Class Consciousness 10 Things New Teachers Should Know (And Veteran Teachers Should Remember)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wiki-Hacking: Opening up the Academy with Wikipedia

St. John's University St. John's Scholar Faculty Publications Department of English 2010 Wiki-hacking: Opening Up the Academy with Wikipedia Adrianne Wadewitz Occidental College Anne Ellen Geller St. John's University, [email protected] Jon Beasley-Murray University of British Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.stjohns.edu/english_facpubs Part of the Education Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Wadewitz, A., Geller, A. E., & Beasley-Murray, J. (2010). Wiki-hacking: Opening Up the Academy with Wikipedia. Hacking the Academy Retrieved from https://scholar.stjohns.edu/english_facpubs/4 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at St. John's Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of St. John's Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Wiki-hacking: Opening up the academy with Wikipedia Contents Wiki-hacking: Opening up the academy with Wikipedia Introduction Wikipedia in academia Constructing knowledge Writing within discourse communities What's missing from Wikipedia Postscript: Authorship and attribution in this article Links Notes Bibliography Wiki-hacking: Opening up the academy with Wikipedia By Adrianne Wadewitz, Anne Ellen Geller, Jon Beasley-Murray Introduction A week ago, on Friday, May 21, 2010, we three were part of a roundtable dedicated to Wikipedia and pedagogy as part of the 2010 Writing Across the Curriculum (http://www.indiana.edu/~wac2010/abstracts.shtml) conference. That was our first face-to-face encounter; none of us had ever met in real life. -

The Artillery of Critique Versus the General Uncritical Consensus: Standing up to Propaganda, 1990-1999

THE ARTILLERY OF CRITIQUE VERSUS THE GENERAL UNCRITICAL CONSENSUS: STANDING UP TO PROPAGANDA, 1990-1999 by Andrew Alexander Monti Master of Arts, York University, Toronto, Canada, 2013 Bachelor of Science, Bocconi University, Milan, Italy, 2005 A dissertation presented to Ryerson University and York University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Joint Program of Communication and Culture Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2018 © Andrew Alexander Monti, 2018 AUTHOR’S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A DISSERTATION I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this dissertation. This is a true copy of the dissertation, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this dissertation to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this dissertation by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my dissertation may be made electronically available to the public. ii ABSTRACT The Artillery of Critique versus the General Uncritical Consensus: Standing Up to Propaganda, 1990-1999 Andrew Alexander Monti Doctor of Philosophy Communication and Culture Ryerson University, 2018 In 2011, leading comedy scholars singled-out two shortcomings in stand-up comedy research. The first shortcoming suggests a theoretical void: that although “a number of different disciplines take comedy as their subject matter, the opportunities afforded to the inter-disciplinary study of comedy are rarely, if ever, capitalized on.”1 The second indicates a methodological void: there is a “lack of literature on ‘how’ to analyse stand-up comedy.”2 This research project examines the relationship between political consciousness and satirical humour in stand-up comedy and attempts to redress these two shortcomings. -

The GRAMMY Museum Presents George Carlin: a Place for My Stuff

The GRAMMY Museum Presents George Carlin: A Place For My Stuff New Display to Open Sept. 30 Commemorating The Late GRAMMY-winning comedian WHO: The GRAMMY Museum will commemorate GRAMMY-winning comedian George Carlin with a new display opening Wednesday, Sept. 30, 2015 on the Museum's third floor. The exhibit will mark the third display in the Museum's comedy series, following previous tributes to Rodney Dangerfield and Joan Rivers. WHAT: Artifacts on display in George Carlin: A Place For My Stuff will include: Carlin's GRAMMY Awards and other accolades Childhood scrapbook and photos The set list from his performances on The Tonight Show in 1962 and The Ed Sullivan Show in 1971 His public arrest records Script from the 1999 cult film Dogma And more "Ever since I became the keeper of my dad's stuff in 2008, I have enjoyed sharing little bits of it with friends and comedians," said Kelly Carlin, the comedian's daughter. "But to know that his fans will now get to see some of it, makes my heart swell with joy. I am thrilled that the GRAMMY Museum is creating a place for his stuff." "George Carlin helped redefine the art form of stand-up comedy. He used his talent to not only entertain, but to question conventional wisdom and social injustices," said Bob Santelli, Executive Director of the GRAMMY Museum. "With this latest display in our comedy series, we continue to spotlight some of the greatest comedy acts, many of whom have been recognized by the GRAMMY Awards." WHEN & WHERE: George Carlin: A Place For My Stuff will be on display at the GRAMMY Museum through March 2016. -

Mercer Mayer's Little Critter Series, the Queer Art of Failure, and The

52.1 (2014) Feature Articles: The Biggest Loser: Mercer Mayer's Little Critter Series, the Queer Art of Failure, and the American Obsession with Achievement • Hey, I Still Can’t See Myself! The Difficult Positioning of Two-Spirit Identities in YA Literature • The Invisibility of Lesbian Mother Families in the South Austra- lian Premier’s Reading Challenge • What a Shame! Gay Shame in Isabelle Holland’s The Man Without a Face • Sexual Slipstreams and the Limits of Magic Realism: Why a Bisexual Cinderella May Not Be All That “Queer” • "A girl. A machine. A freak”: A Consideration of Contemporary Queer Compos- ites • A Doctor for Who(m)?: Queer Temporalities and the Sexualized Child The Journal of IBBY, the International Board on Books for Young People Copyright © 2014 by Bookbird, Inc. Reproduction of articles in Bookbird requires permission in writing from the editor. Editor: Roxanne Harde, University of Alberta—Augustana Faculty (Canada) Address for submissions and other editorial correspondence: [email protected] Bookbird’s editorial office is supported by the Augustana Faculty at the University of Alberta, Camrose, Alberta, Canada. Editorial Review Board: Peter E. Cumming, York University (Canada); Debra Dudek, University of Wollongong (Australia); Libby Gruner, University of Richmond (USA); Helene Høyrup, Royal School of Library & Information Science (Denmark); Judith Inggs, University of the Witwatersrand (South Africa); Ingrid Johnston, University of Albert, Faculty of Education (Canada); Shelley King, Queen’s University (Canada); Helen Luu, Royal Military College (Canada); Michelle Martin, University of South Carolina (USA); Beatriz Alcubierre Moya, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos (Mexico); Lissa Paul, Brock University (Canada); Laura Robinson, Royal Military College (Canada); Bjorn Sundmark, Malmö University (Sweden); Margaret Zeegers, University of Ballarat (Australia); Board of Bookbird, Inc. -

COMEDY WRITING SECRETS, Copyright 2005 © by Melvin Helitzer

secrets 2nd edition secrets the best-selling book on how to think funny, write funny, act funny, and get paid for it Mel Helitzer with Mark Shatz WRITER'S DIGEST BOOKS Cincinnati, Ohio www. writersdigest.com COMEDY WRITING SECRETS, Copyright 2005 © by Melvin Helitzer. Printed and bound in the United States of America. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote passages in a review. Published by Writer's Digest Books, an imprint of F+W Publications, Inc., 4700 East Galbraith Road, Cincinnati, Ohio 45236, (800) 289-0963. Second edition. Other fine Writer's Digest Books are available at your local bookstore or direct from the publisher. 09 08 07 06 05 5 4 3 2 1 Distributed in Canada by Fraser Direct, 100 Armstrong Avenue, Georgetown, ON, Canada L7G 5S4, Tel: (905) 877-4411. Distributed in the U.K. and Europe by David & Charles, Brunei House, Newton Abbot, Devon, TQ12 4PU, England, Tel: (+44) 1626 323200, Fax: (+44) 1626 323319, E-mail: [email protected]. Distributed in Australia by Capricorn Link, P.O. Box 704, S. Windsor NSW, 2756 Australia, Tel: (02) 4577-3555. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Helitzer, Melvin. Comedy writing secrets: the best-selling book on how to think funny, write funny, act funny, and get paid for it / by Mel Helitzer with Mark Shatz. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 1-58297-357-1 (pbk.: alk. -

Politically Correct Language in George Carlin

Montclair State University Montclair State University Digital Commons Theses, Dissertations and Culminating Projects 5-2020 Politically Correct Language in George Carlin Alan Schultz Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.montclair.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Abstract American stand-up comedian George Carlin is notable for his long-standing popularity from the early 60s up until his death in 2008. In this paper, I examine George Carlin’s stance on politically correct language. Focusing on his three books Brain Droppings, Napalm and Silly Putty, and When Will Jesus Bring the Pork Chops?, I show how his attempts to remove himself from a politically correct system ultimately fail as he adheres to his own ideals of language and morality. Using his texts and various work from Stanley Fish to support these claims, I show how Carlin ridicules the redundancies and hypocrisies that exist when groups claim words as their own. While breaking down these claims on political correctness, Carlin implements his own set of values. I show how there is no direct way to escape politicizing language. However, Carlin’s position as stand-up comic allows for a more fluid approach to politically correct language, as it offers a way to shift leanings and explore various forms of ideology permitting audiences a way to think differently about the world around them. POLITICALLY CORRECT LANGUAGE IN GEORGE CARLIN A THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts by Alan Schultz Montclair State University Montclair, NJ 2020 Table of Contents Thesis Page 1 Works Cited Page 27 Schultz 1 The 1960s and ’70s were times of massive cultural change for America. -

Disclaimer—& 71 Book Quotes

Links within “Main” & Disclaimer & 71 Book Quotes 1. The Decoration of Independence - Upload (PDF) of Catch Me If You Can QUOTE - Two Little Mice (imdb) 2. know their rights - State constitution (United States) (Wiki) 3. cop-like expression - Miranda warning (wiki) 4. challenge the industry - Hook - Don’t Mess With Me Man, I’m A Lawyer (Youtube—0:04) 5. a fairly short explanation of the industry - Big Daddy - That Guy Doesn’t Count. He Can’t Even Read (Youtube—0:03) 6. 2 - The Prestige - Teach You How To Read (Youtube—0:12) 7. how and why - Upload (PDF) of Therein lies the rub (idiom definition) 8. it’s very difficult just to organize the industry’s tactics - Upload (PDF) of In the weeds (definition—wiktionary) 9. 2 - Upload (PDF) of Tease out (idiom definition) 10. blended - Spaghetti junction (wiki) 11. 2 - Upload (PDF) of Foreshadowing (wiki) 12. 3 - Patience (wiki) 13. first few hundred lines (not sentences) or so - Stretching (wiki) 14. 2 - Warming up (wiki) 15. pictures - Mug shot (wiki) 16. not much fun involved - South Park - Cartmanland (GIF) (Giphy) (Youtube—0:12) 17. The Cat in the Hat - The Cat in the Hat (wiki) 18. more of them have a college degree than ever before - Correlation and dependence (wiki) 19. hopefully someone was injured - Tropic Thunder - We’ll weep for him…In the press (GetYarn) (Youtube—0:11) 20. 2 - Wedding Crashers - Funeral Scene (Youtube—0:42) 21. many cheat - Casino (1995) - Cheater’s Justice (Youtube—1:33) 22. house of representatives - Upload (PDF) Pic of Messy House—Kids Doing Whatever—Parent Just Sitting There & Pregnant 23. -

George Carlin 1 George Carlin

George Carlin 1 George Carlin George Carlin Carlin in Trenton, New Jersey on April 4, 2008 Birth name George Denis Patrick Carlin Born May 12, 1937Manhattan, New York, U.S. Died June 22, 2008 (aged 71)Santa Monica, California, U.S. Medium Stand-up, television, film, books, radio Nationality American Years active 1956–2008 Genres Character comedy, observational comedy, Insult comedy, wit/word play, satire/political satire, black comedy, surreal humor, sarcasm, blue comedy Subject(s) American culture, American English, everyday life, atheism, recreational drug use, death, philosophy, human behavior, American politics, parenting, children, religion, profanity, psychology, Anarchism, race relations, old age, pop culture, self-deprecation, childhood, family [1] [2] [2] [3] [4] [5] [2] [5] [2] [5] Influences Danny Kaye, Jonathan Winters, Lenny Bruce, Richard Pryor, Jerry Lewis, Marx Brothers, Mort [4] [5] [5] [2] [5] Sahl, Spike Jones, Ernie Kovacs, Ritz Brothers Monty Python [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] Influenced Chris Rock, Jerry Seinfeld, Bill Hicks, Jim Norton, Sam Kinison, Louis C.K., Bill Cosby, Lewis Black, Jon [11] [12] [13] [14] [15] [16] Stewart, Stephen Colbert, Bill Maher, Denis Leary, Patrice O'Neal, Adam Carolla, Colin Quinn, Steven [17] [18] [19] [19] [20] Wright, Russell Peters, Jay Leno, Ben Stiller, Kevin Smith Spouse Brenda Hosbrook (August 5, 1961 — May 11, 1997) (her death) 1 child [21] Sally Wade (June 24, 1998 — June 22, 2008) (his death) Notable works Class Clown and roles "Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television" Mr. Conductor -

View / Open Ada07-Wpthr-Pea-2015

2/26/2021 WP:THREATENING2MEN: Misogynist Infopolitics and the Hegemony of the Asshole Consensus on English Wikipedia - Ada New Media ISSUE NO. 7 WP:THREATENING2MEN: Misogynist Infopolitics and the Hegemony of the Asshole Consensus on English Wikipedia Bryce Peake When schools discourage reporting, they collude with many societal forces to cover up sexual violence. Sexual violence thrives on secrecy. – Jennifer Freyd, ’Official Campus Statistics for Sexual Violence Mislead’ (http://america.aljazeera.com/opinions/2014/7/college-campus- sexualassaultsafetydatawhitehousegender.html) Spring 2014 was a long season, marked by a campus-wide anti-rape movement that took off at the University of Oregon (UO). In the wake of a high profile case, administrators callously and robotically rehearsed the “one time is too many” catch phrase that, through its rhetorical singularity, renders campus sexual violence an “isolated issue.” Arguments that UO was somehow unique or unusual in its unsafe environment and unethical public relations approach to public safety became rampant in public forums and the comment sections of online articles. The idea of writing campus sexual violence into Wikipedia was born of these circumstances, growing out of a conversation with campus activists about universities’ efforts to keep campus sexual violence invisible. By increasing the amount of freely available information on the long history of campus sexual violence across the United States, we could provide information for people looking to learn about the ways Oregon was -

Wikipedia's Gender Gap, and What Would Hari Seldon Do About It.Pdf

Wikipedia’s gender gap, and what would Hari Seldon do about it? Dame Rosie Stephenson-Goodknight OCLC Distinguished Seminar Series ORCID: 0000-0001-5760-0881 Columbus, Ohio, US Wikidata: Q24896970 #OCLCdss @Rosiestep | @wikimediadc 14 November 2018 | CC-BY-SA 4.0 Introduction 2 3 4 “Imagine a world in which every single person on the planet is given free access to the sum of all human knowledge. That's what we're doing.” -Jimmy Wales 5 6 7 8 9 Wikimedia 10 11 Encyclopedia Galactica 12 WWHSD? (What would Hari Seldon do?) 13 Diccionario biográfico, geograf́ico e histórico de Venezuela, Ramón Armando Rodriguez (1957) Women’s biographies 3.6% 14 Wikipedia’s gender bias 15 Participatory gender bias 16 2010 women editors 12.6% 2011 women editors 8.5% 17 2011 Wikimedia Strategic Plan 18 2011 Sue Gardner, Executive Director, Wikimedia 19 2012 Conflict, confidence, or criticism: An empirical examination of the gender gap in wikipedia -Collier & Bear 20 2013 Wikipedia's gender gap and the complicated reality of systemic gender -Adrianne Wadewitz 21 Assumption #1 It is the responsibility of women to fix sexism on Wikipedia. Wadewitz, Adrianne (26 July 2013). “Wikipedia's gender gap and the complicated reality of systemic gender bias Page” Hastac. 22 Assumption #2 Women do not further patriarchal knowledge and power structures. 23 Assumption #3 Women will edit underrepresented topics. 24 Assumption #4 Women will make Wikipedia a nicer place. 25 Assumption #5 Women have free time to dedicate to Wikipedia. 26 2018, women editors = 9% 27 Representation gender bias 28 2018, women’s biographies = 17.67% 29 Associativity of words with gender 30 31 32 #1 Differences in meta-data are coherent with results in previous work, where women biographies were found to contain more marriage-related events than men’s. -

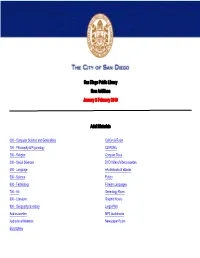

San Diego Public Library New Additions January & February 2010

San Diego Public Library New Additions January & February 2010 Adult Materials 000 - Computer Science and Generalities California Room 100 - Philosophy & Psychology CD-ROMs 200 - Religion Compact Discs 300 - Social Sciences DVD Videos/Videocassettes 400 - Language eAudiobooks & eBooks 500 - Science Fiction 600 - Technology Foreign Languages 700 - Art Genealogy Room 800 - Literature Graphic Novels 900 - Geography & History Large Print Audiocassettes MP3 Audiobooks Audiovisual Materials Newspaper Room Biographies Fiction Call # Author Title FIC/ABEL Abel, Kenneth. Down in the flood FIC/ABERCROMBIE Abercrombie, Joe. Best served cold [SCI-FI] FIC/ABRAHAM Abraham, Daniel. The price of spring FIC/ACKROYD Ackroyd, Peter The casebook of Victor Frankenstein [MYST] FIC/ADAMS Adams, Jane The power of one FIC/ADIGA Adiga, Aravind. The white tiger FIC/AHERN Ahern, Cecelia The gift [MYST] FIC/ALBERT Albert, Susan Wittig. Spanish dagger FIC/ALBOM Albom, Mitch For one more day FIC/ALBOM Albom, Mitch The five people you meet in heaven [MYST] FIC/ALEXANDER Alexander, Tasha A poisoned season FIC/ALLENDE Allende, Isabel. Daughter of fortune FIC/ALLENDE Allende, Isabel. Inés of my soul FIC/ALVAREZ Alvarez, Julia. In the time of the butterflies FIC/AMMANITI Ammaniti, Niccolò As God commands FIC/ANTHONY Anthony, Jessica The convalescent FIC/ANTON Anton, Maggie. Rashi's daughters. Book III, Rachel [MYST] FIC/APODACA Apodaca, Jennifer. Dying to meet you FIC/ARMSTRONG Armstrong, Kelley. Living with the dead FIC/ARSENAULT Arsenault, Emily. The broken teaglass FIC/ARSENAULT Arsenault, Mark. Loot the moon FIC/ATKINSON Atkinson, Kate. Case histories FIC/ATWOOD Atwood, Margaret Bodily harm FIC/ATWOOD Atwood, Margaret The blind assassin FIC/ATWOOD Atwood, Margaret The year of the flood FIC/AUEL Auel, Jean M. -

Wikipedia @ 20

Wikipedia @ 20 Wikipedia @ 20 Stories of an Incomplete Revolution Edited by Joseph Reagle and Jackie Koerner The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England © 2020 Massachusetts Institute of Technology This work is subject to a Creative Commons CC BY- NC 4.0 license. Subject to such license, all rights are reserved. The open access edition of this book was made possible by generous funding from Knowledge Unlatched, Northeastern University Communication Studies Department, and Wikimedia Foundation. This book was set in Stone Serif and Stone Sans by Westchester Publishing Ser vices. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Reagle, Joseph, editor. | Koerner, Jackie, editor. Title: Wikipedia @ 20 : stories of an incomplete revolution / edited by Joseph M. Reagle and Jackie Koerner. Other titles: Wikipedia at 20 Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : The MIT Press, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2020000804 | ISBN 9780262538176 (paperback) Subjects: LCSH: Wikipedia--History. Classification: LCC AE100 .W54 2020 | DDC 030--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020000804 Contents Preface ix Introduction: Connections 1 Joseph Reagle and Jackie Koerner I Hindsight 1 The Many (Reported) Deaths of Wikipedia 9 Joseph Reagle 2 From Anarchy to Wikiality, Glaring Bias to Good Cop: Press Coverage of Wikipedia’s First Two Decades 21 Omer Benjakob and Stephen Harrison 3 From Utopia to Practice and Back 43 Yochai Benkler 4 An Encyclopedia with Breaking News 55 Brian Keegan 5 Paid with Interest: COI Editing and Its Discontents 71 William Beutler II Connection 6 Wikipedia and Libraries 89 Phoebe Ayers 7 Three Links: Be Bold, Assume Good Faith, and There Are No Firm Rules 107 Rebecca Thorndike- Breeze, Cecelia A.