Rising Caste Politics: a Contested Hypothesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MANJUL KRISHNA THAKUR ,Son of Late Pramatha Ranjan Thakur, Fl Aged About 58 Years, Resident of Village & P.O

ANNEXURE IX-C I FORM 26 B ( See Rule 4 A ) BEFORE THE NOTARY PUBLIC : BONGAON AFFIDAVIrT TO BE FURNISHED BY THE CANDIDATE BEFORE THE RETURNING l OFFICER FOR FbE CTION TO WEST BENGAL LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY, FROM bh 97- GAIGHA+A4ABsEMBLY CoNsnIuENcY. Bc1 I, MANJUL KRISHNA THAKUR ,Son of Late Pramatha Ranjan Thakur, fl aged about 58 years, resident of Village & P.o. - Thakurnagar, P.s. - Gaighata, Dist. - North 24 Parganas candidate at the about Election, do hereby solemnly affirm/ state on oath as under :- a 1. I am not accused of any offence (s) punishable with imprisonment for two years or more in a pending case (s)in which a charge (s) her/ have been framed by the court (s) of ' competent jurisdic tion. I] Contd ....... If the deponent is accused of any such offence(s) he shall furnish the following information : CaseIFirst Information report No/ Nos. Not Applicable. Police Station (s) ... Not Applicable. District (s) ..... Not Applicable. State (s) Not Applicable. (iii) Section (s) of the concerned Act (s) and short description of the ofcence (s) for which the condidate has been charged .. Not Applicable. (iv) Court (s)which formed the Charge (s) .. Not Applicable. (v) Date (s) on which the Charge (s) was/ were framed .. Not Applicable. (vi) Whether all or any of the proceeding (s)have been stayed by any Court (s) of Competent Jurisdiction. Not Applicable. 2. I have not been convi cted of an offence (s) other then any offence (s) referred to in sub-section (1) of sub-section (2),or covered in sub-section (3) of Section 8 of the Represen tation of the people Act, 1951 (43 of1951) and sentenced to imprisonment for one year or more. -

The Matua Religious Movement of the 19 and 20

A DOWNTRODDEN SECT AND URGE FOR HUMAN DEVELOPMENT: THE MATUA RELIGIOUS MOVEMENT OF THE 19th AND 20th CENTURY BENGAL, INDIA Manosanta Biswas Santipur College, Kalyani University, Nadia , West Bengal India [email protected] Keywords : Bengal, Caste, Namasudra, Matua Introduction: Anthropologists and Social historians have considered the caste system to be the most unique feature of Indian social organization. The Hindu religious scriptures like Vedas, Puranas, and Smritishatras have recognized caste system which is nonetheless an unequal institution. As per purush hymn, depicted in Rig Veda, the almighty God, the creator of the universe, the Brahma,createdBrahmin from His mouth, Khastriya(the warrior class) from His two hands, Vaishya (the trader class) from His thigh and He created Sudra from His legs.1Among the caste divided Hindus, the Brahmins enjoyed the upper strata of the society and they were entitled to be the religious preacher and teacher of Veda, the Khastriyas were entrusted to govern the state and were apt in the art of warfare, the Vaishyas were mainly in the profession of trading and also in the medical profession, the sudras were at the bottom among the four classes and they were destined to be the servant of the other three classes viz the Brahmins, Khastriya and the Vaishya. The Brahmin priest used to preside over the social and religious festivities of the three classes except that of the Sudras. On the later Vedic period (1000-600 B.C) due to strict imposition of the caste system and intra-caste marriage, the position of different castes became almost hereditary.Marriages made according to the rules of the scriptures were called ‘Anulom Vivaha’ and those held against the intervention of the scriptures were called ‘Pratilom Vivaha’. -

The Journal of Parliamentary Information

The Journal of Parliamentary Information VOLUME LIX NO. 1 MARCH 2013 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI CBS Publishers & Distributors Pvt. Ltd. 24, Ansari Road, Darya Ganj, New Delhi-2 EDITORIAL BOARD Editor : T.K. Viswanathan Secretary-General Lok Sabha Associate Editors : P.K. Misra Joint Secretary Lok Sabha Secretariat Kalpana Sharma Director Lok Sabha Secretariat Assistant Editors : Pulin B. Bhutia Additional Director Lok Sabha Secretariat Parama Chatterjee Joint Director Lok Sabha Secretariat Sanjeev Sachdeva Joint Director Lok Sabha Secretariat © Lok Sabha Secretariat, New Delhi THE JOURNAL OF PARLIAMENTARY INFORMATION VOLUME LIX NO. 1 MARCH 2013 CONTENTS PAGE EDITORIAL NOTE 1 ADDRESSES Addresses at the Inaugural Function of the Seventh Meeting of Women Speakers of Parliament on Gender-Sensitive Parliaments, Central Hall, 3 October 2012 3 ARTICLE 14th Vice-Presidential Election 2012: An Experience— T.K. Viswanathan 12 PARLIAMENTARY EVENTS AND ACTIVITIES Conferences and Symposia 17 Birth Anniversaries of National Leaders 22 Exchange of Parliamentary Delegations 26 Bureau of Parliamentary Studies and Training 28 PARLIAMENTARY AND CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENTS 30 PRIVILEGE ISSUES 43 PROCEDURAL MATTERS 45 DOCUMENTS OF CONSTITUTIONAL AND PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST 49 SESSIONAL REVIEW Lok Sabha 62 Rajya Sabha 75 State Legislatures 83 RECENT LITERATURE OF PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST 85 APPENDICES I. Statement showing the work transacted during the Twelfth Session of the Fifteenth Lok Sabha 91 (iv) iv The Journal of Parliamentary Information II. Statement showing the work transacted during the 227th Session of the Rajya Sabha 94 III. Statement showing the activities of the Legislatures of the States and Union Territories during the period 1 October to 31 December 2012 98 IV. -

Folklore Foundation , Lokaratna ,Volume IV 2011

FOLKLORE FOUNDATION ,LOKARATNA ,VOLUME IV 2011 VOLUME IV 2011 Lokaratna Volume IV tradition of Odisha for a wider readership. Any scholar across the globe interested to contribute on any Lokaratna is the e-journal of the aspect of folklore is welcome. This Folklore Foundation, Orissa, and volume represents the articles on Bhubaneswar. The purpose of the performing arts, gender, culture and journal is to explore the rich cultural education, religious studies. Folklore Foundation President: Sri Sukant Mishra Managing Trustee and Director: Dr M K Mishra Trustee: Sri Sapan K Prusty Trustee: Sri Durga Prasanna Layak Lokaratna is the official journal of the Folklore Foundation, located in Bhubaneswar, Orissa. Lokaratna is a peer-reviewed academic journal in Oriya and English. The objectives of the journal are: To invite writers and scholars to contribute their valuable research papers on any aspect of Odishan Folklore either in English or in Oriya. They should be based on the theory and methodology of folklore research and on empirical studies with substantial field work. To publish seminal articles written by senior scholars on Odia Folklore, making them available from the original sources. To present lives of folklorists, outlining their substantial contribution to Folklore To publish book reviews, field work reports, descriptions of research projects and announcements for seminars and workshops. To present interviews with eminent folklorists in India and abroad. Any new idea that would enrich this folklore research journal is Welcome. -

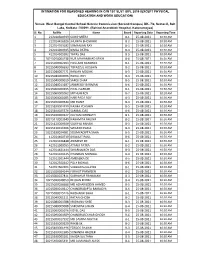

Till 25-08-2021 to 10-09-2021 Untrained Data PDF.Xlsx

INTIMATION FOR REASONED HEARING IN C/W 1ST SLST (UP), 2016 (EXCEPT PHYSICAL EDUCATION AND WORK EDUCATION) Venue: West Bengal Central School Service Commission (Second Campus) DK- 7/2, Sector-II, Salt Lake, Kolkata -700091. (Behind Anandolok Hospital, Karunamoyee) Sl. No. RollNo Name Board Reporting Date Reporting Time 1 212010600939 SUDIP MITRA B-1 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 2 212014416926 JHUMPA BHOWMIK B-2 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 3 212014703182 SOMANJAN RAY B-3 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 4 212014900395 BIMAL PATRA B-4 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 5 412014505992 TAPAS DAS B-5 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 6 10215010004738 NUR MAHAMMAD SEIKH B-6 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 7 10215020002963 POULAMI BANERJEE B-1 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 8 20215040006633 TOFAZZUL HOSSAIN B-2 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 9 20215040007571 RANJAN MODAK B-3 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 10 20215040009006 RAHUL ROY B-4 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 11 20215040009019 SAROJ DHAR B-5 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 12 20215040013187 JANMEJOY BARMAN B-6 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 13 20215060000295 PIYALI SARKAR B-1 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 14 20215060001062 MITHUN ROY B-2 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 15 20215060001085 HARI PADA ROY B-3 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 16 20215070000540 MD HANIF B-4 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 17 20215100004499 NAJMA YEASMIN B-5 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 18 20215100025376 SAMBAL DAS B-6 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 19 20215200000227 KALYANI DEBNATH B-1 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 20 30215110003349 NABAMITA BHUIYA B-2 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 21 30215120009309 SUDIPTA PAHARI B-3 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 22 30215130011566 SWAPAN PARIA B-4 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 23 50215190034681 SOUMYADIPTA SAHA B-5 -

Caste and Mate Selection in Modern India Online Appendix

Marry for What? Caste and Mate Selection in Modern India Online Appendix By Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo, Maitreesh Ghatak and Jeanne Lafortune A. Theoretical Appendix A1. Adding unobserved characteristics This section proves that if exploration is not too costly, what individuals choose to be the set of options they explore reflects their true ordering over observables, even in the presence of an unobservable characteristic they may also care about. Formally, we assume that in addition to the two characteristics already in our model, x and y; there is another (payoff-relevant) characteristic z (such as demand for dowry) not observed by the respondent that may be correlated with x. Is it a problem for our empirical analysis that the decision-maker can make inferences about z from their observation of x? The short answer, which this section briefly explains, is no, as long as the cost of exploration (upon which z is revealed) is low enough. Suppose z 2 fH; Lg with H > L (say, the man is attractive or not). Let us modify the payoff of a woman of caste j and type y who is matched with a man of caste i and type (x; z) to uW (i; j; x; y) = A(j; i)f(x; y)z. Let the conditional probability of z upon observing x, is denoted by p(zjx): Given z is binary, p(Hjx)+ p(Ljx) = 1: In that case, the expected payoff of this woman is: A(j; i)f(x; y)p(Hjx)H + A(j; i)f(x; y)p(Ljx)L: Suppose the choice is between two men of caste i whose characteristics are x0 and x00 with x00 > x0. -

Gééò °Ô{Éséxn Àéöàéçú (Zéé½oééàé) : Àééxéxééòªé

10/29/2018 Fourteenth Loksabha Session : 4 Date : 23-03-2005 Participants : Singh Shri Manvendra,Appadurai Shri M.,Mann Sardar Zora Singh,Sibal Shri Kapil,Krishnaswamy Shri A.,Bhavani Rajenthiran Smt. M.S.K.,Chengara Surendran Shri ,Bellarmin Shri A.V.,Murmu Shri Rupchand,Singh Shri Sitaram,Nishad Shri Mahendra Prasad,Yadav Shri Devendra Prasad,Rawat Shri Bachi Singh,Gowda Dr. (Smt.) Tejasvini,Budholiya Shri Rajnarayan,Singh Shri Ganesh,Sharma Shri Madan Lal,Veerendra Kumar Shri M. P.,Rathod Shri Harisingh Nasaru,Athithan Shri Dhanuskodi,Tripathi Shri Chandramani,Manoj Dr. K.S.,Bhakta Shri Manoranjan,Prabhu Shri R.,Rani Smt. K.,Gao Shri Tapir,Chakraborty Shri Sujan,Mahtab Shri Bhartruhari,Gadhavi Shri Pushpdan Shambhudan,Salim Shri Mohammad,Kusmaria Dr. Ramkrishna,Purandareswari Smt. Daggubati,Singh Ch. Lal,Vijayan Shri A.K.S.,Radhakrishnan Shri Varkala,Yerrannaidu Shri Kinjarapu,Aaron Rashid Shri J.M.,Kumar Shri Shailendra,Meghwal Shri Kailash,Ponnuswamy Shri E.,Selvi Smt. V. Radhika,Mehta Shri Alok Kumar,Khanna Shri Avinash Rai,Prabhu Shri Suresh Title: Discussion regarding natural calamities in the country. 14.52 hrs. DISCUSSION UNDER RULE 193 Re : Natural Calamities in the Country gÉÉÒ °ô{ÉSÉxn àÉÖàÉÇÚ (ZÉɽOÉÉàÉ) : àÉÉxÉxÉÉÒªÉ ={ÉÉvªÉFÉ àÉcÉänªÉ, àÉé +ÉÉ{ɺÉä ¤ÉÆMÉãÉÉ àÉå ¤ÉÉäãÉxÉä BÉEÉÒ <VÉÉVÉiÉ SÉÉciÉÉ cÚÆ* ={ÉÉvªÉFÉ àÉcÉänªÉ : ~ÉÒBÉE cè, ¤ÉÉäÉÊãÉA* *SHRI RUPCHAND MURMU : At the outset I thank you for giving me the opportunity to initiate a discussion on natural calamities under rule 193. Almost every year we talk about drought and flood in this august House. In 1999, there was an oceanic storm in Orissa and in 2001, Gujarat’s Bhuj was struck by an earthquake. -

Provisional Community Profile of Bichitropur, Manikgonj a Basic Sketch of Economic, Social and Political Characteristics of a Remote Rural Site

Provisional Community Profile of Bichitropur, Manikgonj A basic sketch of economic, social and political characteristics of a remote rural site WeD –PROSHIKA, Bangladesh June 2004 1 Report Prepared by Iqbal Alam Khan Nasrin Sultana Mohammed Kamruzzaman Ahmed Borhan Note: This team is grateful to Salim Ahmed Purvez, Sharmin Afroz, Munshi Israil Hossain, Asad Bin Rashid, Nazmun Nahar Lipi, Mahbub Alam, Ms. Sadia Afrin and Dilara Zaman for their various support. 2 Section 1 Introduction to Bichitropur PHYSICAL OVERVIEW OF THE SITE Location Bichitropur is a village under Garpara union in Bichitropur mouja and about 4.5 km to the northwest of the district town of Manikganj. The village has an area of 253 acres (BBS, 1991) and consists of various paras. Infrastructure and Its General attributes The overall, facilities in the village are good as electricity is available all across the village yet avilability of power connection depends on individual household’s financial ability to subscribe for this commodity. Sanitation system is good and all villagers use tube-well for drinking water and almost every household boasts a tube-well. There are two Tara pumps in this village and everyone has access to them. It is also noticeable that most of the tube-wells are affected with iron contamination and some are found to have arsenic contamination. There is a Government-run health complex in the Facilities At a glance: middle part of this village and one private hospital in the eastern part. The government-run • Electricity for the whole village health complex provides for primary health care • Tube well and the private one all kinds of health services • Tara pump including weekly visit by specialist doctors as • One government health complex well as emergency treatment. -

Ranchi to 1580 and That in Seven People Were Found Infect- Fatality Rate Was 1.20 Per Cent

$ 7 " ! * 8 8 8 +,$-+%./0 #&'&'( -. )#*+, : '+"?+;(((# 5+;'+ ,-,+ 25'+";2+ "2'-,')4(3 ;-(+';-);+23+# #+-,#+,)# -+",5+#- 22+#<2=,'@ 4,''+ '2+ A #(+ ,+/ "2-#+") -<"2#+;+"=,>+<3+"+ 9' !*% ++& 6. 9+ 2 !+ 1 .1232.45.26 Q $$%&$ ' R R ) ')4(3 !"# n a serious allegation 23"2'-, Ithat raised the polit- ical temperature in est Bengal's Governor Jagdeep Uttar Pradesh, AAP ! ! WDhankhar, who has been in the and Samajwadi Party news for his frequent run-ins with Chief leaders, in different Minister Mamata Banerjee, has six press conferences, lev- P Officers on Special Duty (OSD) while eled a sensational charge of financial irregular- Rajasthan Governor Kalraj Mishra has ities in land purchase by the Ram Janmabhoomi "! 23"2'-, only one OSD. Trust, which was set up by the Centre for the #$ According to the websites of the dif- construction of the Ram Temple in Ayodhya. ! rime Minister Narendra ferent State Governments, there are four AAP MP Sanjay Singh held a press confer- % ! PModi on Sunday stressed OSD to Bihar Governor and two OSDs ence in Lucknow while former SP MLA and for- ! the need for open and democ- to the Uttar Pradesh (UP) Governor. mer Minister Pawan Pandey addressed reporters ! ! ratic societies to work togeth- ! Similarly, Chhattisgarh and Odisha Bhawan, there is no OSD to Governor in Ayodhya. Ramjanmabhumi Tirth Kshetra er to defend the values they #$ Governors have two OSDs each. Anandiben Patel. There is only one post Trust general secretary Champat Rai said that ! P hold dear and to respond to the The OSD is an officer in the Indian of OSD to Governor in Haryana which they will study the charges of land purchase " increasing global challenges. -

Newsletter Sept

Vol 13 | No. 1 September, October, November 2018 Dear Member, 27th November, 2018 It gives me immense pleasure to connect with you through the BCC&I Newsletter society and the environment in general. The activities of the year ahead will get for the very first time as the President of this historic Institution. At the outset, structured accordingly. may I take this opportunity to convey my seasons greetings and good wishes to you all. With the recent signing of MoU with WEBEL for setting up an incubation centre for startups at Webel Bhavan and special focus on the States MSME sector, your On the macroeconomic level, this year has been sort of a roller coaster ride. In Chamber has its tasks clearly cut out this year. Initiatives aimed at development spite of many debates and discussions, the Indian Economy remained one of the and growth of the States MSME sector to make this sector comparable to the best best performer amongst large economies globally. Teething difficulties in the new in the world are being taken up. To enable successful development of this sector, GST, high and rising real interest rates, an intensifying overhang from the TBS cutting edge technologies should be made available to them and this would call challenge, and sharp falls in certain food prices that impacted agricultural incomes for major skill upgradation. Towards this end a Centre of Excellence for the States are some of the issues confronting the economy. Simmering differences between MSME Sector has been planned by your Chamber in partnership with the Indo- the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and the Central Government over issues of public German Chamber of Commerce to provide expert services and consultation. -

Caste and Mate Selection in Modern India Online Appendix

Marry for What? Caste and Mate Selection in Modern India Online Appendix By Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo, Maitreesh Ghatak and Jeanne Lafortune A. Theoretical Appendix A1. Adding unobserved characteristics This section proves that if exploration is not too costly, what individuals choose to be the set of options they explore reflects their true ordering over observables, even in the presence of an unobservable characteristic they may also care about. Formally, we assume that in addition to the two characteristics already in our model, x and y; there is another (payoff-relevant) characteristic z (such as demand for dowry) not observed by the respondent that may be correlated with x. Is it a problem for our empirical analysis that the decision-maker can make inferences about z from their observation of x? The short answer, which this section briefly explains, is no, as long as the cost of exploration (upon which z is revealed) is low enough. Suppose z 2 fH; Lg with H > L (say, the man is attractive or not). Let us modify the payoff of a woman of caste j and type y who is matched with a man of caste i and type (x; z) to uW (i; j; x; y) = A(j; i)f(x; y)z. Let the conditional probability of z upon observing x, is denoted by p(zjx): Given z is binary, p(Hjx)+ p(Ljx) = 1: In that case, the expected payoff of this woman is: A(j; i)f(x; y)p(Hjx)H + A(j; i)f(x; y)p(Ljx)L: Suppose the choice is between two men of caste i whose characteristics are x0 and x00 with x00 > x0. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission ofof the the copyrightcopyright owner.owner. FurtherFurther reproduction reproduction prohibited prohibited without without permission.