Library Trends V.57, No.1 Summer 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By Philip Roth

The Best of the 60s Articles March 1961 Writing American Fiction Philip Roth December 1961 Eichmann’s Victims and the Unheard Testimony Elie Weisel September 1961 Is New York City Ungovernable? Nathan Glazer May 1962 Yiddish: Past, Present, and Perfect By Lucy S. Dawidowicz August 1962 Edmund Wilson’s Civil War By Robert Penn Warren January 1963 Jewish & Other Nationalisms By H.R. Trevor-Roper February 1963 My Negro Problem—and Ours By Norman Podhoretz August 1964 The Civil Rights Act of 1964 By Alexander M. Bickel October 1964 On Becoming a Writer By Ralph Ellison November 1964 ‘I’m Sorry, Dear’ By Leslie H. Farber August 1965 American Catholicism after the Council By Michael Novak March 1966 Modes and Mutations: Quick Comments on the Modern American Novel By Norman Mailer May 1966 Young in the Thirties By Lionel Trilling November 1966 Koufax the Incomparable By Mordecai Richler June 1967 Jerusalem and Athens: Some Introductory Reflections By Leo Strauss November 1967 The American Left & Israel By Martin Peretz August 1968 Jewish Faith and the Holocaust: A Fragment By Emil L. Fackenheim October 1968 The New York Intellectuals: A Chronicle & a Critique By Irving Howe March 1961 Writing American Fiction By Philip Roth EVERAL winters back, while I was living in Chicago, the city was shocked and mystified by the death of two teenage girls. So far as I know the popu- lace is mystified still; as for the shock, Chicago is Chicago, and one week’s dismemberment fades into the next’s. The victims this particular year were sisters. They went off one December night to see an Elvis Presley movie, for the sixth or seventh time we are told, and never came home. -

Alfred A. Knopf

Alfred A. Knopf Publisher of Borzoi Books Fall 2009 22112_K-Fa09_f_MM.qxp:K-Fa09_1p_r1 3/6/09 3:21 PM Page 43 Alfred A.Knopf Index of Titles Page Page The American Civil War, John Keegan 85 Lincoln, Life-Size, Philip B. Kunhardt III, American Icon, Teri Thompson, Peter W. Kunhardt, and Peter W. Nathaniel Vinton, Michael O’Keeffe, and Kunhardt, Jr. 89 Christian Red 46 The Museum of Innocence, Orhan Pamuk 83 Angel Time, Anne Rice 79 The National Parks, Dayton Duncan and The Art Student’s War, Brad Leithauser 94 Ken Burns 55 The Bauhaus Group, Nicholas Fox Weber 78 News of the World, Philip Levine 74 Blood’s A Rover, James Ellroy 63 Noah’s Compass, Anne Tyler 61 The Case for God, Karen Armstrong 57 Nocturnes, Kazuo Ishiguro 53 The Children’s Book, A. S. Byatt 69 Nothing Was the Same, Kay Redfield Civil War Wives, Carol Berkin 64 Jamison 65 The Complete Lyrics of Johnny Mercer, On Thin Ice, Richard Ellis* 92 Johnny Mercer 80 The Original of Laura, Vladimir Nabokov 97 Conquering Fear, Harold S. Kushner 81 Painting Below Zero, James Rosenquist 86 Conversations with Woody Allen, Eric Lax 52 A Phone Call to the Future, Mary Jo Crossers, Philip Caputo 76 Salter 54 Crude World, Peter Maass 58 The Pleasures of Cooking for One, The Death of Ivan Ilyich and Other Judith Jones 62 Stories, Leo Tolstoy 98 The Queen Mother, William Shawcross 93 Defend the Realm, Christopher Andrew 77 Redeeming Features, Nicholas Haslam 96 Easy, Marie Ponsot 84 Robert Altman, Mitchell Zuckoff 73 Eating, Jason Epstein 82 Robert Redford, Michael Feeney Callan 95 The Education of a British-Protected Child, Chinua Achebe* 72 Selected Poems, Frank O’Hara 54 Endpoint and Other Poems, John Updike 45 The Sibley Guide to Bird Life and Behavior, David Allen Sibley 48 A Gate at the Stairs, Lorrie Moore 59 The Slippery Year, Melanie Gideon 51 The Godfather of Kathmandu, John Burdett 75 Sweet Thunder, Wil Haygood* 68 Half the Sky, Nicholas D. -

Complete 8.2.Qxd

NOTESVolume 8, Number 2, March 2001 E THE NEW YORK SOCIETY LIBRARY BOOK AWARDS, 2000 D The New York Society Library Book Awards were established in 1996 to honor current authors who capture the essence of New York City. This year’s jury comprises Constance Rogers Roosevelt, Chair; Richard B. Bernstein, Barbara Cohen, Joan K. Davidson, Hope Cooke, Christopher Gray, Tom Mellins, Roger Pasquier, Elizabeth Barlow Rogers, Jean Strouse, and Wendy Wasserstein. The 2000 Book Awards will be presented Wednesday, May 2 at 5:30 P.M. in the Members’ Room. The presenters will be Wendy Wasserstein, Eric Foner, Christopher Lehmann-Haupt, Elizabeth Barlow Rogers, Christopher Gray, and Tony Hiss. Library members are cordially invited to the award ceremony and reception, but space is limited. Reservations must be placed with the Events Office (212-717-0357) by April 26. E AWARD FOR LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT D E AWARD FOR FICTION D Vincent Seyfried, The Amazing Adventures Historian Seyfried’s monu- of Kavalier and Clay Weber-Ziel mental work Michael Chabon focuses on Queens before it (Random House) became part of greater New “The depth of Chabon's thought, his York and on the history of sharp language, his inventiveness and the Long Island Rail Road. his ambition make this a novel of Christopher Gray calls him towering achievement.” “the grand old man of -The New York Times Book Review From Seyfried’s Queens: A Pictorial E AWARD FOR HISTORY D E AWARD FOR NATURAL HISTORY D Working-Class New York: Heartbeats in the Muck: The Life and Labor Since History, Sea Life, and World War II Environment Joshua B. -

Contributors

Contributors Mashey Bernstein holds a PhD in American Literature from the University of California, Santa Barbara, where he currently teaches in the Writing Program and in the Film and Media Studies Department. He has written extensively on Mailer in The Mailer Review, Studies in American-Jewish Literature, the San Francisco Review of Books, and the London Jewish Chronicle. He also writes on film, especially Jewish aspects of the media. Scott Duguid is in the process of completing his Doctoral Thesis on Norman Mailer and the aesthetics/politics of the avant-garde at the University of Edinburgh. His interests include twentieth-century fic- tion, with a particular focus on America; intersections between liter- ature and art history; theories of modernism and postmodernism. He has published articles on Norman Mailer, and on Warhol’s films. Jason Epstein was Editorial Director at Random House for forty years, where he developed the Vintage paperbacks series and pub- lished Norman Mailer, Vladimir Nabokov, E.L. Doctorow, Gore Vidal, Philip Roth, Elaine Pagels, and Richard Holbrook. In 1952 he created the Anchor Books imprint; in 1963 he cofounded the New York Review of Books, and in 1979 he became one of the cofounders of the Library of America, which was intended to market archival quality editions of American classic literature. The first volumes were published in 1982, and the company now prints about 250,000 vol- umes per year. Epstein is the first winner of the National Book Award for Distinguished Service to American Letters (1988) and, in 2007, he has won the Philolexian Award for Distinguished Literary Achievement. -

Proofs of Genius: Collected Editions from the American Revolution to the Digital Age, by Amanda Gailey Revised Pages

Revised Pages Proofs of Genius Revised Pages editorial theory and literary criticism George Bornstein, Series Editor Palimpsest: Editorial Theory in the Humanities, edited by George Bornstein and Ralph G. Williams Contemporary German Editorial Theory, edited by Hans Walter Gabler, George Bornstein, and Gillian Borland Pierce The Hall of Mirrors: Drafts & Fragments and the End of Ezra Pound’s Cantos, by Peter Stoicheff Emily Dickinson’s Open Folios: Scenes of Reading, Surfaces of Writing, by Marta L. Werner Scholarly Editing in the Computer Age: Theory and Practice, Third Edition, by Peter L. Shillingsburg The Literary Text in the Digital Age, edited by Richard J. Finneran The Margins of the Text, edited by D. C. Greetham A Poem Containing History: Textual Studies in The Cantos, edited by Lawrence S. Rainey Much Labouring: The Texts and Authors of Yeats’s First Modernist Books, by David Holdeman Resisting Texts: Authority and Submission in Constructions of Meaning, by Peter L. Shillingsburg The Iconic Page in Manuscript, Print, and Digital Culture, edited by George Bornstein and Theresa Tinkle Collaborative Meaning in Medieval Scribal Culture: The Otho Laȝamon, by Elizabeth J. Bryan Oscar Wilde’s Decorated Books, by Nicholas Frankel Managing Readers: Printed Marginalia in English Renaissance Books, by William W. E. Slights The Fluid Text: A Theory of Revision and Editing for Book and Screen, by John Bryant Textual Awareness: A Genetic Study of Late Manuscripts by Joyce, Proust, and Mann by Dirk Van Hulle The American Literature Scholar in the Digital Age, edited by Amy E. Earhart and Andrew Jewell Publishing Blackness: Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850, edited by George Hutchinson and John K. -

Fictionwise/Ereader - List of Unmatched Titles

Fictionwise/eReader - List of Unmatched Titles Title Author Publisher 'Twas the Night Before Christmas [From the New Adventures of Sherlock Holmes] Dennis Green Boondock Books 'Twixt Land and Sea Joseph Conrad EbooksLib 'Twixt Land and Sea Tales Joseph Conrad PDM Classics ...And Dreams Are Dreams: A Novel in Seven Parts Vassilis Vassilikos Random House, Inc. ...And Dreams Are Dreams: A Novel in Seven Parts Vassilis Vassilikos Random House, Inc. ...To End All War [The Survivalist #21] Jerry Ahern Jerry Ahern ...Was Yesterday Robert E. Brisbin CyberRead 1...2...3...Count With Me Leta Nolan Childers DiskUs Publishing 10 Insider Secrets Career Transition Workshop: Your Complete Guide to Discovering the Ideal Job Todd Bermont 10 Step Corporation 10 Insider Secrets To Job Hunting Success: Everything You Need To Get The Job You Want In 24 Hours--Or Less! Todd L. Bermont Publishing Dimensions 10 Reasons to Abolish the IMF & World Bank Kevin Danaher Random House, Inc. 10 Reasons to Abolish the IMF and the World Bank Kevin Danaher Random House, Inc. 10 Secrets to Successful Home Buying and Selling Lois A. Vitt Financial Times Prentice Hall 10 Steps To Success In Direct Sales Bussiness Reports CyberRead 10,000 Dreams Interpreted Gustavus Miller World Digital Library 10-Minute Talks Jonathan Mckee Harper Collins, Inc. 100 Bullshit Jobs ... And How to Get Them Stanley Bing Harper Collins, Inc. 100 Days in the Secret Place Gene Edwards Treasures Media Inc 100 Haiku Francis Gallagher Iumix Limited 100 Rants on Why Men Are Pants Amy Charter Summersdale Publishers Ltd 100 Super Supplements for a Longer Life Frank Murray McGraw-Hill Companies 100 Thematic Word Search Puzzles John F. -

Hannah Arendt on Violence Mary Beard on Cleopatra Ian Buruma: Tibet Disenchanted Michael Chabon on Richard Price Noam Chomsky: a Visit to Laos J.M

Hannah Arendt on Violence Mary Beard on Cleopatra Ian Buruma: Tibet Disenchanted Michael Chabon on Richard Price Noam Chomsky: A Visit to Laos J.M. Coetzee on Goethe Mark Danner on Bosnia Joan Didion: In El Salvador Freeman Dyson: The Scientist as Rebel M.F.K. Fisher: The Indigestible Nadine Gordimer: Letter from South Africa Graham Greene on Panama Tony Judt on Social Democracy George Kennan: Gorbachev Norman Mailer on Last Tango in Paris Hilary Mantel on Marie Antoinette Mary McCarthy on Watergate Daniel Mendelsohn on Mad Men Joyce Carol Oates on Flannery O’Connor Robert Oppenheimer on Albert Einstein Charles Rosen on Mozart Zadie Smith: Two Paths for the Novel Susan Sontag on Photography Editorial Profile “ The most serious literary publication in the world, independent, resistant to every pressure, to every clique, publishing leading articles on literary fiction as often as on ideas, written by renowned authors and essayists.” —Le Monde The New York Review of Books began and Mary McCarthy. The magazine was “of more cul- during the long news blackout of the New York tural import than the opening of Lincoln Center,” publishing strike in 1963. A group of friends, includ- announced The New Statesman, while the great English ing the editors, Robert Silvers and Barbara Epstein, art historian Kenneth Clark observed, “I have never decided to create a new kind of magazine—one in known such a high standard of reviewing.” which the most interesting and lively minds they could find would discuss current books and issues Since then, every two weeks for five decades The New in depth, and with all the authority and knowledge York Review has continued to pose the central issues they possessed. -

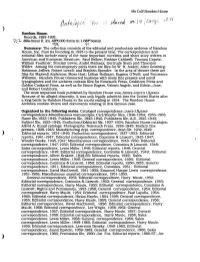

Summary: the Collection Consists of the Editorial and Production Archives of Random House, Inc

Ms CollXRandom House Random House. Records, 1925-1992. £9**linearft. (ca.-Q&F,000 items in 1,657-boxes) 13 % SI Summary: The collection consists of the editorial and production archives of Random House, Inc. from its founding in 1925 to the present time. The correspondence and editorial files include many of the most important novelists and short story writers in American and European literature: Saul Bellow; Erskine Caldwell; Truman Capote; William Faulkner; Sinclair Lewis; Andre Malraux; Gertrude Stein and Thornton Wilder. Among the contemporary poets there are files for W. H. Auden; Allen Ginsberg; Robinson Jeffers; Robert Lowell; and Stephen Spender. In the area of theater there are files for Maxwell Anderson; Moss Hart; Lillian Hellrnan; Eugene O'Neill; and Tennessee Williams. Random House transacted business with many fine presses and noted typographers and the archives contain files for Nonesuch Press, Grabhorn Press and Golden Cockerel Press, as well as for Bruce Rogers, Valenti Angelo, and Edwin, Jane, and Robert Grabhorn. The most important book published by Random House was James Joyce's Ulysses. Because of its alleged obscenity, it was only legally admitted into the United States after a long battle by Random House in the courts ending in 1934. The Random House Archives contain letters and documents relating to this famous case. Organized in the following series: Cataloged correspondence; Joyce-Ulysses correspondence;Miscellaneous manuscripts; Cerf/Klopfer files, 1946-1954; 1956-1965; Name file, 1925-1945; Publishers file, 1925-1945; Publishers file, A-Z, 1925-1945; Subject file, 1925-1945; Production/Editorial file, 1927-1934; Random House cataloges; Alfred A Knopf catalogs; Photographs; Nonesuch Press, 1928-1945; Modem fine presses, 1928-1945; Manufacturing dept. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Our Gang by Philip Roth Our Gang — Philip Roth

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Our Gang by Philip Roth Our Gang — Philip Roth. A ferocious political satire in the great tradition, Our Gang is Philip Roth’s brilliantly indignant response to the phenomenon of Richard M. Nixon. In the character of Trick E. Dixon, Roth shows us a man who outdoes the severest cynic, a peace-loving Quaker and believer in the sanctity of human life who doesn’t have a problem with killing unarmed women and children in self-defense. A master politician with an honest sneer, he finds himself battling the Boy Scouts, declaring war on Pro-Pornography Denmark, all the time trusting in the basic indifference of the voting public. Nixon. A TIGHTWAD JOHN KENNEDY refusing to buy his motorcade gas at a service station that doesn't give green stamps--such was one of the opening shots of liberal political satire in the 1960's. Vaughn Meader's impersonation of Kennedy on his album The First Family embodied two traditional characteristics of humorous caricature and parody. The imitation bore a superficial resemblance to its subject while the content made us aware that the impression was not the original. It felt good to laugh at a caricature that in its own ludicrous way reduced Kennedy to understandable human terms. Yet, we didn't need to feel that we were being disrespectful the very silliness of the situation assured us that we were laughing with not at the President. The style of anti-Nixon satire in the 1970's stems from less generous sentiments. Nixon's public unease, his failure to display any emotion besides anger, his continued harping on the traditional virtues of America, his self-conscious piety, and above all his continual deceitfulness have turned him into a caricature of himself in the eyes of those liberals who constitute an audience for political humor. -

ROBERT B. SILVERS Cofundador Y Editor De the New York Review of Books

ROBERT B. SILVERS Cofundador y Editor de The New York Review of Books 185 BUSCAMOS LITERATURA CON LUZ PROPIA, LA BELLEZA DE LA ESCRITURA The New York Review of Books es la revista de libros más importante del mundo y Robert Silvers es su profeta. No ejerce ese poder como un magnate, ni como un arrogante editor, ni como el artífice de un imperio del gusto literario; en realidad, lo ejerce como un lector, curioso hasta la extenuación, interesado por todos los asuntos que su revista, que ya tiene casi medio siglo, aborda cada mes, en su versión de papel y en su desarrollo en la Red. Él le presta atención a las dos partes de esa misma cabeza, la digital y la impresa, acaso porque su mente, que nace de este mundo de blanco y negro del que parten la escritura y su generación, se ha adaptado en seguida a un nuevo desafío. No lo aborda con miedo o con estupefacción, sino con naturalidad. Cree que en algún momento Gutenberg y lo cibernético van a co- existir en un espacio cultural en el que crezca la comprensión mutua entre lo llamado viejo, que fue nuevo, y lo llamado nuevo, que en algún momento será viejo también. Una conversación con este hombre fascina no solo porque haya tras él una experiencia que lo hace legendario, como a su revista, sino porque mantiene esa curiosidad que expresa The New York Review of Books con la pasión con que debió poner en marcha este proyecto. Desde su inicio, The New York Review of Books hizo de la indepen- dencia (respecto a los autores y a los editores) su caballo de batalla in- telectual; y es que no podía ser de otra manera. -

Jason Epstein at the 2008 Hong Kong Book Fair

ON DEMAND BOOKS Speech given by Jason Epstein at the 2008 Hong Kong Book Fair I would like to talk tonight, if I may, about my career in book publishing which began almost sixty years ago and shows no sign of coming to an end, at least not until I do. To tell you everything that happened either to me or because of me in the book business during those sixty years would take another sixty years. So I shall tell you only about that aspect of my career that explains all the rest. That aspect is backlist, for publishing could not exist without backlist and as I shall argue, neither could you or I. Backlist is a publisher’s most important asset: titles that have covered their initial costs, earned out the authors’ advances, require no further investment except the cost of making and shipping the book itself and which sell steadily year after year without advertising or significant sales expense. Without a substantial list of such titles a publisher cannot survive. The same can be said of a civilization, for the books that survive the test of time, books that are treasured and read year after year, are humanity’s backlist, our collective brain. I do not refer simply to the classics of our various traditions but also to the more recent books, hundreds of which are published every year and join the backlist if not permanently at least long enough to move the process forward, provide depth and complexity to our understanding for those who seek it. -

According to Jason Epstein (Review of Book Business by Jason Epstein W W Norton & Company, 2001 Pp 188 ISBN 0 393 04981 1 $21.95)

LOGOS 12(2) 3rd/JH 1/11/06 9:47 am Page 87 LOGOS Publishing’s brave new world – according to Jason Epstein (Review of Book Business by Jason Epstein W W Norton & Company, 2001 pp 188 ISBN 0 393 04981 1 $21.95) Stephen Horvath A recent symposium in the Los Angeles Times Book Review considered the question “Is Publishing Dead?” Contributions from thirty-seven veterans of the book wars were prefaced by a review of two new books by participants in the Times forum – André Schiffrin’s The Business of Books (reviewed in LOGOS 11/4) and Jason Epstein’s Book Business. The attention to Epstein’s book was the latest in a After twenty years in the quite remarkable series of exposures–remarkable, at publishing business, during least, for a slight volume of markedly hybrid form: which he worked for a US memoir and essay, history and prophetic conjecture. educational publisher, for an It began as a lecture given at the New York Public Library in 1999, which became a lengthy article in international STM publisher and the New York Review of Books (where I first came as a publisher of academic and across it), followed by another article therein, then professional journals, Steve the widely reviewed book, featured in the LA Times Horvath entered bookselling with symposium and the subject of much commentary in other major media. Barnes & Noble. Recently he Taking my cue from previously published was Assistant Manager of the assessments, I feel obliged to begin by eulogizing Mr Borders Superstore in San Epstein’s career achievements.