Evolution of Track and Field Rules During the Last Century by Eric D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HHSAA Track & Field Handbook

TRACK AND FIELD I. SPECIFIC OBJECTIVES A. To determine the state boys and girls individual and team champions. B. To bring schools within leagues in the state together to: 1. Foster friendly competition between them, and 2. Enhance the quality of high school track and field in the state. C. To promote citizenship on the part of individuals, teams, schools and spectators. II. OFFICIALS A. Volunteers and officials shall be selected and assigned by the HHSAA Executive Director, Sport Coordinator and Tournament Director. B. As provided for in the rule book, a Board of Appeals will be named to assist the Meet Referee. Appeals on officials’ decisions to this committee must be made through the Meet Director. III. ELIGIBILITY See HHSAA Handbook. IV. GAMES COMMITTEE The HHSAA shall form a Games Committee as called for by the National Federation. The committee should be composed of at least one representative from each league. It should meet to settle issues prior to the start of the track and field season. The committee is responsible for the proper conduct of track and field meet. Other responsibilities are listed under National Federation Rule 3, Section 2, Articles 1‐4. V. RULES GOVERNING THE TOURNAMENT A. The National Federation Track and Field Rules will govern, with the following HHSAA modifications: 1. Have the girls go first in all running events for both trials and finals. The order of field events shall be as follows: Discus – boys first, girls to follow; Shot Put – boys first, girls to follow; Long Jump – boys first, girls to follow; Triple Jump – boys first, girls to follow. -

Athletics (Track & Field) 2015 General Rules

ATHLETICS (TRACK & FIELD) 2015 GENERAL RULES The Official Special Olympics Sports Rules shall govern all Special Olympics athletics competitions. As an international sports program, Special Olympics has created these rules based upon Internationale Amateur Athletic Federation (IAAF) and National Governing Body (NGB) rules for athletics. IAAF or National Governing Body rules shall be employed except when they are in conflict with the Official Special Olympics Sports Rules. For more information, visit www.iaaf.org. DEVELOPMENTAL EVENTS 1. Assisted Run (regional level only, non-advancing) 2. 50m Run* 3. 25m Walk* 4. Standing Long Jump* 5. Softball Throw* (Athletes throwing over 15m should compete in the shot put or mini jav; athletes who have thrown more than 20m in a SOWI competition will be ineligible to participate in softball throw following that season.) 6. 25m Non-Motorized Wheelchair* 7. 30m Non-Motorized Wheelchair Slalom* 8. 30 and 50m Motor Wheelchair Slalom* 9. 25m Motor Wheelchair Obstacle Course* 10. 4x25m Non-Motorized Wheelchair Shuttle Relay* *These events with an asterisk are considered developmental events and provide meaningful competition for athletes with lower ability levels and are not meant to be paired with other events (except field events) when entering athletes in competition. OFFICIAL EVENTS OFFERED 1. 100, 200, 400, 800, 1500, 3000m Run 8. 4x100m Relay 2. 100, 200, 400*, 800*, 1500m* Walk 9. 4x200 m Relay 3. High Jump – no longer offered as an event 10. 4x400m Relay 4. Long Jump 11. Pentathalon – no longer offered as an event 5. Shot Put 12. 100, 200m Non-Motorized Wheelchair 6. Mini Jav (formerly known as Turbo Jav) 13. -

Shoes Approved by World Athletics - As at 01 October 2021

Shoes Approved by World Athletics - as at 01 October 2021 1. This list is primarily a list concerns shoes that which have been assessed by World Athletics to date. 2. The assessment and whether a shoe is approved or not is determined by several different factors as set out in Technical Rule 5. 3. The list is not a complete list of every shoe that has ever been worn by an athlete. If a shoe is not on the list, it can be because a manufacturer has failed to submit the shoe, it has not been approved or is an old model / shoe. Any shoe from before 1 January 2016 is deemed to meet the technical requirements of Technical Rule 5 and does not need to be approved unless requested This deemed approval does not prejudice the rights of World Athletics or Referees set out in the Rules and Regulations. 4. Any shoe in the list highlighted in blue is a development shoe to be worn only by specific athletes at specific competitions within the period stated. NON-SPIKE SHOES Shoe Company Model Track up to 800m* Track from 800m HJ, PV, LJ, SP, DT, HT, JT TJ Road* Cross-C Development Shoe *not including 800m *incl. track RW start date end date ≤ 20mm ≤ 25mm ≤ 20mm ≤ 25mm ≤ 40mm ≤ 25mm 361 Degrees Flame NO NO NO NOYES NO Adidas Adizero Adios 3 NO YES NO YES YES YES Adidas Adizero Adios 4 NO YES NO YES YES YES Adidas Adizero Adios 5 NO YES NO YES YES YES Adidas Adizero Adios 6 NO YES NO YES YES YES Adidas Adizero Adios Pro NO NO NO NOYES NO Adidas Adizero Adios Pro 2 NO NO NO NOYES NO Adidas Adizero Boston 8 NO NO NO NOYES NO Adidas Adizero Boston 9 NO NO NO -

1994 Press Release

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Women's Track and Field George Fox University Athletics 1994 1994 Press Release George Fox University Archives Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/athletics_womentrack Recommended Citation George Fox University Archives, "1994 Press Release" (1994). Women's Track and Field. 6. https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/athletics_womentrack/6 This Press Release is brought to you for free and open access by the George Fox University Athletics at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Women's Track and Field by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ~SPORTS NEWS---- GEORGE FOX COLLEGE SPORTS INFORMATION OFFICE NEW BERG. OREGON 97 132-2697 503 I 538-8383. EXT. 292 FAX 503 I 537-3830 May 31, 1994 Contact: Rob Felton Sports Information Director GEORGE FOX COLLEGE TRACK AND FIELD GFC TRACK TEAMS TAKE TOP-25 FINISHES AT NATIONAL MEET George Fox College' s young 13-member squad of athletes gave solid efforts and showed potential for the future last weekend (May 26-28) at the NAIA national track and field championships in Azusa, Calif. Four GFC women scored points -two wi th All-American efforts -propelling the Lady Bruins to a 21st-place finish, and the men tied for 25th without any help from upperclassmen. Two of the three Bruin men at the meet earned All-American honors (for top six finishes) and the other narrowly missed the finals. Juli Cyrus (Sr., Newberg, Ore.) polished off her collegiate career with a fourth-place finish in the 3,000 meters. -

Success on the World Stage Athletics Australia Annual Report 2010–2011 Contents

Success on the World Stage Athletics Australia Annual Report Success on the World Stage Athletics Australia 2010–2011 2010–2011 Annual Report Contents From the President 4 From the Chief Executive Officers 6 From The Australian Sports Commission 8 High Performance 10 High Performance Pathways Program 14 Competitions 16 Marketing and Communications 18 Coach Development 22 Running Australia 26 Life Governors/Members and Merit Award Holders 27 Australian Honours List 35 Vale 36 Registration & Participation 38 Australian Records 40 Australian Medalists 41 Athletics ACT 44 Athletics New South Wales 46 Athletics Northern Territory 48 Queensland Athletics 50 Athletics South Australia 52 Athletics Tasmania 54 Athletics Victoria 56 Athletics Western Australia 58 Australian Olympic Committee 60 Australian Paralympic Committee 62 Financial Report 64 Chief Financial Officer’s Report 66 Directors’ Report 72 Auditors Independence Declaration 76 Income Statement 77 Statement of Comprehensive Income 78 Statement of Financial Position 79 Statement of Changes in Equity 80 Cash Flow Statement 81 Notes to the Financial Statements 82 Directors’ Declaration 103 Independent Audit Report 104 Trust Funds 107 Staff 108 Commissions and Committees 109 2 ATHLETICS AuSTRALIA ANNuAL Report 2010 –2011 | SuCCESS ON THE WORLD STAGE 3 From the President Chief Executive Dallas O’Brien now has his field in our region. The leadership and skillful feet well and truly beneath the desk and I management provided by Geoff and Yvonne congratulate him on his continued effort to along with the Oceania Council ensures a vast learn the many and numerous functions of his array of Athletics programs can be enjoyed by position with skill, patience and competence. -

Lesson Plans Introduction the Following Section Provides Twenty-Seven Ready-To-Implement Lesson Plans for Teachers

Lesson Plans Introduction The following section provides twenty-seven ready-to-implement lesson plans for teachers. The section is divided into four smaller sub-sections. • Early Stage 1 (5 year olds) • Stage 1 (6/7 year olds) • Stage 2 (8/9 year olds) • Stage 3 (10 years and LAANSWabove) ASAP Level 3 Each sub-section contains lesson plans suitable for children in these age groups. The lesson plans assume classes of up to thirty students and a time limit of 30-45 minutes, however a teacher can adapt the ideas to suit their particular circumstances. Each lesson plan generally follows the same format, being: Aim; Equipment; Warm Up; Skill Development; Games. In relevant places, topics such as safety aspects and various hints that will help the teacher organise and conduct a successful lesson are included. The lesson plans at times assume prior learning, ie. that the children have participated in the skill development activities contained in preceding lessons designed for the earlier levels. The activities featured in the lesson plans are based on fun, skill development, maximum group participation and a sound, logical progression. The lesson plans form the foundation of a class athletics unit. 3 29 Early Stage 1 Lesson Plans • Running - Lesson 1 - Lesson 2 • Jumping - Lesson 1 - LessonLAANSW 2 ASAP Level 3 • Throwing - Lesson 1 - Lesson 2 30 Early Stage 1 Running Lesson Plan Lesson 1 Introduction to basic running technique Introduction to relays Ground markers x 30 Relay batons x 5 Warm Up 1. Group Game: "Signals" LAANSW ASAP Level 3 Set up a playing area with ground markers. -

Runners in Their Forties Dominate Ultra-Marathons from 50 to 3,100 Miles

CLINICAL SCIENCE Runners in their forties dominate ultra-marathons from 50 to 3,100 miles Matthias Alexander Zingg,I Christoph Alexander Ru¨ st,I Thomas Rosemann,I Romuald Lepers,II Beat KnechtleIII I University of Zurich, Institute of General Practice and for Health Services Research, Zurich, Switzerland. II University of Burgundy, Faculty of Sport Sciences, INSERM U1093, Dijon, France. III Gesundheitszentrum St. Gallen, St. Gallen, Switzerland. OBJECTIVES: This study investigated performance trends and the age of peak running speed in ultra-marathons from 50 to 3,100 miles. METHODS: The running speed and age of the fastest competitors in 50-, 100-, 200-, 1,000- and 3,100-mile events held worldwide from 1971 to 2012 were analyzed using single- and multi-level regression analyses. RESULTS: The number of events and competitors increased exponentially in 50- and 100-mile events. For the annual fastest runners, women improved in 50-mile events, but not men. In 100-mile events, both women and men improved their performance. In 1,000-mile events, men became slower. For the annual top ten runners, women improved in 50- and 100-mile events, whereas the performance of men remained unchanged in 50- and 3,100-mile events but improved in 100-mile events. The age of the annual fastest runners was approximately 35 years for both women and men in 50-mile events and approximately 35 years for women in 100-mile events. For men, the age of the annual fastest runners in 100-mile events was higher at 38 years. For the annual fastest runners of 1,000-mile events, the women were approximately 43 years of age, whereas for men, the age increased to 48 years of age. -

Athletics, Badminton, Gymnastics, Judo, Swimming, Table Tennis, and Wrestling

INDIVIDUAL GAMES 4 Games and sports are important parts of our lives. They are essential to enjoy overall health and well-being. Sports and games offer numerous advantages and are thus highly recommended for everyone irrespective of their age. Sports with individualistic approach characterised with graceful skills of players are individual sports. Do you like the idea of playing an individual sport and be responsible for your win or loss, success or failure? There are various sports that come under this category. This chapter will help you to enhance your knowledge about Athletics, Badminton, Gymnastics, Judo, Swimming, Table Tennis, and Wrestling. ATHLETICS Running, jumping and throwing are natural and universal forms of human physical expression. Track and field events are the improved versions of all these. These are among the oldest of all sporting competitions. Athletics consist of track and field events. In the track events, competitions of races of different distances are conducted. The different track and field events have their roots in ancient human history. History Ancient Olympic Games are the first recorded examples of organised track and field events. In 776 B.C., in Olympia, Greece, only one event was contested which was known as the stadion footrace. The scope of the games expanded in later years. Further it included running competitions, but the introduction of the Ancient Olympic pentathlon marked a step towards track and field as it is recognised today. There were five events in pentathlon namely—discus throw, long jump, javelin throw, the stadion foot race, and wrestling. 2021-22 Chap-4.indd 49 31-07-2020 15:26:11 50 Health and Physical Education - XI Track and field events were also present at the Pan- Activity 4.1 Athletics at the 1960 Summer Hellenic Games in Greece around 200 B.C. -

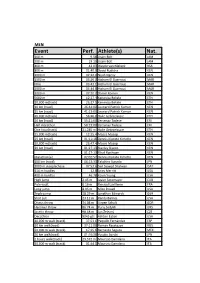

Event Perf. Athlete(S) Nat

MEN Event Perf. Athlete(s) Nat. 100 m 9.58 Usain Bolt JAM 200 m 19.19 Usain Bolt JAM 400 m 43.03 Wayde van Niekerk RSA 800 m 01:40.9 David Rudisha KEN 1000 m 02:12.0 Noah Ngeny KEN 1500 m 03:26.0 Hicham El Guerrouj MAR Mile 03:43.1 Hicham El Guerrouj MAR 2000 m 04:44.8 Hicham El Guerrouj MAR 3000 m 07:20.7 Daniel Komen KEN 5000 m 12:37.4 Kenenisa Bekele ETH 10,000 m(track) 26:17.5 Kenenisa Bekele ETH 10 km (road) 26:44:00 Leonard Patrick Komon KEN 15 km (road) 41:13:00 Leonard Patrick Komon KEN 20,000 m(track) 56:26.0 Haile Gebrselassie ETH 20 km (road) 55:21:00 Zersenay Tadese ERI Half marathon 58:23:00 Zersenay Tadese ERI One hour(track) 21,285 m Haile Gebrselassie ETH 25,000 m(track) 12:25.4 Moses Mosop KEN 25 km (road) 01:11:18 Dennis Kipruto Kimetto KEN 30,000 m(track) 26:47.4 Moses Mosop KEN 30 km (road) 01:27:13 Stanley Biwott KEN 01:27:13 Eliud Kipchoge KEN Marathon[a] 02:02:57 Dennis Kipruto Kimetto KEN 100 km (road) 06:13:33 Takahiro Sunada JPN 3000 m steeplechase 07:53.6 Saif Saaeed Shaheen QAT 110 m hurdles 12.8 Aries Merritt USA 400 m hurdles 46.78 Kevin Young USA High jump 2.45 m Javier Sotomayor CUB Pole vault 6.16 m Renaud Lavillenie FRA Long jump 8.95 m Mike Powell USA Triple jump 18.29 m Jonathan Edwards GBR Shot put 23.12 m Randy Barnes USA Discus throw 74.08 m Jürgen Schult GDR Hammer throw 86.74 m Yuriy Sedykh URS Javelin throw 98.48 m Jan Železný CZE Decathlon 9045 pts Ashton Eaton USA 10,000 m walk (track) 37:53.1 Paquillo Fernández ESP 10 km walk(road) 37:11:00 Roman Rasskazov RUS 20,000 m walk (track) 17:25.6 Bernardo -

Track and Field Skills — Striding, Hurdling, Hop, Step, and Jump

GRADES 5-8 LESSON FOCUS Track and Field Skills — Striding, Hurdling, Hop, Step, and Jump SHAPE Standards: DPE Outcomes: Equipment: 4 • I can listen to and use feedback provided by • High jump equipment my peer. • Batons • I can provide appropriate performance feedback • Stopwatches to my peers. • Tape measures • I can compliment classmates on their • Hurdles Instructions performance during physical education. Skills Introduce the following skills before proceeding to small group instruction. Striding In distance running, as compared with sprinting, the body is more erect and the motion of the arms is less pronounced. Pace is an important consideration. Runners should try to concentrate on the qualities of lightness, ease, relaxation, and looseness. Good striding action, a slight body lean, and good head position are also important. Runners should be encouraged to strike the ground with the heel first and then push off with the toes. Hurdling Several key points govern good hurdling technique. The runner should adjust his stepping pattern so that the takeoff foot is planted 3 to 5 feet from the hurdle. The lead foot is extended straight forward over the hurdle; the rear (trailing) leg is bent, with the knee to the side. The lead foot reaches for the ground, quickly followed by the trailing leg. The hurdler should avoid floating over the hurdle. Body lean is necessary. A hurdler may lead with the same foot over consecutive hurdles or may alternate the leading foot. Some hurdlers like to thrust both arms forward instead of a single arm. A consistent step pattern should be developed. Wands supported on blocks or cones can also be used as hurdles. -

Millersvillewomen's Indoor Track

MILLERSVILLE WOMEN’S INDOOR TRACK & FIELD RECORDS PSAC INDOOR CHAMPIONSHIPS All-PSAC Indoor (PSAC officially recognized top three as All-PSAC in 2001) Year Athlete Event Place Time/Distance 2001-02 Beth Lord Weight Throw 1st 2019-20 Aliyah Striver Shot Put 1st 44-5 1/4 Theresa Mazurek Mile 2nd Aliyah Striver Weight Throw 1st 54-2 3/4 Christina Carpenter 55-Meter Dash 3rd Madison Martin Weight Throw 2nd 54-2 1/4 200-Meter Dash 3rd De’Asia Holloman 60-Meter Hurdles 2nd 8.91 --- 4 x 800M Relay 2nd 2002-03 Juleann Benkoski High Jump 2nd PSAC Indoor Championships Finishes Theresa Mazurek Mile 3rd Year Place Points # of Teams 2003-04 Christina Carpenter 55-Meter Dash 2nd 2002 5th 53.6 10 200-Meter Dash 2nd 2003 8th 22 12 Beth Lord Weight Throw 3rd 2004 6th 34 12 Juleann Benkoski High Jump T-3rd 2005 10th 17.33 12 2004-05 Christina Carpenter 200-Meter Dash 2nd 2006 12th 11 13 2007 6th 51 14 2005-06 Priscilla Jennings 800 Meters 3rd 2:20.99 2008 6th 63 12 2006-07 Priscilla Jennings 800 Meters 1st 2:17.46 2009 7th 39 12 Priscilla Jennings Mile 2nd 5:04.02 2010 14th 4 14 4x800-Meter Relay 2nd 9:30.59 2011 8th 38 14 2007-08 Priscilla Jennings Mile 1st 5:03.27 2012 10th 35 14 Priscilla Jennings 800 Meters 2nd 2:14.32 2013 10th 27 13 -- Distance Medley Relay 1st 12:04.08 2014 6th 47 14 2015 8th 33 16 2008-09 Priscilla Jennings 800 Meters 2nd 2:14.76 2016 6th 40 16 Priscilla Jennings Mile 2nd 4:54.90 2017 12th 18 15 -- Distance Medley Relay 3rd 11:55.55 2018 7th 51 16 Michele Frayne Pentathlon 2nd 3,402 points 2019 5th 60 14 2010-11 Elicia Anderson -

HEEL and TOE ONLINE the Official Organ of the Victorian Race Walking

HEEL AND TOE ONLINE The official organ of the Victorian Race Walking Club 2019/2020 Number 40 Tuesday 30 June 2020 VRWC Preferred Supplier of Shoes, clothes and sporting accessories. Address: RUNNERS WORLD, 598 High Street, East Kew, Victoria (Melways 45 G4) Telephone: 03 9817 3503 Hours: Monday to Friday: 9:30am to 5:30pm Saturday: 9:00am to 3:00pm Website: http://www.runnersworld.com.au Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/pages/Runners-World/235649459888840 VRWC COMPETITION RESTARTS THIS SATURDAY Here is the big news we have all been waiting for. Our VRWC winter roadwalking season will commence on Saturday afternoon at Middle Park. Club Secretary Terry Swan advises the the club committee meet tonight (Tuesday) and has given the green light. There will be 3 Open races as follows VRWC Roadraces, Middle Park, Saturday 6th July 1:45pm 1km Roadwalk Open (no timelimit) 2.00pm 3km Roadwalk Open (no timelimit) 2.30pm 10km Roadwalk Open (timelimit 70 minutes) Each race will be capped at 20 walkers. Places will be allocated in order of entry. No exceptions can be made for late entries. $10 per race entry. Walkers can only walk in ONE race. Multiple race entries are not possible. Race entries close at 6PM Thursday. No entries will be allowed on the day. You can enter in one of two ways • Online entry via the VRWC web portal at http://vrwc.org.au/wp1/race-entries-2/race-entry-sat-04jul20/. We prefer payment by Credit Card or Paypal within the portal when you register. Ignore the fact that the portal says entries close at 10PM on Wednesday.