FACTFILE: GCSE DRAMA Components 1 & 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FY19 Annual Report View Report

Annual Report 2018–19 3 Introduction 5 Metropolitan Opera Board of Directors 6 Season Repertory and Events 14 Artist Roster 16 The Financial Results 20 Our Patrons On the cover: Yannick Nézet-Séguin takes a bow after his first official performance as Jeanette Lerman-Neubauer Music Director PHOTO: JONATHAN TICHLER / MET OPERA 2 Introduction The 2018–19 season was a historic one for the Metropolitan Opera. Not only did the company present more than 200 exiting performances, but we also welcomed Yannick Nézet-Séguin as the Met’s new Jeanette Lerman- Neubauer Music Director. Maestro Nézet-Séguin is only the third conductor to hold the title of Music Director since the company’s founding in 1883. I am also happy to report that the 2018–19 season marked the fifth year running in which the company’s finances were balanced or very nearly so, as we recorded a very small deficit of less than 1% of expenses. The season opened with the premiere of a new staging of Saint-Saëns’s epic Samson et Dalila and also included three other new productions, as well as three exhilarating full cycles of Wagner’s Ring and a full slate of 18 revivals. The Live in HD series of cinema transmissions brought opera to audiences around the world for the 13th season, with ten broadcasts reaching more than two million people. Combined earned revenue for the Met (box office, media, and presentations) totaled $121 million. As in past seasons, total paid attendance for the season in the opera house was 75%. The new productions in the 2018–19 season were the work of three distinguished directors, two having had previous successes at the Met and one making his company debut. -

Asides Magazine for SALOMÉ

2015|2016 SEASON Issue 1 TABLE OF Dear Friend, CONTENTS A few years ago in New York, I had an unforgettable theatrical experience. It was Mies Julie, ® 1 Title page Yäel Farber’s adaptation of Recipient of the 2012 Regional Theatre Tony Award 3 Cast Strindberg’s play, transferring Artistic Director Michael Kahn from its acclaimed run at the Executive Director Chris Jennings 5 About STC Edinburgh Fringe Festival. Setting the text in post- Apartheid South Africa, Yaël managed to miraculously 5 About ACA re-create the visceral shock of the original play while daringly mapping its exploration of gender and social 6 The Stories Not Told class inequalities onto an unmistakably contemporary by Drew Lichtenberg landscape. I was captivated and excited. Most importantly, I admired Yaël’s ability to transform 10 Director’s Word classical texts to speak to some of the most pressing issues of our time. I was not surprised to see Yaël by Yaël Farber quickly become one of the most sought-after directors 14 Salomé as History in international theatre. Her recent production of The adapted and directed by Yaël Farber Crucible at the Old Vic in London was nominated for and Fetish an Olivier Award, the highest honor in British theatre, by Gail P. Streete and her documentary piece, Nirbhaya, on the subject of a brutal sexual assault in India, has toured the world to Performances begin October 6, 2015 20 Creating Salomé critical acclaim. Opening Night October 13, 2015 21 Cast Biographies We presented Mies Julie to Washington audiences in our Lansburgh Theatre 2013–2014 season, where it was nominated for a Helen 27 Play in Process Hayes Award for Outstanding Visiting Production. -

Broadway Revealed: Behind the Theater Curtain

Broadway Revealed: Behind the Theater Curtain Donald Holder Lighting Designer on the set of Spider‐Man: Turn Off the Dark, Foxwoods Theater, New York, NY, 24” H x 72” W Exhibition Specifications Title: Broadway Revealed: Behind the Theater Curtain Artist: Photographer Stephen Joseph Curator: Carrie Lederer, Curator of Exhibitions and Programs Organizing Institution: Bedford Gallery, Lesher Center for the Arts, 1601 Civic Drive, Walnut Creek, CA 94596 www.bedfordgallery.org Description: The Bedford Gallery is offering an exclusive touring exhibition Broadway Revealed: Behind the Theater Curtain. This extraordinary show brings to life the mystery, glitz and over‐the‐top grandeur of New York’s most impressive Broadway theater shows. For the last three years, Bay Area photographer Stephen Joseph has captured images of the “giants” of New York theater—directors, set designers, costumers, tailors, and milliners that transform Broadway nightly. The exhibition includes many behind‐the‐scenes shots of these production artists at work in their studios, as well as stage imagery from many well‐known Broadway productions such as American Idiot, Hair, Spiderman, and several other shows. Artworks: Eighty eight (88) 360 degree panoramic photographs custom printed by the artist. The photographs are printed in a variety of sizes ranging from 10 x 30” W to 24 x 72” W. Artifacts and Ephemera: Bedford Gallery will supply an open list of the appropriate Broadway contacts to procure props, costumes and other artifacts to supplement the exhibition. Space Requirements: 2,000 – 4,500 Square Feet or 250 – 400 Linear Feet This show is elastic; a small selection of the photographs are available in varying sizes to allow each venue design an exhibition that gracefully fills the exhibition space. -

Season Premiere of Tosca Glitters

2019–20 Season Repertory and Casting Casting as of November 12, 2019 *Met debut The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess By George Gershwin, DuBose and Dorothy Heyward, and Ira Gershwin New Production Sep 23, 27, 30, Oct 5mat, 10, 13mat, 16, Jan 8, 11, 15, 18, 24, 28, Feb 1mat Conductor: David Robertson Bess: Angel Blue/Elizabeth Llewellyn* Clara: Golda Schultz/Janai Brugger Serena: Latonia Moore Maria: Denyce Graves Sportin’ Life: Frederick Ballentine* Porgy: Eric Owens/Kevin Short Crown: Alfred Walker Jake: Ryan Speedo Green/Donovan Singletary Production: James Robinson* Set Designer: Michael Yeargan Costume Designer: Catherine Zuber Lighting Designer: Donald Holder Projection Designer: Luke Halls The worldwide copyrights in the works of George Gershwin and Ira Gershwin for this presentation are licensed by the Gershwin family. GERSHWIN is a registered trademark of Gershwin Enterprises. Porgy and Bess is a registered trademark of Porgy and Bess Enterprises. A co-production of the Metropolitan Opera; Dutch National Opera, Amsterdam; and English National Opera Production a gift of The Sybil B. Harrington Endowment Fund Additional funding from Douglas Dockery Thomas Manon Jules Massenet Sep 24, 28mat, Oct 2, 5, 19, 22, 26mat ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ PRESS DEPARTMENT The Metropolitan Opera Press: 212.870.7457 [email protected] 30 Lincoln Center Plaza General: 212.799.3100 metopera.org New York, NY 10023 Fax: 212.870.7606 Conductor: Maurizio Benini Manon: Lisette Oropesa Chevalier des Grieux: Michael Fabiano Guillot de Morfontaine: Carlo Bosi Lescaut: Artur Ruciński de Brétigny: Brett Polegato* Comte des Grieux: Kwangchul Youn Production: Laurent Pelly Set Designer: Chantal Thomas Costume Designer: Laurent Pelly Lighting Designer: Joël Adam Choreographer: Lionel Hoche Associate Director: Christian Räth A co-production of the Metropolitan Opera; Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Teatro alla Scala, Milan; and Théâtre du Capitole de Toulouse Production a gift of The Sybil B. -

67Th Annual Tony Awards

The American Theatre Wing's The 2013 Tony Awards® Sunday, June 9th at 8/7c on CBS 67TH ANNUAL TONY AWARDS Best Play Best Performance by an Actress in a Leading Role in a Musical Best Costume Design of a Musical The! Assembled Parties (Richard Greenberg) Stephanie! J. Block, The Mystery of Edwin Drood Gregg! Barnes, Kinky Boots Lucky Guy (Nora Ephron) Carolee Carmello, Scandalous Rob Howell, Matilda The Musical The Testament of Mary (Colm Toíbín) Valisia LeKae, Motown The Musical Dominique Lemieux, Pippin Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike (Christopher Durang) Patina Miller, Pippin William Ivey Long, Rodgers + Hammerstein’s Cinderella Laura Osnes, Rodgers + Hammerstein’s Cinderella Best Musical Bring! It On: The Musical Best Performance by an Actor in a Featured Role in a Play Best Lighting Design of a Play A Christmas Story, The Musical Danny! Burstein, Golden Boy Jules! Fisher & Peggy Eisenhauer, Lucky Guy Kinky Boots Richard Kind, The Big Knife Donald Holder, Golden Boy Matilda The Musical Billy Magnussen, Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike Jennifer Tipton, The Testament of Mary Tony Shalhoub, Golden Boy Japhy Weideman, The Nance Best Book of a Musical Courtney B. Vance, Lucky Guy A! Christmas Story, The Musical (Joseph Robinette) Best Lighting Design of a Musical Kinky Boots (Harvey Fierstein) Best Performance by an Actress in a Featured Role in a Play Kenneth! Posner, Kinky Boots Matilda The Musical (Dennis Kelly) Carrie! Coon, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Kenneth Posner, Pippin Rodgers + Hammerstein’s Cinderella (Douglas Carter -

Tony Award Winners

M N 2015 TONY AWARD WINNERS BEST PLAY Disgraced by Ayad Akhtar Hand to God by Robert Askins The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time by Simon Stephens Wolf Hall Parts One & Two by Hilary Mantel and Mike Poulton BEST MUSICAL An American in Paris Fun Home Something Rotten! The Visit BEST REVIVAL OF A PLAY Skylight The Elephant Man This is Our Youth You Can’t Take it With You BEST REVIVAL OF A MUSICAL On the Town On the Twentieth Century The King and I GreatWhiteWay.com (212) 757-9117 (888) 517-0112 M N 2015 TONY AWARD WINNERS BEST LEADING ACTOR IN A PLAY Steven Boyer, Hand to God Bradley Cooper, The Elephant Man Ben Miles, Wolf hall Parts One & Two Bill Nighy, Skylight Alex Sharp, The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time BEST LEADING ACTRESS IN A PLAY Geneva Call, Hand to God Helen Mirren, The Audience Elisabeth Moss, The Heigi Chronicles Carey Mulligan, Skylight Ruth Wilson, Constellations BEST PERFORMANCE BY AN ACTOR IN A MUSICAL Michael Cerveris, Fun Home Robert Fairchild, An American in Paris Brian d’Arcy James, Something Rotten! Ken Watanabe, The King and I Tony Yazbeck, On The Town BEST PERFORMANCE BY AN ACTRESS IN A MUSICAL Kristin Chenowith, On the Twentieth Century Leanne Cope, An American in Paris Beth Malone, Fun Home Kelli O’Hara, The King and I Chita Rivera, The Visit GreatWhiteWay.com (212) 757-9117 | (888) 517-0112 M N 2015 TONY AWARD WINNERS BEST ORIGINAL SCORE (MUSIC / LYRICS) FOR THE THEATRE Music: Jeanine Tesori, Lyrics: Lisa Kron, Fun Home Music and Lyrics: Sting, The Last Ship Music and Lyrics: Wayne and Karey Kirkpatrick, Something Rotten! Music: John Kander, Lyrics: Fred Ebb, The Visit BEST BOOK OF A MUSICAL Craig Lucas, An American in Paris Lisa Kron, Fun Home Karey Kirkpatrick, John O’Farrell, Something Rotten! Terrence McNally, The Visit BEST PERFORMANCE BY AN ACTOR IN A FEATURED ROLE IN A PLAY Matthew Beard, Skylight K. -

Marcia Milgrom Dodge

MARCIA MILGROM DODGE Agent Evan Morse The Gersh Agency 41 Madison Avenue, 33rd Floor, New York, NY 10010 212.634.8169 [email protected] Career Overview § Freelance director & choreographer of classic and contemporary plays and musicals on Broadway, Off- Broadway, Regional, Summer Stock and University venues in the United States and abroad. More than 200 productions as director and/or choreographer § Tony Award nomination in 2010 for Best Director of a Musical, RAGTIME Revival § Published and produced playwright § First woman hired by The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts to direct and choreograph a major musical in 2009 (Ragtime) § Creative Consultant for Ringling Brothers & Barnum & Bailey Circus Fully Charged § Member of SDC since 1979; seventeen (17) years of Executive Board service § Resident Director, Born For Broadway, Annual Charity Cabaret, Founder/Producer: Sarah Galli, since 2009 § Associate Artist, Bay Street Theatre, Sag Harbor, NY, since 2008 § Associate Member of the Dramatists Guild, 2001-present § Resident Director, Phoenix Theatre Company at SUNY Purchase, 1993-1995 § Member of Actors Equity Association, 1979-1988 Selected Plays & Musicals (complete resume upon request) I approach revivals as if they are new works and I bring extensive knowledge of classical form and structure to my collaborations with new writers. I work in large venues from 11,000-seat outdoor theatres (Muny) to tiny venues such as 60-seat black box theatres (Workshop Theatre). Major Revivals RAGTIME, Broadway/Neil Simon Theatre & John F. Kennedy Center/Eisenhower Theatre MERRILY WE ROLL ALONG w/ Sondheim & Furth, Arena Stage Reimagined Classics CAT ON A HOT TIN ROOF Drury Lane Theatre FIDDLER ON THE ROOF & THE KING & I Maltz Jupiter Theatre ANGEL STREET & CRIMES OF THE HEART Cape Playhouse MEET ME IN ST. -

Diplomka Vendy-2

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI Pedagogická fakulta UP Olomouc Katedra hudební výchovy Bc. VENDULA PUMPRLOVÁ II.ro čník prezen čního navazujícího magisterského studia Obor: U čitelství anglického jazyka pro 2. stupe ň základních škol – Učitelství hudební výchovy pro 2. stupe ň základních škol a pro st řední školy ROCKOVÝ MUZIKÁL Diplomová práce Vedoucí práce: PaedDr. Jaroslav Vraštil, Ph.D. OLOMOUC 2014 Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto práci vypracovala samostatn ě a uvedla v ní veškerou literaturu a ostatní zdroje, které jsem použila. V Olomouci 15.4.2014 Pod ěkování: Děkuji PaedDr. Jaroslavu Vraštilovi, PhD. za odborné vedení diplomové práce. OBSAH ÚVOD………………………………………………………….….7 1. VÝVOJ ROCKOVÉHO MUZIKÁLU……………………......8 2. HAIR- první rockový muzikál………………………………….11 3. TOMMY………………………………………………………..22 4. STEPHEN SCHWARTZ A JEHO TVORBA……………….…26 4.1 Godspell…………………………………………………….26 4.2 Pippin……………………………………………………....29 5. JESUS CHRIST SUPERSTAR………………………………...32 6. EVITA……………………………………………………….….41 7. THE ROCKY HORROR SHOW……………………………....48 8. RENT…………………………………………………………...54 9. SPRING AWAKENING……………………………………….63 10. NEJNOV ĚJŠÍ ROCKOVÉ MUZIKÁLY…………………….67 10.1 American Idiot……………………………………………67 10.2 Next to Normal…………………………………………...68 10.3 Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark…………………………..69 11.MUZIKÁLY OVLIVN ĚNÉ ROCKEM…………………….....71 11.1 Aida……………………………………………………….71 11.2 Grease………………………………………………….....74 11.3 Little Shop of Horrors………………………………….....78 11.4 Hairspray………………………………………………….82 12. HUDEBNÍ FILMY S PÍSN ĚMI ROCKOVÝCH SKUPIN…...85 12.1 Across the Universe…………………………………….....85 12.2 The Doors……………………………………………….....86 12.3 A Hard Day´s Night…………………………………….87 12.4 Help!................................................................................88 ZÁV ĚR………………………………………………………89 LITERATURA A ZDROJE………………………………....90 Úvod Rockový muzikál je v oblasti sou časného muzikálového divadla velice populárním trendem. Díla napsaná v tomto hudebním stylu výrazně ovlivnily vývoj a sm ěř ování jak muzikálu, tak činohry v dob ě svého vzniku. -

FY17 Annual Report View Report

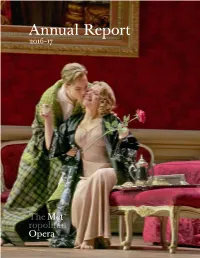

Annual Report 2016–17 1 2 4 Introduction 6 Metropolitan Opera Board of Directors 7 Season Repertory and Events 14 Artist Roster 16 The Financial Results 48 Our Patrons 3 Introduction In the 2016–17 season, the Metropolitan Opera continued to present outstanding grand opera, featuring the world’s finest artists, while maintaining balanced financial results—the third year running in which the company’s finances were balanced or very nearly so. The season opened with the premiere of a new production of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde and also included five other new stagings, as well as 20 revivals. The Live in HD series of cinema transmissions brought opera to audiences around the world for the 11th year, with ten broadcasts reaching approximately 2.3 million people. Combined earned revenue for the Met (Live in HD and box office) totaled $111 million. Total paid attendance for the season in the opera house was 75%. All six new productions in the 2016–17 season were the work of distinguished directors who had previous success at the Met. The compelling Opening Night new production of Tristan und Isolde was directed by Mariusz Treliński, who made his Met debut in 2015 with the double bill of Tchaikovsky’s Iolanta and Bartók’s Bluebeard’s Castle. French-Lebanese director Pierre Audi brought his distinctive vision to Rossini’s final operatic masterpiece Guillaume Tell, following his earlier staging of Verdi’s Attila in 2010. Robert Carsen, who first worked at the Met in 1997 on his popular production of Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin, directed a riveting new Der Rosenkavalier, the company’s first new staging of Strauss’s grand comedy since 1969. -

02-15-2020 Porgy Eve.Indd

THE GERSHWINS’ porgy and bess By George Gershwin, DuBose and Dorothy Heyward, and Ira Gershwin conductor Opera in two acts David Robertson Saturday, February 15, 2020 production 8:00–11:20 PM James Robinson set designer New Production Michael Yeargan Last time this season costume designer Catherine Zuber lighting designer The production of The Gershwins’ Porgy and Donald Holder Bess was made possible by a generous gift from projection designer Luke Halls The Sybil B. Harrington Endowment Fund and Douglas Dockery Thomas choreographer Camille A. Brown fight director David Leong general manager Peter Gelb Co-production of the Metropolitan Opera; jeanette lerman-neubauer Dutch National Opera, Amsterdam; and music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin English National Opera 2019–20 SEASON The 71st Metropolitan Opera performance of THE GERSHWINS’ porgy and bess conductor David Robertson in order of vocal appearance cl ar a a detective Janai Brugger Grant Neale mingo lily Errin Duane Brooks Tichina Vaughn* sportin’ life a policeman Chauncey Packer Bobby Mittelstadt jake an undertaker Donovan Singletary* Whitaker Mills serena annie Karen Slack Chanáe Curtis robbins “l aw yer” fr a zier Christian Mark Gibbs Arthur Woodley jim nel son Norman Garrett Jonathan Tuzo peter str awberry woman Jamez McCorkle Aundi Marie Moore maria cr ab man Denyce Graves Christian Mark Gibbs porgy a coroner Eric Owens Michael Lewis crown scipio Alfred Walker* Neo Randall bess Angel Blue Saturday, February 15, 2020, 8:00–11:20PM The worldwide copyrights in the works of George Gershwin and Ira Gershwin for this presentation are licensed by the Gershwin family. GERSHWIN is a registered trademark of Gershwin Enterprises. -

Ahmanson Theatre 2015/16 Season

AHMANSON THEATRE 2015/16 SEASON first season production The Sound of Music music by Richard Rodgers lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II book by Howard Lindsay & Russel Crouse suggested by The Trapp Family Singers by Maria Augusta Trapp choreographed by Danny Mefford directed by Jack O’Brien SEP 20 – OCT 31, 2015 second season production The Bridges of Madison County The Broadway Musical based on the novel by Robert James Waller book by Marsha Norman music and lyrics by Jason Robert Brown directed by Bartlett Sher DEC 8, 2015 – JAN 17, 2016 third season production Sean Hayes in An Act of God by David Javerbaum directed by Joe Mantello JAN 30 – MAR 13, 2016 fourth season production A Gentleman’s Guide to Love & Murder book and lyrics by Robert L. Freedman music and lyrics by Steven Lutvak choreographed by Peggy Hickey directed by Darko Tresnjak MAR 22 – MAY 1, 2016 fifth season production Rachel York and Betty Buckley in Grey Gardens book by Doug Wright murphy. photo by matthew music by Scott Frankel lyrics by Michael Korie directed by Michael Wilson JUL 2 – AUG 14, 2016 season sponsor and Andrew Samonsky (Robert). Elizabeth Stanley (Francesca) PERFORMANCES MAGAZINE P1 INSPIRING OUR FUTURE $1 million and above The Ahmanson Foundation Brindell Roberts Gottlieb $250,000 and above Center Theatre Group Affiliates Kirk & Anne Douglas The James Irvine Foundation The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Special Thanks to Center Laura & James Rosenwald & Orinoco Foundation Theatre Group’s Most Generous Annual Patrons $150,000 and above Center Theatre Group wishes to Anonymous (2) thank the following donors for their Bank of America significant gifts and for their belief in The Blue Ribbon the transformative power of theatre. -

Hamilton | December 31, 2019 – January 19, 2020 | Andrew Jackson Hall

present Hamilton | December 31, 2019 – January 19, 2020 | Andrew Jackson Hall WHAT’S NEXT? – TPAC.ORG • 615-782-4040 Drum TAO 2020 Mandy Patinkin My Fair Lady Blue Man Group Alvin Ailey JAN 28 JAN 29 FEB 4-9 FEB 11-16 FEB 28-29 Vanderbilt Orthopaedics Announcing So much more than bones and joints LINDA MILLER Run at the speed of light—or just until you can see the light at the end of the tunnel. Whatever your goal, Vanderbilt Orthopaedics is here to help you achieve it without pain. Providing comprehensive care for your orthopaedic needs, REAL ESTATE our nationally recognized Vanderbilt experts offer a full range of services from WHO’S WHO IN LUXURY REAL ESTATE sports medicine to joint replacement to pediatric orthopaedics and more. LINDALINDALINDA MILLER,MILLER, MILLER, THETHE SMILESMILE OF OFOF 30A, 30A,30A, To learn more, call (615) 913-5716 or visit VanderbiltOrthopaedics.com. HASHAS MOVED MOVED TO TO THETHE HEARTHEART OFOF 30A!30A! HAS MOVED TO THE HEART OF 30A! Franklin Mt. Juliet Spring Hill 206 Bedford Way 5002 Crossings Circle, Suite 230 1003 Reserve Blvd., Suite 130 Franklin, TN 37064 Mt. Juliet, TN 37122 Spring Hill, TN 37174 Gallatin Nashville CallCall5417 Me! Me!East County •• 850-974-8885850-974-8885 Highway 30A 300 Steam Plant Road, Suite 420 Medical Center East, South Tower Call54175417 Me!EastEast CountyCounty • 850-974-8885 HighwayHighway 30A30A Gallatin, TN 37066 1215 21st Ave. S., Suite 4200 Seagrove Beach, FL Nashville, TN 37232 SeagroveSeagrove Beach,Beach, FLFL Vanderbilt Orthopaedics is the exclusive healthcare provider for: As a teenager, Ming fought valiantly to escape one of history's darkest eras - China's Cultural Revolution - during which millions of innocent youth were deported to remote areas to face a life sentence of poverty and hard labor.