HUBLEY-DISSERTATION-2015.Pdf (9.140Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amjad Ali Khan & Sharon Isbin

SUMMER 2 0 2 1 Contents 2 Welcome to Caramoor / Letter from the CEO and Chairman 3 Summer 2021 Calendar 8 Eat, Drink, & Listen! 9 Playing to Caramoor’s Strengths by Kathy Schuman 12 Meet Caramoor’s new CEO, Edward J. Lewis III 14 Introducing in“C”, Trimpin’s new sound art sculpture 17 Updating the Rosen House for the 2021 Season by Roanne Wilcox PROGRAM PAGES 20 Highlights from Our Recent Special Events 22 Become a Member 24 Thank You to Our Donors 32 Thank You to Our Volunteers 33 Caramoor Leadership 34 Caramoor Staff Cover Photo: Gabe Palacio ©2021 Caramoor Center for Music & the Arts General Information 914.232.5035 149 Girdle Ridge Road Box Office 914.232.1252 PO Box 816 caramoor.org Katonah, NY 10536 Program Magazine Staff Caramoor Grounds & Performance Photos Laura Schiller, Publications Editor Gabe Palacio Photography, Katonah, NY Adam Neumann, aanstudio.com, Design gabepalacio.com Tahra Delfin,Vice President & Chief Marketing Officer Brittany Laughlin, Director of Marketing & Communications Roslyn Wertheimer, Marketing Manager Sean Jones, Marketing Coordinator Caramoor / 1 Dear Friends, It is with great joy and excitement that we welcome you back to Caramoor for our Summer 2021 season. We are so grateful that you have chosen to join us for the return of live concerts as we reopen our Venetian Theater and beautiful grounds to the public. We are thrilled to present a full summer of 35 live in-person performances – seven weeks of the ‘official’ season followed by two post-season concert series. This season we are proud to showcase our commitment to adventurous programming, including two Caramoor-commissioned world premieres, three U.S. -

The Jewish Museum and Bang on a Can Present ETHEL Performing the String Quartets of Julia Wolfe

The Jewish Museum and Bang on a Can Present ETHEL Performing the String Quartets of Julia Wolfe Photos by Matthew Murphy (ETHEL) and Peter Serling (Julia Wolfe) Thursday, February 28, 2019 at 7:30pm Scheuer Auditorium at the Jewish Museum 1109 5th Ave at 92nd St | New York, NY Tickets: $20 General; $16 Students and Seniors; $12 Jewish Museum Members Available at www.thejewishmuseum.org. Includes museum admission. New York, NY – Bang on a Can and the Jewish Museum’s 2018-2019 concert season, pairing innovative music with the Museum’s exhibitions and showcasing leading female performers and composers, continues on Thursday, February 28, 2019 at 7:30pm. The acclaimed string quartet ETHEL performs the complete string quartets of Pulitzer Prize-winning composer Julia Wolfe: Dig Deep, Early that Summer, Four Marys, and Blue Dress. This is the first performance of all of Wolfe's string quartets at one time, on one stage. Julia Wolfe's string quartets, as described by The New Yorker, "combine the violent forward drive of rock music with an aura of minimalist serenity [using] the four instruments as a big guitar, whipping psychedelic states of mind into frenzied and ecstatic climaxes." This performance is presented in conjunction with the exhibition of fellow New York City cultural icon Martha Rosler: Irrespective. Established in New York City in 1998, ETHEL quickly earned a reputation as one of America’s most adventurous string quartets. Twenty years later, the band continues to set the standard for contemporary concert music. ETHEL is Ralph Farris (viola), Kip Jones (violin), Dorothy Lawson (cello), and Corin Lee (violin). -

Multi-Percussion in the Undergraduate Percussion Curriculum Benjamin A

University of Miami Scholarly Repository Open Access Dissertations Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2014-12 Multi-percussion in the Undergraduate Percussion Curriculum Benjamin A. Charles University of Miami, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlyrepository.miami.edu/oa_dissertations Recommended Citation Charles, Benjamin A., "Multi-percussion in the Undergraduate Percussion Curriculum" (2014). Open Access Dissertations. Paper 1324. This Open access is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at Scholarly Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ! ! UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI ! ! MULTI-PERCUSSION IN THE UNDERGRADUATE PERCUSSION CURRICULUM ! By Benjamin Andrew Charles ! A DOCTORAL ESSAY ! ! Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Miami in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Coral Gables,! Florida ! December 2014 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ©2014 Benjamin Andrew Charles ! All Rights Reserved UNIVERSITY! OF MIAMI ! ! A doctoral essay proposal submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical! Arts ! ! MULTI-PERCUSSION IN THE UNDERGRADUATE PERCUSSION CURRICULUM! ! Benjamin Andrew Charles ! ! !Approved: ! _________________________ __________________________ -

Philippe LEROUX Y R a L a E H P O T S I R H C

Philippe LEROUX y r a l A e h p o t s i r h C : o t o h P Gérard Billaudot Éditeur Octobre 2014 P h i l i p p e L E R O U X ( 1 9 5 9 ) CATALOGUE DES ŒUVRES C ATALOGUE OF WORKS W ERKVERZEICHNIS C ATALOGO DE OBRAS 14 rue de l’Échiquier - 75010 PARIS - FRANCE Tél. : (33) 01.47.70.14.46 - Télécopie : (33) 01.45.23.22.54 www.billaudot.com [email protected] - [email protected] B I O G R A P H I E P H I L I P P E L E RO U X ( 1 9 5 9 ) Philippe Leroux entre au Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique de Paris en 1978 dans les classes d'Ivo Malec, Claude Ballif, Pierre Schäeffer et Guy Reibel où il obtient trois premiers prix. Durant cette période, il étudie également avec Olivier Messiaen, Franco Donatoni, Betsy Jolas, Jean-Claude Eloy et Iannis Xénakis. En 1993, il est nommé pensionnaire à la Villa Médicis où il séjourne jusqu'en octobre 1995. Il est l'auteur d'une soixantaine d'œuvres, symphoniques, acousmatiques, vocales, pour dispositifs électroniques, et de musique de chambre. Celles-ci lui ont été commandées par le Ministère français de la Culture, l'Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio-France, la Südwestfunk Baden-Baden, l'IRCAM, Les Percussions de Strasbourg, l'Ensemble Intercontemporain, l'Ensemble 2e2m, l'INA-GRM, le Nouvel Ensemble Moderne de Montreal, l'Ensemble Ictus, le Festival Musica, l'Ensemble BIT 20, la fondation Koussevitsky, l'Ensemble San Francisco Contemporary Music Players, l'Ensemble Athelas, l'Orchestre National de Lorraine, l'Orchestre Philharmonique de Nice, le CIRM, INTEGRA, le Festival Berlioz, ainsi que par d'autres institutions françaises et étrangères. -

Volume I (Final) Proofread

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Influence of Pop Music in the Works of Three Contemporary American Composers: Steven Mackey, Julia Wolfe and Nico Muhly Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5h4626dd Author Lee, Hyunjong Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Influence of Pop Music in the Works of Three Contemporary American Composers: Steven Mackey, Julia Wolfe and Nico Muhly A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctoral of Philosophy in Music by Hyunjong Lee 2014 © copyright by Hyunjong Lee 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Influence of Pop Music in the Works of Three Contemporary American Composers: Steven Mackey, Julia Wolfe and Nico Muhly by Hyunjong Lee Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Ian Krouse, Chair There are two volumes in this dissertation: the first is a monograph, and the second a musical composition, both of which are described below. Volume I These days, labels such as classical, rock and pop mean less and less since young musicians frequently blur boundaries between genres. These young musicians have built an alternative musical universe. I construct five different categories to explore this universe. They are 1) circuits of alternate concert venues, 2) cross-genre collaborations, 3) alternative modes of musical groups, 4) new compositional trends in classical chamber music, and 5) new ensembles and record labels. ii In this dissertation, I aim to explore these five categories, connecting them to recent cultural trends in New York. -

{Download PDF} Steppenwolf Ebook, Epub

STEPPENWOLF PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Hermann Hesse,David Horrocks | 272 pages | 05 Apr 2012 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780141192093 | English | London, United Kingdom Steppenwolf PDF Book Play album Buy Loading. Wikimedia Commons Wikiquote. Steppenwolf fights Wonder Woman. In October we gave our last performance. A Girl I Knew. Live In Louisville! Friday 2 October Wednesday 7 October Born to Be Wild. Wednesday 29 July Hermann Hesse. Release Date January 29, This episode confirms to Harry that he is, and will always be, a stranger to his society. Thursday 25 June Iron Butterfly. Romantic Sad Sentimental. Following Darkseid's orders, Steppenwolf invaded Earth about 5 thousand years before the Battle of Metropolis with and his vast army of Parademons and attempted to conquer the planet but were forced into their first retreat ever by the combined armies of the Humans , Amazons , Atlanteans , and the Olympian Gods , losing 3 Mother Boxes with him. The quality of the acting is also difficult to gauge because the interactions between characters are already supposed to be so far removed from the kinds of things that people in your life most likely say and do. Add image 10 more photos. Cancel Save. The… read more. Now with the 3 Mother Boxes on his power, Steppenwolf decided that it was time to seal the Earth's fate via destroying it as he did in the past with several other planets under the orders of Darkseid's Elite. Darkseid with Steppenwolf at his side led his forces to Earth in search of the Anti Life Equation , where he met resistance from an alliance of Old Gods , Humans , Amazons , Atlanteans and Lanterns , who stopped him from uniting the three Mother Boxes and turning the planet into a copy of Apokolips. -

World Watch One Newsletter Groups Have Popped up Since

Cover Art by Paul Gulacy WORLD WATCH ONE CHICAGO BUREAU OFFICE Introduction from the Editor Dan “Big Shoulders” Berger Libertyville, IL Page 1 What it was Like Back Then Dan Berger Pages 2-4 The Savage Breast Survival Kit Steve “Rainbow Kitty” Mattsson Portland, OR Page 5 Not Quite Perfect Enough Scott “Camelot” Tate Alamosa, CO Page 6 Team Banzai Travel Bug Update Steve Mattsson Page 7 Buckaroo Banzai Video Games Sean “Figment” Murphy Springfield, VA Pages 8-10 SPECIAL SECTION RICK WATCH ONE W.D. Richter Interview Dan Berger Pages 11-12 Another W.D. Richter Interview Steve Mattsson Pages 12-16 Yet Another W.D. Richter Interview Tim “Tim Boo Ba” Monro Renton, WA Pages 17-19 Portland, OR Screening Report Steve Mattsson Page 21 Raleigh, NC Screening Report Dan Berger Page 22 Retro Reviews Ed “El Pistolero Solitario” Mauser New Brunswick, NJ Pages 23-24 “Wild Asses of the Kush” review Tim Munro Page 25 “Of Hunan Bondage” review Tim Munro Pages 25-26 “A Tomb with a View” review Dan Berger Page 27 “A Tomb with a View” annotations Tim Munro Page 28 “Hardest of the Hard” review Scott Tate Pages 29-30 Banzai Rising at Moonstone Books Dan Berger Page 30 Nova Police & Death Dwarves: Origins Steve Mattsson Pages 31-32 Hanoi Shan/Timeline update Steve Mattsson Pages 33-34 SPECIAL INSERT BANZAI INSTITUTE ARCHIVAL DOCUMENTS World Economic Forum Transcript Earl Mac Rauch From Script to Screen Steve Mattsson Front Cover: One of the most dramatic images associated with Buckaroo Banzai is the art for the French version of the theatrical poster by artist Melki. -

News Release

news release FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE PRESS CONTACT: Maggie Stapleton, Jensen Artists September 25, 2019 646.536.7864 x2; [email protected] American Composers Orchestra Announces 2019-2020 Season Derek Bermel, Artistic Director & George Manahan, Music Director Two Concerts presented by Carnegie Hall New England Echoes on November 13, 2019 & The Natural Order on April 2, 2020 at Zankel Hall Premieres by Mark Adamo, John Luther Adams, Matthew Aucoin, Hilary Purrington, & Nina C. Young Featuring soloists Jamie Barton, mezzo-soprano; JIJI, guitar; David Tinervia, baritone & Jeffrey Zeigler, cello The 29th Annual Underwood New Music Readings March 12 & 13, 2020 at Aaron Davis Hall at The City College of New York ACO’s annual roundup of the country’s brightest young and emerging composers EarShot Readings January 28 & 29, 2020 with Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra May 5 & 6, 2020 with Houston Symphony Third Annual Commission Club with composer Mark Adamo to support the creation of Last Year ACO Gala 2020 honoring Anthony Roth Constanzo, Jesse Rosen, & Yolanda Wyns March 4, 2020 at Bryant Park Grill www.americancomposers.org New York, NY – American Composers Orchestra (ACO) announces its full 2019-2020 season of performances and engagements, under the leadership of Artistic Director Derek Bermel, Music Director George Manahan, and President Edward Yim. ACO continues its commitment to the creation, performance, preservation, and promotion of music by 1 American Composers Orchestra – 2019-2020 Season Overview American composers with programming that sparks curiosity and reflects geographic, stylistic, racial and gender diversity. ACO’s concerts at Carnegie Hall on November 13, 2019 and April 2, 2020 include major premieres by 2015 Rome Prize winner Mark Adamo, 2014 Pulitzer Prize winner John Luther Adams, 2018 MacArthur Fellow Matthew Aucoin, 2017 ACO Underwood Commission winner Hilary Purrington, and 2013 ACO Underwood Audience Choice Award winner Nina C. -

A Scene Without a Name: Indie Classical and American New Music in the Twenty-First Century

A SCENE WITHOUT A NAME: INDIE CLASSICAL AND AMERICAN NEW MUSIC IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY William Robin A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Mark Katz Andrea Bohlman Mark Evan Bonds Tim Carter Benjamin Piekut © 2016 William Robin ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT WILLIAM ROBIN: A Scene Without a Name: Indie Classical and American New Music in the Twenty-First Century (Under the direction of Mark Katz) This dissertation represents the first study of indie classical, a significant subset of new music in the twenty-first century United States. The definition of “indie classical” has been a point of controversy among musicians: I thus examine the phrase in its multiplicity, providing a framework to understand its many meanings and practices. Indie classical offers a lens through which to study the social: the web of relations through which new music is structured, comprised in a heterogeneous array of actors, from composers and performers to journalists and publicists to blog posts and music venues. This study reveals the mechanisms through which a musical movement establishes itself in American cultural life; demonstrates how intermediaries such as performers, administrators, critics, and publicists fundamentally shape artistic discourses; and offers a model for analyzing institutional identity and understanding the essential role of institutions in new music. Three chapters each consider indie classical through a different set of practices: as a young generation of musicians that constructed itself in shared institutional backgrounds and performative acts of grouping; as an identity for New Amsterdam Records that powerfully shaped the record label’s music and its dissemination; and as a collaboration between the ensemble yMusic and Duke University that sheds light on the twenty-first century status of the new-music ensemble and the composition PhD program. -

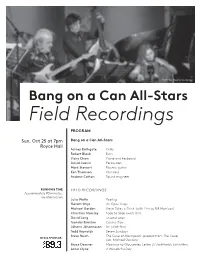

Field Recordings

Photo by Stephanie Berger Bang on a Can All-Stars Field Recordings PROGRAM Sun, Oct 25 at 7pm Bang on a Can All-Stars Royce Hall Ashley Bathgate Cello Robert Black Bass Vicky Chow Piano and keyboard David Cossin Percussion Mark Stewart Electric guitar Ken Thomson Clarinets Andrew Cotton Sound engineer RUNNING TIME FIELD RECORDINGS Approximately 90 minutes; no intermission Julia Wolfe Reeling Florent Ghys An Open Cage Michael Gordon Gene Takes a Drink (with film by Bill Morrison) Christian Marclay Fade to Slide (with film) David Lang unused swan Tyondai Braxton Casino Trem Jóhann Jóhannsson Hz (with film) Todd Reynolds Seven Sundays Steve Reich The Cave of Machpelah (excerpt from The Cave) MEDIA SPONSOR: (arr. Michael Gordon) Bryce Dessner Maximus to Gloucester, Letter 27 [withheld] (with film) Anna Clyne A Wonderful Day PROGRAM NOTES MESSAGE FROM THE CENTER: For 135 years recorded sound has permeated every corner of our For almost 25 years, the phrase Bang On A Can All-Stars lives, changing music along with everything else. Bartok and Kodaly has been synonymous with innovation in the world of took recording devices into the hills of central Europe and modern contemporary music. While the performer lineup may music was never the same; rock and roll’s lineage comes from change periodically, the symbiotic relationship between artists revealed to the world by the Lomaxes, the Seegers, and other musicians and modern composers remains staunchly and archivists. Hip-hop culture democratized sampling: popular music illuminatingly in place. today is a form of musique concrète, the voices & rhythms of the past mixing with the sound of machinery and electronics. -

Istanbul Technical University Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences Masters Thesis June 2019 Spatialization Through Ge

ISTANBUL TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES SPATIALIZATION THROUGH GEOMETRICAL SOUND MOVEMENTS IN PERSEPHASSA BY IANNIS XENAKIS MASTERS THESIS Sabina KHUJAEVA Institute of Social Sciences Masters Programme in Music JUNE 2019 ISTANBUL TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ART AND SOCIAL SCIENCES SPATIALIZATION THROUGH GEOMETRICAL SOUND MOVEMENTS IN PERSEPHASSA BY IANNIS XENAKIS M.A. THESIS Sabina KHUJAEVA (409151116) Institute of Social Sciences Masters Programme in Music Thesis Advisor: Assist. Prof. Dr. Eray ALTINBÜKEN JUNE 2019 ISTANBUL TEKNİK ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLERİ ENSTİTÜSÜ IANNIS XENAKIS'İN PERSEPHASSA ESERİNDE GEOMETRİK SES HAREKETLERİ ARACILIĞIYLA MEKANSALLAŞTIRMA YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ Sabina KHUJAEVA (409151116) Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Müzik Yüksek Lisans Programı Tez Danışmanı: Dr. Öğ. Üyesi Eray ALTINBÜKEN HAZİRAN 2019 Sabina KHUJAEVA, an M.A.student of İTU Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences, 40915116, successfully defended the thesis entitled “SPATIALIZATION THROUGH GEOMETRICAL SOUND MOVEMENTS IN PERSEPHASSA BY IANNIS XENAKIS”, which she prepared after fulfilling the requirements specified in the associated legislations before the jury whose signatures are below. Thesis Advisor : Assist. Prof. Dr. Eray ALTINBÜKEN .............................. İstanbul Technical University Jury Members : Prof. Dr. Tolga TÜZÜN ............................. Istanbul Bilgi University Assoc. Prof. Dr. Jerfi AJİ .............................. İstanbul Technical University Date of Submission : 3 May 2019 Date of Defense : 10 June 2019 v vi To my mother, vii viii FOREWORD This project has been developed out of ideas that emerged in courses and case studies I attended during my master studies at MIAM for the past three years. It would not have had the spirit without the invaluable influence, active contribution, support and psychological help of very unique people to whom I would like to express my deep feelings of gratitude. -

Woodblock (Instrument)

Woodblock (instrument) A wood block (also spelled as a single word, woodblock) is a small slit Woodblock drum made from a single piece of wood and used as a percussion instrument. The term generally signifies the Western orchestral instrument, though it is related to the ban time-beaters used by the Han Chinese, which is why the Western instrument is sometimes referred to as Chinese woodblock. Alternative names sometimes used in ragtime and jazz are clog box and tap box. In orchestral music scores, wood blocks may be indicated by the French bloc de bois or tambour de bois, German Holzblock or Holzblocktrommel, or Italian cassa di legno (Blades and Holland 2001). Percussion instrument The orchestral wood block of the West is generally made from teak or Other names Woodblock, another hardwood. The dimensions of this instrument vary, although it is Chinese either a rectangular or cylindrical block of wood with one or sometimes woodblock, Clog two longitudinal cavities (Blades and Holland 2001). It is played by box, Tap box striking it with a stick, which produces a sharp crack (Montagu 2002b). Classification Percussion Alternatively, a rounder mallet, soft or hard, may be used, which produces Hornbostel 111.2 a deeper-pitched and fuller "knocking" sound. –Sachs (Percussion In a drum kit, a wood block was traditionally mounted on a clamp fixed to classification idiophones) the top of the rear rim of the bass drum. Related instruments slit drum, temple blocks, log drums, Related instruments muyu, jam block, simantra Log drums made from hollowed logs, and slit drums made from bamboo, are used in Africa and the Pacific Islands.