Jim Sheridan Framing the Nation, R.Barton.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CELEBRATING FORTY YEARS of FILMS WORTH TALKING ABOUT 39 Years, 2 Months, and Counting…

5 JAN 18 1 FEB 18 1 | 5 JAN 18 - 1 FEB 18 88 LOTHIAN ROAD | FILMHOUSECinema.COM CELEBRATING FORTY YEARS OF FILMS WORTH TALKING ABOUT 39 Years, 2 Months, and counting… As you’ll spot deep within this programme (and hinted at on the front cover) January 2018 sees the start of a series of films that lead up to celebrations in October marking the 40th birthday of Filmhouse as a public cinema on Lothian Road. We’ve chosen to screen a film from every year we’ve been bringing the very best cinema to the good people of Edinburgh, and while it is tremendous fun looking back through the history of what has shown here, it was quite an undertaking going through all the old programmes and choosing what to show, and a bit of a personal journey for me as one who started coming here as a customer in the mid-80s (I know, I must have started very young...). At that time, I’d no idea that Filmhouse had only been in existence for less than 10 years – it seemed like such an established, essential institution and impossible to imagine it not existing in a city such as Edinburgh. My only hope is that the cinema is as important today as I felt it was then, and that the giants on whose shoulders we currently stand feel we’re worthy of their legacy. I hope you can join us for at least some of the screenings on this trip down memory lane... And now, back to the now. -

The Role of Irish-Language Film in Irish National Cinema Heather

Finding a Voice: The Role of Irish-Language Film in Irish National Cinema Heather Macdougall A Thesis in the PhD Humanities Program Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada August 2012 © Heather Macdougall, 2012 ABSTRACT Finding a Voice: The Role of Irish-Language Film in Irish National Cinema Heather Macdougall, Ph.D. Concordia University, 2012 This dissertation investigates the history of film production in the minority language of Irish Gaelic. The objective is to determine what this history reveals about the changing roles of both the national language and national cinema in Ireland. The study of Irish- language film provides an illustrative and significant example of the participation of a minority perspective within a small national cinema. It is also illustrates the potential role of cinema in language maintenance and revitalization. Research is focused on policies and practices of filmmaking, with additional consideration given to film distribution, exhibition, and reception. Furthermore, films are analysed based on the strategies used by filmmakers to integrate the traditional Irish language with the modern medium of film, as well as their motivations for doing so. Research methods included archival work, textual analysis, personal interviews, and review of scholarly, popular, and trade publications. Case studies are offered on three movements in Irish-language film. First, the Irish- language organization Gael Linn produced documentaries in the 1950s and 1960s that promoted a strongly nationalist version of Irish history while also exacerbating the view of Irish as a “private discourse” of nationalism. Second, independent filmmaker Bob Quinn operated in the Irish-speaking area of Connemara in the 1970s; his fiction films from that era situated the regional affiliations of the language within the national context. -

You Can Find Details of All the Films Currently Selling/Coming to Market in the Screen

1 Introduction We are proud to present the Fís Éireann/Screen Irish screen production activity has more than Ireland-supported 2020 slate of productions. From doubled in the last decade. A great deal has also been comedy to drama to powerful documentaries, we achieved in terms of fostering more diversity within are delighted to support a wide, diverse and highly the industry, but there remains a lot more to do. anticipated slate of stories which we hope will Investment in creative talent remains our priority and captivate audiences in the year ahead. Following focus in everything we do across film, television and an extraordinary period for Irish talent which has animation. We are working closely with government seen Irish stories reach global audiences, gain and other industry partners to further develop our international critical acclaim and awards success, studio infrastructure. We are identifying new partners we will continue to build on these achievements in that will help to build audiences for Irish screen the coming decade. content, in more countries and on more screens. With the broadened remit that Fís Éireann/Screen Through Screen Skills Ireland, our skills development Ireland now represents both on the big and small division, we are playing a strategic leadership role in screen, our slate showcases the breadth and the development of a diverse range of skills for the depth of quality work being brought to life by Irish screen industries in Ireland to meet the anticipated creative talent. From animation, TV drama and demand from the sector. documentaries to short and full-length feature films, there is a wide range of stories to appeal to The power of Irish stories on screen, both at home and all audiences. -

Sherlock Holmes

sunday monday tuesday wednesday thursday friday saturday KIDS MATINEE Sun 1:00! FEB 23 (7:00 & 9:00) FEB 24 & 25 (7:00 & 9:00) FEB 26 & 27 (3:00 & 7:00 & 9:15) KIDS MATINEE Sat 1:00! UP CLOUDY WITH A CHANCE OF MEATBALLS THE HURT LOCKER THE DAMNED PRECIOUS FEB 21 (3:00 & 7:00) Director: Kathryn Bigelow (USA, 2009, 131 mins; DVD, 14A) Based on the novel ‘Push’ by Sapphire FEB 22 (7:00 only) Cast: Jeremy Renner Anthony Mackie Brian Geraghty Ralph UNITED Director: Lee Daniels Fiennes Guy Pearce . (USA, 2009, 111 min; 14A) THE IMAGINARIUM OF “AN INSTANT CLASSIC!” –Wall Street Journal Director: Tom Hooper (UK, 2009, 98 min; PG) Cast: Michael Sheen, Cast: Gabourey Sidibe, Paula Patton, Mo’Nique, Mariah Timothy Spall, Colm Meaney, Jim Broadbent, Stephen Graham, Carey, Sherri Shepherd, and Lenny Kravitz “ENTERS THE PANTEHON and Peter McDonald DOCTOR PARNASSUS OF GREAT AMERICAN WAR BEST SUPPORTING ACTRESS MO’NIQUE FILMS!” –San Francisco “ONE OF THE BEST FILMS OF THE GENRE!” –Golden Globes, Screen Actors Guild Director: Terry Gilliam (UK/Canada/France, 2009, 123 min; PG) –San Francisco Chronicle Cast: Heath Ledger, Christopher Plummer, Tom Waits, Chronicle ####! The One of the most telling moments of this shockingly beautiful Lily Cole, Johnny Depp, Colin Farrell, and Jude Law Hurt Locker is about a bomb Can viewers who don’t know or care much about soccer be convinced film comes toward the end—the heroine glances at a mirror squad in present-day Iraq, to see Damned United? Those who give it a whirl will discover a and sees herself. -

12 Hours Opens Under Blue Skies and Yellow Flags

C M Y K INSPIRING Instead of loading up on candy, fill your kids’ baskets EASTER with gifts that inspire creativity and learning B1 Devils knock off county EWS UN s rivals back to back A9 NHighlands County’s Hometown Newspaper-S Since 1927 75¢ Cammie Lester to headline benefit Plan for spray field for Champion for Children A5 at AP airport raises a bit of a stink A3 www.newssun.com Sunday, March 16, 2014 Health A PERFECT DAY Dept. in LP to FOR A RACE be open To offer services every other Friday starting March 28 BY PHIL ATTINGER Staff Writer SEBRING — After meet- ing with school and coun- ty elected officials Thurs- day, Florida Department of Health staff said the Lake Placid office at 106 N, Main Ave. will be reopen- ing, but with a reduced schedule. Tom Moran, depart- ment spokesman, said in a Katara Simmons/News-Sun press release that the Flor- The Mobil 1 62nd Annual 12 Hours of Sebring gets off to a flawless start Saturday morning at Sebring International Raceway. ida Department of Health in Highlands County is continuing services at the Lake Placid office ev- 12 Hours opens under blue ery other Friday starting March 28. “The Department con- skies and yellow flags tinues to work closely with local partners to ensure BY BARRY FOSTER Final results online at Gurney Bend area of the health services are avail- News-Sun Correspondent www.newssun.com 3.74-mile course. Emergen- able to the people of High- cy workers had a tough time lands County. -

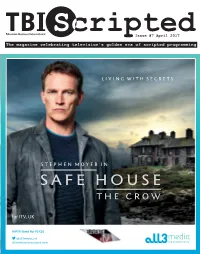

STEPHEN MOYER in for ITV, UK

Issue #7 April 2017 The magazine celebrating television’s golden era of scripted programming LIVING WITH SECRETS STEPHEN MOYER IN for ITV, UK MIPTV Stand No: P3.C10 @all3media_int all3mediainternational.com Scripted OFC Apr17.indd 2 13/03/2017 16:39 Banijay Rights presents… Provocative, intense and addictive, an epic retelling A riveting new drama series Filled with wit, lust and moral of the story of Versailles. Brand new second season. based on the acclaimed dilemmas, this five-part series Winner – TVFI Prix Export Fiction Award 2017. author Åsa Larsson’s tells the amazing true story of CANAL+ CREATION ORIGINALE best-selling crime novels. a notorious criminal barrister. Sinister events engulf a group of friends Ellen follows a difficult teenage girl trying A husband searches for the truth when A country pub singer has a chance meeting when they visit the abandoned Black to take control of her life in a world that his wife is the victim of a head-on with a wealthy city hotelier which triggers Lake ski resort, the scene of a horrific would rather ignore her. Winner – Best car collision. Was it an accident or a series of events that will change her life crime. Single Drama Broadcast Awards 2017. something far more sinister? forever. New second series in production. MIPTV Stand C20.A banijayrights.com Banijay_TBI_DRAMA_DPS_AW.inddScriptedpIFC-01 Banijay Apr17.indd 2 1 15/03/2017 12:57 15/03/2017 12:07 Banijay Rights presents… Provocative, intense and addictive, an epic retelling A riveting new drama series Filled with wit, lust and moral of the story of Versailles. -

KATHRINE GORDON Hair Stylist IATSE 798 and 706

KATHRINE GORDON Hair Stylist IATSE 798 and 706 FILM DOLLFACE Department Head Hair/ Hulu Personal Hair Stylist To Kat Dennings THE HUSTLE Personal Hair Stylist and Hair Designer To Anne Hathaway Camp Sugar Director: Chris Addison SERENITY Personal Hair Stylist and Hair Designer To Anne Hathaway Global Road Entertainment Director: Steven Knight ALPHA Department Head Studio 8 Director: Albert Hughes Cast: Kodi Smit-McPhee, Jóhannes Haukur Jóhannesson, Jens Hultén THE CIRCLE Department Head 1978 Films Director: James Ponsoldt Cast: Emma Watson, Tom Hanks LOVE THE COOPERS Hair Designer To Marisa Tomei CBS Films Director: Jessie Nelson CONCUSSION Department Head LStar Capital Director: Peter Landesman Cast: Gugu Mbatha-Raw, David Morse, Alec Baldwin, Luke Wilson, Paul Reiser, Arliss Howard BLACKHAT Department Head Forward Pass Director: Michael Mann Cast: Viola Davis, Wei Tang, Leehom Wang, John Ortiz, Ritchie Coster FOXCATCHER Department Head Annapurna Pictures Director: Bennett Miller Cast: Steve Carell, Channing Tatum, Mark Ruffalo, Siena Miller, Vanessa Redgrave Winner: Variety Artisan Award for Outstanding Work in Hair and Make-Up THE MILTON AGENCY Kathrine Gordon 6715 Hollywood Blvd #206, Los Angeles, CA 90028 Hair Stylist Telephone: 323.466.4441 Facsimile: 323.460.4442 IATSE 706 and 798 [email protected] www.miltonagency.com Page 1 of 6 AMERICAN HUSTLE Personal Hair Stylist to Christian Bale, Amy Adams/ Columbia Pictures Corporation Hair/Wig Designer for Jennifer Lawrence/ Hair Designer for Jeremy Renner Director: David O. Russell -

The Political Structure of UK Broadcasting 1949-1999 Elstein, David

www.ssoar.info The political structure of UK broadcasting 1949-1999 Elstein, David Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Monographie / monograph Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Elstein, D. (2015). The political structure of UK broadcasting 1949-1999. (Media, Democracy & Political Process Series). Lüneburg: meson press. https://doi.org/10.14619/011 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-SA Lizenz (Namensnennung- This document is made available under a CC BY-SA Licence Weitergabe unter gleichen Bedingungen) zur Verfügung gestellt. (Attribution-ShareAlike). For more Information see: Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.de David Elstein POLITICAL The Political Structure of UK Broadcasting 1949-1999 STRUCTURE BROADCASTING UK ELSTEIN The Political Structure of UK Broadcasting 1949-1999 Media, Democracy & Political Process Series Edited by Christian Herzog, Volker Grassmuck, Christian Heise and Orkan Torun The Political Structure of UK Broadcasting 1949-1999 David Elstein Bibliographical Information of the German National Library The German National Library lists this publication in the Deutsche National bibliografie (German National Biblio graphy); detailed bibliographic information is available online at http://dnb.dnb.de Published in 2015 by meson press, Hybrid Publishing Lab, Centre for Digital Cultures, Leuphana University of Lüneburg www.mesonpress.com Design concept: Torsten Köchlin, Silke Krieg Cover Image: Sebastian Mühleis and Christian Herzog The print edition of this book is printed by Lightning Source, Milton Keynes, United Kingdom ISBN (Print): 9783957960603 ISBN (PDF): 9783957960610 ISBN (EPUB): 9783957960627 DOI: 10.14619/011 The digital editions of this publication can be downloaded freely at: www.mesonpress.com Funded by the EU major project Innovation Incubator Lüneburg This Publication is licensed under the CCBYSA 4.0 Inter national. -

Appendix List of Interviews*

Appendix List of Interviews* Name Date Personal Interview No. 1 29 August 2000 Personal Interview No. 2 12 September 2000 Personal Interview No. 3 18 September 2000 Personal Interview No. 4 6 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 5 16 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 6 17 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 7 18 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 8: Oonagh Marron (A) 17 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 9: Oonagh Marron (B) 23 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 10: Helena Schlindwein 28 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 11 30 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 12 1 November 2000 Personal Interview No. 13 1 November 2000 Personal Interview No. 14: Claire Hackett 7 November 2000 Personal Interview No. 15: Meta Auden 15 November 2000 Personal Interview No. 16 1 June 2000 Personal Interview Maggie Feeley 30 August 2005 Personal Interview No. 18 4 August 2009 Personal Interview No. 19: Marie Mulholland 27 August 2009 Personal Interview No. 20 3 February 2010 Personal Interview No. 21A (joint interview) 23 February 2010 Personal Interview No. 21B (joint interview) 23 February 2010 * Locations are omitted from this list so as to preserve the identity of the respondents. 203 Notes 1 Introduction: Rethinking Women and Nationalism 1 . I will return to this argument in a subsequent section dedicated to women’s victimisation as ‘women as reproducers’ of the nation. See also, Beverly Allen, Rape Warfare: The Hidden Genocide in Bosnia-Herzegovina (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1996); Alexandra Stiglmayer, (ed.), Mass Rape: The War Against Women in Bosnia- Herzegovina (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 1994); Carolyn Nordstrom, Fieldwork Under Fire: Contemporary Studies of Violence and Survival (Berkeley: University of California, 1995); Jill Benderly, ‘Rape, feminism, and nationalism in the war in Yugoslav successor states’ in Lois West, ed., Feminist Nationalism (London and New Tork: Routledge, 1997); Cynthia Enloe, ‘When soldiers rape’ in Maneuvers: The International Politics of Militarizing Women’s Lives (Berkeley: University of California, 2000). -

Copyright by Joseph Paul Moser 2008

Copyright by Joseph Paul Moser 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Joseph Paul Moser certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Patriarchs, Pugilists, and Peacemakers: Interrogating Masculinity in Irish Film Committee: ____________________________ Elizabeth Butler Cullingford, Co-Supervisor ____________________________ Neville Hoad, Co-Supervisor ____________________________ Alan W. Friedman ____________________________ James N. Loehlin ____________________________ Charles Ramírez Berg Patriarchs, Pugilists, and Peacemakers: Interrogating Masculinity in Irish Film by Joseph Paul Moser, M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2008 For my wife, Jennifer, who has given me love, support, and the freedom to be myself Acknowledgments I owe many people a huge debt for helping me complete this dissertation. Neville Hoad gave me a crash course in critical theory on gender; James Loehlin offered great feedback on the overall structure of the study; and Alan Friedman’s meticulous editing improved my writing immeasurably. I am lucky to have had the opportunity to study with Charles Ramírez Berg, who is as great a teacher and person as he is a scholar. He played a crucial role in shaping the chapters on John Ford and my overall understanding of film narrative, representation, and genre. By the same token, I am fortunate to have worked with Elizabeth Cullingford, who has been a great mentor. Her humility, wit, and generosity, as well as her brilliance and tenacity, have been a continual source of inspiration. -

Socialist Lawyer 58

Lawyer SocialistMagazine of the Haldane Society of Socialist Lawyers n Number 58 l June 2011 £3 Inside: DEFEND INTERVIEW LEGAL AID: ‘T-PIMS’ – CONSCIENTIOUS THE WITH WOMEN CONTROL OBJECTORS RIGHT TO GARETH DEMAND ORDERS AND THE UK PROTEST PEIRCE RIGHTS LITE? MILITARYand more... Haldane Society PO Box 64195, London WC1A 9FD Website: www.haldane.org Contents Number 58 June 2011 ISSN 09 54 3635 News & comment ................................................................................ 4 Haldane talks, EDL in Luton, TUC in March, Blair’s legacy, Sedley’s send-off and more Inquiringly like-minded ...................................................... 11 Regular column from the Young Legal Aid Lawyers, with Connor Johnston Kettling and criminalising protest .......... 12 Kat Craig on the use of increasingly violent and oppressive tactics by the police Defending the right to protest ........................ 16 Fiona McPhail on the recent rebirth of protest and the legal clampdown The Haldane Society was founded in 1930. It provides a forum for the discussion and analysis of law and the legal system, both nationally and internationally, from a socialist perspective. It holds frequent public meetings and conducts educational programmes. The Haldane Society is independent of any political party. Membership comprises lawyers, academics, students and legal workers as well as trade union and labour movement affiliates. President: Michael Mansfield QC Vice Presidents: Kader Asmal, Louise Christian, Tony Gifford QC, Tess Gill, John Hendy QC, Helena -

SHARON HOWARD-FIELD 1 Casting Director

SHARON HOWARD-FIELD 1 Casting Director EMPLOYMENT HISTORY: • Howard-Field Casting, (Los Angeles, London & Europe) 1993-2014 • Director of Feature Casting, Warner Bros. Studios, Los Angeles 1989-1993 • Howard-Field Casting ( London & Europe) 1983-1989 • Casting & Project Consultant RKO, London operations 1983-1985 • Associate Casting Director Royal Shakespeare Company, London 1977-1983 • Production Assistant to director/producer Martin Campbell, London 1975-1977 • Assistant to writer, Tudor Gates, Drumbeat Productions, London 1975-1977 FILMS CURRENTLY IN DEVELOPMENT FOR 2014/15: AMOK – Director: Kasia Adamik. Screenplay: Richard Karpala. Executive producer: Agnieszka Holland. Producers: Beata Pisula, Debbie Stasson - in development for spring 2015 WALKING TO PARIS – Director: Peter Greenaway, Producer: Kees Kasander and Julia Ton. Scheduled to commence pp February 2015 in Romania, Switzerland and France. THE WORLD AT NIGHT – Director: TBC. Screenplay: William Nicholson. Producer: Vanessa van Zuylen, (VVZ Presse, Paris, France), Matthias Ehrenberg, Jose Levy, (Cuatro Films Plus) Ibon Cormenzana, (Arcadia Motion Pictures), – in development to shoot Argentina and France Spring 2015. Daniel Bruhl attached. RACE – In association with Suzanne Smith Casting. Director: Stephen Hopkins. Filming Berlin and Canada, September 2014. Casting a selection of cameo roles from the UK AMERICAN MASSACRE – Director: TBC Producer: Emjay Rechsteiner (Staccato Films); Executive Producer: Harris Tulchin - in development for Spring 2015, shooting New Zealand and Canary Islands LITTLE SECRET (Pequeno Segredo) – Director: David Schurmann; Writer: Marcos Bernstein; Producers: Matthias Ehrenberg (Cuatro Films Plus), Joao, Roni (Ocean Films, Brazil), Emma Slade (Fire Fly Films, NZ), Barrie Osborn – in development to shoot Brazil, October 2014. Finnoula Flanagan attached THE BAY OF SILENCE: - Director: Mark Pellington; Screenwriter & Producer: Caroline Goodall, Executive Producer: Peter Garde.