4Th Proceeding 2019-20

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District Wise Skill Gap Study for the State of Haryana.Pdf

District wise skill gap study for the State of Haryana Contents 1 Report Structure 4 2 Acknowledgement 5 3 Study Objectives 6 4 Approach and Methodology 7 5 Growth of Human Capital in Haryana 16 6 Labour Force Distribution in the State 45 7 Estimated labour force composition in 2017 & 2022 48 8 Migration Situation in the State 51 9 Incremental Manpower Requirements 53 10 Human Resource Development 61 11 Skill Training through Government Endowments 69 12 Estimated Training Capacity Gap in Haryana 71 13 Youth Aspirations in Haryana 74 14 Institutional Challenges in Skill Development 78 15 Workforce Related Issues faced by the industry 80 16 Institutional Recommendations for Skill Development in the State 81 17 District Wise Skill Gap Assessment 87 17.1. Skill Gap Assessment of Ambala District 87 17.2. Skill Gap Assessment of Bhiwani District 101 17.3. Skill Gap Assessment of Fatehabad District 115 17.4. Skill Gap Assessment of Faridabad District 129 2 17.5. Skill Gap Assessment of Gurgaon District 143 17.6. Skill Gap Assessment of Hisar District 158 17.7. Skill Gap Assessment of Jhajjar District 172 17.8. Skill Gap Assessment of Jind District 186 17.9. Skill Gap Assessment of Kaithal District 199 17.10. Skill Gap Assessment of Karnal District 213 17.11. Skill Gap Assessment of Kurukshetra District 227 17.12. Skill Gap Assessment of Mahendragarh District 242 17.13. Skill Gap Assessment of Mewat District 255 17.14. Skill Gap Assessment of Palwal District 268 17.15. Skill Gap Assessment of Panchkula District 280 17.16. -

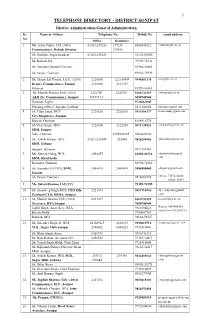

1 TELEPHONE DIRECTORY - DISTRICT SONIPAT District Administration/General Administration Sr

1 TELEPHONE DIRECTORY - DISTRICT SONIPAT District Administration/General Administration Sr. Name of Officer Telephone No. Mobile No. email address No. Office Residence 1. Ms. Anita Yadav, IAS (2004) 01262-255253 279233 8800540222 [email protected] Commissioner, Rohtak Division 274555 Sh. Gulshan, Superintendent 01262-255253 94163-80900 Sh. Rakesh, PA 99925-72241 Sh. Surender, Reader/Commnr. 98964-28485 Sh. Sanjay, Gunman 89010-19999 2. Sh. Shyam Lal Poonia, I.A.S., (2010) 2220500 2221500-F 9996801370 [email protected] Deputy Commissioner, Sonipat 2220006 2221255 Gunman 83959-00363 3. Sh. Munish Sharma, IAS, (2014) 2222700 2220701 8368733455 [email protected] Addl. Dy. Commissioner, Sonipat 2222701,2 9650746944 Gunman, Jagbir 9728661005 Planning Officer, Joginder Lathwal 9813303608 [email protected] 4. Sh. Uday Singh, HCS 2220638 2220538 9315304377 [email protected] City Magistrate, Sonipat Rakesh, Gunman 8168916374 5. Sh .Vijay Singh, HCS 2222100 2222300 9671738833 [email protected] SDM, Sonipat Inder, Gunman 8395900365 9466821680 6. Sh. Ashish Kumar, HCS, 01263-252049 252050 9416288843 [email protected] SDM, Gohana Sanjeev, Gunman 9813759163 7. Ms. Shweta Suhag, HCS, 2584055 82850-00716 sdmkharkhoda@gmail. SDM, Kharkhoda com Ravinder, Gunman 80594-76260 8. Sh . Surender Pal, HCS, SDM, 2460810 2460800 9888885445 [email protected] Ganaur Sh. Pawan, Gunman 9518662328 Driver- 73572-04014 81688-19475 9. Ms. Saloni Sharma, IAS (UT) 78389-90155 10. Sh. Amardeep Singh, HCS, CEO Zila 2221443 9811710744 dy.ceo.zp.snp@gmail. Parishad CEO, DRDA, Sonipat com 11. Sh. Munish Sharma, IAS, (2014) 2221937 8368733455 [email protected] Secretary, RTA Sonipat 9650746944 Jagbir Singh, Asstt. Secy. RTA 9463590022 Rakesh-9467446388 Satbir Dvr-9812850796 Rajesh Malik 7700007784 Ramesh, MVI 94668-58527 12. -

Gazetteers Organisation Revenue Department Haryana Chandigarh (India) 1998

HARYANA DISTRICT GAZETTEEERS ------------------------ REPRINT OF AMBALA DISTRICT GAZETTEER, 1923-24 GAZETTEERS ORGANISATION REVENUE DEPARTMENT HARYANA CHANDIGARH (INDIA) 1998 The Gazetteer was published in 1925 during British regime. 1st Reprint: December, 1998 © GOVERNMENT OF HARYANA Price Rs. Available from: The Controller, Printing and Stationery, Haryana, Chandigarh (India). Printed By : Controller of Printing and Stationery, Government of Haryana, Chandigarh. PREFACE TO REPRINTED EDITION The District Gazetteer is a miniature encyclopaedia and a good guide. It describes all important aspects and features of the district; historical, physical, social, economic and cultural. Officials and other persons desirous of acquainting themselves with the salient features of the district would find a study of the Gazetteer rewarding. It is of immense use for research scholars. The old gazetteers of the State published in the British regime contained very valuable information, which was not wholly reproduced in the revised volume. These gazetteers have gone out of stock and are not easily available. There is a demand for these volumes by research scholars and educationists. As such, the scheme of reprinting of old gazetteers was taken on the initiative of the Hon'ble Chief Minister of Haryana. The Ambala District Gazetteer of 1923-24 was compiled and published under the authority of Punjab Govt. The author mainly based its drafting on the assessment and final reports of the Settlement Officers. The Volume is the reprinted edition of the Ambala District Gazetteer of 1923-24. This is the ninth in the series of reprinted gazetteers of Haryana. Every care has been taken in maintaining the complete originality of the old gazetteer while reprinting. -

District Survey Report for Sustainable Sand Mining Distt. Yamuna Nagar

DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT FOR SUSTAINABLE SAND MINING DISTT. YAMUNA NAGAR The Boulder, Gravel and Sand are one of the most important construction materials. These minerals are found deposited in river bed as well as adjoining areas. These aggregates of raw materials are used in the highest volume on earth after water. Therefore, it is the need of hour that mining of these aggregates should be carried out in a scientific and environment friendly manner. In an endeavour to achieve the same, District Survey Report, apropos “the Sustainable Sand Mining Guidelines” is being prepared to identify the areas of aggradations or deposition where mining can be allowed; and identification of areas of erosion and proximity to infrastructural structural and installations where mining should be prohibited and calculation of annual rate of replenishment and allowing time for replenishment after mining in that area. 1. Introduction:- Minor Mineral Deposits: 1.1 Yamunanagar district of Haryana is located in north-eastern part of Haryana State and lies between 29° 55' to 30° 31 North latitudes and 77° 00' to 77° 35' East longitudes. The total area is 1756 square kilometers, in which there are 655 villages, 10 towns, 4 tehsils and 2 sub-tehsils. Large part of the district of Yamunanagar is situated in the Shiwalik foothills. The area of Yamuna Nagar district is bounded by the state of Himachal Pradesh in the north, by the state of Uttar Pradesh in the east, in west by Ambala district and south by Karnal and Kurukshetra Districts. 1.2 The district has a sub-tropical continental monsoon climate where we find seasonal rhythm, hot summer, cool winter, unreliable rainfall and immense variation in temperature. -

Data of Sub- Station Wise Ynr Circle.Xlsx

Data of Sub Stations/ Feeder in respect of 'OP' Circle, UHBVN, Yamuna Nagar Sr. Name of Feeder Feeding S/Stn. Telephone No. of Name & Desig., of feeder in charge & line staff Address of feeder in charge and Mobile No. feeder in No. S/Stn., line staff charge & line staff 1 Sadhaura (Urban) 66 KV Sadhaura 9355220935 Sh. Surjeet Kumar JE (Feeder In Line Staff 33 KV Colny Sadhaura 9355220935 Charge) Gurcharan Kumar LM VPO- Sadhaura 9416269820 Sh. Shiv Kumar ALM VPO- Sadhaura 9416269820 2 Kalal pur ( RDS) 9813184079 Sh.Jang Pal LM Vil- Zaffarpur 9813184079 9466487821 Sh. Sat Pal LM Vill-Kanipla 9466487821 9416417126 Sh. Kehar Chand LM Vill- Habet pur 9416417126 9416546719 Sh. Rajesh Bakshi Tunde ki Taprion 9416546719 Sh. Rajesh Kumar ALM VPO_ Sadhaura 3 Malik Pur ( AP) 9813184079 Sh.Jang Pal LM Vil- Zaffarpur 9813184079 9466487821 Sh. Sat Pal LM Vill-Kanipla 9466487821 9416417126 Sh. Kehar Chand LM Vill- Habet pur 9416417126 Sh. Rajesh Kumar ALM VPO_ Sadhaura 9416546719 Sh. Rajesh Bakshi LM Tunde ki Taprion 9416546719 4 Kulchandu (AP) 9813184079 Sh.Jang Pal LM Vil- Zaffarpur 9813184079 9466487821 Sh. Sat Pal LM Vill-Kanipla 9466487821 9416417126 Sh. Kehar Chand LM Vill- Habet pur 9416417126 9416546719 Sh. Rajesh Bakshi LM Tunde ki Taprion 9416546719 Sh. Rajesh Kumar ALM VPO_ Sadhaura 5 Habet pur ( AP) 9813184079 Sh.Jang Pal LM Vil- Zaffarpur 9813184079 9466487821 Sh. Sat Pal LM Vill-Kanipla 9466487821 9416417126 Sh. Kehar Chand LM Vill- Habet pur 9416417126 9416546719 Sh. Rajesh Bakshi Tunde ki Taprion 9416546719 Sh. Rajesh Kumar ALM VPO_ Sadhaura 6 Khan pur ( RDS) 66 KV S/Stn TalaKaur Sh. -

Government of Haryana Department of Revenue & Disaster Management

Government of Haryana Department of Revenue & Disaster Management DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN Sonipat 2016-17 Prepared By HARYANA INSTITUTE OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION, Plot 76, HIPA Complex, Sector 18, Gurugram District Disaster Management Plan, Sonipat 2016-17 ii District Disaster Management Plan, Sonipat 2016-17 iii District Disaster Management Plan, Sonipat 2016-17 Contents Page No. 1 Introduction 01 1.1 General Information 01 1.2 Topography 01 1.3 Demography 01 1.4 Climate & Rainfall 02 1.5 Land Use Pattern 02 1.6 Agriculture and Cropping Pattern 02 1.7 Industries 03 1.8 Culture 03 1.9 Transport and Connectivity 03 2 Hazard Vulnerability & Capacity Analysis 05 2.1 Hazards Analysis 05 2.2 Hazards in Sonipat 05 2.2.1 Earthquake 05 2.2.2 Chemical Hazards 05 2.2.3 Fires 06 2.2.4 Accidents 06 2.2.5 Flood 07 2.2.6 Drought 07 2.2.7 Extreme Temperature 07 2.2.8 Epidemics 08 2.2.9 Other Hazards 08 2.3 Hazards Seasonality Map 09 2.4 Vulnerability Analysis 09 2.4.1 Physical Vulnerability 09 2.4.2 Structural vulnerability 10 2.4.3 Social Vulnerability 10 2.5 Capacity Analysis 12 2.6 Risk Analysis 14 3 Institutional Mechanism 16 3.1 Institutional Mechanisms at National Level 16 3.1.1 Disaster Management Act, 2005 16 3.1.2 Central Government 16 3.1.3 Cabinet Committee on Management of Natural Calamities 18 (CCMNC) and the Cabinet Committee on Security (CCS) 3.1.4 High Level Committee (HLC) 18 3.1.5 National Crisis Management Committee (NCMC) 18 3.1.6 National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) 18 3.1.7 National Executive Committee (NEC) 19 -

Exhibitions Director Archives Dept

Phone:2561412 rdi I I r 431, SECTOR 2. PANCHKULA-134 112 ; j K.L.Zakir HUA/2006-07/ Secretary Dafeci:")/.^ Subject:-1 Seminar on the "Role of Mewat in the Freedom Struggle'i. Dearlpo ! I The Haryana Urdu Akademi, in collaboration with the District Administration Mewat, proposes to organize a Seminar on the "Role of Mewat in the Freedom Struggle" in the 1st or 2^^ week of November,2006 at Nuh. It is a very important Seminar and everyone has appreciated this proposal. A special meeting was organized a couple of weeks back ,at Nuh. A list ojf the experts/Scholars/persons associated with the families of the freedom fighters was tentatively prepared in that meeting, who could be aiv requ 3Sted to present their papers in the Seminar. Your name is also in this list. therefore, request you to please intimate the title of the paper which you ^ould like to present in the Seminar. The Seminar is expected to be inaugurated by His Excellency the Governor of Haryana on the first day of the Seminar. On the Second day, papers will be presented by the scholars/experts/others and in tlie valedictory session, on the second day, a report of the Seminar will be presented along with the recommendations. I request you to see the possibility of putting up an exhibition during the Seminar at Nuh, in the Y.M.D. College, which would also be inaugurated by His Excellency on the first day and it would remain open for the students of the college ,other educational intuitions and general public, on the second day. -

Village & Townwise Primary Census Abstract

CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 SERIES -8 HARYANA DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PART XII-A&B VILLAGE, & TOWN DIRECTORY VILLAGE & TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT DIST.RICT BHIWANI Director of Census Operations Haryana Published by : The Government of Haryana, 1995 , . '. HARYANA C.D. BLOCKS DISTRICT BHIWANI A BAWAN I KHERA R Km 5 0 5 10 15 20 Km \ 5 A hAd k--------d \1 ~~ BH IWANI t-------------d Po B ." '0 ~3 C T :3 C DADRI-I R 0 DADRI - Il \ E BADHRA ... LOHARU ('l TOSHAM H 51WANI A_ RF"~"o ''''' • .)' Igorf) •• ,. RS Western Yamuna Cana L . WY. c. ·......,··L -<I C.D. BLOCK BOUNDARY EXCLUDES STATUtORY TOWN (S) BOUNDARIES ARE UPDATED UPTO 1 ,1. 1990 BOUNDARY , STAT E ... -,"p_-,,_.. _" Km 10 0 10 11m DI';,T RI CT .. L_..j__.J TAHSIL ... C. D . BLOCK ... .. ~ . _r" ~ V-..J" HEADQUARTERS : DISTRICT : TAHSIL: C D.BLOCK .. @:© : 0 \ t, TAH SIL ~ NHIO .Y'-"\ {~ .'?!';W A N I KHERA\ NATIONAL HIGHWAY .. (' ."C'........ 1 ...-'~ ....... SH20 STATE HIGHWAY ., t TAHSil '1 TAH SIL l ,~( l "1 S,WANI ~ T05HAM ·" TAH S~L j".... IMPORTANT METALLED ROAD .. '\ <' .i j BH IWAN I I '-. • r-...... ~ " (' .J' ( RAILWAY LINE WIT H STA110N, BROAD GAUGE . , \ (/ .-At"'..!' \.., METRE GAUGE · . · l )TAHSIL ".l.._../ ' . '1 1,,1"11,: '(LOHARU/ TAH SIL OAORI r "\;') CANAL .. · .. ....... .. '" . .. Pur '\ I...... .( VILLAGE HAVING 5000AND ABOVE POPULATION WITH NAME ..,." y., • " '- . ~ :"''_'';.q URBAN AREA WITH POPULATION SIZE- CLASS l.ltI.IV&V ._.; ~ , POST AND TELEGRAPH OFFICE ... .. .....PTO " [iii [I] DEGREE COLLE GE AND TECHNICAL INSTITUTION.. '" BOUNDARY . STATE REST HOuSE .TRAVELLERS BUNGALOW AND CANAL: BUNGALOW RH.TB .CB DISTRICT Other villages having PTO/RH/TB/CB elc. -

District Ambala

AGENDA FOR 6TH DIVISIONAL DEVELOPMENT REVIEW SESSION OF AMBALA DIVISION TO BE HELD ON 04.12.2009 AT 11.00 AM District Ambala Sr. Department Agenda Items DC’s Comments Departmental Comments Decision taken in Action Taken Remarks No. the 5th DDRS Report 1. Public Works Construction of H.L. DC report that- Bridge Earlier for this purpose an estimate amounting CS directed: that this Latter issued by this office Department submitted the (B&R) Bridge over Sadhaura nadi over Sadhura Nadi on to Rs.450 lacs was prepared by the PWD matter needs to be to S.E. PWD B&R for report that DDRS approval on Shahbad from Barara- Shahabad from Barara- B&R department but the amount was not examined from the submission the report for the project was not Kala Ambala to Village Kala Ambala to village sanctioned by the govt and in the meantime point of view of regarding feasibility and received but in the Sahila. Sahila is required. the temporary arrangement has been made by feasibility and availability of funds but meantime arrangement has the Panchayat Department from NAREGA availability of funds. due to non sanction of been made by the Panchayat with an expenditure of Rs.35 lacs. amount, this matter has department from AREGA been transferred to Work has been completed Panchayat Department and CC Road wok is under under NAREGA scheme. progress for which an amount of Rs.15. lacs are to be obtained from NAREGA to complete the CC Road work. 2. Public Works Construction of H.L. DC reports that- Bridge The approximate cost of this bridge will be CS directed that::- That Latter issued by this office Department submitted the (B&R). -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Of Dr. R.S. Bisht Joint Director General (Retd.) Archaeological Survey of India & Padma Shri Awardee, 2013 Address: 9/19, Sector-3, Rajendranagar, Sahibabad, Ghaziabad – 201005 (U.P.) Tel: 0120-3260196; Mob: 09990076074 Email: [email protected] i Contents Pages 1. Personal Data 1-2 2. Excavations & Research 3-4 3. Conservation of Monuments 5 4. Museum Activities 6-7 5. Teaching & Training 8 6. Research Publications 9-12 7. A Few Important Research papers presented 13-14 at Seminars and Conferences 8. Prestigious Lectures and Addresses 15-19 9. Memorial Lectures 20 10. Foreign Countries and Places Visited 21-22 11. Members on Academic and other Committees 23-24 12. Setting up of the Sarasvati Heritage Project 25 13. Awards received 26-28 ii CURRICULUM VITAE 1. Personal Data Name : DR. RAVINDRA SINGH BISHT Father's Name : Lt. Shri L. S. Bisht Date of Birth : 2nd January 1944 Nationality : Indian by birth Permanent Address : 9/19, Sector-3, Rajendranagar, Sahibabad Ghaziabad – 201 005 (U.P.) Academic Qualifications Degree Subject University/ Institution Year M.A . Ancient Indian History and Lucknow University, 1965. Culture, PGDA , Prehistory, Protohistory, School of Archaeology 1967 Historical archaeology, Conservation (Archl. Survey of India) of Monuments, Chemical cleaning & preservation, Museum methods, Antiquarian laws, Survey, Photography & Drawing Ph. D. Emerging Perspectives of Kumaun University 2002. the Harappan Civilization in the Light of Recent Excavations at Banawali and Dholavira Visharad Hindi Litt., Sanskrit, : Hindi Sahitya Sammelan, Prayag 1958 Sahityaratna, Hindi Litt. -do- 1960 1 Professional Experience 35 years’ experience in Archaeological Research, Conservation & Environmental Development of National Monuments and Administration, etc. -

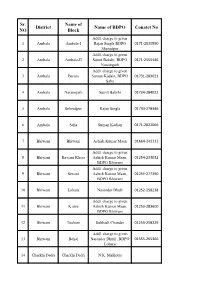

Sr. NO District Name of Block Name of BDPO Conatct No

Sr. Name of District Name of BDPO Conatct No NO Block Addl. charge to given 1 Ambala Ambala-I Rajan Singla BDPO 0171-2530550 Shazadpur Addl. charge to given 2 Ambala Ambala-II Sumit Bakshi, BDPO 0171-2555446 Naraingarh Addl. charge to given 3 Ambala Barara Suman Kadain, BDPO 01731-283021 Saha 4 Ambala Naraingarh Sumit Bakshi 01734-284022 5 Ambala Sehzadpur Rajan Singla 01734-278346 6 Ambala Saha Suman Kadian 0171-2822066 7 Bhiwani Bhiwani Ashish Kumar Maan 01664-242212 Addl. charge to given 8 Bhiwani Bawani Khera Ashish Kumar Maan, 01254-233032 BDPO Bhiwani Addl. charge to given 9 Bhiwani Siwani Ashish Kumar Maan, 01255-277390 BDPO Bhiwani 10 Bhiwani Loharu Narender Dhull 01252-258238 Addl. charge to given 11 Bhiwani K airu Ashish Kumar Maan, 01253-283600 BDPO Bhiwani 12 Bhiwani Tosham Subhash Chander 01253-258229 Addl. charge to given 13 Bhiwani Behal Narender Dhull , BDPO 01555-265366 Loharu 14 Charkhi Dadri Charkhi Dadri N.K. Malhotra Addl. charge to given 15 Charkhi Dadri Bond Narender Singh, BDPO 01252-220071 Charkhi Dadri Addl. charge to given 16 Charkhi Dadri Jhoju Ashok Kumar Chikara, 01250-220053 BDPO Badhra 17 Charkhi Dadri Badhra Jitender Kumar 01252-253295 18 Faridabad Faridabad Pardeep -I (ESM) 0129-4077237 19 Faridabad Ballabgarh Pooja Sharma 0129-2242244 Addl. charge to given 20 Faridabad Tigaon Pardeep-I, BDPO 9991188187/land line not av Faridabad Addl. charge to given 21 Faridabad Prithla Pooja Sharma, BDPO 01275-262386 Ballabgarh 22 Fatehabad Fatehabad Sombir 01667-220018 Addl. charge to given 23 Fatehabad Ratia Ravinder Kumar, BDPO 01697-250052 Bhuna 24 Fatehabad Tohana Narender Singh 01692-230064 Addl. -

CASTE SYSTEM in INDIA Iwaiter of Hibrarp & Information ^Titntt

CASTE SYSTEM IN INDIA A SELECT ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of iWaiter of Hibrarp & information ^titntt 1994-95 BY AMEENA KHATOON Roll No. 94 LSM • 09 Enroiament No. V • 6409 UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF Mr. Shabahat Husaln (Chairman) DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY & INFORMATION SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 1995 T: 2 8 K:'^ 1996 DS2675 d^ r1^ . 0-^' =^ Uo ulna J/ f —> ^^^^^^^^K CONTENTS^, • • • Acknowledgement 1 -11 • • • • Scope and Methodology III - VI Introduction 1-ls List of Subject Heading . 7i- B$' Annotated Bibliography 87 -^^^ Author Index .zm - 243 Title Index X4^-Z^t L —i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my sincere and earnest thanks to my teacher and supervisor Mr. Shabahat Husain (Chairman), who inspite of his many pre Qoccupat ions spared his precious time to guide and inspire me at each and every step, during the course of this investigation. His deep critical understanding of the problem helped me in compiling this bibliography. I am highly indebted to eminent teacher Mr. Hasan Zamarrud, Reader, Department of Library & Information Science, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh for the encourage Cment that I have always received from hijft* during the period I have ben associated with the department of Library Science. I am also highly grateful to the respect teachers of my department professor, Mohammadd Sabir Husain, Ex-Chairman, S. Mustafa Zaidi, Reader, Mr. M.A.K. Khan, Ex-Reader, Department of Library & Information Science, A.M.U., Aligarh. I also want to acknowledge Messrs. Mohd Aslam, Asif Farid, Jamal Ahmad Siddiqui, who extended their 11 full Co-operation, whenever I needed.