Exploring the Motivations and Experiences of Visitors to a 'Lighter'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CONFIDENTIAL INFORMATION MEMORANDUM £2,729,000,000 Senior Secured Credit Facilities

October 2019 Motion Acquisition Limited October 2019 Motion Acquisition Limited CONFIDENTIAL INFORMATION MEMORANDUM £2,729,000,000 Senior Secured Credit Facilities £400,000,000 Revolving Credit Facility £2,329,000,000 Term Loan B Facility Joint Global Coordinators: Joint Lead Arrangers and Joint Bookrunners: Mandated Lead Arrangers: SPECIAL NOTICE REGARDING PUBLICLY AVAILABLE INFORMATION MOTION ACQUISITION LIMITED (THE “COMPANY”) HAS REPRESENTED THAT THE INFORMATION CONTAINED IN THIS CONFIDENTIAL INFORMATION MEMORANDUM IS EITHER PUBLICLY AVAILABLE OR DOES NOT CONSTITUTE MATERIAL NON-PUBLIC INFORMATION WITH RESPECT TO THE COMPANY OR ITS SECURITIES. THE RECIPIENT OF THIS CONFIDENTIAL INFORMATION MEMORANDUM HAS STATED THAT IT DOES NOT WISH TO RECEIVE MATERIAL NON- PUBLIC INFORMATION WITH RESPECT TO THE COMPANY AND/OR MERLIN ENTERTAINMENTS PLC (THE “TARGET” AND TOGETHER WITH ITS SUBSIDIARIES, THE “TARGET GROUP”) AND/OR THEIR RESPECTIVE AFFILIATES OR THEIR RESPECTIVE SECURITIES AND ACKNOWLEDGES THAT OTHER LENDERS HAVE RECEIVED A CONFIDENTIAL INFORMATION MEMORANDUM THAT CONTAINS ADDITIONAL INFORMATION WITH RESPECT TO SUCH PERSONS OR THEIR RESPECTIVE SECURITIES THAT MAY BE MATERIAL. NEITHER THE COMPANY NOR THE ARRANGERS TAKE ANY RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE RECIPIENT’S DECISION TO LIMIT THE SCOPE OF THE INFORMATION IT HAS OBTAINED IN CONNECTION WITH ITS EVALUATION OF THE COMPANY, THE TARGET GROUP AND THE FACILITIES. NOTWITHSTANDING THE RECIPIENT’S DESIRE TO ABSTAIN FROM RECEIVING MATERIAL NON-PUBLIC INFORMATION WITH RESPECT TO THE COMPANY AND THE -

2019 Tier 1 Corporate Document December 2019 - Issued 28/11/2019

2019 Tier 1 Corporate Document December 2019 - Issued 28/11/2019 2019 Tier 1 Corporate Document December 2019 - Issued 28/11/2019 Please remember that the Merlin Attractions discounted rates should only be listed within staff / members area of your website or intranet and the discounted tickets are for staff / members personal use only. The discounts or logos should not be listed in any form on social media or public facing websites and are not for re-sale. 2019 Tier 1 Corporate Document December 2019 - Issued 28/11/2019 The Merlin Entertainments Group have populated the To access your exclusive tickets, click the relevant link, if required, stores already with the relevant products for your offer, log into the site with the username and password provided. please find below a step by step process for purchasing and printing tickets; Please note that individual tickets are non-refundable and non- exchangeable. 1. Log into store using credentials supplied. This offer is for personal use only to enable you to book tickets for your family and friends when visiting the attraction together. 2. Your discounted tickets will be displayed- add the tickets you require to your basket selecting your chosen date and The sharing of the offer details, may result in this offer being time. terminated and action being taken. 3. Choose if you would like to collect your tickets at the Proof of company employment/membership may be requested on attraction or a print@home/mobile ticket. arrival. 4. Proceed to check out to confirm your booking and make payment using a credit/debit card or Paypal account. -

Creating a Theme Park

CREATING A THEME PARK HOME SCHOOLING RESOURCES PACK Designed and created by J. Gray (Key Stage 2 Teacher) for Merlin Annual Pass and Merlin Magic Making. © Merlin Entertainments 2021 WELCOME PARENT/CARER NOTES Dear Parents/Carers, Welcome to our ‘Creating a Theme Park’ Home Schooling Resources Pack. These resources have been especially created with Key Stage 2 children in mind but can be enjoyed by adults and children alike during these difficult times. This pack will place you at the heart of Merlin Magic Making (MMM), our in-house creative and project delivery team, as children set out to create their own imaginary theme park within the United Kingdom through 4 key approaches; Finding, Creating, Producing and Delivering the Magic. The worksheets contained within this pack will guide you through each stage, providing you and your family with hours of fun! We would love to see some of your work, so don’t forget to tag us on social media using the hashtag #MagicMakingPack. Keep safe! Merlin Annual Pass Designed and created by J. Gray (Key Stage 2 Teacher) for Merlin Annual Pass and Merlin Magic Making. © Merlin Entertainments 2021 INDEX 1. FINDING THE MAGIC A. PLOTTING THE LOCATIONS OF UK CITIES ON A MAP B. PLOTTING MERLIN ATTRACTIONS ON A MAP C. RESEARCHING UK CITIES D. COMPARING SIMILARITIES AND DIFFERENCES 2. CREATING THE MAGIC A. RESEARCHING IMAGINARY WORLDS B. CREATING AN IMAGINARY WORLD C. WRITING ABOUT YOUR IMAGINARY WORLD D. DESIGNING YOUR THEME PARK’S LOGO E. DESIGNING YOUR THEME PARK’S UNIFORM 3. PRODUCING THE MAGIC A. BUILDING YOUR PARK 4. -

The Traditional Yet Unexpected Cuisine of Michele Mazza the Chef

PERLA LICHI DESIGN REDEFINING DESIGN WITH FINE ART YESTERDAY, TODAY & TOMORROW Enroll Now CONTEMPORARY Showroom PROFESSIONAL INTERIOR DESIGN | 3304 North East 33rd Street Fort Lauderdale 33308 CORPORATE Headquarters 7381 W Sample Rd Coral Springs FL 33065 polaroiduniversity.com FURNISHINGS | INSTALLATION perlalichi.com | Tel 954-726-0899 FL ID #1727 THE AFTER AFTER PARTY AMPLIFIED ACCOMMODATIONS ICONIC ENTERTAINMENT ENDLESS SURPRISES HARDROCKHOLLY.COM 2 Opulence Spring 2018 Spring 2018 Opulence 3 Experience the before and after ©2017 California Closet Company, Inc. All rights reserved. Each franchise independently owned and operated. Each franchise All rights reserved. Inc. ©2017 California Closet Company, See more stories #CCBeforeAfter californiaclosets.com 305.623.8282 MIAMI 900 Park Centre Blvd. FL098_Opulence_Sp Couple 18x11.9_0517.indd 1 5/17/17 9:41 AM ASTONISHING 233 South Federal Highway, Boca Raton, Florida • Tel: 561.477.5444 BOCA RATON | NEW YORK | LOS ANGELES | CHICAGO | DALLAS | GENEVA | LONDON | HONG KONG | TEL AVIV | DUBAI | PANAMA | MOSCOW International YOU DREAM IT, WE FIND IT, YOU CHARTER IT WINTER 2017/18 You’re invited to a modern luxury experience. Luxury was always meant to be playful. Experience it free from restriction with a new iconic timepiece every three months. This is Eleven James. This is permission to play. Discover more at elevenjames.com or call 855-ELEVEN-J 8 Opulence Winter 2017/18 International 52 JD MILLER FEATURES CONTINUED 55 DINE LIKE A TUSCAN 28 NORMAN VAN AKEN’S 1921 UPPERCLASSMAN Forte dei Marmi, helmed CULINARY MASTERPIECE James Beard Awarded Chef by Two-Michelin Star Chef Norman Van Aken merges Antonio Mellino, brings fine art with his renowned cuisine authentic Italian fare to the United States. -

Thesis Title

Death, Dying and Dark Tourism in Contemporary Society: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis by Philip R.Stone A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment for the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Central Lancashire October 2010 Student Declaration I declare that while registered as a candidate for the research degree, I have not been a registered candidate or enrolled student for another award of the University or other academic or professional institution I declare that no material contained in the thesis has been used in any other submission for an academic award and is solely my own work Signature of Candidate: Philip R.Stone Type of Award: PhD School: School of Sport, Tourism & The Outdoors Abstract Despite increasing academic and media attention paid to dark tourism – the act of travel to sites of death, disaster and the seemingly macabre – understanding of the concept remains limited, particularly from a consumption perspective. That is, the literature focuses primarily on the supply of dark tourism. Less attention, however, has been paid to the consumption of ‗dark‘ touristic experiences and the mediation of such experiences in relation to modern-day mortality. This thesis seeks to address this gap in the literature. Drawing upon thanatological discourse – that is, the analysis of society‘s perceptions of and reactions to death and dying – the research objective is to explore the potential of dark tourism as a means of contemplating mortality in (Western) societies. In so doing, the thesis appraises dark tourism consumption within society, especially within a context of contemporary perspectives of death and, consequently, offers an integrated theoretical and empirical critical analysis and interpretation of death-related travel. -

The 2021 Youth Rugby Tour Brochure

Gateshead RFC running out with Rugby Colorno ahead of a final tour fixture in Parma with The Rugby Tour Specialists. Sky High Sports is a Rugby Specialist Tour Operator which excels at combining Rugby and Travel to provide once in a lifetime experiences for good Rugby people across the world. Our commitment to offering innovative, exciting and bespoke tours along with our client focused, personal and dedicated approach has allowed us to build a global portfolio of clients and earn a reputation of excellence in our field. Our team is made up of passionate rugby playing people & travel experts who take pride in introducing you to the vast rugby cultures of Europe through the great tradition of touring. Every one of our Rugby Tour itineraries has been developed from our own individual and professional experiences, alongside some superb rugby people which gives every trip a personal approach that we take a lot of pleasure in sharing with you. Sky High Sports are the Rugby Tour Specialists. Hello & Welcome to Sky High Sports. Now that the world seems to be returning slowly towards a brighter future, we are certainly casting more than a keen eye to when we can all hop on Tour Buses and get our touring careers back on track sooner rather than later. We were not alone in facing the challenges that recent months presented, it has however given us a bonus opportunity to adapt and further improve our business from top to bottom. We have to evolve into the future & we have taken this one-off chance to come back better than ever. -

Grim Faces Wanted!

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Grim Faces Wanted! York Attraction search for a new model with a twist More high resolution images can be found here The York Dungeon are looking for a model for their brand-new character. There’s just one condition; you must be able to pull a hideous face. Previously, the York attraction have used their own actors to promote new additions to the site. However, this time they are taking a different route. New character Ugly Horace/Hilda will be a permanent fixture at the York Dungeon; their face will take pride of place on a board outside the Dungeon, horrifying every guest that enters. Entry to the competition is simple – just send in an image of you pulling the strangest and most unusual face possible. The winning entrant will be invited to the attraction for a photoshoot in full dungeon costume. “Our actors can pull some incredibly grim and inhuman faces, but we want to find someone even more wretched!” said Marketing Executive Ben Rosenfield. “Whoever is the unfortunate winner will be immortalised in the attraction and across all of our social media channels. We’ll also throw in a VIP ticket to the attraction.” Since opening in 1986, a plethora of historical figures and maniacal characters have dwelled within the depth of the York Dungeon. These rogues and rascals have included: the nefarious highwayman Dick Turpin; the unfortunate Margaret Clitherow; the vicious queen of the Brigante tribe Cartimandua and the terrifying Isabella Billington, who was executed for witchcraft in 1649. There are a few ways to submit your shocking selfies; message York Dungeon on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram or use #GrimFaceYork email [email protected]. -

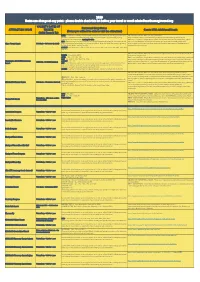

2020 Dates Can Change at Any Point - Please Double Check This List Before Your Travel Or Email [email protected]

2020 Dates can change at any point - please double check this list before your travel or email [email protected] VALIDITY DATES OF Restricted Entry Dates ATTRACTION NAME TICKETS Guests With Additional Needs (Dates you will not be able to visit the attraction) (Valid From & To) APRIL – Easter Bank Holiday – not restricted but we strongly advise not attending at this time as • GUESTS WITH ADDITIONAL NEEDS – please visit the Park is expected to be extremely busy which can have an effect on travel time, parking, https://www.altontowers.com/media/buhjammz/online-resort-access-guide-2019.pdf queuing for ride access passes, queuing for rides • RIDE ACCESS PASSES - Magic Wand’s tickets do not cover ride access or priority entry, please MAY – Bank Holidays – not restricted but we strongly advise not attending on these dates as the visit. For full information including a form to help you save time on the day please visit - Alton Towers Resort 21st March – 1st October (included) park is expected to be extremely busy which can have an effect on travel time, parking, queuing https://support.altontowers.com/hc/en-us/articles/360000458092-What-is-the-Ride-Access- for ride access passes, queuing for rides System-and-how-do-I-apply- AUGUST – not valid on 1st, 2nd, 7th, 8th, 9th, 14th, 15th, 16th, 21st, 22nd, 23rd, 28th, 29th, 30th and 31st. • GUESTS WITH ADDITIONAL NEEDS –please visit https://www.chessington.com/plan/disabled- MARCH – Closed 24th & 25th guide-for-chessington.aspx APRIL – 10th, 11th, 12th, 13th • RIDE ACCESS PASSES - Magic Wand’s -

Attractions Management News 18Th December 2019 Issue

Find great staff™ Jobs start on page 24 MANAGEMENT NEWS 18 DECEMBER 2019 IssUE 146 www.attractionsmanagement.com David Bowie exhibition for space centre The UK's National Space Centre will host an immersive live experience celebrating the life of music icon David Bowie. The ultimate LIVE immersive show will chart Bowie's life through the years from 1969 to 1972, a significant period of time which covered both Bowie’s experimental I MA phase (Space Oddity to Ziggy Stardust) G E : N and the Apollo lunar landing window. ational Housed in the centre's Sir Patrick S pa Moore Planetarium during January CE C 2020, the experience will include ENT R live music performances by a tribute E band, as well as an exhibition ■■The experience includes live music of media inspired by Bowie. "As part of our celebration we Paul McNicoll, Associate Professor for have partnered with De Montfort Student Experience at DMU, said of the University, Loughborough University exhibition in a statement: "Inspired by the and Leicester College to create a never Apollo missions and the work of David before seen exhibition of fashion, Bowie, they will be showcasing innovative The show will be inspired textiles, art and photography inspired designs across fashion, textiles, by the Apollo missions and by David Bowie," a spokesperson for intimates, footwear and accessories." the work of David Bowie the National Space Centre said. MORE:READ http: MO//lei.sr/e4A6H_ARE ONLINE Paul McNicoll LATEST JOBS MUSEUMS THEME PARKS European Museum of the Work begins on Zootopia Year nominees revealed land in Shanghai 61 institutions to compete p4 Disney looks to benefit p6 p24 for prestigious award from popularity of movie Attractions people Holovis' Heidi Pinchal reveals details of Discovery Destinations partnership iscovery Destinations, a even further by utilising our specialist in real-world proprietary software suites Dentertainment, has such as HoloTrac," said announced a new strategic Holovis' Heidi Pinchal. -

E-Inbusiness Streamlines Online Ticket Sales at Submitted By: PR Artistry Limited Friday, 20 July 2001

e-InBusiness streamlines online ticket sales at www.thedungeons.com Submitted by: PR Artistry Limited Friday, 20 July 2001 No more queuing for visitors to the spine-chilling leading tourist attractions e-InBusiness, specialist in transactional e-commerce systems, has enabled www.thedungeons.com to increase ticket sales with a new efficient on-line web site. The project to build a new Ticket & Gift Shop using proven technology took just three months and replaces a previous system that was difficult for customers to use. The new on-line store enables visitors to the site to buy tickets for The London Dungeon, The Edinburgh Dungeon, The York Dungeon and The Hamburg Dungeon and to buy a selection of unusual and macabre gifts. Customers choose which language they prefer, English or German, and which currency, Sterling, Deutschmarks, Euros or US Dollars. The system automatically calculates the relevant taxes applying VAT where appropriate, transparently to the customer. The person making the booking receives a confirmation email, which when printed acts as an e-ticket. People booking online gain the added benefit of fast track entry, which saves queuing. On-line reports of tickets sold are available and each attraction receives a daily email with details of the online tickets booked for that day. Orders for gifts are automatically transmitted on-line to a fulfilment centre Chrissi Drunk, project manager at Merlin Entertainments, the owner of the four Dungeons commented, “We set e-InBusiness very tight deadlines, and they were very committed to meeting those deadlines. “Ticket sales have increased since we introduced the new site. -

Region Ticket Validity & Exclusion Dates 2017/2018

Attraction Region Ticket Validity & Exclusion dates 2017/2018 • Tickets Valid 19th March 2018 - 19th Oct 2018 (Dates Cannot be extended) • April – 1st -15th • May – 5th -7th and 26th – 31st • June 1st – 3rd Alton Towers Resort UK & Eire • August 1st – 31st • October 13th-14th and 20th -31st • November 1st-4th • Tickets do not include the Waterpark 17th March until the 18th (Inclusive) October 2018 (Dates Cannot be extended) • MARCH - 30th, 31st March (inclusive) • APRIL – 1st - 2nd (inclusive) • MAY - 5th, 6th,7th,26th,27th, 28th Chessington World Of Adventures Resort UK & Eire • AUGUST – 17th – 31st(inclusive) • SEPTEMBER - 1st – 3rd (inclusive) • OCTOBER - 13th - 14th (inclusive) • No Restricted Dates (although please avoid School/Summer/public/public Cornish SEA LIFE Sanctuary Gweek Cornwall UK & Eire holidays as the attraction will be busier than normal) Hunstanton SEA LIFE Sanctuary UK & Eire • DECEMBER 25th - 26th (inclusive) LEGOLAND Discovery Centre Birmingham UK & Eire 27/10/18-04/11/18 • No Restricted Dates (although please avoid School/Summer/public/public LEGOLAND Discovery Centre Manchester UK & Eire holidays as the attraction will be busier than normal) Entry is Valid From 13th March until the 28th October 2018 (This date unfortunately cannot be extended). • MARCH - 30th, 31st March • APRIL – 1st - 2nd (inclusive) • MAY 5th - 7th (inclusive) LEGOLAND Windsor Resort UK & Eire • MAY - 26th - 28th (inclusive) • AUGUST - 20th - 31st (inclusive) • SEPTEMBER 1st - 2nd (inclusive) • OCTOBER 13th - 14th (inclusive) Madame Tussauds -

Important the Information Contained in This Document

DISCLAIMER - IMPORTANT THE INFORMATION CONTAINED IN THIS DOCUMENT (“DOCUMENT”) HAS BEEN MADE AVAILABLE IN ORDER TO COMPLY WITH ENGLISH LAW AND THE CITY CODE ON TAKEOVERS AND MERGERS. THIS DOCUMENT DOES NOT CONSTITUTE AN OFFER TO SELL OR OTHERWISE DISPOSE OF, OR AN INVITATION OR SOLICITATION OF ANY OFFER TO PURCHASE OR SUBSCRIBE FOR, ANY SECURITIES IN ANY JURISDICTION. THIS DOCUMENT DOES NOT CONSTITUTE A PROSPECTUS. THE NOTES DESCRIBED IN THIS DOCUMENT HAVE NOT BEEN REGISTERED WITH, RECOMMENDED BY OR APPROVED BY THE SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION (THE “SEC”), OR ANY OTHER SECURITIES COMMISSION OR REGULATORY AUTHORITY, NOR HAS THE SEC NOR ANY SUCH OTHER SECURITIES COMMISSION OR AUTHORITY PASSED UPON THE ACCURACY OR ADEQUACY OF THIS DOCUMENT. ANY REPRESENTATION TO THE CONTRARY IS A CRIMINAL OFFENCE. NOTES MAY NOT BE OFFERED OR SOLD WITHIN THE UNITED STATES EXCEPT PURSUANT TO AN EXEMPTION FROM, OR IN A TRANSACTION NOT SUBJECT TO, THE REGISTRATION REQUIREMENTS OF THE SECURITIES ACT. THE RELEASE, PUBLICATION OR DISTRIBUTION OF THIS DOCUMENT IN, INTO OR FROM JURISDICTIONS OTHER THAN THE UNITED KINGDOM OR THE UNITED STATES MAY BE RESTRICTED BY THE LAWS OF THOSE JURISDICTIONS AND THEREFORE PERSONS INTO WHOSE POSSESSION THESE DOCUMENTS COME SHOULD INFORM THEMSELVES ABOUT, AND OBSERVE, SUCH RESTRICTIONS. ANY FAILURE TO COMPLY WITH THE RESTRICTIONS MAY CONSTITUTE A VIOLATION OF THE SECURITIES LAWS OF ANY SUCH JURISDICTION. TO THE FULLEST EXTENT PERMITTED BY LAW, MERLIN ENTERTAINMENTS PLC AND MOTION ACQUISITION LIMITED DISCLAIM ANY RESPONSIBILITY OR LIABILITY FOR THE VIOLATION OF SUCH RESTRICTIONS BY SUCH PERSONS. THE INFORMATION CONTAINED IN THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN FURNISHED BY US AND FROM OTHER SOURCES WE BELIEVE TO BE RELIABLE.