Nebraska Architect

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download This

NPS Form 10-900 OMBNo. 1024-0018 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places JUM - C 2005 I Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable". For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Race additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets {NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. 1. Name of Property Historic name Dundee/Happy Hollow Historic District___________________________________ Other names/site number 2. Location Roughly Hamilton on N, JE George & Happy Hollow on W, Street & number Leavenworth on S, 48th on E Not for publication [ ] City or town Omaha Vicinity [] State Nebraska Code NE County Douglas Code 055 Zip code 68132 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this [x] nomination Q request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property [x] meets Q does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

SIAN Vol. 46 No. 1

Volume 46 Winter 2017 Number 1 From Handcraft to High-Tech IA in Northeast Wisconsin ortheast Wisconsin’s Lower Fox River Valley offered The National Railroad Museum in Green Bay was a memorable Fall Tour for the 50 or so SIA mem- host to our Thursday-evening opening reception. We were bers who met up for a three-day event that began greeted by a nice spread of food and drink laid out buffet Non Oct. 27. The Lower Fox River flows northeast- style, but the centers of attention were beautifully restored ward from Lake Winnebago through Appleton, Kaukauna, locomotives and cars, including Union Pacific No. 4017, and De Pere to Green Bay. Our itinerary took us up and down a 4-8-8-4 “Big Boy,” which towered over the reception the valley several times, and extended somewhat beyond area. There was time to take in the exhibits, one of which, the valley along the west shore of Lake Michigan. Process Pullman Porters: From Service to Civil Rights, featured a fully tours ranged from a traditional handcraft cheese factory to furnished 1920s Pullman sleeper. SIA President Maryellen a high-tech maker of computer circuit boards. A series of Russo and SIA Events Coordinator Julie Blair welcomed museums and historic sites featured railroads, canals, automo- participants and explained logistics for the next several biles, papermaking, hydroelectric power, and wood type and days of tours. Julie introduced Candice Mortara, SIA’s local printing machinery. Accommodations were in two boutique coordinator and a member of Friends of the Fox, a not-for- hotels, one with an Irish theme (the St. -

3.0 Affected Environment and Environmental Consequences of the Alternatives

Proposed Ambulatory Care Center FINAL Environmental Assessment NWIHCS Omaha VAMC January 2018 3.0 Affected Environment and Environmental Consequences of the Alternatives This section discusses environmental considerations for the project, the contextual setting of the affected environment, and impacts of the No-Action Alternative and Proposed Action. Aesthetics Definition of the Resource A visual resource is usually defined as an area of unique beauty that is a result of the combined characteristics of the natural aspects of land and human aspects of land use. Wild and scenic rivers, unique topography, and geologic landforms are examples of the natural aspects of land. Examples of human aspects of land use include scenic highways and historic districts. Visual resources can be regulated by management plans, policies, ordinances, and regulations that determine the types of uses that are allowable or protect specially designated or visually sensitive areas. Affected Environment The Omaha VAMC campus is in an urban setting within the City of Omaha. The campus abuts the Field Club golf course and Field Club Trail on the east, the Douglas County Health Department and Health Center to the north, residences of the Morton Meadows neighborhood on the west, and a major retail and commercial corridor along Center Street to the south including the Hanscom Park neighborhood (see Figure 1-2, also see zoning map Figure 3-6). The Omaha VAMC main campus consists of the main hospital building constructed in approximately 1950, various buildings support buildings, surface parking lots, and green space. Environmental Consequences 3.1.3.1 No-Action Alternative Under the No-Action Alternative, the visual aesthetics at the Omaha VAMC would remain unchanged. -

Official Publication of the American Land Title Association

OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE AMERICAN LAND TITLE ASSOCIATION 1876-1976 A Message from the President JANUARY, 1976 With the beginning of each new year, it is incumbent on all of us to evaluate not only our personal achieve ments in our private and business lives but also the achievements of our industry. We can be justly proud of the contributions that the members of the American Land Title Association have made to the real estate in dustry and we should reaffirm our dedication to improving our services for the betterment of the public and the industry. The American Land Title Association seeks to coordinate the efforts of the various state associations and the individual members in promoting public understanding of the value of our services to the public and in the improvement of those services. Many feel that the economic conditions during 1976 will be somewhat better than what we have experi enced in the past few years and we should use this opportunity to increase our activities as an association in those areas which will effectively inform the public and the members of various regulatory bodies of the necessity for and the value of our services. The officers and staff of our Association seek the advice of the membership and, therefore, request and urge that you now plan to attend the Mid-Winter Conference at the Greenbrier in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, on March 21-24, 1976, so that your ideas and wishes can be directly communicated to your officers. On behalf of the officers and staff of the Association, we wish to express our thanks for the helpfulness of the membership and we wish all a very prosperous New Year. -

Papillion Creek Watershed Partnership

NPDES PERMIT (NER220000) FOR SMALL MUNICIPAL STORM SEWER DISCHARGES TO WATERS OF THE STATE LOCATED IN DOUGLAS, SARPY, AND WASHINGTON COUNTIES OF NEBRASKA NPDES PERMIT NUMBER 220003 2019 ANNUAL REPORT Submitted by: City of Papillion, Nebraska 122 East Third Street Papillion, NE 68046 May 2020 City of Papillion 2019 Annual Report May 2020 Permit number NER220003 Report of Certification “I certify under penalty of law that this document and all attachments were prepared under my direction or supervision in accordance with a system designed to assure that qualified personnel properly gathered and evaluated the information submitted. Based on my inquiry of the person or persons who manage the system or those persons directly responsible for gathering the information, the information submitted is to the best of my knowledge and belief, true, accurate, and complete. I am aware that there are significant penalties for submitting false information, including the possibility of fine and imprisonment for known violations. See 18 U.S.C. 1001 and 33 U.S.C 1319, and Neb. Rev. Stat. 81-1508 thru 81-1508.02.” 05/18/2020 Signature of Authorized Representative or Cognizant Official Date Alexander L. Evans, PE Deputy City Engineer Printed Name Title ii City of Papillion 2019 Annual Report May 2020 Permit number NER220003 1. BACKGROUND On July 1, 2017 the Nebraska Department of Environmental Quality (NDEQ) issued a National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit NER210000 for Small Municipal Storm Sewer discharges to waters of the state located in Douglas, Sarpy, and Washington Counties of Nebraska. The co-permittees of the Papillion Creek Watershed Partnership (PCWP) currently authorized to discharge municipal storm water under this permit are Bellevue, Boys Town, Gretna, La Vista, Papillion, Ralston and Sarpy County. -

Atlanta Heritage Trails 2.3 Miles, Easy–Moderate

4th Edition AtlantaAtlanta WalksWalks 4th Edition AtlantaAtlanta WalksWalks A Comprehensive Guide to Walking, Running, and Bicycling the Area’s Scenic and Historic Locales Ren and Helen Davis Published by PEACHTREE PUBLISHERS 1700 Chattahoochee Avenue Atlanta, Georgia 30318-2112 www.peachtree-online.com Copyright © 1988, 1993, 1998, 2003, 2011 by Render S. Davis and Helen E. Davis All photos © 1998, 2003, 2011 by Render S. Davis and Helen E. Davis All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without prior permission of the publisher. This book is a revised edition of Atlanta’s Urban Trails.Vol. 1, City Tours.Vol. 2, Country Tours. Atlanta: Susan Hunter Publishing, 1988. Maps by Twin Studios and XNR Productions Book design by Loraine M. Joyner Cover design by Maureen Withee Composition by Robin Sherman Fourth Edition 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Manufactured in August 2011 in Harrisonburg, Virgina, by RR Donnelley & Sons in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Davis, Ren, 1951- Atlanta walks : a comprehensive guide to walking, running, and bicycling the area’s scenic and historic locales / written by Ren and Helen Davis. -- 4th ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-56145-584-3 (alk. paper) 1. Atlanta (Ga.)--Tours. 2. Atlanta Region (Ga.)--Tours. 3. Walking--Georgia--Atlanta-- Guidebooks. 4. Walking--Georgia--Atlanta Region--Guidebooks. 5. -

DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT Proposed

DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT Proposed Ambulatory Care Center Nebraska-Western Iowa Health Care System Omaha Veterans Affairs Medical Center December 2017 Prepared for: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Nebraska-Western Iowa Health Care System Omaha Veterans Affairs Medical Center 4101 Woolworth avenue, Omaha, NE 68105 Prepared by: Olsson Associates 2111 S. 67th Street, Suite 200 Omaha, NE 68106 Page Intentionally Left Blank Proposed Ambulatory Care Center Environmental Assessment NWIHCS Omaha VAMC December 2017 Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... 1 1.0 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 7 Background ................................................................................................................ 7 Purpose and Need ....................................................................................................11 Space Deficiencies ............................................................................................11 Functional Deficiencies ......................................................................................11 Technical Deficiencies .......................................................................................12 2.0 ACC Alternatives .......................................................................................................14 Alternative 1 – No-Action Alternative ..................................................................14 -

Peoples of the World Ready for Christmas Millions of Persons Around Pilgrims

Becoming Sunny- THEDAILY FINAL Becoming sunny late today. Fair, quite cold tonight. Red Bank, Freehold Long Branch EDITION Cloudy, cold tomorrow. I 7 (Beo Detail!. Paie 2) Monmouth County's Home Newspaper for 92 Years VOL. S3, NO. 126 RED BANK, N. J., WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 24, 1969 28 PAGES 10 CENTS ••••in ••••iiimiiiiiiiiii iiiiiiiiiiniiiiiiiiiiiiiiBniuiiniHiiiiiii Peoples of the World Ready for Christmas Millions of persons around pilgrims. One estimate said er than last year, but many The Vietnam Moratorium the world made last-minute more than 1,000 troops and attributed the increase to Committee took note of the preparations today to cele- police were on duty in the higher prices brought on by holiday theme of peace and brate Christmas. town. inflation rather than addition- scheduled a series of Christ- Although the message of In Vietnam, the allied com- al volume. mas Eve vigils. The observ- the birth of Jesus Christ is mands and the Viet Cong ob- Hundreds of thousands ance in New York includes "Peace on Earth," the wars served cease-fires. Fighting flocked to airports, railroad a candlelight procession to the world had with it last had been at a low level for stations and bus terminals, Central Park with Mayor year remained in Vietnam several weeks, and after the heading home to see rela- John V. Lindsay and other and Nigeria. The Mideast sit- truce began it dropped off tives and families or taking political leaders scheduled to uation remained unsettled. even more. vacations. participate. Three loud explosions rat- Radio Hanoi began broad- Among the travelers will In Europe, the festive sea- tled windows today in Beth- casting recorded messages be President Nixon, his wife son was sneezy with flu but lehem, the birthplace of from American prisoners of and daughter Tricia, who are in full swiTi": French fisher- Christ. -

CHAPTER ONE PRECURSORS of the PASI ORGAN It Is Possible To

CHAPTER ONE PRECURSORS OF THE PASI ORGAN It is possible to consider the historical and situational context of an organ from at least three points of view: (1) the outlook of the organ historian who seeks to understand the place of an instrument in a stylistic stream or movement, (2) the vantage point of an organ builder’s biographer, who attempts to establish the chronology or import of a given instrument within the builder’s entire œuvre, and (3) an eye toward the instrument’s Sitz im Leben, specifically its physical and cultural location. We will set aside for now the first two perspectives, since organologists are only beginning to identify the characteristics of the best of post-Orgelbewegung artisan organ building,1 and a mid-career assessment of organ builder Martin Pasi’s contribution to the art may be equally premature. These stories will surely be written in the future, and will be sufficiently touched upon in the subsequent chapters of this study. The present concern is to portray the historical and cultural context into which Martin Pasi’s Opus 14 has been received. 1 Stephen Bicknell, “Organ Building Today,” in The Cambridge Companion to the Organ, ed. Nicholas Thistlewaite and Geoffrey Webber (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 85-92. 6 Organs of the First and Second Cathedrals Saint Cecilia Cathedral, named for the patron saint of music and musicians, is chronologically the third cathedral of the Archdiocese of Omaha, the Metropolitan See of the Roman Catholic Church in Nebraska.2 Its two nineteenth-century antecedents—and the cultic and cultural activity that flourished in and around them— foreshadowed the pioneering spirit and aspirations of those who would build a great twentieth-century cathedral and a landmark twenty-first century cathedral organ. -

Nomination Form Date Entered DEC I 5 I983 See Instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type All Entries Complete Applicable Sections______1

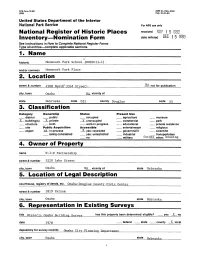

NPS Form 10-900 0MB No.1024-OO18 (3-82) Exp.10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received NQV ! 5 I983 Inventory Nomination Form date entered DEC i 5 I983 See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections___________________________________ 1. Name V historic Monmouth Park School -(D009;ll-l) and/or common Monmouth Park Place 2. Location street & number 4508 Nor-tH^33rd Streef- not for publication city, town Omaha NA vicinity of state Nebraska code 031 county Douglas code 55 3,. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public occupied agriculture museum X building(s) X private X unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object NA in process X yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military future othpr- housing 4. Owner of Property name N-J-D Partnership street & number 3120 Lake Street city, town Omaha NA vicinity of state Nebraska 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Qmaha-Douglas County Civic Center street & number 1819 Farnam city, town Omaha state Nebraska 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title Historic Omaha Building Survey has this property been determined eligible? __ yes X no date 1978 federal __ state __ county X local depository for survey records Qmaha City Planning Department city, town Omaha state Nebraska 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent deteriorated unaltered X original site NA X good ruins X altered moved date . -

N O R Th 24Th Str Eet W a Lk in G to Ur

presents the NORTH 24TH STREET WALKING TOUR STREET WALKING 24TH NORTH North 24th Street is pretty quiet these days. There is a little noise from the barbershops and retail outlets that dot the streetscape. A couple of restau- rants are making a go of it just off the thoroughfare on Lake Street. And there’s a burgeoning arts scene. But the music that once enlivened the area is mostly silent. For blacks who began to reside in North Omaha during the early 20th century, 24th Street became known as the “Street of Dreams.” The area around 24th and Lake Streets emerged as a lively district of music clubs, theaters, restau- rants and retail shops. It Members of the Marching was a haven for enter- Majorettes during a parade passing tainment from the 1920s the intersection of 24th and Lake through the 1960s. in the 1950s. Photo courtesy Great Plains Black History Museum. The street also was important to Jewish settlers, who began to populate the area in the 1890s. They called the stretch of North 24th Street from Cuming to Lake Streets the “Miracle Mile.” Jewish historian Arthur Grossman described the street as “the arterial lifeline connecting homes, shops, and sundry suppliers of products and services necessary for the maintenance of Jewish life.” Blacks, Jews and other ethnicities coexisted peacefully for decades. In 1914, there were 17 grocery stores, five tailors, seven shoe repair shops and five second-hand stores on that stretch of North 24th Street alone, along with confectioners, barbers and butchers. Within four years, 15 of the businesses in the area were owned by blacks, including five restaurants. -

Historical News Rock

Historical News Rock 1898 Year-IN-Review: National News United States Former Senator Trans Blanche K. Bruce Mississippi Annexes The Dies from Diabetes Expositions Hawaii Islands! By Joshua Cunningham World’s Fair By Ikea McGriff The United States officially took Held! ownership of the Hawaiian Islands on July 7. The islands are an important for By Kieara Hunter-Tabb both economic and naval reasons. Held in Omaha, Nebraska starting in The United States had an early interest June 1st there was a World’s Fair. in Hawaii that began in 1820. New This World’s Fair is to show the England missionaries tried in to spread development of the whole West. This their faith. However, a foreign policy World’s Fair started at the Mississippi goal was to keep European powers out River to the Pacific Ocean. of Hawaii. Held in North Omaha, over a 180- The sugar trade acquired true American acre tract stretched, this expo had 21 foothold in Hawaii. The United States classical buildings that had modern government however, provided products from all over in the world. generous terms to Hawaii sugar The Indian Congress was also held. growers and after the Civil War, profits More than 2.6 million people came to began to swell. view the 4,062 exhibits there during The turning point in the United States the four month period of the Exposition. and Hawaiian relationship happened in Former U.S. Senator Blanche K. Bruce died in Washington D.C. on March 17, 1898 of diabetes. He was a former slave. 1890. Congress approved the McKinley Late in 1895 the decision was made tariff, which raised import rates on Bruce’s father, Pettis Perkinson, was a plantation owner and had a to hold the exposition by a small foreign sugar.