Truth and Autobiography in Stand-Up Comedy and the Genius of Doug Stanhope

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sara Pascoe to Host Special Comic Relief Live Stand-Up Show at Edinburgh Fringe

SARA PASCOE TO HOST SPECIAL COMIC RELIEF LIVE STAND-UP SHOW AT EDINBURGH FRINGE 18th July 2018: Writer, comedian and actress Sara Pascoe is set to host a special Comic Relief Live show at the Edinburgh Fringe next month. Sara, who sold out her entire run at last year’s Edinburgh Festival with her critically feted show, LadsLadsLads, will be joined by some of the UK’s most exciting comedy talent for an exclusive, one night only, stand up gig for Comic Relief. A variety of comedians will support Sara including Jamali Maddix (Vice series Hate Thy Neighbour, Chortle Student Comedian of the Year), Larry Dean (Live at the Apollo, Roast Battle), Rachel Parris (Murder in Successville, The Mash Report), Catherine Bohart (BBC New Talent Hotlist 2017) and Steen Raskopoulos (Top Coppers, Barry Award nominee). Comic Relief is also proud to present special guest Nina Conti (8 out of 10 Cats Does Countdown, Live at the Apollo, Russell Howard’s Good News) who will make an appearance on the night. Sara expressed her excitement about the show saying: “I’m super excited to be heading to the Edinburgh Fringe for this year’s Comic Relief stand-up show. The city is always buzzing and it’s a brilliant place to discover the hottest comedy talent. I’ll be sharing the stage with some of the best comedians on the circuit so it’s a great chance for the audience to enjoy them all in one place. It’s even better knowing that it’s for a great cause - money raised from the gig will enable Comic Relief to improve people’s lives here in the UK and around the world. -

Wells Comedy Festival 2016: Full Line-Up Announced for Somerset's Stand-Up Shindig

Wells Comedy Festival 2016: full line-up announced for Somerset’s stand-up shindig More names added to this year’s Wells Comedy Festival, including Mark Steel, Katy Brand, Dane Baptiste and Ed Gamble The Wells Comedy Festival – which takes place 3-5 June 2016 – has revealed its full line-up, with a whole host of new acts joining the previously announced Stewart Lee, Sara Pascoe, Arthur Smith, Robert Newman, Sam Simmons, Bridget Christie and many others. More than 20 comedians are making the trip to England’s smallest city to play the ‘weekend-long stand-up jamboree’ (The Guardian). New additions include award-winning Radio 4 star Mark Steel, TV regular Katy Brand (of ‘Big Ass Show’ fame), Foster’s Best Newcomer nominee Dane Baptiste and ‘Almost Royal’ and ‘Mock the Week’ star Ed Gamble. Plus silly stand-ups Lou Sanders and Stuart Laws and ‘QI’ elf, ‘No Such Thing as a Fish’ podcaster and Private Eye writer Andrew Hunter Murray. Comics already announced include a very special guest who can’t be named here, Bafta-winning BBC star Stewart Lee (who has now added a second show), panel show regular Sara Pascoe, legendary grump Arthur Smith, ‘Infinite Monkey Cage’ co-host Robin Ince and Foster’s Edinburgh Comedy Award-winners Bridget Christie and Sam Simmons. Plus Robert Newman, Tony Law, Spencer Jones as the Herbert, Pat Cahill and the Comedians Cinema Club performing the Wells-shot cop comedy movie ‘Hot Fuzz’, live. Ben Williams, Wells Comedy Festival Founder and Producer said, ‘I’m over the moon with the line-up for this year’s fest, and so pleased to have household name comics performing alongside some of my personal favourites, like Lou Sanders and Stuart Laws. -

Festival Program Canberracomedyfestival.Com.Au

Over 50 Hilarious Shows! Festival Program canberracomedyfestival.com.au canberracomedyfestival canberracomedy canberracomedy #CBRcomedy Canberra Comedy Festival app ► available for iPhone & Android DINE LAUGH STAY FIRST EDITION BAR & DINING CANBERRA COMEDY FESTIVAL NOVOTEL CANBERRA Accommodation from $180* per room, per night Start the night off right with a 3 cheese platter & 2 house drinks for only $35* firsteditioncanberra.com.au 02 6245 5000 | 65 Northbourne Avenue, Canberra novotelcanberra.com.au *Valid 19 - 25 March 2018. House drinks include house beer, house red and white wine only. Accommodation subject to availability. T&C’s apply. WELCOME FROM THE CHIEF MINISTER I am delighted to welcome you to the Canberra Comedy Festival 2018. The Festival is now highly anticipated every March by thousands of Canberrans as our city transforms into a thriving comedy hub. The ACT Government is proud to support the growth of the Festival year-on- year, and I’m pleased to see that 2018 is the biggest program ever. In particular, in 2018, that growth includes the Festival Square bar and entertainment area in Civic Square. The Festival has proven Canberra audiences are on the cutting edge of arts participation. Shows at the Festival in 2017 went on to be nominated for prestigious awards around the country, and one (Hannah Gadsby) even picked up an impressive award at the 2017 Edinburgh Fringe Festival. I’ve got tickets for a few big nights at the Festival, and I hope to see you there. Andrew Barr MLA ACT Chief Minister CANBERRA COMEDY FESTIVAL GALA Tue 20 March 7pm (120min) $89 / $79 * Canberra Theatre, Canberra Theatre Centre SOLD OUT. -

Polysèmes, 23 | 2020 Where Parody Meets Satire: Crossing the Line with “Lady Addle” 2

Polysèmes Revue d’études intertextuelles et intermédiales 23 | 2020 Contemporary Victoriana - Women and Parody Where Parody Meets Satire: Crossing the Line with “Lady Addle” Quand la parodie rencontre la satire : “Lady Addle“ dépasse les limites Margaret D. Stetz Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/polysemes/7691 DOI: 10.4000/polysemes.7691 ISSN: 2496-4212 Publisher SAIT Electronic reference Margaret D. Stetz, « Where Parody Meets Satire: Crossing the Line with “Lady Addle” », Polysèmes [Online], 23 | 2020, Online since 30 June 2020, connection on 02 July 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/polysemes/7691 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/polysemes.7691 This text was automatically generated on 2 July 2020. Polysèmes Where Parody Meets Satire: Crossing the Line with “Lady Addle” 1 Where Parody Meets Satire: Crossing the Line with “Lady Addle” Quand la parodie rencontre la satire : “Lady Addle“ dépasse les limites Margaret D. Stetz 1 For scholars of humour, there is a certain fascination in studying parodies that are now little known, especially if once they were well known. Why, we want to ask, were they popular in an earlier time? To whom did they appeal and why? What might these works say to us today? In the case of a series of four works of fiction produced by Mary Dunn (1900-1958), a British writer for the satirical magazine Punch, a second set of questions arises. These same four volumes, each one purporting to be written by a fictional British aristocrat named “Lady Addle”, were published from the mid-1930s through the late 1940s, but were reprinted in the 1980s and enjoyed both a second wave of sales in British bookshops and enthusiastic reviews in British periodicals. -

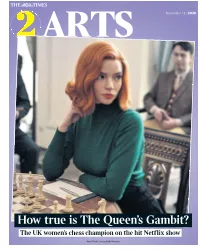

How True Is the Queen's Gambit?

ARTS November 13 | 2020 How true is The Queen’s Gambit? The UK women’s chess champion on the hit Netflix show Anya Taylor-Joy as Beth Harmon 2 1GT Friday November 13 2020 | the times times2 Caitlin 6 4 DOWN UP Moran Demi Lovato Quote of It’s hard being a former Disney child the Weekk star. Eventually you have to grow Celebrity Watch up, despite the whole world loving And in New!! and remembering you as a cute magazine child, and the route to adulthood the Love for many former child stars is Island star paved with peril. All too often the Priscilla way that young female stars show Anyabu they are “all grown up” is by Going revealed her Sexy: a couple of fruity pop videos; preferred breakfast, 10 a photoshoot in PVC or lingerie. which possibly 8 “I have lost the power of qualifies as “the most adorableness, but I have gained the unpleasant breakfast yet invented DOWN UP power of hotness!” is the message. by humankind”. Mary Dougie from Unfortunately, the next stage in “Breakfast is usually a bagel with this trajectory is usually “gaining cheese spread, then an egg with grated Wollstonecraft McFly the power of being in your cheese on top served with ketchup,” This week the long- There are those who say that men mid-thirties and putting on 2st”, she said, madly admitting with that awaited statue of can’t be feminists and that they cannot a power that sadly still goes “usually” that this is something that Mary Wollstonecraft help with the Struggle. -

The Performance of Intersectionality on the 21St Century Stand-Up

The Performance of Intersectionality on the 21st Century Stand-Up Comedy Stage © 2018 Rachel Eliza Blackburn M.F.A., Virginia Commonwealth University, 2013 B.A., Webster University Conservatory of Theatre Arts, 2005 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Theatre and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Chair: Dr. Nicole Hodges Persley Dr. Katie Batza Dr. Henry Bial Dr. Sherrie Tucker Dr. Peter Zazzali Date Defended: August 23, 2018 ii The dissertation committee for Rachel E. Blackburn certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Performance of Intersectionality on the 21st Century Stand-Up Comedy Stage Chair: Dr. Nicole Hodges Persley Date Approved: Aug. 23, 2018 iii Abstract In 2014, Black feminist scholar bell hooks called for humor to be utilized as political weaponry in the current, post-1990s wave of intersectional activism at the National Women’s Studies Association conference in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Her call continues to challenge current stand-up comics to acknowledge intersectionality, particularly the perspectives of women of color, and to encourage comics to actively intervene in unsettling the notion that our U.S. culture is “post-gendered” or “post-racial.” This dissertation examines ways in which comics are heeding bell hooks’s call to action, focusing on the work of stand-up artists who forge a bridge between comedy and political activism by performing intersectional perspectives that expand their work beyond the entertainment value of the stage. Though performers of color and white female performers have always been working to subvert the normalcy of white male-dominated, comic space simply by taking the stage, this dissertation focuses on comics who continue to embody and challenge the current wave of intersectional activism by pushing the socially constructed boundaries of race, gender, sexuality, class, and able-bodiedness. -

Birmingham Cover

Warwickshire Cover Online.qxp_Warwickshire Cover 23/09/2015 11:38 Page 1 THE MIDLANDS ULTIMATE ENTERTAINMENT GUIDE WARWICKSHIRE ’ Whatwww.whatsonlive.co.uk sOnISSUE 358 OCTOBER 2015 MEERA SYAL TALKS ABOUT ANITA AND ME AT THE REP GRAND DESIGNS contemporary home show at the NEC INSIDE: FILM COMEDY THEATRE LIVE MUSIC VISUAL ARTS EVENTS FOOD & DRINK & MUCH MORE! HANDBAGGED Moira Buffini’s comedy visits the Midlands interview inside... REP (FP) OCT 2015.qxp_Layout 1 21/09/2015 10:32 Page 1 Contents October Region 1 .qxp_Layout 1 21/09/2015 21:49 Page 1 October 2015 Strictly Nasty Craig Revel Horwood dresses for Annie Read the interview on page 42 Jason Donovan Moira Buffini Grand Designs stars in Priscilla Queen Of The talks about Handbagged Kevin McCloud back at the NEC Desert page 27 interview page 11 page 69 INSIDE: 4. News 11. Music 24. Comedy 27. Theatre 44. Dance 51. Film 63. Visual Arts 67. Days Out 81. Food @whatsonbrum @whatsonwarwicks @whatsonworcs Birmingham What’s On Magazine Warwickshire What’s On Magazine Worcestershire What’s On Magazine Publishing + Online Editor: Davina Evans [email protected] 01743 281708 ’ Sales & Marketing: Lei Woodhouse [email protected] 01743 281703 Chris Horton [email protected] 01743 281704 WhatsOn Editorial: Brian O’Faolain [email protected] 01743 281701 Lauren Foster [email protected] 01743 281707 MAGAZINE GROUP Abi Whitehouse [email protected] 01743 281716 Adrian Parker [email protected] 01743 281714 Contributors: Graham Bostock, James Cameron-Wilson, Chris Eldon Lee, Heather Kincaid, Katherine Ewing, Helen Stallard Offices: Wynner House, Managing Director: Paul Oliver Publisher and CEO: Martin Monahan Graphic Designers: Lisa Wassell Chris Atherton Bromsgrove St, Accounts Administrator: Julia Perry [email protected] 01743 281717 Birmingham B5 6RG This publication is printed on paper from a sustainable source and is produced without the use of elemental chlorine. -

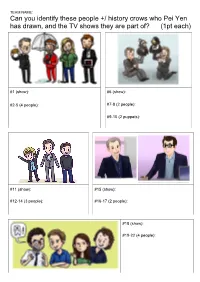

Acms Quiz – 2017

TEAM NAME: Can you identify these people +/ history crows who Pei Yen has drawn, and the TV shows they are part of? (1pt each) #1 (show): #6 (show): #2-5 (4 people): #7-8 (2 people): #9-10 (2 puppets): #11 (show): #15 (show): #12-14 (3 people): #16-17 (2 people): #18 (show): #19-22 (4 people): TEAM NAME: Can you identify these 2005 cartoon boys & their creator? (1pt each) 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) 6) 9) 7) 8) 10) TEAM NAME: Round #1 - Shows /15 pts Round #2 - Map /10 pts 1. 1. 2a. 2. 3. 2b. 4. 3a. 5. 6. 3b. 7. 3c. 8. 9. 4. 10. 5. 6. Round #3 - Fakes /10 pts 7a. 1. 7b. 2. 3. 8. 4. 9. 5. 10a. 6. 10b. 7. 8. 1 point for a complete right answer, 1/2 point 9. for getting it half right, 0 points for FAILURE* 10. * ignoble failure Round #4 - Award Winners /15 pts Round #5 - Venues /10 pts 1. 1. 2. 2. 3. 3. 4. 4. 5. 5. 6. 6. 7a. 7. 8. 7b. 9. 7c. 10. 7d. Round #6 - Names /10 pts 1. 8. 2. 9. 3. 10a. 4. 10b. 5. 10c. 6. 7. PLEASE DRAW US A CAT, IN THE 8. EVENT OF A TIE IT WILL 9. BE USED TO JUDGE 10. THE WINNER Round # /10 pts Round # /10 pts 1. 1. 2. 2. 3. 3. 4. 4. 5. 5. 6. 6. 7. 7. 8. 8. 9. 9. 10. 10. Round # /10 pts Round # /10 pts 1. 1. 2. 2. -

NETFLIX – CATALOGO USA 20 Dicembre 2015 1. 009-1: the End Of

NETFLIX – CATALOGO USA 20 dicembre 2015 1. 009-1: The End of the Beginning (2013) , 85 imdb 2. 1,000 Times Good Night (2013) , 117 imdb 3. 1000 to 1: The Cory Weissman Story (2014) , 98 imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 4. 1001 Grams (2014) , 90 imdb 5. 100 Bloody Acres (2012) , 1hr 30m imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 6. 10.0 Earthquake (2014) , 87 imdb 7. 100 Ghost Street: Richard Speck (2012) , 1hr 23m imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 8. 100, The - Season 1 (2014) 4.3, 1 Season imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 9. 100, The - Season 2 (2014) , 41 imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 10. 101 Dalmatians (1996) 3.6, 1hr 42m imdbClosed Captions: [ 11. 10 Questions for the Dalai Lama (2006) 3.9, 1hr 27m imdbClosed Captions: [ 12. 10 Rules for Sleeping Around (2013) , 1hr 34m imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 13. 11 Blocks (2015) , 78 imdb 14. 12/12/12 (2012) 2.4, 1hr 25m imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 15. 12 Dates of Christmas (2011) 3.8, 1hr 26m imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 16. 12 Horas 2 Minutos (2012) , 70 imdb 17. 12 Segundos (2013) , 85 imdb 18. 13 Assassins (2010) , 2hr 5m imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 19. 13 Going on 30 (2004) 3.5, 1hr 37m imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 20. 13 Sins (2014) 3.6, 1hr 32m imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 21. 14 Blades (2010) , 113 imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 22. -

Spring 2017 Summer Summer

SUMMERSUMMERSPRING 2017 / 3 SOMETHINGSOMETHINGSOMETHINGSOMETHING TOTOTOTO TO THEATRE SOMETHINGSOMETHING TO TO SOMETHINGMAKEMAKEMAKEMAKEMAKE YOUYOUYOUYOUYOU YOU FEELFEELFEELFEEL FEELTO MAKE MAKEUPLIFTED, YOU FEEL PLAYFUL, YOUUPLIFTED,UPLIFTED,UPLIFTED, FEEL UPLIFTED, PLAYFUL, PLAYFUL,PLAYFUL,PLAYFUL, WONDER, CAPTIVATED, THEATRE AD INFINITUM PRESENTS PLAYFUL,WONDER,AMAZED,WONDER,WONDER, WONDER, CAPTIVATED, CAPTIVATED,CAPTIVATED, The Devil WONDER, CAPTIVATED, 3for Bucket List 3for WONDER, CAPTIVATED, Speaks True 2 2 ECCLESIA PRESENTS TUE 25 APR 8PM THU 20 APR MOVED, SURPRISED, 6PM & 8.30PM CAPTIVATED,MOVED,MOVED,MOVED, SURPRISED,SURPRISED,SURPRISED, MOVED, Hidden The powerful story MOVED, SURPRISED, of one Mexican MOVED, SURPRISED, FRI 21 & SAT 22 APR 8PM MOVED, SURPRISED, A chilling exploration woman’s fight for of the psychological A play about finding the justice. TOGETHER, effects of war. TOGETHER, courage to face the truth When her mother SURPRISED,CONNECTED,TOGETHER, TOGETHER, Using wireless headphones, TOGETHER, of who you are. is murdered for TOGETHER,TOGETHER, 360 degree binaural sound protesting corporate and design and sometimes Set against the collapse governmental corruption, complete darkness, the real of the economic bubble in ENTERTAINED. 2008, Hidden is a love story Milagros finds herself words of ex-servicemen ENTERTAINED.ENTERTAINED. with only a bloodstained ENTERTAINED.ENTERTAINED. about invisible disability ENTERTAINED. are cut with the text of ENTERTAINED. list of those responsible. ENTERTAINED. in difficult times. Chris is a Shakespeare’s Macbeth Determined to make to investigate the return city lawyer; Jess is a PhD them pay, Milagros home from conflict student. On the surface, they’re embarks on a passionate zones. Projection, scent, just two ordinary people in quest for justice, no light and dance convey a relationship who want to matter the cost. -

May All Our Voices Be Heard

JUST THE TONIC EDFRINGE VENUES 2019 FULL LISTINGS AND MORE 1st - 25th August 2019 EDINBURGH FRINGE PROUDLY SPONSORED BY NO ONE - TOTALLY INDEPENDENT 7 venues 8 Bars 4000 performances 98.9%* 19 performance spaces 182 shows comedy *THE OTHER 1.1% ARE FUN AS WELL… CHALLENGE: GO FIND THE OTHER 2 SHOWS INSIDE! MAY ALL OUR VOICES BE HEARD www.justthetonic.com Big Value is the best Big Value compilation show at The Fringe. It’s an Comedy Shows excellent barometer of The longest running stand up compilation show on the fringe. We ask promoter people who are going Darrell Martin to take a look at at it’s fine heritage. to go on to big things. Starting in 1996, with a line up that included The show is currently produced by Darrell And I’m not just saying Milton Jones and Adam Bloom, the Big Value Martin, who runs Just the Tonic. It wasn’t Comedy Shows have been selecting the always that way. Many years ago Darrell was that because I did it. stars of the future for almost 25 years. a keen performer that was desperate to be part of the show. Comedians such as Jim Jeffries, Pete Harris was the person who set it all up. Sarah Millican, Jon Richardson and He ran a chain of clubs called Screaming ROMESH Romesh Ranganathan are some of Blue Murder. According to Adam Bloom, it all RANGANATHAN came out of a conversation where Adam said Big Value Comedy Show 2011 + 2012 those who were first exposed to the to Pete that he wanted to go to Edinburgh but couldn’t afford it. -

Let's Drive a Blundabus Through the Heart of Comedy?!

Let’s Drive a BlundaBus through the heart of Comedy?! “What is a BlundaBus?” I hear you ask… It’s a double-decker venue full of creativity & Joy that can pop-up anywhere! “Spirit of the Fringe…” The Guardian ABOUT THE BLUNDABUS The BlundaBus is an award-winning pop-up Comedy Theatre & Bar on a converted double-decker Bus. Created by comedian Bob Slayer, the BlundaBus appears at Fringe, Festivals, Comedy Festivals, Music Festivals, Breweries, Your House… Anywhere it’s invited and Everywhere it’s not! On 4th July 2015 (Independence Day) we took delivery of an ex-London double decker. We converted it into a 45 capacity mini theatre on the top deck with a bar / ticket office in the saloon below. The BlundaBus has since appeared all around the UK and even Norway and Ireland is booked in. Previous Acts Include: Stewart Lee, Phil Kay, Paul Foot, Bobby Mair, Tim Renkow, Sofie Hagen, Adam Hess, Norman Lovett, Spencer Jones, Patrick Monahan, Tony Law, Josh Ladgrove, Simon Munnery, Bob Slayer… Festivals Include: Edinburgh Fringe, Leicester Comedy Festival, Glasgow Comedy Festival, Nottingham Comedy Festival, Croydon Comedy Festival, Bergen Humorfest (Norway), Stavanger Comedy Festival (Norway), Livestock Festival, Musicport, Brew In The Bog Festival, Kelburn Festival etc Breweries Include: Born In The Borders, Castle Rock Nottingham, Howardtown etc… WHO IS YOUR DRIVER? BOB SLAYER is an award-winning Comedian, storyteller and maverick Fringe promoter... Bob started life as a Jockey but multiple injuries and increasing weight caused him to retire from the saddle. He became a rock & Roll tour manager who The NME described as: "Wilder than the acts he looked after" (Snoop Dogg, Bloodhound Gang, Electric Eel Shock)..