The West Bengal Story

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lok Sabha ___ Synopsis of Debates

LOK SABHA ___ SYNOPSIS OF DEBATES (Proceedings other than Questions & Answers) ______ Monday, March 11, 2013 / Phalguna 20, 1934 (Saka) ______ OBITUARY REFERENCE MADAM SPEAKER: Hon. Members, it is with great sense of anguish and shock that we have learnt of the untimely demise of Mr. Hugo Chavez, President of Venezuela on the 5th March, 2013. Mr. Hugo Chavez was a popular and charismatic leader of Venezuela who always strived for uplifting the underprivileged masses. We cherish our close relationship with Venezuela which was greatly strengthened under the leadership of President Chavez. We deeply mourn the loss of Mr. Hugo Chavez and I am sure the House would join me in conveying our condolences to the bereaved family and the people of Venezuela and in wishing them strength to bear this irreparable loss. We stand by the people of Venezuela in their hour of grief. The Members then stood in silence for a short while. *MATTERS UNDER RULE 377 (i) SHRI ANTO ANTONY laid a statement regarding need to check smuggling of cardamom from neighbouring countries. (ii) SHRI M. KRISHNASSWAMY laid a statement regarding construction of bridge or underpass on NH-45 at Kootterapattu village under Arani Parliamentary constituency in Tamil Nadu. (iii) SHRI RATAN SINGH laid a statement regarding need to set up Breeding Centre for Siberian Cranes in Keoladeo National Park in Bharatpur, Rajasthan. (iv) SHRI P.T. THOMAS laid a statement regarding need to enhance the amount of pension of plantation labourers in the country. (v) SHRI P. VISWANATHAN laid a statement regarding need to set up a Multi Speciality Hospital at Kalpakkam in Tamil Nadu to treat diseases caused by nuclear radiation. -

Pay Uniform Wages — Demand Tea Workers in India (Thousands of Workers Observe 12Th International Tea Day)

Press Release 15 December 2016 Constitute a Wage Board… Pay Uniform Wages — Demand Tea Workers in India (Thousands of Workers observe 12th International Tea Day) “Uniform wages for all tea workers across the country, provided through a wage board” – the demand reverberated in the Raja Bhat tea garden of Kalchini district today, the 15th December 2016, when thousands of tea workers gathered for workers’ assembly as part of the observance of International tea day. The workers from the 22 closed tea estates who struggle to survive without wages or other means of livelihood; and those from the functional tea estates struggling without payment due to the demonetization impact — all participated in the event — to observe their day, air their concerns and urge the government to take immediate steps to avert a colossal humanitarian crisis facing workers and their families. India is second largest tea producing country in the world, with a production of 1233.14 million kgs during the financial year 2015-16. The sector has more than 1.3 million regular workers and an equal number of temporary and non-resident workers, of which more than half of the workers are women. Statistics show growth in tea production and increase in tea export, yet the condition in which the tea workers live are appalling. Ashok Ghosh, International Tea Day Convener and West Bengal General Secretary of United Trades Union Congress says: Demonetization cannot weaken our spirits in coming together for raising our concerns. Fighting all odds, we observed ITD, since it is the day to voice our rights”. ITD observance in Kalchini district has become quite apt now, Says Manohar Tirkey, ex MP from Alipurduar constituency. -

MANJUL KRISHNA THAKUR ,Son of Late Pramatha Ranjan Thakur, Fl Aged About 58 Years, Resident of Village & P.O

ANNEXURE IX-C I FORM 26 B ( See Rule 4 A ) BEFORE THE NOTARY PUBLIC : BONGAON AFFIDAVIrT TO BE FURNISHED BY THE CANDIDATE BEFORE THE RETURNING l OFFICER FOR FbE CTION TO WEST BENGAL LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY, FROM bh 97- GAIGHA+A4ABsEMBLY CoNsnIuENcY. Bc1 I, MANJUL KRISHNA THAKUR ,Son of Late Pramatha Ranjan Thakur, fl aged about 58 years, resident of Village & P.o. - Thakurnagar, P.s. - Gaighata, Dist. - North 24 Parganas candidate at the about Election, do hereby solemnly affirm/ state on oath as under :- a 1. I am not accused of any offence (s) punishable with imprisonment for two years or more in a pending case (s)in which a charge (s) her/ have been framed by the court (s) of ' competent jurisdic tion. I] Contd ....... If the deponent is accused of any such offence(s) he shall furnish the following information : CaseIFirst Information report No/ Nos. Not Applicable. Police Station (s) ... Not Applicable. District (s) ..... Not Applicable. State (s) Not Applicable. (iii) Section (s) of the concerned Act (s) and short description of the ofcence (s) for which the condidate has been charged .. Not Applicable. (iv) Court (s)which formed the Charge (s) .. Not Applicable. (v) Date (s) on which the Charge (s) was/ were framed .. Not Applicable. (vi) Whether all or any of the proceeding (s)have been stayed by any Court (s) of Competent Jurisdiction. Not Applicable. 2. I have not been convi cted of an offence (s) other then any offence (s) referred to in sub-section (1) of sub-section (2),or covered in sub-section (3) of Section 8 of the Represen tation of the people Act, 1951 (43 of1951) and sentenced to imprisonment for one year or more. -

List of Successful Candidates

11 - LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES CONSTITUENCY WINNER PARTY Andhra Pradesh 1 Nagarkurnool Dr. Manda Jagannath INC 2 Nalgonda Gutha Sukender Reddy INC 3 Bhongir Komatireddy Raj Gopal Reddy INC 4 Warangal Rajaiah Siricilla INC 5 Mahabubabad P. Balram INC 6 Khammam Nama Nageswara Rao TDP 7 Aruku Kishore Chandra Suryanarayana INC Deo Vyricherla 8 Srikakulam Killi Krupa Rani INC 9 Vizianagaram Jhansi Lakshmi Botcha INC 10 Visakhapatnam Daggubati Purandeswari INC 11 Anakapalli Sabbam Hari INC 12 Kakinada M.M.Pallamraju INC 13 Amalapuram G.V.Harsha Kumar INC 14 Rajahmundry Aruna Kumar Vundavalli INC 15 Narsapuram Bapiraju Kanumuru INC 16 Eluru Kavuri Sambasiva Rao INC 17 Machilipatnam Konakalla Narayana Rao TDP 18 Vijayawada Lagadapati Raja Gopal INC 19 Guntur Rayapati Sambasiva Rao INC 20 Narasaraopet Modugula Venugopala Reddy TDP 21 Bapatla Panabaka Lakshmi INC 22 Ongole Magunta Srinivasulu Reddy INC 23 Nandyal S.P.Y.Reddy INC 24 Kurnool Kotla Jaya Surya Prakash Reddy INC 25 Anantapur Anantha Venkata Rami Reddy INC 26 Hindupur Kristappa Nimmala TDP 27 Kadapa Y.S. Jagan Mohan Reddy INC 28 Nellore Mekapati Rajamohan Reddy INC 29 Tirupati Chinta Mohan INC 30 Rajampet Annayyagari Sai Prathap INC 31 Chittoor Naramalli Sivaprasad TDP 32 Adilabad Rathod Ramesh TDP 33 Peddapalle Dr.G.Vivekanand INC 34 Karimnagar Ponnam Prabhakar INC 35 Nizamabad Madhu Yaskhi Goud INC 36 Zahirabad Suresh Kumar Shetkar INC 37 Medak Vijaya Shanthi .M TRS 38 Malkajgiri Sarvey Sathyanarayana INC 39 Secundrabad Anjan Kumar Yadav M INC 40 Hyderabad Asaduddin Owaisi AIMIM 41 Chelvella Jaipal Reddy Sudini INC 1 GENERAL ELECTIONS,INDIA 2009 LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATE CONSTITUENCY WINNER PARTY Andhra Pradesh 42 Mahbubnagar K. -

The Journal of Parliamentary Information

The Journal of Parliamentary Information VOLUME LIX NO. 1 MARCH 2013 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI CBS Publishers & Distributors Pvt. Ltd. 24, Ansari Road, Darya Ganj, New Delhi-2 EDITORIAL BOARD Editor : T.K. Viswanathan Secretary-General Lok Sabha Associate Editors : P.K. Misra Joint Secretary Lok Sabha Secretariat Kalpana Sharma Director Lok Sabha Secretariat Assistant Editors : Pulin B. Bhutia Additional Director Lok Sabha Secretariat Parama Chatterjee Joint Director Lok Sabha Secretariat Sanjeev Sachdeva Joint Director Lok Sabha Secretariat © Lok Sabha Secretariat, New Delhi THE JOURNAL OF PARLIAMENTARY INFORMATION VOLUME LIX NO. 1 MARCH 2013 CONTENTS PAGE EDITORIAL NOTE 1 ADDRESSES Addresses at the Inaugural Function of the Seventh Meeting of Women Speakers of Parliament on Gender-Sensitive Parliaments, Central Hall, 3 October 2012 3 ARTICLE 14th Vice-Presidential Election 2012: An Experience— T.K. Viswanathan 12 PARLIAMENTARY EVENTS AND ACTIVITIES Conferences and Symposia 17 Birth Anniversaries of National Leaders 22 Exchange of Parliamentary Delegations 26 Bureau of Parliamentary Studies and Training 28 PARLIAMENTARY AND CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENTS 30 PRIVILEGE ISSUES 43 PROCEDURAL MATTERS 45 DOCUMENTS OF CONSTITUTIONAL AND PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST 49 SESSIONAL REVIEW Lok Sabha 62 Rajya Sabha 75 State Legislatures 83 RECENT LITERATURE OF PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST 85 APPENDICES I. Statement showing the work transacted during the Twelfth Session of the Fifteenth Lok Sabha 91 (iv) iv The Journal of Parliamentary Information II. Statement showing the work transacted during the 227th Session of the Rajya Sabha 94 III. Statement showing the activities of the Legislatures of the States and Union Territories during the period 1 October to 31 December 2012 98 IV. -

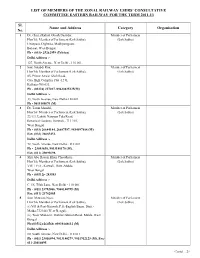

List of Members of the Zonal Railway Users’ Consultative Committee Eastern Railway for the Term 2011-13

LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE ZONAL RAILWAY USERS’ CONSULTATIVE COMMITTEE EASTERN RAILWAY FOR THE TERM 2011-13 Sl. Name and Address Category Organisation No. 1 Dr. (Smt.) Kakoli Ghosh Dastidar, Member of Parliament Hon’ble Member of Parliament (Lok Sabha), (Lok Sabha) Uttarpara, Digberia, Madhyamgram, Barasat, West Bengal. Ph - (033)- 25262959 (Telefax) Delhi Address :- 127, North Avenue, New Delhi - 110 001. 2 Smt. Satabdi Roy, Member of Parliament Hon’ble Member of Parliament (Lok Sabha), (Lok Sabha) 85, Prince Anwar Shah Road, City High Complex Flat -12 G, Kolkata-700 033. Ph - (03324) 227017, 09433025125(M) Delhi Address :- 33, North Avenue, New Delhi-110 001. Ph - 9013180070 (M) 3 Dr. Tarun Mandal, Member of Parliament Hon’ble Member of Parliament (Lok Sabha), (Lok Sabha) 22/1/3, Lakshi Narayan Tala Road, Botanical Gardens, Howrah - 711 103, West Bengal. Ph - (033) 26684184, 26687597, 9434097888 (M) Fax. (033) 26685451. Delhi Address :- 72, North Avenue, New Delhi - 110 001. Ph - 23093658, 9013180170 (M), Fax. (011) 23093698. 4 Shri Abu Hasem Khan Choudhury, Member of Parliament Hon’ble Member of Parliament (Lok Sabha), (Lok Sabha) Vill + P.O - Kotwali, Distt.-Malda, West Bengal. Ph - (03512)- 283593 Delhi Address :- C 1/6, Tilak Lane, New Delhi - 110 001. Ph - (011) 23782066, 9868180995 (M) Fax. (011) 23782065 5 Smt. Mausam Noor, Member of Parliament Hon’ble Member of Parliament (Lok Sabha), (Lok Sabha) (i) Vill & Post-Kotwali, P.S.-English Bazar, Distt.- Malda-732144 (West Bengal). (ii) 'Noor Mansion', Rathlari Station Road, Malda, West Bengal. Ph-(03512)-264560, 09830448612 (M) Delhi Address :- 80, South Avenue, New Delhi - 110 011. -

Condition of the Major Migrant Tribes of Jalpaiguri District: a Historical Survey Over the Last Hundred Years (1901-2000 A.D.)

International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Development www.allsubjectjournal.com Online ISSN: 2349-4182, Print ISSN: 2349-5979, Impact Factor: RJIF 5.72 Received: 04-02-2021, Accepted: 27-02-2021, Published: 31-03-2021 Volume 8, Issue 3, 2021, Page No. 119-124 Condition of the major migrant tribes of Jalpaiguri District: A historical survey over the last hundred years (1901-2000 A.D.) Manadev Roy Assistant Professor of History, Kurseong College (Affiliated to North Bengal University) Darjeeling, West Bengal, India Abstract After the formation of Jalpaiguri district in 1869 the British Government selected the district as a centre of Tea Industry in India. Many migrant tribes namely the Santhals, Mundas, Oraons, Malpahari, Chikboraik etc., came to the district following by the tea industry. But at the beginning of their settlement the tribal workers could not come out from the boundary of the tea gardens. These gardens were seemed like isolated islands. They were physically and mentally tortured by various authorities of tea gardens, money lenders, and land lords etc. In the tea gardens tribal labourers lost their lives affected with black water fever, malaria, dengue, cholera etc. as medical facility was not good. The tribal children did not have the choice to study in their mother tongue. In school they had to study either in Bengali, Hindi or Nepali medium. In Jalpaiguri district, the subsistence economy forced the tribal men and women and their children into manual work. In the post-colonial period the migrant tribes were fully divided into two groups e.g., the Christian and non-Christian. -

List of Winning Candidated Final for 16Th

Leading/Winning State PC No PC Name Candidate Leading/Winning Party Andhra Pradesh 1 Adilabad Rathod Ramesh Telugu Desam Andhra Pradesh 2 Peddapalle Dr.G.Vivekanand Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 3 Karimnagar Ponnam Prabhakar Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 4 Nizamabad Madhu Yaskhi Goud Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 5 Zahirabad Suresh Kumar Shetkar Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 6 Medak Vijaya Shanthi .M Telangana Rashtra Samithi Andhra Pradesh 7 Malkajgiri Sarvey Sathyanarayana Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 8 Secundrabad Anjan Kumar Yadav M Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 9 Hyderabad Asaduddin Owaisi All India Majlis-E-Ittehadul Muslimeen Andhra Pradesh 10 Chelvella Jaipal Reddy Sudini Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 11 Mahbubnagar K. Chandrasekhar Rao Telangana Rashtra Samithi Andhra Pradesh 12 Nagarkurnool Dr. Manda Jagannath Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 13 Nalgonda Gutha Sukender Reddy Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 14 Bhongir Komatireddy Raj Gopal Reddy Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 15 Warangal Rajaiah Siricilla Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 16 Mahabubabad P. Balram Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 17 Khammam Nama Nageswara Rao Telugu Desam Kishore Chandra Suryanarayana Andhra Pradesh 18 Aruku Deo Vyricherla Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 19 Srikakulam Killi Krupa Rani Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 20 Vizianagaram Jhansi Lakshmi Botcha Indian National Congress Andhra Pradesh 21 Visakhapatnam Daggubati Purandeswari -

Parliamentary Bulletin

RAJYA SABHA Parliamentary Bulletin PART-II Nos.: 51236-51237] WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 4, 2013 No. 51236 Committee Co-ordination Section Meeting of the Parliamentary Forum on Youth As intimated by the Lok Sabha Secretariat, a meeting of the Parliamentary Forum on Youth on the subject ‘Youth and Social Media: Challenges and Opportunities’ will be held on Thursday, 05 September, 2013 at 1530 hrs. in Committee Room No.074, Ground Floor, Parliament Library Building, New Delhi. Shri Naman Pugalia, Public Affairs Analyst, Google India will make a presentation. 2. Members are requested to kindly make it convenient to attend the meeting. ——— No. 51237 Committee Co-ordination Section Re-constitution of the Department-related Parliamentary Standing Committees (2013-2014) The Department–related Parliamentary Standing Committees have been reconstituted w.e.f. 31st August, 2013 as follows: - Committee on Commerce RAJYA SABHA 1. Shri Birendra Prasad Baishya 2. Shri K.N. Balagopal 3. Shri P. Bhattacharya 4. Shri Shadi Lal Batra 2 5. Shri Vijay Jawaharlal Darda 6. Shri Prem Chand Gupta 7. Shri Ishwarlal Shankarlal Jain 8. Shri Shanta Kumar 9. Dr. Vijay Mallya 10. Shri Rangasayee Ramakrishna LOK SABHA 11. Shri J.P. Agarwal 12. Shri G.S. Basavaraj 13. Shri Kuldeep Bishnoi 14. Shri C.M. Chang 15. Shri Jayant Chaudhary 16. Shri K.P. Dhanapalan 17. Shri Shivaram Gouda 18. Shri Sk. Saidul Haque 19. Shri S. R. Jeyadurai 20. Shri Nalin Kumar Kateel 21. Shrimati Putul Kumari 22. Shri P. Lingam 23. Shri Baijayant ‘Jay’ Panda 24. Shri Kadir Rana 25. Shri Nama Nageswara Rao 26. Shri Vishnu Dev Sai 27. -

Gaighata Assembly West Bengal Factbook

Editor & Director Dr. R.K. Thukral Research Editor Dr. Shafeeq Rahman Compiled, Researched and Published by Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. D-100, 1st Floor, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-I, New Delhi- 110020. Ph.: 91-11- 43580781, 26810964-65-66 Email : [email protected] Website : www.electionsinindia.com Online Book Store : www.datanetindia-ebooks.com Report No. : AFB/WB-097-0619 ISBN : 978-93-5293-647-2 First Edition : January, 2018 Third Updated Edition : June, 2019 Price : Rs. 11500/- US$ 310 © Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical photocopying, photographing, scanning, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. Please refer to Disclaimer at page no. 166 for the use of this publication. Printed in India No. Particulars Page No. Introduction 1 Assembly Constituency at a Glance | Features of Assembly as per 1-2 Delimitation Commission of India (2008) Location and Political Maps 2 Location Map | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency in District | Boundaries 3-9 of Assembly Constituency under Parliamentary Constituency | Town & Village-wise Winner Parties- 2019, 2016, 2014, 2011 and 2009 Administrative Setup 3 District | Sub-district | Towns | Villages | Inhabited Villages | Uninhabited 10-13 Villages | Village Panchayat | Intermediate Panchayat Demographics 4 Population | Households | Rural/Urban Population | Towns and Villages by 14-15 Population Size | Sex Ratio (Total -

Public Relations Directory of Govt. of West Bengal

PUBLIC RELATIONS DIRECTORY OF GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL WEST BENGAL INFORMATION AND CULTURAL CENTRE DEPARTMENT OF INFORMATION AND CULTURAL AFFAIRS GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL 18 and 19, Bhai Vir Singh Marg, New Delhi-110001 Website: http://wbicc.in Office of the Principal Resident Commissioner and Manjusha PUBLIC RELATIONS DIRECTORY Prepared and Compiled by West Bengal Information and Cultural Centre New Delhi Foreword We are delighted to bring out a Public Relations Directory from the West Bengal Information & Cultural Centre Delhi collating information, considered relevant, at one place. Against the backdrop of the new website of the Information Centre (http://wbicc.in) launched on 5th May, 2011 and a daily compilation of news relating to West Bengal on the Webpage Media Reflections (www.wbmediareflections.in) on 12th September, 2011, this is another pioneering effort of the Centre in releasing more information under the public domain. A soft copy of the directory with periodic updates will also be available on the site http://wbicc.in. We seek your comments and suggestions to keep the information profile upto date and user-friendly. Please stay connected (Bhaskar Khulbe) Pr. Resident Commissioner THE STATE AT A GLANCE: ● Number of districts: 18 (excluding Kolkata) ● Area: 88,752 sq. km. ● No. of Blocks : 341 ● No. of Towns : 909 ● No. of Villages : 40,203 ● Total population: 91,347,736 (as in 2011 Census) ● Males: 46,927,389 ● Females: 44,420,347 ● Decadal population growth 2001-2011: 13.93 per cent ● Population density: 1029 persons per sq. km ● Sex ratio: 947 ● Literacy Rate: 77.08 per cent Males: 82.67 per cent Females: 71.16 per cent Information Directory of West Bengal Goverment 2. -

JPI March 2015.Pdf

The Journal of Parliamentary Information VOLUME LXI NO. 1 MARCH 2015 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI CBS Publishers & Distributors Pvt. Ltd. 24, Ansari Road, Darya Ganj, New Delhi-2 EDITORIAL BOARD Editor : Anoop Mishra Secretary-General Lok Sabha Associate Editors : D. Bhalla Secretary Lok Sabha Secretariat P.K. Misra Additional Secretary Lok Sabha Secretariat Sayed Kafil Ahmed Director Lok Sabha Secretariat Assistant Editors : Pulin B. Bhutia Additional Director Lok Sabha Secretariat Sanjeev Sachdeva Joint Director Lok Sabha Secretariat V. Thomas Ngaihte Joint Director Lok Sabha Secretariat © Lok Sabha Secretariat, New Delhi THE JOURNAL OF PARLIAMENTARY INFORMATION VOLUME LXI NO. 1 MARCH 2015 CONTENTS PAGE EDITORIAL NOTE 1 PARLIAMENTARY EVENTS AND ACTIVITIES Conferences and Symposia 3 Birth Anniversaries of National Leaders 4 Exchange of Parliamentary Delegations 8 Parliament Museum 9 Bureau of Parliamentary Studies and Training 9 PRIVILEGE ISSUES 11 PROCEDURAL MATTERS 13 PARLIAMENTARY AND CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENTS 15 DOCUMENTS OF CONSTITUTIONAL AND PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST 27 SESSIONAL REVIEW Lok Sabha 41 Rajya Sabha 56 State Legislatures 72 RECENT LITERATURE OF PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST 74 APPENDICES I. Statement showing the work transacted during the Third Session of the Sixteenth Lok Sabha 82 II. Statement showing the work transacted during the 233rd Session of the Rajya Sabha 86 III. Statement showing the activities of the Legislatures of the States and Union Territories during the period 1 October to 31 December 2014 91 (iv) iv The Journal of Parliamentary Information IV. List of Bills passed by the Houses of Parliament and assented to by the President during the period 1 October to 31 December 2014 97 V.