Permitted Development Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ACE Committee 6 June 2017 All Papers

Alison Bell Acting Chief Executive Civic Offices, Bridge Street, Reading, RG1 2LU 0118 937 3787 To: Councillor McElligott (Chair); Councillors Eden, Gavin, Hoskin, Jones, Khan, Maskell, McKenna, O’Connell, Our Ref: ace/agenda Pearce, Robinson, Stanford-Beale, Vickers Your Ref: and J Williams. Direct: 0118 937 2332 e-mail:[email protected] 26 May 2017 Your contact is: Richard Woodford – Committee Services NOTICE OF MEETING – ADULT SOCIAL CARE, CHILDREN’S SERVICES AND EDUCATION COMMITTEE – 6 JUNE 2017 A meeting of the Adult Social Care, Children’s Services and Education Committee will be held on Tuesday 6 June 2017 at 6.30pm in the Council Chamber, Civic Offices, Reading. AGENDA WARDS PAGE NO AFFECTED 1. DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST Councillors to declare any disclosable pecuniary interests they may have in relation to the items for consideration. 2. MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF THE ADULT SOCIAL CARE, 1 CHILDREN’S SERVICES AND EDUCATION COMMITTEE HELD ON 20 MARCH 2017 3. MINUTES OF OTHER BODIES – Children’s Trust Partnership Board – 5 April 2017 12 4. PETITIONS Petitions submitted pursuant to Standing Order 36 in - relation to matters falling within the Committee’s Powers & Duties which have been received by Head of Legal & Democratic Services no later than four clear working days before the meeting. CIVIC OFFICES EMERGENCY EVACUATION: If an alarm sounds, leave by the nearest fire exit quickly and calmly and assemble on the corner of Bridge Street and Fobney Street. You will be advised when it is safe to re-enter the building. www.reading.gov.uk | facebook.com/ReadingCouncil | twitter.com/ReadingCouncil 5. -

City of Portsmouth MEMBERS' INFORMATION SERVICE Part 1

City of Portsmouth MEMBERS' INFORMATION SERVICE NO 48 DATE: FRIDAY 4 DECEMBER 2015 The Members' Information Service produced in the Community & Communication Directorate has been prepared in three parts - Part 1 - Decisions by the Cabinet and individual Cabinet Members, subject to Councillors' right to have the matter called in for scrutiny. Part 2 - Proposals from Managers which they would like to implement subject to Councillors' right to have the matter referred to the relevant Cabinet Member or Regulatory Committee; and Part 3 - Items of general information and news. Part 1 - Decisions by the Cabinet The following decisions have been taken by the Cabinet (or individual Cabinet Members), and will be implemented unless the call-in procedure is activated. Rule 15 of the Policy and Review Panels Procedure Rules requires a call-in notice to be signed by any 5 members of the Council. The call-in request must be made to [email protected] and must be received by not later than 5 pm on the date shown in the item. If you want to know more about a proposal, please contact the officer indicated. You can also see the report on the Council's web site at www.portsmouth.gov.uk 1 DATE: FRIDAY 4 DECEMBER 2015 WARD DECISION OFFICER CONTACT 1 Cabinet Member for Traffic & Transportation Decision Meeting - 26 November Joanne Wildsmith Local Democracy Councillor Ellcome as the Cabinet Member has made the following decisions:- Officer Tel: 9283 4057 Eastney & Ferry Road update (Information Item) Pam Turton Craneswater Assistant Head of DECISIONS: Transport & Environment The information report was an update on the previously proposed Traffic Regulation Order (TRO Tel: 9283 4614 36/2015) which has since been withdrawn. -

List of 100 Priority Places

Priority Places Place Lead Authority Argyll and Bute Argyll and Bute Council Barnsley Sheffield City Region Combined Authority Barrow-in-Furness Cumbria County Council Bassetlaw Nottinghamshire County Council Birmingham West Midlands Combined Authority Blackburn with Darwen Blackburn with Darwen Borough Council Blackpool Blackpool Council Blaenau Gwent Blaenau Gwent Council Bolton Greater Manchester Combined Authority Boston Lincolnshire County Council Bradford West Yorkshire Combined Authority Burnley Lancashire County Council Calderdale West Yorkshire Combined Authority Canterbury Kent County Council Carmarthenshire Carmarthenshire Council Ceredigion Ceredigion Council Conwy Conwy County Borough Council Corby Northamptonshire County Council* Cornwall Cornwall Council County Durham Durham County Council Darlington Tees Valley Combined Authority Denbighshire Denbighshire County Council Derbyshire Dales Derbyshire County Council Doncaster Sheffield City Region Combined Authority Dudley West Midlands Combined Authority Dumfries and Galloway Dumfries and Galloway Council East Ayrshire East Ayrshire Council East Lindsey Lincolnshire County Council East Northamptonshire Northamptonshire County Council* Falkirk Falkirk Council Fenland Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Combined Authority Gateshead Gateshead Council Glasgow City Glasgow City Council Gravesham Kent County Council Great Yarmouth Norfolk County Council Gwynedd Gwynedd Council Harlow Essex County Council Hartlepool Tees Valley Combined Authority Hastings East Sussex County Council -

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 Diane ABBOTT MP

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Labour Conservative Diane ABBOTT MP Adam AFRIYIE MP Hackney North and Stoke Windsor Newington Labour Conservative Debbie ABRAHAMS MP Imran AHMAD-KHAN Oldham East and MP Saddleworth Wakefield Conservative Conservative Nigel ADAMS MP Nickie AIKEN MP Selby and Ainsty Cities of London and Westminster Conservative Conservative Bim AFOLAMI MP Peter ALDOUS MP Hitchin and Harpenden Waveney A Labour Labour Rushanara ALI MP Mike AMESBURY MP Bethnal Green and Bow Weaver Vale Labour Conservative Tahir ALI MP Sir David AMESS MP Birmingham, Hall Green Southend West Conservative Labour Lucy ALLAN MP Fleur ANDERSON MP Telford Putney Labour Conservative Dr Rosena ALLIN-KHAN Lee ANDERSON MP MP Ashfield Tooting Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Conservative Conservative Stuart ANDERSON MP Edward ARGAR MP Wolverhampton South Charnwood West Conservative Labour Stuart ANDREW MP Jonathan ASHWORTH Pudsey MP Leicester South Conservative Conservative Caroline ANSELL MP Sarah ATHERTON MP Eastbourne Wrexham Labour Conservative Tonia ANTONIAZZI MP Victoria ATKINS MP Gower Louth and Horncastle B Conservative Conservative Gareth BACON MP Siobhan BAILLIE MP Orpington Stroud Conservative Conservative Richard BACON MP Duncan BAKER MP South Norfolk North Norfolk Conservative Conservative Kemi BADENOCH MP Steve BAKER MP Saffron Walden Wycombe Conservative Conservative Shaun BAILEY MP Harriett BALDWIN MP West Bromwich West West Worcestershire Members of the House of Commons December 2019 B Conservative Conservative -

Local Authority / Combined Authority / STB Members (July 2021)

Local Authority / Combined Authority / STB members (July 2021) 1. Barnet (London Borough) 24. Durham County Council 50. E Northants Council 73. Sunderland City Council 2. Bath & NE Somerset Council 25. East Riding of Yorkshire 51. N. Northants Council 74. Surrey County Council 3. Bedford Borough Council Council 52. Northumberland County 75. Swindon Borough Council 4. Birmingham City Council 26. East Sussex County Council Council 76. Telford & Wrekin Council 5. Bolton Council 27. Essex County Council 53. Nottinghamshire County 77. Torbay Council 6. Bournemouth Christchurch & 28. Gloucestershire County Council 78. Wakefield Metropolitan Poole Council Council 54. Oxfordshire County Council District Council 7. Bracknell Forest Council 29. Hampshire County Council 55. Peterborough City Council 79. Walsall Council 8. Brighton & Hove City Council 30. Herefordshire Council 56. Plymouth City Council 80. Warrington Borough Council 9. Buckinghamshire Council 31. Hertfordshire County Council 57. Portsmouth City Council 81. Warwickshire County Council 10. Cambridgeshire County 32. Hull City Council 58. Reading Borough Council 82. West Berkshire Council Council 33. Isle of Man 59. Rochdale Borough Council 83. West Sussex County Council 11. Central Bedfordshire Council 34. Kent County Council 60. Rutland County Council 84. Wigan Council 12. Cheshire East Council 35. Kirklees Council 61. Salford City Council 85. Wiltshire Council 13. Cheshire West & Chester 36. Lancashire County Council 62. Sandwell Borough Council 86. Wokingham Borough Council Council 37. Leeds City Council 63. Sheffield City Council 14. City of Wolverhampton 38. Leicestershire County Council 64. Shropshire Council Combined Authorities Council 39. Lincolnshire County Council 65. Slough Borough Council • West of England Combined 15. City of York Council 40. -

Q2 1617 LA Referrals

Referrals to Local Authority Adoption Agencies from First4Adoption by region Q2 July-September 2016 Yorkshire & The Humber LA Adoption Agencies North East LA Adoption Agencies Durham County Council 13 North Yorkshire County Council* 30 1 Northumberland County Council 8 Barnsley Adoption Fostering Unit 11 South Tyneside Council 8 Rotherham Metropolitan Borough Council 11 2 North Tyneside Council 5 Bradford Metropolitan Borough Council 10 Redcar Cleveland Borough Council 5 Hull City Council 10 1 Web Referrals Phone Referrals Middlesbrough Council 3 East Riding Of Yorkshire Council 9 City Of Sunderland 2 Cumbria County Council 7 Gateshead Council 2 Calderdale Metropolitan Borough Council 6 1 Newcastle Upon Tyne City Council 2 0 3.5 7 10.5 14 Leeds City Council 6 1 Web Referrals Phone Referrals Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council 5 Hartlepool Borough Council 4 North Lincolnshire Adoption Service 4 1 City Of York Council 3 North East Lincolnshire Adoption Service 3 1 Darlington Borough Council 2 Kirklees Metropolitan Council 2 1 Sheffield Metropolitan City Council 2 Wakefield Metropolitan District Council 2 * Denotes agencies with more than one office entry on the agency finder 0 10 20 30 40 North West LA Adoption Agencies Liverpool City Council 30 Cheshire West And Chester County Council 16 Bolton Metropolitan Borough Council 11 1 Manchester City Council 9 WWISH 9 Lancashire County Council 8 Oldham Council 8 1 Sefton Metropolitan Borough Council 8 2 Web Referrals Phone Referrals Wirral Adoption Team 8 Salford City Council 7 3 Bury Metropolitan -

Parking Services Annual Report 2018/2019

PARKING SERVICES ANNUAL REPORT 2018/2019 Foreword – Councillor Page Welcome to Reading Borough Council’s eleventh Parking Services Annual Report. The report summarises the parking and traffic enforcement responsibilities conducted by the Council in 2018/2019. It also provides details of activities and related financial information. Reading remains a key economic hub in the Thames Valley and wider South-East. Many thousands of people travel into and around Reading on a daily basis, placing great demands on our transport infrastructure. At the same time, local businesses highlight a lack of capacity in transport infrastructure as one of their key concerns, and a restraint to future growth. The increasing demands on infrastructure are seen either through overcrowding or traffic congestion levels. New infrastructure and growing our public transport offer, not only provide significant improvements to sustainable transport options, they support growth in the local economy and reducing Reading’s carbon footprint. The Council introduced its first red route in Reading, along the ‘Purple 17’ bus route in March 2018 to help ease congestion and improve public transport. Reading has an enforcement policy to try and balance the needs of all road users, at a time when demands continue to increase. The key objective is to maintain an appropriate balance between the needs of residents, visitors, businesses and access for disabled people, thereby contributing to the economic growth and success of the town. Enforcement is conducted both on and off-street by Council Parking Services and Civil Enforcement Officers, employed through a term contractor. These officers actively patrol and enforce parking restrictions, supporting traffic management and safety responsibilities imposed on local authorities by legislation, directing patrol efforts to strategically important routes, areas of high contravention and sensitive locations, and in many cases in response to public demand. -

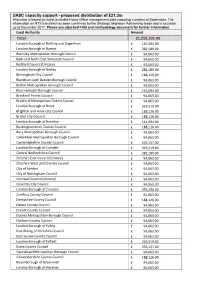

UASC Capacity Support - Proposed Distribution of £21.3M Allocation Is Based on Latest Available Home Office Management Data Capturing Numbers at September

UASC capacity support - proposed distribution of £21.3m Allocation is based on latest available Home Office management data capturing numbers at September. The information on NTS transfers has been confirmed by the Strategic Migration Partnership leads and is accurate up to December 2017. Please see attached FAQ and methodology document for further information. Local Authority Amount Total 21,258,203.00 London Borough of Barking and Dagenham £ 141,094.00 London Borough of Barnet £ 282,189.00 Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council £ 94,063.00 Bath and North East Somerset Council £ 94,063.00 Bedford Council (Unitary) £ 94,063.00 London Borough of Bexley £ 282,189.00 Birmingham City Council £ 188,126.00 Blackburn with Darwen Borough Council £ 94,063.00 Bolton Metropolitan Borough Council £ 94,063.00 Bournemouth Borough Council £ 141,094.00 Bracknell Forest Council £ 94,063.00 Bradford Metropolitan District Council £ 94,063.00 London Borough of Brent £ 329,219.00 Brighton and Hove City Council £ 188,126.00 Bristol City Council £ 188,126.00 London Borough of Bromley £ 141,094.00 Buckinghamshire County Council £ 188,126.00 Bury Metropolitan Borough Council £ 94,063.00 Calderdale Metropolitan Borough Council £ 94,063.00 Cambridgeshire County Council £ 235,157.00 London Borough of Camden £ 329,219.00 Central Bedfordshire Council £ 282,189.00 Cheshire East Council (Unitary) £ 94,063.00 Cheshire West and Chester Council £ 94,063.00 City of London £ 94,063.00 City of Nottingham Council £ 94,063.00 Cornwall Council (Unitary) £ 94,063.00 Coventry City -

Briefing Note Template

Appendix C - Summary of Consultation Responses for Park Lane Primary (Junior School) 1.0 Introduction The following documents are included in this Appendix: • A Letter sent by the School to residents • The School Street residents Consultation Response Summary • A petition signed in support of Park Lane Primary School's School Street Application Page 1 of 11 RESTRICTED 2.0 Letter sent by the School to residents Park Lane Primary School School Road Tilehurst Reading. RG31 5BD Junior Department 0118 937 5515 Infant Department 0118 937 5518 E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Executive Head Teacher Mrs Nicola Browne Dear Local Residents, Re: School Streets Closure Order As a school we are in the process of applying for a School Streets closure on the entrance to Downing Road at drop off and pick up times to school and would like to consult you on this application. Despite our best efforts the traffic from parents at these times is proving an increasing risk to the safety of our children. This closure Order is subject to approval from Reading Borough Council. The closures would only take place during term times at the following times: Day AM School Street Time PM School Street Time Monday 8.30am-8.55am 3.15pm- 3.40pm Tuesday 8.30am-8.55am 3.15pm- 3.40pm Wednesday 8.30am-8.55am 3.15pm- 3.40pm Thursday 8.30am-8.55am 3.15pm- 3.40pm Friday 8.30am-8.55am 3.15pm- 3.40pm The road would be fully closed to entering traffic and points of closure would be marshalled. -

Appendix D STRICTLY CONFIDENTIAL

Appendix D West Berkshire Council Senior Management Review STRICTLY CONFIDENTIAL Prepared for: Nick Carter Chief Executive West Berkshire Council Market Street Newbury RG14 5LD Prepared by: Jennifer McNeill Chartered Fellow CIPD; MA; BEd The Guildhall, High Street Regional Director Winchester, Hampshire, SO23 9GH South East Employers Telephone: 01962 840664 1 e-mail: [email protected] Website: www.seemp.co.uk 29 October 2018 (revised) 2 1. Context and purpose of review 1.1 West Berkshire Council (WBC) is aware that, given the higher age profile of senior managers (many are approaching 60 years of age), a number may retire soon (likely within 2-5 years). Therefore, as part of its workforce and succession planning process, the council seeks to commence early discussions about the current structure and the potential for realignment to meet future service demands and challenges, including scarcer resources and increasing competition in certain areas. 1.2 Workforce planning provides the means to review and redefine the senior manager structure to meet emerging demands and challenges in the medium to longer term. Early consideration can be given to the future shape and structure of the senior management team to meet changing service demands prior to vacancies starting to appear. 1.3 The development of a ‘blue-print’ to take the structure forward will inform decision- making for either a planned process of revising the structure, or to manage vacancies individually as they start to arise. 1.4 The council needs to be able to respond to any skills shortage areas or particular recruitment or retention difficulties. Is the council positioned to attract high level, or difficult to recruit to, skills to fill senior level vacancies when they arise in the short and medium term? 1.5 A planned approach will minimise disruption to service provision in those areas if the situation arises. -

Representations Made on Pre-Submission Draft Local Plan and Proposals Map

REPRESENTATIONS MADE ON PRE-SUBMISSION DRAFT LOCAL PLAN AND PROPOSALS MAP This document contains full copies of the representations made on the Pre- Submission Draft Local Plan and Proposals Map and other supporting documents, as part of the consultation held between 30th November 2017 and 26th January 2018. The representations are shown in this document in alphabetical order. Please use the contents page to navigate, and please note also that page numbers are generally visible on the title page for each representation. For summaries of the representations, set out in document order, please see the Statement of Consultation on the Pre-Submission Local Plan. 1 CONTENTS ALLCOCK, PAUL 5 EBERST, ALAN 207 ANSELL, JULIAN 7 EDEN-JONES, SARAH 210 APPLETON, PATRICIA 14 ELLIS, LIZ 213 ARTHUR HILL – SAVE OUR SWIMMING C.I.C 16 EMMER GREEN RESIDENTS’ ASSOCIATION 219 ASQUITH, DR PETER 19 ENGLEFIELD ESTATE 223 AVIVA LIFE AND PENSIONS 21 ENVIRONMENT AGENCY 229 AYRES, ANNE 27 EVANS, GARY 259 AYRES, ROBERT 29 EVERITT, NICHOLAS 266 B.B.C. 31 FAREY, JULIA AND STEVE 268 BEDFORD, CHRIS 46 F.C.C. ENVIRONMENT 270 BEE, KEVIN 49 FESTIVAL REPUBLIC 274 BELL TOWER COMMUNITY ASSOCIATION 53 FRASER-HARDING, KATHLEEN 288 BERKSHIRE, BUCKINGHAMSHIRE AND OXFORDSHIRE WILDLIFE TRUST 56 FRASER-HARDING, TIM 290 BERKSHIRE GARDENS TRUST 64 GILLOTTS SCHOOL 292 BICKERSTAFFE, JANE 78 GLADMAN DEVELOPMENTS LTD 297 BINGLEY, PATRICK 82 GRASHOFF, ANDREA 326 BISHOP, ROB 84 GRASHOFF, GREGORY 329 BLADES, VICTORIA 89 GREATER LONDON AUTHORITY 335 BOOKER GROUP PLC 92 GREYFRIARS CHURCH 341 -

View Future Day Orals PDF File 0.11 MB

Published: Tuesday 20 April 2021 Questions for oral answer on a future day (Future Day Orals) Questions for oral answer on a future day as of Tuesday 20 April 2021. The order of these questions may be varied in the published call lists. [R] Indicates that a relevant interest has been declared. Questions for Answer on Wednesday 21 April Oral Questions to the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland Patricia Gibson (North Ayrshire and Arran): What recent assessment his Department has made of the effect of the Northern Ireland protocol on levels of trade between Great Britain and Northern Ireland. (914354) Stephen Farry (North Down): What steps the Government is taking to tackle the causes of the recent disorder in Northern Ireland. (914355) Matt Western (Warwick and Leamington): What assessment the Government has made of the potential effect of Budget 2021 on police officer numbers in Northern Ireland. (914356) Kevin Brennan (Cardiff West): What representations he has received from relevant stakeholders on the recent disorder in Northern Ireland. (914359) Rachel Hopkins (Luton South): What comparative assessment he has made of the adequacy of levels of funding for mental health services in Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK. (914363) Geraint Davies (Swansea West): What steps he is taking to increase trade flows between Northern Ireland and Holyhead. (914368) Andrew Gwynne (Denton and Reddish): What steps the Government is taking in response to the recent disorder in Northern Ireland. (914369) Andrew Griffith (Arundel and South Downs): What steps his Department is taking to strengthen Northern Ireland’s place in the UK.