Toward the Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Internationalization of the Japanese Yen

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Macroeconomic Linkage: Savings, Exchange Rates, and Capital Flows, NBER-EASE Volume 3 Volume Author/Editor: Takatoshi Ito and Anne Krueger, editors Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-38669-4 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/ito_94-1 Conference Date: June 17-19, 1992 Publication Date: January 1994 Chapter Title: On the Internationalization of the Japanese Yen Chapter Author: Hiroo Taguchi Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c8538 Chapter pages in book: (p. 335 - 357) 13 On the Internationalization of the Japanese Yen Hiroo Taguchi The internationalization of the yen is a widely discussed topic, among not only economists but also journalists and even politicians. Although various ideas are discussed under this heading, three are the focus of attention: First, and the most narrow, is the use of yen by nonresidents. Second is the possibility of Asian economies forming an economic bloc with Japan and the yen at the center. Third, is the possibility that the yen could serve as a nominal anchor for Asian countries, resembling the role played by the deutsche mark in the Euro- pean Monetary System (EMS). Sections 13.1-13.3 of this paper try to give a broad overview of the key facts concerning the three topics, above. The remaining sections discuss the international role the yen could play, particularly in Asia. 13.1 The Yen as an Invoicing Currency Following the transition to a floating exchange rate regime, the percentage of Japan’s exports denominated in yen rose sharply in the early 1970s and con- tinued to rise to reach nearly 40 percent in the mid- 1980s, a level since main- tained (table 13.1). -

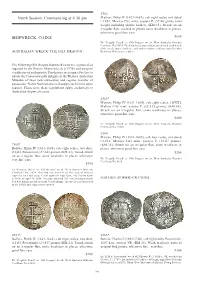

Ninth Session, Commencing at 4.30 Pm SHIPWRECK COINS

2562 Ninth Session, Commencing at 4.30 pm Mexico, Philip IV (1621-1665), cob eight reales, not dated c.1652, Mexico City mint, assayer P, (39.40 grams total weight including plastic holder), (KM.45). Struck on an irregular flan, encased in plastic some weakness in places, otherwise good fine, rare. SHIPWRECK COINS $650 Ex ‘Vergulde Draek’ or ‘Gilt Dragon’ wreck. West Australia Museum Certificate No.10095. The lot includes a specially prepared book, with details of the wreck, maps, certificate, and authentication certificate signed by Alan AUSTRALIAN WRECK ‘THE GILT DRAGON’ Robinson Underwater explorer. The following Gilt Dragon shipwreck coins are registered, as required by the Historic Shipwrecks Act (1976), and assigned certificates of authenticity. Purchasers are required by law to advise the Commonwealth delegate at the Western Australian Museum of their new ownership and register transfer of possession. Noble Numismatics will supply such forms upon request. Please note these regulations apply exclusively to Australian shipwreck coins. 2563* Mexico, Philip IV (1621-1665), cob eight reales, 16[XX], Mexico City mint, assayer P, (25.515 grams), (KM.45). Struck on an irregular flan, some weakness in places, otherwise good fine, rare. $400 Ex ‘Vergulde Draek’ or ‘Gilt Dragon’ wreck. West Australia Museum Certificate No.12835. 2564 Mexico, Philip IV (1621-1665), cob four reales, not dated c.1652, Mexico City mint, assayer P, (13.07 grams), 2560* (KM.38). Struck on an irregular flan, some weakness in Bolivia, Philip IV (1621-1665), cob eight reales, two date, places, otherwise good fine, rare. (16)53, Potosi mint, (27.643 grams), (KM.21). -

Ninth Session, Commencing at 4.30 Pm

Ninth Session, Commencing at 4.30 pm NEW ZEALAND BANKNOTES TRADING BANK ISSUES 2566* Bank of New South Wales, uniform issue, one pound, with 'Sterling' an uncut sheet of six uniface printer's proofs c1924, not issued, no numbers, imprint of Charles Skipper & East, London, pin hole cancellation 'SPECIMEN/C.SKIPPER & EAST' in two lines on each (Robb C.821; L.434; P.S162s). Extremely fi ne and rare. (6 notes) $6,000 2564 Bank of New South Wales, uniform issue, ten shillings, with 'Sterling' an uncut sheet of six uniface printer's proofs c1924, not issued, no numbers, imprint of Charles Skipper & East, London, pin hole cancellation 'SPECIMEN/C.SKIPPER & EAST' in two lines on each note (Robb C.811; L.433; P.S161s). Two minor tape repairs to selvedge (not affecting the notes), extremely fi ne and rare. (6 notes) $6,000 2567* The Colonial Bank of New Zealand, fi rst issue, printer's proof fi fty pounds, uniface, Christchurch, 187-, imprint of Perkins, Bacon & Co. London, horizontal SPECIMEN stamp below in 'Manager' area, 'for other branches see Altn Bk - May 1875' added in pencil in bottom margin (Robb.G.17; L.-; P.S266). Extremely fi ne. $7,000 Ex Perkins Bacon Archive, Spink (Melbourne) Sale, 23 May 1995 (lot 1087). 2565* Bank of New South Wales, uniform issue, ten shillings, without 'Sterling' an uncut sheet of six uniface printer's proofs c1932, not issued, no numbers, imprint of Charles Skipper & East, London, pin hole cancellation 'SPECIMEN/ C.SKIPPER & EAST' in two lines on each note (Robb C.811; L.433; P.S161s). -

Institutions, Competition, and Capital Market Integration in Japan

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES INSTITUTIONS, COMPETITION, AND CAPITAL MARKET INTEGRATION IN JAPAN Kris J. Mitchener Mari Ohnuki Working Paper 14090 http://www.nber.org/papers/w14090 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 June 2008 A version of this paper is forthcoming in the Journal of Economic History. We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Ronald Choi, Jennifer Combs, Noriko Furuya, Keiko Suzuki, and Genna Tan for help in assembling the data. Mitchener would also like to thank the Institute for Monetary and Economic Studies at the Bank of Japan for its hospitality and generous research support while serving as a visiting scholar at the Institute in 2006, and the Dean Witter Foundation for additional financial support. We also thank conference participants at the BETA Workshop in Strasbourg, France and seminar participants at the Bank of Japan for comments and suggestions. The views presented in this paper are solely those of the authors, and do not necessarily represent those of the Bank of Japan, its staff, or the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2008 by Kris J. Mitchener and Mari Ohnuki. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Institutions, Competition, and Capital Market Integration in Japan Kris J. Mitchener and Mari Ohnuki NBER Working Paper No. -

CANON INC. (Exact Name of the Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM SD SPECIALIZED DISCLOSURE REPORT CANON INC. (Exact name of the registrant as specified in its charter) JAPAN 001-15122 (State or other jurisdiction of (Commission (IRS Employer incorporation or organization) File Number) Identification No.) 30-2, Shimomaruko 3-chome , Ohta-ku, Tokyo 146-8501, Japan (Address of principle executive offices) (Zip code) Eiji Shimizu, +81-3-3758-2111, 30-2, Shimomaruko 3-chome, Ohta-ku, Tokyo 146-8501, Japan (Name and telephone number, including area code, of the person to contact in connection with this report.) Check the appropriate box to indicate the rule pursuant to which this form is being filed and provide the period to which the information in this form applies: Rule 13p-1 under the Securities Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13p-1) for the reporting period from January 1, 2017 to December 31, 2017. Section 1 - Conflict Minerals Disclosure Established in 1937, Canon Inc. is a Japanese corporation with its headquarters in Tokyo, Japan. Canon Inc. is one of the world’s leading manufacturers of office multifunction devices (“MFDs”), plain paper copying machines, laser printers, inkjet printers, cameras, diagnostic equipment and lithography equipment. Canon Inc. earns revenues primarily from the manufacture and sale of these products domestically and internationally. Canon Inc. and its consolidated companies fully have been aware of conflict minerals issue and have been working together with business partners and industry entities to address the issue of conflict minerals. In response to Rule 13p-1, Canon Inc. conducted Reasonable Country of Origin Inquiry and due diligence based on the “OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas,” for its various products. -

Places of Employment of Graduates from Faculty/Graduate School (Master's Program) (FY2015)

Places of Employment of Graduates from Faculty/Graduate School (Master's Program) (FY2015) Faculty of Letters/Graduate School of Humanities ● Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corp. ● Nippon Life Insurance Co. ● Osaka Customs ● Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Bank, Ltd. ● Teacher (JH&HS) ● Kobe Customs ● The Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ, Ltd. ● Hyogo Prefectural High School ● Kobe City Office ● Bank of Japan ● Osaka Regional Taxation Bureau ● Toyonaka City Office ● Japan Post Bank Co., Ltd. ● Japan MINT ● Hiroshima Home Television Co.,Ltd. ● Mizuho Securities Co., Ltd. ● Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology ● Japan Broadcasting Corporation ● Daiwa Securities Co., Ltd. ● Osaka Public Prosecutors Office ● Kobe Steel,Ltd. ● Japan Post Insurance Co.,Ltd. ● Kobe District Court ● Mitsubishi Electric Corp. Faculty of Intercultural Studies/Graduate School of Intercultural Studies ● Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan ● Nippon Life Insurance Company ● Toyota Motor Corp. ● Osaka Immigration Bureau ● SUMITOMO LIFE INSURANCE COMPANY ● KANEKA CORPORATION ● Kansai Bureau of Economy ● Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corp. ● Mitsubishi Electric Corp. ● Tokyo Metropolitan Government ● Resona Bank, Ltd. ● New Kansai International Airport Co., Ltd. ● Kobe City Office ● Mizuho Bank, Ltd. ● Daiwa Institute of Research Ltd. ● Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art ● The Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ, Ltd. ● TAISEI CORPORATION ● Kansai Telecasting Corporation ● Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings, Inc. ● Kobe Steel,Ltd. ● Japan Broadcasting Corp. ● THE KANSAI ELECTRIC POWER Co., INC. ● Hitachi, Ltd. Faculty of Human Development/Graduate School of Human Development and Environment ● Suntory Holdings Ltd. ● Mitsubishi Corp. ● Hyogo Prefectural High school ● ASICS Corp. ● Mizuho Bank, Ltd. ● Osaka Prefectural High school ● Kobe Steel,Ltd. ● The Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ, Ltd. ● Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare ● Murata Manufacturing Co., Ltd. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 324 International Conference on Architecture: Heritage, Traditions and Innovations (AHTI 2019) Exploration on the Protection Scheme of the Great Ruins of Southern Lifang District in the Luoyang City Site in Sui and Tang Dynasties Haixia Liang Luoyang Institute of Science and Technology Luoyang, China Peiyuan Li Zhenkun Wang Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology China Petroleum First Construction Company (Luoyang) Xi'an, China Luoyang, China Abstract—The great ruins are a kind of non-renewable district in a comprehensive and detailed way. Through the precious resources. The southern Lifang district in the analysis of the current situation of southern Lifang district, a Luoyang City Site in Sui and Tang Dynasties is the product of relatively reasonable planning proposal is obtained. This the development of ancient Chinese capital to a certain study can provide theoretical or practical reference and help historical stage. As many important relics and rich cultural on the protection and development of Luoyang City Site in history have been excavated here, the district has a rich Sui and Tang Dynasties, as well as the reconstruction of humanity history. In the context of the ever-changing urban southern Lifang district. construction, the protection of the great ruins in the district has become more urgent. From the point of view of the protection of the great ruins, this paper introduces the II. GREAT RUINS, SUI AND TANG DYNASTIES, LUOYANG important sites and cultural relics of southern Lifang district CITY AND LIFANG DISTRICT in Luoyang city of the Sui and Tang Dynasties through field Great ruins refer to large sites or groups of sites with a investigation and literature review. -

9. Ceramic Arts

Profile No.: 38 NIC Code: 23933 CEREMIC ARTS 1. INTRODUCTION: Ceramic art is art made from ceramic materials, including clay. It may take forms including art ware, tile, figurines, sculpture, and tableware. Ceramic art is one of the arts, particularly the visual arts. Of these, it is one of the plastic arts. While some ceramics are considered fine art, some are considered to be decorative, industrial or applied art objects. Ceramics may also be considered artifacts in archaeology. Ceramic art can be made by one person or by a group of people. In a pottery or ceramic factory, a group of people design, manufacture and decorate the art ware. Products from a pottery are sometimes referred to as "art pottery".[1] In a one-person pottery studio, ceramists or potters produce studio pottery. Most traditional ceramic products were made from clay (or clay mixed with other materials), shaped and subjected to heat, and tableware and decorative ceramics are generally still made this way. In modern ceramic engineering usage, ceramics is the art and science of making objects from inorganic, non-metallic materials by the action of heat. It excludes glass and mosaic made from glass tesserae. There is a long history of ceramic art in almost all developed cultures, and often ceramic objects are all the artistic evidence left from vanished cultures. Elements of ceramic art, upon which different degrees of emphasis have been placed at different times, are the shape of the object, its decoration by painting, carving and other methods, and the glazing found on most ceramics. 2. -

Noritake Garden Entrance Exit Fascinating Cycle of Life up Close

天 Parking Lot Encounter nature at the biotope 1F A biotope is an area in an urban setting that provides oritae uare aoa C a living environment for plants, insects, sh, birds, iestle so Parking Gate and other forms of life. Come experience the General Discover the Culture, Rest in the Forest. Noritake Garden Entrance Exit fascinating cycle of life up close. Information See everything Noritake and Enjoy lunch and dessert served Free Admission (Admission fees apply for the Craft Center and Noritake Museum only) Okura Art China have to offer, on casual Noritake tableware. The Enormous “Six Chimneys” “The Detached Kiln” * All facilities are barrier-free. from elegant daily-use tableware Come and take a break from A monument symbolizing instills visitors with a sense to prestige products. A full lineup shopping or walking. Admission fees for the Craft Center and Noritake Museum of tableware is also available. Noritake’s dream the enthusiasm of its time. Adults/university students 500 yen These are relics from the tunnel This old kiln, nestled amidst a Visitors aged 65 or over 300 yen North Gate Nishi-Yabushita kilns built in 1933 to bake quiet forest, exudes the High school students and younger Free Discover the Culture, Rest in the Forest. Visitors with ID verifying disability Free CRAFT CENTER ceramics. The Noritake dream, a enthusiasm of the soil and Pedestrian access constant beacon of inspiration ames from its time. (Be prepared to present the ID) Noritake Museum * Group discounts available Groups of 30 or more 10% off Noritake Garden The “Red Brick Buildings”, ever since the early Meiji Period, Groups of 100 or more 20% off 4F Admire the grand “Old Noritake” symbolic of Japan’s burns on bright today. -

Japanese Monetary Policy and the Yen: Is There a “Currency War”? Robert Dekle and Koichi Hamada

Japanese Monetary Policy and the Yen: Is there a “Currency War”? Robert Dekle and Koichi Hamada Department of Economics USC Department of Economics Yale University April 2014 Very Preliminary Please do not cite or quote without the authors’ permission. All opinions expressed in this paper are strictly those of the authors and should not necessarily be attributed to any organizations the authors are affiliated with. We thank seminar participants at the University of San Francisco, the Development Bank of Japan, and the Policy Research Institute of the Japanese Ministry of Finance for helpful comments. Abstract The Japanese currency has recently weakened past 100 yen to the dollar, leading to some criticism that Japan is engaging in a “currency war.” The reason for the recent depreciation of the yen is the expecta- tion of higher inflation in Japan, owing to the rapid projected growth in Japanese base money, the sum of currency and commercial banking reserves at the Bank of Japan. Hamada (1985) and Hamada and Okada (2009) among others argue that in general, the expansion of the money supply or the credible an- nouncement of a higher inflation target does not necessarily constitute a “currency war”. We show through our empirical analysis that expan- sionary Japanese monetary policies have generally helped raise U.S. GDP, despite the appreciation of the dollar. 1 Introduction. The Japanese currency has recently weakened past 100 yen to the dollar, leading to criticism that Japan is engaging in a “currency war.” The reason for the recent depreciation of the yen is the expectation of higher inflation in Japan, owing to the rapid projected growth in Japanese base money, the sum of currency and commercial banking reserves at the Bank of Japan. -

Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2014 Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan Laura Nuffer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian Studies Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Nuffer, Laura, "Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan" (2014). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1389. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1389 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1389 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan Abstract Interspecies marriage (irui kon'in) has long been a central theme in Japanese literature and folklore. Frequently dismissed as fairytales, stories of interspecies marriage illuminate contemporaneous conceptions of the animal-human boundary and the anxieties surrounding it. This dissertation contributes to the emerging field of animal studies yb examining otogizoshi (Muromachi/early Edo illustrated narrative fiction) concerning elationshipsr between human women and male mice. The earliest of these is Nezumi no soshi ("The Tale of the Mouse"), a fifteenth century ko-e ("small scroll") attributed to court painter Tosa Mitsunobu. Nezumi no soshi was followed roughly a century later by a group of tales collectively named after their protagonist, the mouse Gon no Kami. Unlike Nezumi no soshi, which focuses on the grief of the woman who has unwittingly married a mouse, the Gon no Kami tales contain pronounced comic elements and devote attention to the mouse-groom's perspective. -

Unit 6 Unit 6

Book UnitUnit 66 33 pp.38-39 Who is taller? Aims for this lesson To learn usage of comparatives and superlatives To eliminate the bias of height and gender To ask appropriate questions to get information and solve a task Target sentences Words I am tall. I am taller. I am the tallest. tall → taller, long → longer, short → shorter, The “note” box on the textbook left-hand page introduces big → bigger, small → smaller, strong → stronger, new grammar with illustrations. It is not necessary to teach good → better, bad → worse students English grammar using special grammatical terms. What to prepare ●Class Cards: Unit6-3 #113-120 (comparatives) Verbal phrases: tall→taller, long→longer, short→shorter, big→bigger, small→smaller, tall / taller strong→stronger, good→better, bad→worse ●Card Plus+: Unit 6-3 #242-245 (superlatives) ( the tallest, the shortest, the biggest, the strongest) the tallest the strongest ●Activity Sheets ●Activity Sheets “Which snake is longer?” “Who is taller, the father or the mother?” ※Fold bottom up twice along the dotted ※Cut up #66 into mini-cards. lines of #63, 64 and 65. ※Attach magnets to the back of 6 A4 Sheets #63 (No.1) length comparisons of snakes (# 67-72). #64 (No.2) size comparisons of houses #65 (No.3) height comparisons of three children Warm up and Review 1 Greet the class. 2 Q&A (No.1-48) : See the “70 Questions List for Book 3”. 3 Review the previous lesson: Unit 6-2 p.36 Play CD2 #9. Have students repeat the words in the ‘Words’ box. Play CD2 #10.