Exploring Queer Conservatism Austin P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Political Participation in France Among Non-European-Origin Migrants: Segregation Or Integration? Rahsaan Maxwell a a University of Massachusetts, Amherst

This article was downloaded by: [Maxwell, Rahsaan] On: 13 February 2010 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 919249752] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37- 41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713433350 Political Participation in France among Non-European-Origin Migrants: Segregation or Integration? Rahsaan Maxwell a a University of Massachusetts, Amherst First published on: 17 December 2009 To cite this Article Maxwell, Rahsaan(2010) 'Political Participation in France among Non-European-Origin Migrants: Segregation or Integration?', Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 36: 3, 425 — 443, First published on: 17 December 2009 (iFirst) To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/13691830903471537 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13691830903471537 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

The Changing Face of American White Supremacy Our Mission: to Stop the Defamation of the Jewish People and to Secure Justice and Fair Treatment for All

A report from the Center on Extremism 09 18 New Hate and Old: The Changing Face of American White Supremacy Our Mission: To stop the defamation of the Jewish people and to secure justice and fair treatment for all. ABOUT T H E CENTER ON EXTREMISM The ADL Center on Extremism (COE) is one of the world’s foremost authorities ADL (Anti-Defamation on extremism, terrorism, anti-Semitism and all forms of hate. For decades, League) fights anti-Semitism COE’s staff of seasoned investigators, analysts and researchers have tracked and promotes justice for all. extremist activity and hate in the U.S. and abroad – online and on the ground. The staff, which represent a combined total of substantially more than 100 Join ADL to give a voice to years of experience in this arena, routinely assist law enforcement with those without one and to extremist-related investigations, provide tech companies with critical data protect our civil rights. and expertise, and respond to wide-ranging media requests. Learn more: adl.org As ADL’s research and investigative arm, COE is a clearinghouse of real-time information about extremism and hate of all types. COE staff regularly serve as expert witnesses, provide congressional testimony and speak to national and international conference audiences about the threats posed by extremism and anti-Semitism. You can find the full complement of COE’s research and publications at ADL.org. Cover: White supremacists exchange insults with counter-protesters as they attempt to guard the entrance to Emancipation Park during the ‘Unite the Right’ rally August 12, 2017 in Charlottesville, Virginia. -

Border War Intel Find out What Wyo

You’re paying student government $35.92 per semester. Did they serve you this week? | Page 5 PAGE 6 Border War Intel Find out what Wyo. thinks of this year’s battle for the Bronze Boot THE ROCKY MOUNTAIN Fort Collins, Colorado Volume 121 | No. 62 ursday, November 1, 2012 COLLEGIAN www.collegian.com THE STUDENT VOICE OF COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY SINCE 1891 the STRIP Halloween Heroes CLUB With the predicted end of the world nearly upon us (12/21/12), it is time to start focusing our attention on ways in which the world will end. is week: the technologi- cal apocalypse of the Robot Uprising (already in progress). Ways in Which Robots will Rule the World LEFT: Haruto Yoshikawa chases his big brother while donning his Superman halloween costume on the west lawn Wednesday evening. Yoshikawa is a refreshing reminder of why homeowners give out candy to young kids and not college students. (Photo by Hunter Thompson) RIGHT: A lone shark looks on as a group of Atheists and Christians duke it out on the plaza this Wednesday. As the two groups shout out declaring their opinion is right, the shark believes that both groups look tasty. (Photo by Kevin Johansen) Cars We already rely “Most of my friends are party a liated and will vote for the ticket rather than vote on robots when it comes to car for the candidate and I just think that’s studpid.” manufacturing. Chris Lopina | senior journalism major ey assemble chassis and weld various parts together. Soon, cars Meet the Undecided themselves will not only Some students still unsure of vote choice with less than a week remaining be capable of self-navigation, By KATE WINKLE cording to Davis. -

Alumni Reserve Yiannopoulos Tickets, Leave Ha) F of Seats Empty in Protest

oo© © u d re v ie w T he R eview TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 1, 2016 VOLUME 142, ISSUE 9 The University of Delaware's independent student newspaper since 1882 | udreview.com President Assanis talks “evolving” future of the university Homecoming and Halloween JOHN RYAN BARWICK role is to lead the charge, and set weekend kept & MICHAE l T. HENRETTY JR. the vision to move the university Executive Editor to the next level. I find this [to be] & Managing News Editor a great responsibility." university Previously the provost President Dennis Assanis' at Stony Brook University, morning begins around six, Assanis worked for 17 years with a cup of coffee and a at the University of Michigan, police busy review of the emails sent to him serving in several positions. overnight. Next, he exercises Assanis holds four degrees from before responding to his mail the Massachusetts Institute and preparing for his morning’s of Technology and one from meetings. He then heads to his SEASON COOPER Newcastle University in England. office, working until midnight. Senior Reporter Born in Greece, as evidenced With typically less than by his accent, Assanis was the 20 percent of his time spent This weekend, which first member of his family to in the office, most of Assanis’ included both Homecoming and attend college. His father was a day involves him moving from Halloween celebrations, saw an sea captain for 23 years, taking meeting to meeting, making increase in arrests for underage Assanis with him as a young boy announcements and policy consumption. Last year there for voyages stretching up to 23 proposals and attending were 11 reports of underage days at a time. -

College Voice Vol. XLI No. 6

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College 2017-2018 Student Newspapers 12-5-2017 College Voice Vol. XLI No. 6 Connecticut College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/ccnews_2017_2018 Recommended Citation Connecticut College, "College Voice Vol. XLI No. 6" (2017). 2017-2018. 5. https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/ccnews_2017_2018/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspapers at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2017-2018 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. NEW LONDON, CONNECTICUT TUESDAY, DECEMBER 5, 2017 VOLUME XLI • ISSUE 6 THE COLLEGE VOICE CONNECTICUT COLLEGE’S INDEPENDENT STUDENT NEWSPAPER SINCE 1977 Shelter Proves Net Neutrality Crucial in Opioid Under Grave Threat Epidemic Baretta Lauren of courtesy Photo ABIGAIL ACHESON CAMERON DYER-HAWES STAFF WRITER CONTRIBUTOR No matter how snugly it sits in Deaths from opioid overdoses the pocket of corporations, the fed- have quadrupled since 1999. The eral government is still responsible National Institute on Drug Abuse for protecting citizens from the estimates that over 64,000 Ameri- type of unashamed indecency of cans died from a drug overdose in expected exploits that would come 2016 alone, and almost half (46%) with the repeal of net neutrality. of the American population has a The Obama-era regulation ensures family member or close friend with that internet providers are not al- a current or past drug addiction lowed to create tiered access to the web. -

Beyond the Bully Pulpit: Presidential Speech in the Courts

SHAW.TOPRINTER (DO NOT DELETE) 11/15/2017 3:32 AM Beyond the Bully Pulpit: Presidential Speech in the Courts Katherine Shaw* Abstract The President’s words play a unique role in American public life. No other figure speaks with the reach, range, or authority of the President. The President speaks to the entire population, about the full range of domestic and international issues we collectively confront, and on behalf of the country to the rest of the world. Speech is also a key tool of presidential governance: For at least a century, Presidents have used the bully pulpit to augment their existing constitutional and statutory authorities. But what sort of impact, if any, should presidential speech have in court, if that speech is plausibly related to the subject matter of a pending case? Curiously, neither judges nor scholars have grappled with that question in any sustained way, though citations to presidential speech appear with some frequency in judicial opinions. Some of the time, these citations are no more than passing references. Other times, presidential statements play a significant role in judicial assessments of the meaning, lawfulness, or constitutionality of either legislation or executive action. This Article is the first systematic examination of presidential speech in the courts. Drawing on a number of cases in both the Supreme Court and the lower federal courts, I first identify the primary modes of judicial reliance on presidential speech. I next ask what light the law of evidence, principles of deference, and internal executive branch dynamics can shed on judicial treatment of presidential speech. -

View Full Issue As

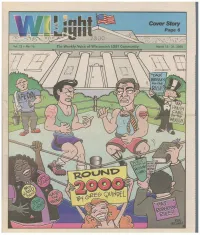

Cover Story Page 6 ,-; - ">>(C Vol. 13 • No. 16 The Weekly Voice of Wisconsin's LGBT Community March 15 - 21, 2000 // \\\ f /%7 C HEALTH CARE • forfhe to 4 AP. NVKE WHALE&AY R oot417 • %at I 25,1 &czE(7 QuirloEt .40 41 WI LIAM5 A\ www.wngnt.tom VOLUNTEER TODAY And Change Your World Comedienne Suzanne Wegtenhoefet Wanna' Start Saturday, March 25 • 8pm Some Doors Open at 7pm moon Then why not volunteer at I til/44 I I 111011 your local neighborhood LGBT Community Center? 2090 Atwood Ave • Madison • Answer the LCBT info line $17.50 Advance / $19.50 Door • Start a program • Help raise funds with special guest • Expand our library. • Support youth leadership ZRZYA tit* Milwaukee Smooth as silk, Dublin, Ireland - V V V based world-jazz funksters . v V V I,GBT - Time Out (London) Commtutity Center BUY YOUR TICKETS AT: The Barrymore Box Office Exclusive Company (State & High Point) 170 South 2nd. Street Magic Mill • A Room of One's Own "Wickedly righteous . 414-271-2656 Star Liquor • Green Earth www.mkelght.org a riotous look at life." OR CHARGE BY PHONE: (608) 241-8633 - San Diego Gay & Lesbian Times Make Them BODY INSPIRED With Envy MILWAUKEE'S EAST SIDE HEALTH CLUB TANNING & MASSAGE 272.8622 2009 E. Kenilworth Place (2 blocks south of North Ave.) www.wilight.com News &Politics March 15 - 21, 2000 Wight 3 and sentence, however, because of over- employment matters. whelming evidence that Burdine's defense All 28 Republican Senators voted to nullify National lawyer slept through much of the trial. -

1 Chairman Reince Priebus C/O Republican National Committee

Chairman Reince Priebus C/O Republican National Committee 310 First Street, SE Washington, DC 20003 April 8, 2013 Dear Chairman Priebus, We write to express our great displeasure with the RNC commissioned report titled Growth and Opportunity Project. As individuals and organizations which represent millions of grassroots, faith-based voters who have supported (politically and financially) thousands of Republican candidates who share our values, we write to say: The Republican Party makes a huge historical mistake if it intends to dismantle this coalition by marginalizing social conservatives and avoiding the issues which attract and energize them by the millions. Unfortunately, the report dismisses the Reagan Coalition as a political relic of the past. It’s important to remember that from 1932-1980, the Republican Party was a permanent minority party. Political debate was confined to economic issues like the expansion of the Federal Government, taxes, and national security. It was not until 1980 with key changes in the GOP Platform and the nomination of Ronald Reagan that social conservatives were clearly invited to be an important addition to this coalition. Millions of “Reagan Democrats” voted not only for President Ronald Reagan, but became active in supporting other GOP candidates who shared their faith-based family values. That’s how Republicans achieved many successes since 1980 at every level of government. The report states on page seven that “America looks different.” It certainly does, but here are some facts about minority outreach…not opinions and theories from DC Consultants: 1 1. In 2004, President Bush carried Ohio because of the outreach to African-American pastors supporting a traditional marriage amendment on the ballot. -

The Radical Roots of the Alt-Right

Gale Primary Sources Start at the source. The Radical Roots of the Alt-Right Josh Vandiver Ball State University Various source media, Political Extremism and Radicalism in the Twentieth Century EMPOWER™ RESEARCH The radical political movement known as the Alt-Right Revolution, and Evolian Traditionalism – for an is, without question, a twenty-first century American audience. phenomenon.1 As the hipster-esque ‘alt’ prefix 3. A refined and intensified gender politics, a suggests, the movement aspires to offer a youthful form of ‘ultra-masculinism.’ alternative to conservatism or the Establishment Right, a clean break and a fresh start for the new century and .2 the Millennial and ‘Z’ generations While the first has long been a feature of American political life (albeit a highly marginal one), and the second has been paralleled elsewhere on the Unlike earlier radical right movements, the Alt-Right transnational right, together the three make for an operates natively within the political medium of late unusual fusion. modernity – cyberspace – because it emerged within that medium and has been continuously shaped by its ongoing development. This operational innovation will Seminal Alt-Right figures, such as Andrew Anglin,4 continue to have far-reaching and unpredictable Richard Spencer,5 and Greg Johnson,6 have been active effects, but researchers should take care to precisely for less than a decade. While none has continuously delineate the Alt-Right’s broader uniqueness. designated the movement as ‘Alt-Right’ (including Investigating the Alt-Right’s incipient ideology – the Spencer, who coined the term), each has consistently ferment of political discourses, images, and ideas with returned to it as demarcating the ideological territory which it seeks to define itself – one finds numerous they share. -

The Alt-Right on Campus: What Students Need to Know

THE ALT-RIGHT ON CAMPUS: WHAT STUDENTS NEED TO KNOW About the Southern Poverty Law Center The Southern Poverty Law Center is dedicated to fighting hate and bigotry and to seeking justice for the most vulnerable members of our society. Using litigation, education, and other forms of advocacy, the SPLC works toward the day when the ideals of equal justice and equal oportunity will become a reality. • • • For more information about the southern poverty law center or to obtain additional copies of this guidebook, contact [email protected] or visit www.splconcampus.org @splcenter facebook/SPLCenter facebook/SPLConcampus © 2017 Southern Poverty Law Center THE ALT-RIGHT ON CAMPUS: WHAT STUDENTS NEED TO KNOW RICHARD SPENCER IS A LEADING ALT-RIGHT SPEAKER. The Alt-Right and Extremism on Campus ocratic ideals. They claim that “white identity” is under attack by multicultural forces using “politi- An old and familiar poison is being spread on col- cal correctness” and “social justice” to undermine lege campuses these days: the idea that America white people and “their” civilization. Character- should be a country for white people. ized by heavy use of social media and memes, they Under the banner of the Alternative Right – or eschew establishment conservatism and promote “alt-right” – extremist speakers are touring colleges the goal of a white ethnostate, or homeland. and universities across the country to recruit stu- As student activists, you can counter this movement. dents to their brand of bigotry, often igniting pro- In this brochure, the Southern Poverty Law Cen- tests and making national headlines. Their appear- ances have inspired a fierce debate over free speech ter examines the alt-right, profiles its key figures and the direction of the country. -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Thevanderbilt Political Review

TheVanderbilt Political Review F I I N HE I E E S I L L NG T P C Spring 2011 TheVanderbilt VPR | Spring 2011 Political Review Table of Contents Spring 2011 • Volume 4 • Issue 2 President Matthew David Taylor 3 Interview with Dr. William Turner Vice Presidents Allegra Noonan Interview conducted by Britt Johnson Nathan Rothschild and Sid Sapru Editor-in-Chief Libby Marden 4 Alumni Perspective: Assistant Editor-in-Chief Sid Sapru A Conversation with President George W. Bush Online Director Noah Fram Wyatt Smith Events Director Leia Andrew Zaid Choudhry College of Arts & Science and Secretary Hannah Jarmolowski Peabody College Treasurer Ryan Higgins Class of 2010 Public Relations Melissa O’Neill 6 The Red Sea Art Director Eric Lyons Nick Vance Director of Layout Melissa McKittrick College of Arts & Science Community Outreach Nick Vance Class of 2014 Print Editors Eliza Horn 7 The Unfinished Revolution: Egypt’s Transition to Vann Bentley Civilian Rule Nathan Rothschild Sloane Speakman Christina Rogers College of Arts & Science Hannah Rogers Class of 2012 Andrea Clabough Emily Morgenstern 9 A Hopeful Pakistan, A Hopeful America Nicholas Vance Sanah Ladhani College of Arts & Science Online Writers Megan Covington Class of 2012 Mark Cherry 10 Wrapped in the Flag and Carrying a Cross Adam Osiason Eric Lyons John Foshee Jillian Hughes College of Arts & Science Jeff Jay Class of 2014 12 The Libyan No Fly-Zone: A New Paradigm for Events Staff Michal Durkiewicz Humanitarian Intervention and Reinforcing Democracy Jennifer Miao Atif Choudhury Caitlin Rooney College of Arts & Science Kenneth Colonel Alex Smalanskas-Torres Class of 2011 13 Who Failed Our Country’s Children? Faculty Adviser Mark Dalhouse Zach Blume College of Arts & Science Class of 2014 Vanderbilt‘s first and only multi-partisan academic journal 14 Exorcising the Boogeyman featuring essays pertaining to political, social, and economic events that are taking place in our world as we speak.