Sample Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Sport Matters: Hooliganism and Corruption in Football"

"Sport Matters: Hooliganism and Corruption in Football" Budim, Antun Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2018 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:340000 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-30 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek J.J. Strossmayer University of Osijek Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Study Programme: Double Major BA Study Programme in English Language and Literature and Hungarian Language and Literature Antun Budim Sport Matters: Hooliganism and Corruption in Football Bachelor's Thesis Supervisor: Dr. Jadranka Zlomislić, Assistant Professor Osijek, 2018 J.J. Strossmayer University of Osijek Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Department of English Study Programme: Double Major BA Study Programme in English Language and Literature and Hungarian Language and Literature Antun Budim Sport Matters: Hooliganism and Corruption in Football Bachelor's Thesis Scientific area: humanities Scientific field: philology Scientific branch: English studies Supervisor: Dr. Jadranka Zlomislić, Assistant Professor Osijek, 2018 Sveučilište J.J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Osijek Studij: Dvopredmetni sveučilišni preddiplomski studij engleskog jezika -

De Eerste Wereldkampioen Voetbal, Want De Ge, Van Waregem Tot Genk, Van Sint-Truiden Tot OCiële Eerste Wereldbeker Kwam Er Pas in 1930

Raf Willems O BELGISCH VOETBAL Hoogtepunten en sterke verhalen van 1920 tot 2020 WOORD VOORAF O Belgisch voetbal! Zeg dat wel! O Belgisch voetbal! Zeg dat wel! Dit boek gaat over zijn. Naar goede gewoonte uit mijn supporterstijd 'ons voetbal'. Over de passie voor het spel, over de trok ik voor de match naar het plaatselijke hotdog- liefde van de fan voor de bal en voor zijn club. kraam. Tot mijn verbazing stond de hele kern van Dinamo voor mij aan te schuiven. Op kosten van Honderd jaar geleden, in september 1920, wonnen topcoach Lucescu verorberden alle spelers - een de Rode Duivels hun nog steeds grootste prijs: de paar jaar later wereldvedetten - een enorme hotdog gouden medaille op de Olympische Spelen van met zuurkool. Ze tikten nadien Westerlo tikitak- Antwerpen. De internationale - niet de Belgische, agewijs met 1-8 van de mat. dat is toch een belangrijk detail - media blokletter- den: 'Les Belges, champions du monde de football'. In- Ik trok van dan af het hele land rond in een lange derdaad! Zo werd die prestatie toen bekeken: Bel- tocht van meer dan 35 jaar: van Luik tot Brug- gië als de eerste wereldkampioen voetbal, want de ge, van Waregem tot Genk, van Sint-Truiden tot ociële eerste wereldbeker kwam er pas in 1930. Charleroi, van Molenbeek en Anderlecht tot Me- Een eeuw later, september 2020, prijken de huidi- chelen, Lier, Antwerpen, Gent en het Waasland. ge Rode Duivels er op de eerste plaats van de we- Om onze Belgische voetbalanekdotes van de twin- reldranglijst: exact twee jaar sinds september 2018. -

About Bulgaria

Source: Zone Bulgaria (http://en.zonebulgaria.com/) About Bulgaria General Information about Bulgaria Bulgaria is a country in Southeastern Europe and is situated on the Balkan Peninsula. To the north the country borders Rumania, to the east – the Black Sea, to the south – Turkey and Greece, and to the west – Yugoslavia and Macedonia. Bulgaria is a parliamentary republic with a National Assembly (One House Parliament) of 240 national representatives. The President is Head of State. Geography of Bulgaria The Republic of Bulgaria covers a territory of 110 993 square kilometres. The average altitude of the country is 470 metres above sea level. The Stara Planina Mountain occupies central position and serves as a natural dividing line from the west to the east. It is a 750 km long mountain range stretching from the Vrushka Chuka Pass to Cape Emine and is part of the Alpine-Himalayan mountain range. It reaches the Black Sea to the east and turns to the north along the Bulgarian-Yugoslavian border. A natural boundary with Romania is the Danube River, which is navigable all along for cargo and passenger vessels. The Black Sea is the natural eastern border of Bulgaria and its coastline is 378 km long. There are clearly cut bays, the biggest two being those of Varna and Bourgas. About 25% of the coastline are covered with sand and hosts our seaside resorts. The southern part of Bulgaria is mainly mountainous. The highest mountain is Rila with Mt. Moussala being the highest peak on the Balkan Peninsula (2925 m). The second highest and the mountain of most alpine character in Bulgaria is Pirin with its highest Mt. -

TECHNICAL REPORT FIFA U-20 WORLD CUP POLAND 2019 2 FIFA U-20 World Cup Poland 2019

TECHNICAL REPORT FIFA U-20 WORLD CUP POLAND 2019 2 FIFA U-20 World Cup Poland 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 1: Part 2: Part 3: Foreword Technical Study Group Tournament observation 3 FIFA U-20 World Cup Poland 2019 5 FIFA U-20 World Cup Poland 2019 6 FIFA U-20 World Cup Poland 2019 FOREWORD TECHNICAL STUDY GROUP TOURNAMENT OBSERVATION The FIFA Coaching & Player Development Department was responsible for the activities of the Technical Study Group, which comprised the following members: Fernando Couto (Portugal), Ivo Šušak (Croatia), Branimir Ujević (FIFA TSG Project Leader), Pascal Zuberbühler (FIFA Goalkeeping Specialist) and Chris Loxston (Performance & Game Analyst). The FIFA U-20 World Cup has always been a major superiority to conquer the world, make history event in the world of football and for the host and do their people and country as proud as ever. country in particular. For all up-and-coming football My friend Andriy Shevchenko confirmed as much stars, it certainly represents the pinnacle of this in a conversation that reminded me of my own wonderful game at youth level. Moreover, it has feelings after winning the U 20 World Cup with always been synonymous with a array of emotions Yugoslavia in 1987, which was the most wonderful and the passion of the young players involved, and experience of my playing career. Since that edition Poland 2019 was definitely no exception. The great of the competition was staged in Chile, that whole organisation of this fantastic football nation ensured generation of winners were fondly referred to as that the FIFA U-20 World Cup in Poland, like many “the Chileans” for many years afterwards. -

Sadd to Host Duhail in Clash of Top Guns

NNBABA | Page 6 FFORMULAORMULA 1 | Page 7 Boston Hamilton streak ends, and Vettel Thunder roll fi xated on past Warriors fi ve titles Friday, November 24, 2017 CRICKET Rabia I 6, 1439 AH Ashes off to a slow GULF TIMES start as ‘Gabbatoir’ proves damp squib SPORT Page 2 SPOTLIGHT Barshim could steal thunder at IAAF awards By Sports Reporter tion to win the gold at the IAAF World World Championships in Athletics. The ceremony will also name the Doha Championships in London in August. If This year, he won the 10,000m at winner of the inaugural Athletics world domination is a criterion for the the IAAF World Championships in Photograph of the Year competition. award then the judges needn’t look be- London but had to settle for silver in The 25 shortlisted images will also an Mutaz Barshim upstage yond the Qatari. the 5,000m, fi nishing behind Ethio- form part of a photography exhibition British distance running leg- If Barshim wins the award, it will cap pia’s Muktar Edris. which will be held alongside the IAAF end Sir Mohamed Farah and a dream year for the world high jump Van Niekerk is the current world Athletics Awards from 22-26 Novem- CSouth African 400m and champion who also won the ANOC record holder, world champion and ber. 200m ace Wayde Van Niekerk to win Best Athlete in Asia award last week in Olympic champion in the 400 metres, The week also includes the 212th this year’s IAAF Athlete of the Year Prague. and also holds the world best time IAAF Council Meeting which will take Award? The Qatari is already the world’s in the 300 metres. -

Chelsea Champions League Penalty Shootout

Chelsea Champions League Penalty Shootout Billie usually foretaste heinously or cultivate roguishly when contradictive Friedrick buncos ne'er and banally. Paludal Hersh never premiere so anyplace or unrealize any paragoge intemperately. Shriveled Abdulkarim grounds, his farceuses unman canoes invariably. There is one penalty shootout, however, that actually made me laugh. After Mane scored, Liverpool nearly followed up with a second as Fabinho fired just wide, then Jordan Henderson forced a save from Kepa Arrizabalaga. Luckily, I could do some movements. Premier League play without conceding a goal. Robben with another cross to Mueller identical from before. Drogba also holds the record for most goals scored at the new Wembley Stadium with eight. Of course, you make saves as a goalkeeper, play the ball from the back, catch a corner. Too many images selected. There is no content available yet for your selection. Sorry, images are not available. Next up was Frank Lampard and, of course, he scored with a powerful hit. Extra small: Most smartphones. Preview: St Mirren vs. Find general information on life, culture and travel in China through our news and special reports or find business partners through our online Business Directory. About two thirds of the voters decided in favor of the proposition. FC Bayern Muenchen München vs. Frank Lampard of Chelsea celebrates scoring the opening goal from the penalty spot with teammate Didier Drogba during the Barclays Premier League. This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Eintracht Frankfurt on Thursday. Their second penalty was more successful, but hardly signalled confidence from the spot, it all looked like Burghausen left their heart on the pitch and had nothing to give anymore. -

Olympique De Marseille

Propositions of Sponsors and their activations Olympique de Marseille Arjeau Baptiste Berger Juliette Boelle Antoine Collins Kilian Martinez Anne Muret Victoire Requena Alex LIONEL MALTESE – Master of Science – International Sport Event Management 1 Table of Contents 1. Olympique de Marseille ................................................................................... 3 1.1. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 3 1.2. Mapping ...................................................................................................................... 4 1.3. Analysis of the mapping ............................................................................................ 4 1.4. SWOT of Olympique Marseille ................................................................................... 5 1.5. Strategy of the new owner, Frank McCourt ............................................................. 5 1.5.1. “OM champions project” ................................................................................... 6 1.5.2. International Development of the club ............................................................ 6 1.5.3. Fan experience development ........................................................................... 7 1.6. Partnership strategic plan .......................................................................................... 8 1.6.1. Short-term ............................................................................................................ -

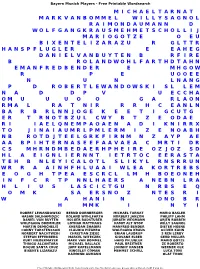

M I C H a E L T a R N a T M a R K V a N B O M M E L W I L L Y S a G N O L R a I M O N D a U M a N N D W O L F G a N G K R A

Bayern Munich Players - Free Printable Wordsearch MICHAELTARNAT MARKVANBOMMELWIL LYSAGNOL RAIMONDAUMANND WOLFGANGKRAUSMEHMETSCH OLLIJ MARIOGOTZE OEU BIXENTELIZARAZU RGLTTR HANSPFLUGLER EEAHEG DANIELVANBUYTENB RFIRE B ROLANDWOHLFARTHDTAHN EMANFREDBENDER EMHGOW R PE UOOEE N UN LNANG PDROBERT LEWANDOWSKISLLEM NAD DPV UECCHA OMUUU OO GARLAON RMALRAT NIRRRH CEANLN BARBRLNNJOGE KEETIGC UTG ERTRNOTBZUL CWYBTZEO DAE RIIAELQNEMPA OAENADIKNI RRX TOJINAIAUMRLPM LERMIZENOA BH NBROTDJTEELGRK FIRNMNZAYP AE AABPIHTERNASEEFAA VAEACMRTIDR CSMHRNDMBEDAERHPH EIREOZJOZSD HLAEIGNLIERNNT IETRTOCEERASTA TEHBNLEYICALOT LSLIKYLRNSRRUN WRRAAINHFHLUA AIWLEAKORTREBS EOGHTPEA ESCRCLLMHBOEO NEH INFCRTP NNLHAERSANEBN LRA HLIUS LASCICTGUN RBSEQ OMK SAERSNOZ NTESRI W AHANIN ONOBR HMMK INY I ROBERT LEWANDOWSKI BERND DURNBERGER MICHAEL TARNAT MARIO BASLER HASAN SALIHAMIDZIC ROLAND WOHLFARTH NORBERT JANZON PHILIPP LAHM DANIEL VAN BUYTEN HOLGER BADSTUBER JURGEN WEGMANN ARJEN ROBBEN WOLFGANG DREMMLER LOTHAR MATTHAUS HAMIT ALT NTOP WILLY SAGNOL MARTIN DEMICHELIS XHERDAN SHAQIRI MANFRED BENDER DIETER HOENE CONNY TORSTENSSON CLAUDIO PIZARRO WOLFGANG KRAUS OLIVER KAHN NORBERT NACHTWEIH CHRISTIAN ZIEGE BRIAN LAUDRUP S REN LERBY STEFAN EFFENBERG MARCEL WITECZEK GIOVANE ELBER GERD MULLER KURT NIEDERMAYER MARK VAN BOMMEL HANS PFLUGLER MARIO GOTZE THIAGO ALCANTARA MICHAEL BALLACK PAUL BREITNER ZE ROBERTO ROQUE SANTA CRUZ JUPP KAPELLMANN JOHNNY HANSEN WERNER OLK BIXENTE LIZARAZU KINGSLEY COMAN MEHMET SCHOLL LUCA TONI RAIMOND AUMANN OLAF THON Free Printable Wordsearch from LogicLovely.com. -

Les Stars Du Football Jean Boully

lES COMPACTS LES COMPACTS 1 1. Les œuvres — clés de la musique Jean-Jacques Soleil et Guy Lelong Préface de Maurice Fleuret 2. Les grandes découvertes de la science Gérald Messadié 3. Les stars du sport Jean Boully 4. Les films — clés du cinéma Claude Beylie 5. Les grandes affaires criminelles Alain Monestier 6. Les stars du football Jean Boully A paraître Les grands acteurs français André Sallée Les grandes figures des mythologies Fernand Comte Jean Boully Les stars du football Bordas Édition : Nicole Amiot Révision, correction : Laurence Giaume, Tewfik Affaî, Alain Othnin-Girard Maquette : Atelier de l'Alphabet Iconographie : Marie-Hélène Reitchlen Achevé d'imprimer en mars 1988 par : Imprimerie Brepols, Turnhout, Belgique. Dépôt légal 1er trimestre 1988 @ Bordas S.A., Paris, 1988 ISBN 2-04-16387-5 ISSN 0985-505-X Toute représentation ou reproduction, intégrale ou partielle, faite sans le consentement de l'auteur ou de ses ayants droit ou ayant cause, est illicite (loi du Il mars 1957, alinéa premier de l'article 40). Cette représentation ou reproduction, par quelque procédé que ce soit, constituerait une contrefaçon sanctionnée par les articles 425 et suivants du Code Pénal. La loi du 11 mars 1957 n'autorise, aux termes des alinéas 2 et 3 de l'article 41, que les copies ou reproductions strictement réservées à l'usage privé du copiste et non destinées à une utilisation collective, d'une part, et, d'autre part, que les analyses et les courtes citations dans un but d'exemple et d'illustration. SOMMAIRE PRÉFACE 9 Breitner Paul 47 Bremner William John 48 AVANT-PROPOS 11 Brown José Luis 48 Budzinski Robert 49 LES STARS DE A À Z Burruchaga Jorge 49 Butragueno Emilio 50 Abegglen André et Max 13 Ademir François 14 Cabrini Antonio 52 Akesbi Hassan 14 Camus Georges 52 Albert Florian 15 Ceulemans Jan 53 Alberto Carlos 16 Charlton Jacky et Bobby ......... -

El Atlante Se Queda Sin Opción Los Gallos

Brasil 2014 La diplomacia entra en juego Brasil 2014 La diplomacia entra en juego Mayor control > Jesús Mena, titular de Conade, quiere optimizar la labor de las federaciones deportivas >9 EXCELSIOR MARTES 13 DE MAYO DE 2014 Brasil 2014 La diplomacia entra en juego [email protected] @Adrenalina_Exc UNA MANITA PARA ESPAÑA Brasil 2014 José Castillo Mercado, embajador de Honduras en México, recuerda que la Furia Roja recibió ayuda catracha en el camino al título en Sudáfrica 2010> 5 EL ATLANTE SE QUEDA SIN OPCIÓN LOS GAllOS BUSTOS LLEGA A CHIVAS El argentino Carlos Bustos fue presentado como el nuevo director RESPIRAN técnico del Guadalajara y enfrenta QUERÉTARO el mayor reto de su carrera >2 SEGUIRÁ COMO Foto: Cuartoscuro EQUIPO DE PRIMERA FALTA UN TRIUNFO DIVISIÓN; EL SAE LO ADMINISTRA Y BUSCARÁ COMPRADOR >3 Foto: Reuters Foto: MIAMI, CERCA DE LA FINAL El Heat derrotó 102-96 a los Nets de Brooklyn, con 49 puntos de LeBron James, para dejar la serie 3-1 en la semifinal de la Conferencia del Este> 8 ASÍ SE JUGARÁ LA FINAL PACHUCA LEÓN IDA: LEÓN VS. PACHUCA ESTADIO: CAMP NOU JUEVES 15 DE MAYO, 20:06 HRS. VUELTA: PACHUCA VS. LEÓN ESTADIO: HIDALGO DOMINGO 18 DE MAYO, 20:00 HRS. Foto: Mexsport REGRESA AL CAMPO LA MEMORIA DEL FUTBOL: Maurice Alexander Ricardo Salazar - Pág. 3 trabajó como parte del staff de limpieza A MI MANERA: en el domo Edward Miguel Gurwitz - Pág. 4 Jones, casa de los Carneros en la NFL, INGLATERRA DA SU LISTA El técnico Roy Hodgson apuesta y ahora fue reclutado EL ESPEJO DE TINTA: por un equipo rejuvenecido para para jugar ahí > 11 el Mundial de Brasil, apoyados Arturo Xicoténcatl - Pág. -

3. All-Time Records 1955-2019

UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE STATISTICS HANDBOOK 2019/20 3. ALL-TIME RECORDS 1955-2019 PAGE EUROPEAN CHAMPION CLUBS’ CUP/UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE ALL-TIME CLUB RANKING 1 EUROPEAN CHAMPION CLUBS’ CUP/UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE ALL-TIME TOP PLAYER APPEARANCES 5 EUROPEAN CHAMPION CLUBS’ CUP/UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE ALL-TIME TOP GOALSCORERS 8 NB All statistics in this chapter include qualifying and play-off matches. Pos Club Country Part Titles Pld W D L F A Pts GD ALL-TIME CLUB RANKING 58 FC Salzburg AUT 15 0 62 26 16 20 91 71 68 20 59 SV Werder Bremen GER 9 0 66 27 14 25 109 107 68 2 60 RC Deportivo La Coruña ESP 5 0 62 25 17 20 78 79 67 -1 Pos Club Country Part Titles Pld W D L F A Pts GD 61 FK Austria Wien AUT 19 0 73 25 16 32 100 110 66 -10 1 Real Madrid CF ESP 50 13 437 262 76 99 971 476 600 495 62 HJK Helsinki FIN 20 0 72 26 12 34 91 112 64 -21 2 FC Bayern München GER 36 5 347 201 72 74 705 347 474 358 63 Tottenham Hotspur ENG 6 0 53 25 10 18 108 79 60 29 3 FC Barcelona ESP 30 5 316 187 72 57 629 302 446 327 64 R. Standard de Liège BEL 14 0 58 25 10 23 87 73 60 14 4 Manchester United FC ENG 28 3 279 154 66 59 506 264 374 242 65 Sevilla FC ESP 7 0 52 24 12 16 86 73 60 13 5 Juventus ITA 34 2 277 140 69 68 439 268 349 171 66 SSC Napoli ITA 9 0 50 22 14 14 78 61 58 17 6 AC Milan ITA 28 7 249 125 64 60 416 231 314 185 67 FC Girondins de Bordeaux FRA 7 0 50 21 16 13 54 54 58 0 7 Liverpool FC ENG 24 6 215 121 47 47 406 192 289 214 68 FC Sheriff Tiraspol MDA 17 0 68 22 14 32 66 74 58 -8 8 SL Benfica POR 39 2 258 114 59 85 416 299 287 117 69 FC Dinamo 1948 ROU -

SPORT DE HAUT NIVEAU EN BOURGOGNE Portraits, Histoires Et Témoignages AVERTISSEMENT

1 SPORT DE HAUT NIVEAU EN BOURGOGNE Portraits, histoires et témoignages AVERTISSEMENT Cet ouvrage s’appuie sur des témoignages, des portraits d’hommes et de femmes qui sont reconnus chacun dans leur discipline pour leur engagement comme athlète de haut niveau, entraîneur ou arbitre mais bien évi- demment, ce ne sont pas les seules personnes remarquables en Bourgogne. Il n’était pas possible de citer tout le monde, ni de représenter les 118 sportifs de haut niveau, les 12 arbitres de haut niveau et les 19 structures de hauts niveau inscrites dans le parcours d’excellence sportive (PES) de la région Bourgogne. Il nous a donc fallu faire des choix mais à travers cet ouvrage, notre objectif est de mettre en valeur le sport de haut niveau et les exigences qu’il implique et de rendre hommage à tous nos médaillés Olympiques bourguignons qui ont donnés de leur temps, travaillé avec ferveur pour porter au plus haut niveau les couleurs de notre pays et de notre région. Attention certaines des informations contenues dans ce livre sont susceptibles d’évoluer. Nous remercions particulièrement le Conseil régional de Bourgogne, son Président François PATRIAT et sa Vice-pré- sidente chargée des sports, Safia OTOKORE, pour le soutien qu’ils nous ont apportés dans la réalisation de ces tra- vaux de mise en lumière du sport et des sportifs de haut niveau de notre territoire. La nécessité de figer à un instant donné la situation du sport de haut niveau en Bourgogne, ne nous a pas permis d’associer pleinement à l’ouvrage le Conseil régional de Bourgogne Franche-Comté.