And the Aesthetics of Doom, 2001 Page 1/22

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CLAES OLDENBURG by Barbara Rose, the First Comprehensive Treatment of Oldenburg's

No. 56 V»< May 31, 1970 he Museum of Modern Art FOR IMT4EDIATE RELEASE jVest 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 956-6100 Cable: Modernart (N.B. Publication date of book: September 8) CLAES OLDENBURG by Barbara Rose, the first comprehensive treatment of Oldenburg's life and art, will be published by The Museum of Modern Art on September 8, 1970. Richly illustrated with 224 illustrations in black-and-white and 52 in color, this monograph, which will retail at $25, has a highly tactile., flexible binding of vinyl over foam-rubber padding, making it a "soft" book suggestive of the artist's well- known "soft" sculptures. Oldenburg came to New York from Chicago in 1956 and settled on the Lower East Side, at that time a center for young artists whose rebellion against the dominance of Abstract Expressionism and search for an art more directly related to their urban environment led to Pop Art. Oldenburg himself has been regarded as perhaps the most interesting artist to emerge from that movement — "interesting because he transcends it," in the words of Hilton Kramer, art critic of the New York Times. As Miss Rose points out, however, Oldenburg's art cannot be defined by the label of any one movement. His imagination links him with the Surrealists, his pragmatic thought with such American philosophers as Henry James and John Dewey, his handling of paint in his early Store reliefs with the Abstract Expressionists, his subject matter with Pop Art, and some of his severely geometric, serial forms with the Mini malists. -

Introduction and Will Be Subject to Additions and Corrections the Early History of El Museo Del Barrio Is Complex

This timeline and exhibition chronology is in process INTRODUCTION and will be subject to additions and corrections The early history of El Museo del Barrio is complex. as more information comes to light. All artists’ It is intertwined with popular struggles in New York names have been input directly from brochures, City over access to, and control of, educational and catalogues, or other existing archival documentation. cultural resources. Part and parcel of the national We apologize for any oversights, misspellings, or Civil Rights movement, public demonstrations, inconsistencies. A careful reader will note names strikes, boycotts, and sit-ins were held in New York that shift between the Spanish and the Anglicized City between 1966 and 1969. African American and versions. Names have been kept, for the most part, Puerto Rican parents, teachers and community as they are in the original documents. However, these activists in Central and East Harlem demanded variations, in themselves, reveal much about identity that their children— who, by 1967, composed the and cultural awareness during these decades. majority of the public school population—receive an education that acknowledged and addressed their We are grateful for any documentation that can diverse cultural heritages. In 1969, these community- be brought to our attention by the public at large. based groups attained their goal of decentralizing This timeline focuses on the defining institutional the Board of Education. They began to participate landmarks, as well as the major visual arts in structuring school curricula, and directed financial exhibitions. There are numerous events that still resources towards ethnic-specific didactic programs need to be documented and included, such as public that enriched their children’s education. -

The Effect of War on Art: the Work of Mark Rothko Elizabeth Leigh Doland Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2010 The effect of war on art: the work of Mark Rothko Elizabeth Leigh Doland Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Doland, Elizabeth Leigh, "The effect of war on art: the work of Mark Rothko" (2010). LSU Master's Theses. 2986. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2986 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EFFECT OF WAR ON ART: THE WORK OF MARK ROTHKO A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Arts in The Interdepartmental Program in Liberal Arts by Elizabeth Doland B.A., Louisiana State University, 2007 May 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT…………………………………………………………………iii CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION……………………………………………........1 2 EARLY LIFE……………………………………………………....3 Yale Years……………………………………………………6 Beginning Life as Artist……………………………………...7 Milton Avery…………………………………………………9 3 GREAT DEPRESSION EFFECTS………………………………...13 Artists’ Union………………………………………………...15 The Ten……………………………………………………….17 WPA………………………………………………………….19 -

18 Works from the Bachman Collection (1606) Lot 2

18 Works from the Bachman Collection (1606) June 4, 2018 EDT Lot 2 Estimate: $150000 - $250000 (plus Buyer's Premium) Hans Hofmann (American/German, 1880-1966) Cataclysm (Homage to Howard Putzel) Signed, dated 'August 11 - 1945' and inscribed 'hommage to howard putzel,' bottom right, oil and casein on board. [HH no. 562-1945; Estate no. M-0264] 51 3/4 x 48 in. (131.4 x 121.9cm) Provenance: The Estate of the Artist. André Emmerich Gallery, New York, New York (acquired directly from the above in 1986). The Estate of Lee & Gilbert Bachman, Atlanta, Georgia & Boca Raton, Florida (acquired directly from the above in 1986). EXHIBITED: "Hans Hofmann: Recent Paintings," Mortimer Brandt Gallery, New York, March 18 - 30, 1946. "Seeing the Unseeable," Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, Andover, Massachusetts, January 3 - March 3, 1947. "Hans Hofmann: Early Paintings," Kootz Gallery, New York, January 20 - 31, 1959. "Hans Hofmann: A Retrospective Exhibition," a traveling exhibition: Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C., October 14, 1976 - January 2, 1977; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas, February 4 - April 3, 1977, p. 51 (illustrated in the exhibition catalogue). "Abstract Expressionism: The Formative Years," a traveling exhibition: Howard F. Johnson Museum of Art, March 1 - June 1, 1978; Seibu Museum, Karuizawa, Japan, June - July, 1978; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, September 1 - December 1, 1978, p. 80 (illustrated in the exhibition catalogue). "Flying Tigers: Painting and Sculpture in New York, 1939 - 1946," a traveling exhibition: Bell Gallery, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, April 26 - May 27, 1985; Parrish Art Museum, Southampton, Long Island, New York, June 9 - July 28, 1985. -

Hedda Sterne and Abstract Expressionism

1 Menacing Machines and Sublime Cities: Hedda Sterne and Abstract Expressionism Tasia Kastanek Art History Honors Thesis April 12, 2011 Primary Advisor: Kira van Lil – Art History Committee Members: Robert Nauman – Art History Nancy Hightower – Writing and Rhetoric 2 Abstract: The canon of Abstract Expressionism ignores the achievements of female painters. This study examines one of the neglected artists involved in the movement, Hedda Sterne. Through in-depth analysis of her Machine series and New York, New York series, this study illuminates the differences and similarities of Sterne‟s paintings to the early stages of Abstract Expressionism. Sterne‟s work both engages with and expands the discussions of “primitive” signs, the sublime and urban abstraction. Her early training in Romania and experience of WWII as well as her use of mechanical symbols and spray paint contribute to a similar yet unique voice in Abstract Expressionism. Table of Contents Introduction: An Inner Necessity and Flight from Romania…….…………..……………….3 Machines: Mechanolatry, War Symbolism and an Ode to Tractors……………………......13 New York, New York: Masculine Subjectivity, Urban Abstraction and the Sublime...…...26 Instrument vs. Actor: Sterne’s Artistic Roles………………..………………………….……44 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………………49 Images…………………………………………………………………………………………...52 Works Cited……………………………………………………………………………………..67 3 “Just as each spoken word rouses an internal vibration, so does every object represented. To deprive oneself of this possibility of causing a vibration -

Draft July 6, 2011

Reinhardt, Martin, Richter: Colour in the Grid of Contemporary Painting by Milly Mildred Thelma Ristvedt A thesis submitted to the Graduate Program in Art History, Department of Art in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Queen‘s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada Final submission, September, 2011 Copyright ©Milly Mildred Thelma Ristvedt, 2011 Abstract The objective of my thesis is to extend the scholarship on colour in painting by focusing on how it is employed within the structuring framework of the orthogonal grid in the paintings of three contemporary artists, Ad Reinhardt, Agnes Martin and Gerhard Richter. Form and colour are essential elements in painting, and within the ―essentialist‖ grid painting, the presence and function of colour have not received the full discussion they deserve. Structuralist, post-structuralist and anthropological modes of critical analysis in the latter part of the twentieth century, framed by postwar disillusionment and skepticism, have contributed to the effective foreclosure of examination of metaphysical, spiritual and utopian dimensions promised by the grid and its colour earlier in the century. Artists working with the grid have explored, and continue to explore the same eternally vexing problems and mysteries of our existence, but analyses of their art are cloaked in an atmosphere and language of rationalism. Critics and scholars have devoted their attention to discussing the properties of form, giving the behavior and status of colour, as a property affecting mind and body, little mention. The position of colour deserves to be re-dressed, so that we may have a more complete understanding of grid painting as a discrete kind of abstract painting. -

PAVIA, PHILIP, 1915-2005. Philip Pavia and Natalie Edgar Archive of Abstract Expressionist Art, 1913-2005

PAVIA, PHILIP, 1915-2005. Philip Pavia and Natalie Edgar archive of abstract expressionist art, 1913-2005 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Descriptive Summary Creator: Pavia, Philip, 1915-2005. Title: Philip Pavia and Natalie Edgar archive of abstract expressionist art, 1913-2005 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 981 Extent: 38 linear feet (68 boxes), 5 oversized papers boxes and 5 oversized papers folders (OP), 1 extra oversized papers folder (XOP) and AV Masters: 1 linear foot (1 box) Abstract: Philip Pavia and Natalie Edgar archive of abstract expressionist art including writings, photographs, legal records, correspondence, and records of It Is, the 8th Street Club, and the 23rd Street Workshop Club. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Unrestricted access. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction All requests subject to limitations noted in departmental policies on reproduction. Source Purchase, 2004. Additions purchased from Natalie Edgar, 2018. Citation [after identification of item(s)], Philip Pavia and Natalie Edgar archive of abstract expressionist art, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University. Processing Processed by Elizabeth Russey and Elizabeth Stice, October 2009. Additions added to the collection in 2018 retain the original order in which they were received. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. Philip Pavia and Natalie Edgar archive of abstract expressionist art, Manuscript Collection No. -

University Microfilms International 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 USA St

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find e good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

BARBARA ROSE P.,

The Museum of Modern Art No. 78 BARBARA ROSE p., .. „ Public information Barbara Rose organized LEE KRASNER: A RETROSPECTIVE for the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, where she is Consulting Curator, and collaborated in its installation at The Museum of Modern Art. She received a B.A. from Barnard College and a Ph.D. in the History of Art from Columbia University. In 1961- 62, she was a Fulbright Fellow to Spain. She has taught at Yale University; Sarah Lawrence and Hunter Colleges; the University of California, Irvine; and was Regent's Professor at the University of California, San Diego. A prominent critic of contemporary art, Miss Rose is currently an associate editor of Arts Magazine and Partisan Review. She was formerly New York correspondent for Art International and a contributing editor to Artforum and Art in America. Her writings have twice received the College Art Associa tion Frank Jewett Mather Award for Distinguished Art Criticism. Miss Rose has curated and co-curated many exhibitions, including Claes Oldenburg (1969); Patrick Henry Bruce - An American Modernist (1980); Lee Krasner - Jackson Pollock: A Working Relationship (1980); and Miro in America (1982). She has recently co-authored the exhibition catalogues Leger and the Modern Spirit (1982) and Goya: The "Disasters of War" and Selected Prints from the Collection of the Arthur Roth Foundation (1984). In addition to the catalogue accompanying LEE KRASNER: A RETROSPECTIVE, Miss Rose is the author and editor of American Painting, American Art Since 1900, Readings in American Art, and several monographs. She has also made films on American artists, among them North Star: Mark di Suvero, Sculptor, and Lee Krasner: The Long View, a Cine Film Festival Gold Eagle Recipient in 1980. -

BOOKS ABOUT ARTISTS Catalogue 72 – January 2013

BOOKS ABOUT ARTISTS Catalogue 72 – January 2013 1. (Aaltonen, Waino). WAINO AALTONEN by Onni Okkonen. Finland, 1945. 4to., boards, DJ, 31pp. text, 96 illustrations of sculpture in photogravure. Text in Swedish and Finnish. VG/VG $12.50 2. (Adam, Robert). ROBERT ADAM & HIS BROTHERS - Their Lives, Work & Influence by John Swarbrick. Scribners, NY, 1915. 4to., 316pp., t.e.g., illustrated. An important reference on one the leading British architect/designers of the 18th Century. A near fine copy. $125.00 3. (Albers, Josef). THE PRINTS OF JOSEF ALBERS - A CATALOGUE RAISONNE1915-1976 by Brenda Danilowitz. Hudson Hills Press, NY, 2001. 4to., cloth, DJ, 215pp. illustrated. Fine in Fine DJ. $75.00 4. (Albright, Ivan). IVAN ALBRIGHT by Michael Croydon. Abbeville, NY, 1978. Folio, cloth, DJ, 308pp., 170 illustrations, 83 in color. F/F $100.00 5. Ali. BEYOND THE BIG TOP. Godine/Pucker Safrai, Boston, 1988. Obl. 4to., cloth, DJ, text and 97 works illustrated, mostly in color. Fine/Fine. $10.00 6. (Allemand, Louis-Hector). LOUIS-HECTOR ALLEMAND - PEINTRE GRAVEUR LYONNAIS 1809-1886 by Paul Proute et al. Paris, 1977. 4to., wraps, 82 prints pictured and described. Fine. $25.00 7. (Allori et al, Allessandro). FROM STUDIO TO STUDIOLO - FLORENTINE DRAFTSMANSHIP UNDER THE FIRST MEDICI GRAND DUKES by Larry J. Feinberg. Oberlin, 1991. 4to., wraps, 211pp, 60 items catalogued and illustrated. Fine. $17.50 8. (Allston, Washington). "A MAN OF GENIUS" - THE ART OF WASHINGTON ALLSTON by Gerdts and Stebbins. MFA< boston, 1979. 4to., cloth, DJ, 256pp., 24 color plates, 162 b/w illustrations. Fine, DJ has white spots on back panel. -

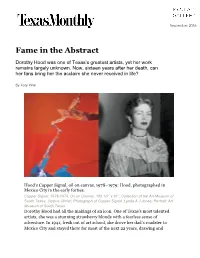

Fame in the Abstract

September 2016 Fame in the Abstract Dorothy Hood was one of Texas’s greatest artists, yet her work remains largely unknown. Now, sixteen years after her death, can her fans bring her the acclaim she never received in life? By Katy Vine Hood’s Copper Signal, oil on canvas, 1978–1979; Hood, photographed in Mexico City in the early forties. Copper Signal, 1978-1979, Oil on Canvas, 109 1/2” x 81”; Collection of the Art Museum of South Texas, Corpus Christi; Photograph of Copper Signal: Lynda A J Jones; Portrait: Art Museum of South Texas Dorothy Hood had all the makings of an icon. One of Texas’s most talented artists, she was a stunning strawberry blonde with a fearless sense of adventure. In 1941, fresh out of art school, she drove her dad’s roadster to Mexico City and stayed there for most of the next 22 years, drawing and painting alongside Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, Roberto Montenegro, and Miguel Covarrubias. Pablo Neruda wrote a poem about her paintings. José Clemente Orozco befriended and encouraged her. The Bolivian director and composer José María Velasco Maidana fell hard for her and later married her. And after a brief stretch in New York City, she and Maidana moved to her native Houston, where she produced massive paintings of sweeping color that combined elements of Mexican surrealism and New York abstraction in a way that no one had seen before, winning her acclaim and promises from museums of major exhibits. She seemed on the verge of fame. “She certainly is one of the most important artists from that generation,” said art historian Robert Hobbs. -

Minimalism and Postminimalism

M i n i m a l i s m a n d P o s t m i n i m a l i s m : t h e o r i e s a n d r e p e r c u s s i o n s Department of Art History, Theory, and Criticism 4372 The School of the Art Institute of Chicago David Getsy, Instructor [[email protected]] Spring 2000 / Tuesdays 9 am - 12 pm / Champlain 319 c o u r s e de s c r i pt i o n Providing an in-depth investigation into the innovations in art theory and practice commonly known as “Minimalism” and “Postminimalism,” the course follows the development of Minimal stylehood and tracks its far-reaching implications. Throughout, the greater emphasis on the viewer’s contribution to the aesthetic encounter, the transformation of the role of the artist, and the expanded definition of art will be examined. Close evaluations of primary texts and art objects will form the basis for a discussion. • • • m e t h o d o f e va l u a t i o n Students will be evaluated primarily on attendance, preparation, and class discussion. All students are expected to attend class meetings with the required readings completed. There will be two writing assignments: (1) a short paper on a relevant artwork in a Chicago collection or public space due on 28 March 2000 and (2) an in- class final examination to be held on 9 May 2000. The examination will be based primarily on the readings and class discussions.