A History of Tennessee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the PDF of Jubilee Centers in the Episcopal Church in East Tennessee

Diocese of East Tennessee Jubilee Centers DIOCESAN JUBILEE OFFICER – DIOCESE OF EAST TENNESSEE Cameron Ellis Phone: 865-414-5742 E-mail: [email protected] For questions or applying to be a center, or copies, please contact me. Middle East Region – Knoxville CHURCH OF THE GOOD SHEPHERD – KNOXVILLE Designated November, 2015 (Sponsor – Church of the Good Shepherd – Knoxville) 5409 Jacksboro Pike, Knoxville, TN 37918 ………………………………………..Ph: 865-687-9420 E-mail: [email protected] ………………………………………………Fax: 865-689-7056 Website: http://goodshepherdknoxville.org/ Becky Blankenbeckler, Program Director The Church of the Good Shepherd has an exceptional outreach program consisting of many ministries and mission trips that are applicable for all ages. To support these ministries, they conduct very creative “FUN”draising events such as Ladies Tea and Fashion Show, Coach Bag Bingo, and special collections of food and money for specific projects e.g. preparing and packaging 10,000 meals to feed the hungry in Guatemala; and 20,000 meals to serve in the 18 county radius. They offer a FISH Food pantry, Deliver Mobile Meals, build wheelchair ramps at homes serving those with Cerebral Palsy and the elderly, etc. There are too many ministries to list in this brief space, but please visit their website or speak with a member, or Becky, or The Rev. Ken Asel. Middle East Region – Knoxville ST. JAMES FEEDING MINISTRIES Re-commissioned June 2011 Designated June 2002 (Sponsor – St. James – Knoxville) 1101 Broadway NE Knoxville TN 37917 ..........................................................................................................Ph: 865.523.5687 E-mail: [email protected] ......................................................................................................................Fax: 865.522.2979 Website: http://stjamesknox.dioet.org/ Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/pages/St-James-Episcopal-Church-of-Knoxville Contact: The Rev. -

USSYP 2013 Yearbook

THE HEARST FOUNDATIONS DIRECTORS William Randolph Hearst III PRESIDENT James M. Asher Anissa B. Balson UNITED STATES SENATE YOUTH PROGRAM David J. Barrett Frank A. Bennack, Jr. John G. Conomikes Ronald J. Doerfl er Lisa H. Hagerman George R. Hearst III Gilbert C. Maurer Mark F. Miller Virginia H. Randt Steven R. Swartz Paul “Dino” Dinovitz EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR George B. Irish EASTERN DIRECTOR Rayne B. Guilford PROGRAM DIRECTOR FIFTY-FIRST ANNUAL WASHINGTON WEEK 2013 Lynn De Smet DEPUTY DIRECTOR Catherine Mahoney PROGRAM MANAGER Hayes Reisenfeld PROGRAM LIAISON UNITED STATES SENATE YOUTH PROGRAM FIFTY-FIRST ANNUAL WASHINGTON WEEK ! MARCH 9–16, 2013 SPONSORED BY THE UNITED STATES SENATE FUNDED AND ADMINISTERED BY THE THE HEARST FOUNDATIONS 90 NEW MONTGOMERY STREET ! SUITE 1212 ! SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94105"4504 WWW.USSENATEYOUTH.ORG Photography by Jakub Mosur Secondary Photography by Erin Lubin Design by Catalone Design Co. USSYP_31_Yearbook_COV_052313_cc.indd 1 5/29/13 4:04 PM Forget conventionalisms; forget what the world thinks of you stepping out of your place; think your best thoughts, speak your best words, work your best works, looking to your own conscience for approval. SUSAN B. ANTHONY USSYP_31_Yearbook_COV_052313_cc.indd 2 5/24/13 3:33 PM 2013 UNITED STATES SENATE YOUTH PROGRAM SENATE ADVISORY COMMITTEE HONORARY CO-CHAIRS VICE PRESIDENT SENATOR SENATOR JOSEPH R. BIDEN HARRY REID MITCH McCONNELL President of the Senate Majority Leader Republican Leader CO-CHAIRS SENATOR JEANNE SENATOR SHAHEEN RICHARD BURR of New Hampshire of North Carolina -

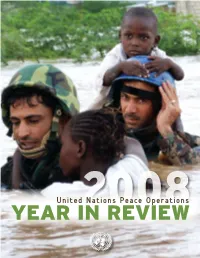

Year in Review 2008

United Nations Peace Operations YEAR IN2008 REVIEW asdf TABLE OF CONTENTS 12 ] UNMIS helps keep North-South Sudan peace on track 13 ] MINURCAT trains police in Chad, prepares to expand 15 ] After gaining ground in Liberia, UN blue helmets start to downsize 16 ] Progress in Côte d’Ivoire 18 ] UN Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea is withdrawn 19 ] UNMIN assists Nepal in transition to peace and democracy 20 ] Amid increasing insecurity, humanitarian and political work continues in Somalia 21 ] After nearly a decade in Kosovo, UNMIK reconfigures 23 ] Afghanistan – Room for hope despite challenges 27 ] New SRSG pursues robust UN mandate in electoral assistance, reconstruction and political dialogue in Iraq 29 ] UNIFIL provides a window of opportunity for peace in southern Lebanon 30 ] A watershed year for Timor-Leste 33 ] UN continues political and peacekeeping efforts in the Middle East 35 ] Renewed hope for a solution in Cyprus 37 ] UNOMIG carries out mandate in complex environment 38 ] DFS: Supporting peace operations Children of Tongo, Massi, North Kivu, DRC. 28 March 2008. UN Photo by Marie Frechon. Children of Tongo, 40 ] Demand grows for UN Police 41 ] National staff make huge contributions to UN peace 1 ] 2008: United Nations peacekeeping operations observes 60 years of operations 44 ] Ahtisaari brings pride to UN peace efforts with 2008 Nobel Prize 6 ] As peace in Congo remains elusive, 45 ] Security Council addresses sexual violence as Security Council strengthens threat to international peace and security MONUC’s hand [ Peace operations facts and figures ] 9 ] Challenges confront new peace- 47 ] Peacekeeping contributors keeping mission in Darfur 48 ] United Nations peacekeeping operations 25 ] Peacekeepers lead response to 50 ] United Nations political and peacebuilding missions disasters in Haiti 52 ] Top 10 troop contributors Cover photo: Jordanian peacekeepers rescue children 52 ] Surge in uniformed UN peacekeeping personnel from a flooded orphanage north of Port-au-Prince from1991-2008 after the passing of Hurricane Ike. -

Film 2466 Guide the Papers in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division the Papers of Henry Clay 1770 – 1852 in 34 Volumes Reel 1

Film 2466 Guide The Papers in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division The Papers of Henry Clay 1770 – 1852 in 34 volumes Reel 1 v.1-5 1770:Nov.30-1825:Oct.12 Reel 2 v.6-10 1825:Oct.13-1827:Oct.21 Reel 3: v.11-15 1827:Oct.22-1829:Nov.11 Reel 4 v.16-19 1829:Nov.13-1832:Aug.24 Reel 5 v.20-23 1832:Aug.26-1844:Oct.4 Reel 6 v.24-26, v.27 1844:Oct.9-1852:Nov.4, Undated papers Reel 7 v.1-4 1825:Mar.10-1826:Nov.8 1 Reel 8 v.5-7 1826:Nov.11-1829:Feb.28 Reel 9 Papers of Henry Clay And Miscellaneous Papers 1808-1853 1. Henry Clay Papers (Unbound) 2. Personal Miscellany 3. Photostat Miscellany 4. Slave Papers 5. United States: Executive (Treaty of Ghent) 6. United States: Executive (North East Boundary) 7. Finance (Unarranged) 8. Finance (United States Bank) 9. United States Miscellany Reel 10 v.3: Selected Documents Nov. 6, 1797- Aug. 11, 1801 v.4: Selected Documents Aug. 18, 1801-Apr. 10, 1807 2 Reel 10 (continued) The Papers of Thomas J. Clay 1737-1927 In 33 volumes v.5: July 14, 1807 – Nov.26, 1817 v.6 Dec.23, 1817-June 3, 1824 There does not appear to be anything to this volume. v.7 June 25, 1824 – Aug. 20, 1830 v.8 Aug. 27, 1830 – July 20, 1837: The Papers of Thomas J. Clay v.9:Aug. 14, 1837-Jan. 21, 1844: The Papers of Thomas J. -

James Knox Polk Collection, 1815-1949

State of Tennessee Department of State Tennessee State Library and Archives 403 Seventh Avenue North Nashville, Tennessee 37243-0312 POLK, JAMES KNOX (1795-1849) COLLECTION 1815-1949 Processed by: Harriet Chapell Owsley Archival Technical Services Accession Numbers: 12, 146, 527, 664, 966, 1112, 1113, 1140 Date Completed: April 21, 1964 Location: I-B-1, 6, 7 Microfilm Accession Number: 754 MICROFILMED INTRODUCTION This collection of James Knox Polk (1795-1849) papers, member of Tennessee Senate, 1821-1823; member of Tennessee House of Representatives, 1823-1825; member of Congress, 1825-1839; Governor of Tennessee, 1839-1841; President of United States, 1844-1849, were obtained for the Manuscripts Section by Mr. and Mrs. John Trotwood Moore. Two items were given by Mr. Gilbert Govan, Chattanooga, Tennessee, and nine letters were transferred from the Governor’s Papers. The materials in this collection measure .42 cubic feet and consist of approximately 125 items. There are no restrictions on the materials. Single photocopies of unpublished writings in the James Knox Polk Papers may be made for purposes of scholarly research. SCOPE AND CONTENT The James Knox Polk Collection, composed of approximately 125 items and two volumes for the years 1832-1848, consist of correspondence, newspaper clippings, sketches, letter book indexes and a few miscellaneous items. Correspondence includes letters by James K. Polk to Dr. Isaac Thomas, March 14, 1832, to General William Moore, September 24, 1841, and typescripts of ten letters to Major John P. Heiss, 1844; letters by Sarah Polk, 1832 and 1891; Joanna Rucker, 1845- 1847; H. Biles to James K. Polk, 1833; William H. -

A Tri-Annual Publication of the East Tennessee Historical Society

Vol. 26, No. 2 August 2010 Non-Profit Org. East Tennessee Historical Society U.S. POStage P.O. Box 1629 PAID Knoxville, TN 37901-1629 Permit No. 341 Knoxville, tenn ANDERSON KNOX BLEDSOE LOUDON BLOUNT MARION BRADLEY McMINN CAMPBELL MEIGS CARTER MONROE CLAIBORNE MORGAN COCKE POLK CUMBERLAND RHEA FENTRESS ROANE GRAINGER GREENE SCOTT HAMBLEN SEQUATCHIE HAMILTON SEVIER HANCOCK SULLIVAN HAWKINS UNICOI A Tri-Annual Publication of JEFFERSON UNION JOHNSON WASHINGTON The East Tennessee Historical Society Heritage Programs from The easT Tennessee hisTorical socieTy Were your ancestors in what is now Tennessee prior to statehood in 1796? If so, you are eligible to join the First The easT Tennessee hisTorical socieTy Families of Tennessee. Members receive a certificate engraved with the name of the applicant and that of the Making history personal ancestor and will be listed in a supplement to the popular First Families of Tennessee: A Register of the State’s Early Settlers and Their Descendants, originally published in 2000. Applicants must prove generation-by-generation descent, as well as pre-1796 residence for the ancestor. The We invite you to join one of the state’s oldest and most active historical societies. more than 14,000 applications and supporting documentation comprise a unique collection of material on our state’s earliest settlers and are available to researchers at the McClung Historical Collection in the East Members receive Tennessee History Center, 601 S. Gay St. in downtown Knoxville. • Tennessee Ancestors—triannual genealogy -

Application for the TENNESSEE GOVERNOR's SCHOOLS for The

Application for the TENNESSEE GOVERNOR’S SCHOOLS for the Agricultural Sciences Business and IT Leadership Computational Physics Emerging Technologies Engineering Humanities International Studies Prospective Teachers Sciences Scientific Exploration of Tennessee Heritage Scientific Models and Data Analysis Tennessee State Department of Education Nashville, Tennessee Summer 2014 ED-2716 (Rev 10-12) C A THE GOVERNOR’S SCHOOLS OF TENNESSEE 1. The School for the Agricultural Sciences ( May 31-June 27, 2014), which is held on the campus of The University of Tennessee at Martin, focuses on the importance of agriculture to the state and national economy. Emphasis is placed on experiential learning and laboratory exercises related to the agricultural sciences to include production agriculture, agricultural business enterprises and natural resources management. Application deadline: postmarked by Dec. 7, 2013. http://www.utm.edu/departments/caas/tgsas/ 2. The School for the Arts (June 1 -June 26, 2014) will be held on the campus of Middle Tennessee State University in Murfreesboro—only 30 miles from Nashville and the Tennessee Performing Arts Center, the Schermerhorn Symphony Center, Cheekwood Fine Arts Center, and world famous recording studios. This year’s application deadline for the School for the Arts has changed to Nov. 6, 2013. A separate application for the School of the Arts is available on their website. http://www.gsfta.com/ 3. The School for B u s i n e s s a n d I T Leadership ( May 3 1- June 28 , 2014) will be held on the campus of Tennessee Technological University in Cookeville. Students will enhance their knowledge of information technology and business leadership by developing a business plan for an information technology- based business. -

Chapter 2: Struggle for the Frontier Quiz

Chapter 2: Struggle for the Frontier Quiz 1. Which of the following tribes lived or hunted in Tennessee? (Select all that apply) a. Cherokee b. Shawnee c. Iroquois d. Creek e. Chickasaw 2. What is Cumberland Gap? a. A low area between the mountains that allowed travelers to cross the mountains more easily b. A trail cut by Richard Henderson through the mountains c. An early settlement in Tennessee d. A mountain peak between Tennessee and Kentucky 3. During the French and Indian War, the British built which Fort in an effort to keep the Cherokee loyal to their side? (Choose 1) a. Fort Nashborough b. Fort Donelson c. Fort Watauga d. Fort Loudoun 4. Choose one answer to complete this sentence: The Proclamation of 1763… a. Ended fighting between the British and the French. b. Prohibited settlements beyond the Appalachian Mountains in an effort to avoid further conflict with Native Americans. c. Was an agreement among the Cherokee about how to deal with the settlers. d. Ended the French and Indian War. Tennessee Blue Book: A History of Tennessee- Student Edition https://tnsoshistory.com 5. Why did the Watauga settlers create the Watauga Compact in 1772? a. Their settlement was under attack by the Cherokee b. Their settlement was outside the boundaries of any colony c. Their settlement was under the control of the British government d. Their settlement needed a more efficient system of government 6. Who cut the trail known as the Wilderness Road? a. James Robertson b. John Donelson c. Daniel Boone d. John Sevier 7. -

No.75 an Order Renaming the Tennessee Emergency Response Council As the State Emergency Response Commission and Replacing Executive Order No

University of Memphis University of Memphis Digital Commons Executive Orders Bill Haslam (2011-2019) 1-1-2019 No.75 An Order Renaming The Tennessee Emergency Response Council As The State Emergency Response Commission And Replacing Executive Order No. 7 Dated April 1, 1987 Bill Haslam Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.memphis.edu/govpubs-tn-governor-bill- haslam-eo Recommended Citation Haslam, Bill, "No.75 An Order Renaming The Tennessee Emergency Response Council As The State Emergency Response Commission And Replacing Executive Order No. 7 Dated April 1, 1987" (2019). Executive Orders. 75. https://digitalcommons.memphis.edu/govpubs-tn-governor-bill-haslam-eo/75 This Executive Order is brought to you for free and open access by the Bill Haslam (2011-2019) at University of Memphis Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Executive Orders by an authorized administrator of University of Memphis Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. (Ji,...'t l.i\' i \ !. ' .• , ~ 20\9 .Jr.N -·7 Mi g: 4 I c[ (" t 'r~ ~,·;, ~1, Y t .• \-- STATE ...) I \ •• • ... ,.,,, • I C' \''\ Ir\ !". '' . _r , , STATE OF TENNESSEE EXECUTIVE ORDER BY THE GOVERNOR No. 75 AN ORDER RENAMING THE TENNESSEE EMERGENCY RESPONSE COUNCIL AS THE STATE EMERGENCY RESPONSE COMMISSION AND REPLACING EXECUTIVE ORDER NO. 7 DATED APRIL 1, 1987 WHEREAS, the proliferation of hazardous materials poses a significant risk to the public's health, safety, and welfare unless responsible planning and coordination measures are instituted; and WHEREAS, to address such risks and promote health, safety, and public welfare, the Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act of 1986, Title III, "Emergency Planning and Community Right-To-Know Act of 1986", codified at 42 U.S.C. -

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Authorized ...z w ~ ~ ~ w C ..... Z w ~ oQ. -'w >w Public Disclosure Authorized C -' -ct ou V') Public Disclosure Authorized " Public Disclosure Authorized VIOLENCE PREVENTION A Critical Dimension of Development Background 2 Agenda 4 Participant Biographies 10 Photo Contest Imagining Peace 32 Photo Contest Winners 33 Photo Contest Finalists 36 Conference Organizing Team & Contact Information 43 The Conflict, Crime and Violence team in the Social high levels of violent crime, street violence, do Development Department (SDV) has organized a mestic violence, and other kinds of violence. day and a half event focusing on "Violence Pre vention: A Critical Dimension of Development". Violence takes many forms: from the traditional As the issue of violence crosscuts other agendas protection racket by illegal organizations to the of the World Bank, the objectives of the event are rise of international illegal trafficking (arms, hu to raise World Bank staff's awareness of the link mans, drugs), from gang-based urban violence between violence prevention and development, its and crime to politically-motivated violence fueled relevance for development, and to present the ra by socio-economic grievances. All these forms of tionale for increased attention to violence preven violence concur to erode the well-being of all- and tion and reduction within World Bank operations. more acutely of the poorest - and to stymie devel opment efforts. Social failure, weak institutional Violence has become one of the most salient de capacity and the lack of a legal framework to pro velopmental issues in the global agenda. Its nega tect and guarantee people's safety and rights cre tive impact on social and economic development ate a climate of lawlessness and engender dynam in countries across the world has been well doc ics of state-within-state behavior by increasingly umented. -

Take the Effective June 2016

2016-2017 Take the EFFECTIVE JUNE 2016 A comprehensive guide to touring Nashville attractions riding MTA buses and the Music City Star. For schedules and other information, visit NashvilleMTA.org or call (615) 862-5950. Nashville MTA & RTA @Nashville_MTA RIDE ALL DAY FOR $5.25 OR LESS Purchase at Music City Central, from the driver, or online at NashvilleMTA.org Take the The Nashville MTA is excited to show you around Music City, whether you’re visiting us for the first time, fifth time, or even if you’re a Middle Tennessee resident enjoying hometown attractions. There’s so much to see and do, and the MTA bus system is an easy, affordable way to see it all. We operate a free downtown service, the Music City Circuit, which is designed to help you reach sports and entertainment venues, downtown hotels, residences, and offices more quickly and easily. The Blue and Green Circuits operate daily with buses traveling to the Bicentennial Mall and the Gulch, a LEED certified community. The Music City Circuit connects many key downtown destinations including the Farmers’ Market, First Tennessee Park, Schermerhorn Symphony Center, Riverfront Station, and the Gulch’s restaurants, bars and condominium towers and numerous points in between. Of course, there are also our other MTA and regional bus routes throughout Middle Tennessee that can be utilized. You can access them by taking a bus to Music City Central, our downtown transit station. Once there, you’ll see how we’re making public transportation more convenient and comfortable, and how making the most of your Nashville experience is now even easier with the MTA. -

A Comparative Analysis of the Alternative Coming-Of-Age Motion Picture

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2016 Screening Male Crisis: A Comparative Analysis of the Alternative Coming-of-Age Motion Picture Matthew J. Tesoro The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1447 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Screening Male Crisis: A Comparative Analysis of the Alternative Coming-of-Age Motion Picture By Matthew Tesoro A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 MATTHEW TESORO All Rights Reserved ii Screening Male Crisis: A Comparative Analysis of the Alternative Coming-of-Age Motion Picture By Matthew Tesoro This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts ____________ ________________________ Date Robert Singer Thesis Advisor ____________ ________________________ Date Matthew Gold MALS Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Screening Male Crisis: A Comparative Analysis of the Alternative Coming-of- Age Motion Picture By Matthew Tesoro Advisor: Robert Singer This thesis will identify how the principle male character in select film narratives transforms from childhood through his adolescence in multiple locations and historical eras.