foot-and-Mouth Disease Figure 1. Vesicles are present on the thumb and fifth toe. foot-and-mouth disease).1,2,5-9 The lesions on the but- tocks are of the same size and typical of the early forms Figure 2. Multiple erythematous papules and a few scattered vesicles are of the exanthem, but they are not frequently vesicular present over the perineum. in nature. Lesions involving the perineum seem to be more Figure 3. Superficially eroded papules are present on the lips. common in children who wear diapers, suggesting that friction or minor trauma may play a role in the develop- ment of lesions. -

The Use of Biologic Agents in the Treatment of Oral Lesions Due to Pemphigus and Behçet's Disease: a Systematic Review

Davis GE, Sarandev G, Vaughan AT, Al-Eryani K, Enciso R. The Use of Biologic Agents in the Treatment of Oral Lesions due to Pemphigus and Behçet’s Disease: A Systematic Review. J Anesthesiol & Pain Therapy. 2020;1(1):14-23 Systematic Review Open Access The Use of Biologic Agents in the Treatment of Oral Lesions due to Pemphigus and Behçet’s Disease: A Systematic Review Gerald E. Davis II1,2, George Sarandev1, Alexander T. Vaughan1, Kamal Al-Eryani3, Reyes Enciso4* 1Advanced graduate, Master of Science Program in Orofacial Pain and Oral Medicine, Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry of USC, Los Angeles, California, USA 2Assistant Dean of Academic Affairs, Assistant Professor, Restorative Dentistry, Meharry Medical College, School of Dentistry, Nashville, Tennessee, USA 3Assistant Professor of Clinical Dentistry, Division of Periodontology, Dental Hygiene & Diagnostic Sciences, Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry of USC, Los Angeles, California, USA 4Associate Professor (Instructional), Division of Dental Public Health and Pediatric Dentistry, Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry of USC, Los Angeles, California, USA Article Info Abstract Article Notes Background: Current treatments for pemphigus and Behçet’s disease, such Received: : March 11, 2019 as corticosteroids, have long-term serious adverse effects. Accepted: : April 29, 2020 Objective: The objective of this systematic review was to evaluate the *Correspondence: efficacy of biologic agents (biopharmaceuticals manufactured via a biological *Dr. Reyes Enciso, Associate Professor (Instructional), Division source) on the treatment of intraoral lesions associated with pemphigus and of Dental Public Health and Pediatric Dentistry, Herman Ostrow Behçet’s disease compared to glucocorticoids or placebo. School of Dentistry of USC, Los Angeles, California, USA; Email: [email protected]. -

Benign Cementoblastoma Associated with an Impacted Mandibular Third Molar – Report of an Unusual Case

Case Report Benign Cementoblastoma Associated with an Impacted Mandibular Third Molar – Report of an Unusual Case Chethana Dinakar1, Vikram Shetty2, Urvashi A. Shetty3, Pushparaja Shetty4, Madhvika Patidar5,* 1,3Senior Lecturer, 4Professor & HOD, Department of Oral Pathology and Microbiology, AB Shetty Memorial Institute of Dental Science, Mangaloge, 2Director & HOD, Nittee Meenakshi Institute of Craniofacial Surgery, Mangalore, 5Senior Lecturer, Department of Oral Pathology and Microbiology, Babu Banarasi Das College of Dental Sciences, Lucknow *Corresponding Author: Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Cementoblastoma is characterized by the formation of cementum-like tissue in direct connection with the root of a tooth. It is a rare lesion constituting less than 1% of all odontogenic tumors. We report a unique case of a large cementoblastoma attached to the lateral root surface of an impacted permanent mandibular third molar in a 33 year old male patient. The association of cementoblastomas with impacted teeth is a rare finding. Key Words: Odontogenic tumor, Cementoblastoma, Impacted teeth, Third molar, Cementum Access this article online opening limited to approximately 10mm. The swelling Quick Response was firm to hard in consistency and tender on palpation. Code: Website: Lymph nodes were not palpable. www.innovativepublication.com On radiographical examination, it showed a large, well circumscribed radiopaque mass attached to the lateral root surface of impacted permanent right mandibular DOI: 10.5958/2395-6194.2015.00005.3 third molar. The mass displayed a radiolucent area at the other end and was seen occupying almost the entire length of the ramus of mandible. The entire lesion was INTRODUCTION surrounded by a thin, uniform radiolucent line (Fig. -

Glossary for Narrative Writing

Periodontal Assessment and Treatment Planning Gingival description Color: o pink o erythematous o cyanotic o racial pigmentation o metallic pigmentation o uniformity Contour: o recession o clefts o enlarged papillae o cratered papillae o blunted papillae o highly rolled o bulbous o knife-edged o scalloped o stippled Consistency: o firm o edematous o hyperplastic o fibrotic Band of gingiva: o amount o quality o location o treatability Bleeding tendency: o sulcus base, lining o gingival margins Suppuration Sinus tract formation Pocket depths Pseudopockets Frena Pain Other pathology Dental Description Defective restorations: o overhangs o open contacts o poor contours Fractured cusps 1 ww.links2success.biz [email protected] 914-303-6464 Caries Deposits: o Type . plaque . calculus . stain . matera alba o Location . supragingival . subgingival o Severity . mild . moderate . severe Wear facets Percussion sensitivity Tooth vitality Attrition, erosion, abrasion Occlusal plane level Occlusion findings Furcations Mobility Fremitus Radiographic findings Film dates Crown:root ratio Amount of bone loss o horizontal; vertical o localized; generalized Root length and shape Overhangs Bulbous crowns Fenestrations Dehiscences Tooth resorption Retained root tips Impacted teeth Root proximities Tilted teeth Radiolucencies/opacities Etiologic factors Local: o plaque o calculus o overhangs 2 ww.links2success.biz [email protected] 914-303-6464 o orthodontic apparatus o open margins o open contacts o improper -

Keratocystic Odontogenic Tumour Mimicking As a Dentigerous Cyst – a Rare Case Report Dr

DOI: 10.21276/sjds.2017.4.3.16 Scholars Journal of Dental Sciences (SJDS) ISSN 2394-496X (Online) Sch. J. Dent. Sci., 2017; 4(3):154-157 ISSN 2394-4951 (Print) ©Scholars Academic and Scientific Publisher (An International Publisher for Academic and Scientific Resources) www.saspublisher.com Case Report Keratocystic Odontogenic Tumour Mimicking as a Dentigerous Cyst – A Rare Case Report Dr. K. Saraswathi Gopal1, Dr. B. Prakash vijayan2 1Professor and Head, Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, Meenakshi Ammal Dental College and Hospital, Chennai 2PG Student, Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, Meenakshi Ammal Dental College and Hospital, Chennai *Corresponding author Dr. B. Prakash vijayan Email: [email protected] Abstract: Keratocystic odontogenic tumor (KCOT) formerly known as odontogenic keratocyst (OKC), is considered a benign unicystic or multicystic intraosseous neoplasm and one of the most aggressive odontogenic lesions presenting relatively high recurrence rate and a tendency to invade adjacent tissue. On the other hand Dentigerous cyst (DC) is one of the most common odontogenic cysts of the jaws and rarely recurs. They were very similar in clinical and radiographic characteristics. In our case a pathological report following incisional biopsy turned out to be dentigerous cyst and later as Keratocystic odontogenic tumour following total excision. The treatment was chosen in order to prevent any pathological fracture. A recurrence was noticed after 2 months following which the lesion was surgically enucleated. At 2-years of follow-up, patient showed no recurrence. Keywords: Dentigerous cyst, Keratocystic odontogenic tumour (KCOT), Recurrence, Enucleation INTRODUCTION Keratocystic odontogenic tumour (KCOT) is a CASE REPORT rare developmental, epithelial and benign cyst of the A 17-year-old patient reported to the OP with a jaws of odontogenic origin with high recurrence rates. -

Rebamipide to Manage Stomatopyrosis in Oral Submucous Fibrosis 1Joanna Baptist, 2Shrijana Shakya, 3Ravikiran Ongole

JCDP Rebamipide to Manage Stomatopyrosis10.5005/jp-journals-10024-1972 in Oral Submucous Fibrosis ORIGINAL RESEARCH Rebamipide to Manage Stomatopyrosis in Oral Submucous Fibrosis 1Joanna Baptist, 2Shrijana Shakya, 3Ravikiran Ongole ABSTRACT Source of support: Nil Introduction: Oral submucous fibrosis (OSF) causes progres- Conflict of interest: None sive debilitating symptoms, such as oral burning sensation (sto- matopyrosis) and limited mouth opening. The standard of care INTRODUCTION (SOC) protocol includes habit cessation, intralesional steroid and hyaluronidase injections, and mouth opening exercises. The Oral submucous fibrosis (OSF) is commonly seen in objective of the study was to evaluate efficacy of rebamipide the Indian subcontinent affecting individuals of all age in alleviating burning sensation of the oral mucosa in OSF in groups. It is a potentially malignant disorder caused comparison with SOC intralesional steroid injections. almost exclusively by the use of smokeless form of Materials and methods: Twenty OSF patients were divided into tobacco products. The malignant transformation rates two groups [rebamipide (100 mg TID for 21 days) and betametha- vary from 3 to 19%.1,2 sone (4 mg/mL biweekly for 4 weeks)] of 10 each by random Oral submucous fibrosis causes progressive debilitat- sampling. Burning sensation was assessed every week for 1 month. Burning sensation scores were analyzed using repeated ing symptoms affecting the oral cavity, such as burning measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) and paired t-test. sensation, loss of cheek elasticity, restricted tongue move- Results: Change in burning sensation score was significant ments, and limited mouth opening. Oral submucous (p < 0.05) in the first four visits. However, score between the fibrosis is an irreversible condition and the management 4th and 5th visit was not statistically significant (p > 0.05). -

Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease (Coxsackievirus) Fact Sheet

Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease (Coxsackievirus) Fact Sheet Hand, foot, and mouth disease is caused by one of several types of viruses Hand, foot, and mouth disease is usually characterized by tiny blisters on the inside of the mouth and the palms of the hands, fingers, soles of the feet. It is commonly caused by coxsackievirus A16 (an enterovirus), and less often by other types of viruses. Anyone can get hand, foot, and mouth disease Young children are primarily affected, but it may be seen in adults. Most cases occur in the summer and early fall. Outbreaks may occur among groups of children especially in child care centers or nursery schools. Symptoms usually appear 3 to 5 days after exposure. Hand, foot, and mouth disease is usually spread through person-to-person contact People can spread the disease when they are shedding the virus in their feces. It is also spread by the respiratory tract from mouth or respiratory secretions (such as from saliva on hands or toys). The virus has also been found in the fluid from the skin blisters. The infection is spread most easily during the acute phase/stage of illness when people are feeling ill, but the virus can be spread for several weeks after the onset of infection. The symptoms are much like a common cold with a rash The rash appears as blisters or ulcers in the mouth, on the inner cheeks, gums, sides of the tongue, and as bumps or blisters on the hands, feet, and sometimes other parts of the skin. The skin rash may last for 7 to 10 days. -

Misdiagnosis of Osteosarcoma As Cementoblastoma from an Atypical Mandibular Swelling: a Case Report

ONCOLOGY LETTERS 11: 3761-3765, 2016 Misdiagnosis of osteosarcoma as cementoblastoma from an atypical mandibular swelling: A case report ZAO FANG1*, SHUFANG JIN1*, CHENPING ZHANG1, LIZHEN WANG2 and YUE HE1 1Department of Oral Maxillofacial Head and Neck Oncology, Faculty of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery; 2Department of Oral Pathology, Shanghai Ninth People's Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai Key Laboratory of Stomatology, Shanghai 200011, P.R. China Received December 1, 2014; Accepted January 12, 2016 DOI: 10.3892/ol.2016.4433 Abstract. Cementoblastoma is a form of benign odontogenic of the lesion with extraction of the associated tooth (2); tumor, with the preferred treatment consisting of tooth extrac- however, certain patients may decide against surgery, under- tion and follow-up examinations, while in certain cases, going follow-up alone. Osteosarcoma is a non-hematopoietic, follow-up examinations without surgery are performed. malignant tumor of the bone, with the neoplastic cells of the Osteosarcoma of the jaw is a rare, malignant, mesenchymal lesion producing osteoid (3). This form of tumor is character- tumor, associated with a high mortality rate and low incidence ized by high malignancy, metastasis and mortality rates (4). of metastasis. Cementoblastoma and osteosarcoma of the jaw The tumors are most prevalently located in the metaphyseal are dissimilar in terms of their histological type and prognosis; region of long bones, particularly in the knee and pelvis (5). however, there are a number of covert associations between Osteosarcoma of the jaw is rare, accounting for 5-13% of all them. The present study describes the case of a 20-year-old osteosarcoma cases (6), the majority of which are located in female with an unusual swelling in the left mandible that the mandible. -

High Frequency of Allelic Loss in Dysplastic Lichenoid Lesions

0023-6837/00/8002-233$03.00/0 LABORATORY INVESTIGATION Vol. 80, No. 2, p. 233, 2000 Copyright © 2000 by The United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. Printed in U.S.A. High Frequency of Allelic Loss in Dysplastic Lichenoid Lesions Lewei Zhang, Xing Cheng, Yong-hua Li, Catherine Poh, Tao Zeng, Robert Priddy, John Lovas, Paul Freedman, Tom Daley, and Miriam P. Rosin Faculty of Dentistry (LZ, Y-HL, CP, RP), University of British Columbia, and BC Cancer Research Centre (MPR), Cancer Control Unit, Vancouver, British Columbia, School of Kinesiology (XC, TZ, MPR), Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, British Columbia, Faculty of Dentistry (JL), Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, and Department of Pathology (TD), University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada; and The New York Hospital Medical Center of Queens (PF), Flushing, New York SUMMARY: Oral lichen planus (OLP) is a common mucosal condition that is considered premalignant by some, whereas others argue that only lichenoid lesions with epithelial dysplasia are at risk of progressing into oral carcinoma. A recent study from this laboratory used microsatellite analysis to evaluate OLP for loss of heterozygosity (LOH) at loci on three chromosomal arms (3p, 9p, and 17p) (Am J Path 1997;Vol151:Page323-Page327). Loss on these arms is a common event in oral epithelial dysplasia and has been associated with risk of progression of oral leukoplakia to cancer. The data showed that, although dysplastic epithelium demonstrated a high frequency of LOH (40% for mild dysplasia), a significantly lower frequency of LOH was noted in OLP (6%), which is even lower than that in hyperplasia (14%). -

Study of Oropharyngeal Ulcers with Their Commonest Anatomical Sites of Presentation Correlated with Histopathological Diagnosis Among the North Bengal Population

Panacea Journal of Medical Sciences 2020;10(3):258–263 Content available at: https://www.ipinnovative.com/open-access-journals Panacea Journal of Medical Sciences Journal homepage: www.ipinnovative.com Original Research Article Study of oropharyngeal ulcers with their commonest anatomical sites of presentation correlated with histopathological diagnosis among the north Bengal population Tanwi Ghosal (Sen)1, Pallab Kr Saha2,*, Sauris Sen3 1Dept. of Anatomy, North Bengal Medical College, Sushrutanagar, West Bengal, India 2Dept. of Anatomy, NRS Medical College, Kolkata, West Bengal, India 3Dept. of ENT, Jalpaiguri District Hospital, Jalpaiguri, West Bengal, India ARTICLEINFO ABSTRACT Article history: Introduction: Oropharyngeal ulcers are very common in North East part of India due to bad oral habits like Received 31-07-2020 chewing of tobacco etc. A study was performed at North Bengal Medical College and Hospital among the Accepted 06-10-2020 patients attending otorhinolaryngology outdoor to explore the relationship of different types and proportion Available online 29-12-2020 of oropharyngeal ulcers with their commonest anatomical sites and to elicit the relationship with bad oral habits. Aims: • To elicit the different types and proportions of oropharyngeal ulcers. • To explore the relationship Keywords: of different histopathological types with anatomical sites. • To identify the relationship with addiction. Ulcer Material and Methods: This is a Cross-sectional Observational Hospital based study, conducted in the Oral Cavity Otorhinolaryngology outdoor of North Bengal Medical College and Hospital twice a week. 102 patients Oropharynx were selected as study population after maintaining inclusion and exclusion criteria. Anatomical sites Results: The study shows that the most common type of ulcer is aphthous (25.49%) and the least common types are erythroplakia and autoimmune ulcers (1.96%). -

Oral Lesions in Sjögren's Syndrome

Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2018 Jul 1;23 (4):e391-400. Oral lesions in Sjögren’s syndrome patients Journal section: Oral Medicine and Pathology doi:10.4317/medoral.22286 Publication Types: Review http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.4317/medoral.22286 Oral lesions in Sjögren’s syndrome: A systematic review Julia Serrano 1, Rosa-María López-Pintor 1, José González-Serrano 1, Mónica Fernández-Castro 2, Elisabeth Casañas 1, Gonzalo Hernández 1 1 Department of Oral Medicine and Surgery, School of Dentistry, Complutense University, Madrid, Spain 2 Rheumatology Service, Hospital Infanta Sofía, Madrid, Spain Correspondence: Departamento de Especialidades Clínicas Odontológicas Facultad de Odontología Universidad Complutense de Madrid Plaza Ramón y Cajal s/n, 28040 Madrid. Spain [email protected] Serrano J, López-Pintor RM, González-Serrano J, Fernández-Castro M, Casañas E, Hernández G. Oral lesions in Sjögren’s syndrome: A system- atic review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2018 Jul 1;23 (4):e391-400. Received: 18/11/2017 http://www.medicinaoral.com/medoralfree01/v23i4/medoralv23i4p391.pdf Accepted: 09/05/2018 Article Number: 22291 http://www.medicinaoral.com/ © Medicina Oral S. L. C.I.F. B 96689336 - pISSN 1698-4447 - eISSN: 1698-6946 eMail: [email protected] Indexed in: Science Citation Index Expanded Journal Citation Reports Index Medicus, MEDLINE, PubMed Scopus, Embase and Emcare Indice Médico Español Abstract Background: Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) is an autoimmune disease related to two common symptoms: dry mouth and eyes. Although, xerostomia and hyposialia have been frequently reported in these patients, not many studies have evaluated other oral manifestations. -

Benign Migratory Glossitis: Case Report and Literature Review

Volume 1- Issue 5 : 2017 DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2017.01.000482 Sarfaraz Khan. Biomed J Sci & Tech Res ISSN: 2574-1241 Case Report Open Access Benign Migratory Glossitis: Case Report and Literature Review Sarfaraz Khan1*, Syed AsifHaider Shah2, Tanveer Ahmed Mujahid3 and Muhammad Ishaq4 1Consultant Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon, Pak Field Hospital Darfur, Sudan 2MDC Gujranwala, Pakistan 3Consultant Dermatologist, Pak Field Hospital Darfur, Sudan 4Registrar Dermatologist, Pak Field Hospital Darfur, Sudan Received: October 25, 2017; Published: October 31, 2017 *Corresponding author: Sarfaraz Khan, Consultant Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon, Pakistan Field Hospital Darfur, Sudan, Tel: ; Email: Abstract Benign migratory Glossitis (BMG) is a benign, usually asymptomatic mucosal lesion of dorsal surface of the tongue, characterized by depapillated erythematous patches separated by white irregular borders. Etiology of BMG is unknown. Risk factors include psoriasis, fissured tongue, diabetes mellitus, hypersensitivity and psychological factors. We report BMG in an Egyptian soldier of UN peace keeping force, with stressKeywords: as a possible Geographic etiological tongue; factor Benign and migratory provide literature Glossitis; reviewErythema of this migrans disorder. Introduction Benign migratory Glossitis (BMG) is a benign, immune- spicy/salty food and/or alcoholic drinks [4,5].The lesion typically usually characterized by asymptomatic erythematous patches changes its shape with time owing to the change in pattern of mediated, chronic inflammatory lesion of unknown etiology, depapillation.Similar lesions may also be seen in atrophic candidiasis, local chemical or mechanical trauma, drug induced reactions, psoriasis with whitish margins across the surface of the tongue. This condition is also known as geographic tongue, erythema migrans, Treatment of symptomatic BMG aims at provision of symptomatic Glossitis exfoliativa and wandering rash of the tongue.