Framing Cultural Ecosystem Services in the Andes: Utawallu As Sentinels of Values for Biocultural Heritage Conservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Otavaleños and Cotacacheños: Local Perceptions of Sacred Sites for Farmscape Conservation in Highland Ecuador

© Kamla-Raj 2011 J Hum Ecol, 35(1): 61-70 (2011) Otavaleños and Cotacacheños: Local Perceptions of Sacred Sites for Farmscape Conservation in Highland Ecuador Lee Ellen Carter and Fausto O. Sarmiento* Honors Program and Department of Geography, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, 30602, USA E-mail: <[email protected] >, *< [email protected]> KEYWORDS Sacred Sites. Indigenous Conservation. Intangibles. Otavalo. Ecuador. Andes ABSTRACT Indigenous communities around the world face pressures from ecotourism practices and conservation. Otavalo, Ecuador, is an example of how local spiritual values can add to the conservation efforts of ecotourism. The Imbakucha watershed includes mountain landscapes with natural and cultural values of numerous indigenous communities where most residents associate their livelihood with iconic, sacred, natural features. Because this region has been conserved with a vibrant artisan economy, it is a well-known cultural landscape in Latin America, and therefore, the increased pressure of globalization affects its preservation as it undergoes a shift from traditional towards contemporary ecotourism practices. We investigate the relationship between the indigenous people and their intangible spiritual environment by local understanding of identity and cultural values, using ethnographic and qualitative research to analyze the influence of spirituality on environmental actions and intersections that reify the native sacred translated into Christianity, to define synchronisms of modernity and the ancestral influence on the Andean culture in the Kichwa Otavalo living in the valley. This study concludes that there is an outlook among indigenous leaders, politicians, researchers, and scholars that a stronger influence of environmental ideals and ecofriendly lifestyles should and can be instilled into the livelihood that exists in indigenous communities to favor sacred sites conservation with development. -

The Position of Indigenous Peoples in the Management of Tropical Forests

THE POSITION OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES IN THE MANAGEMENT OF TROPICAL FORESTS Gerard A. Persoon Tessa Minter Barbara Slee Clara van der Hammen Tropenbos International Wageningen, the Netherlands 2004 Gerard A. Persoon, Tessa Minter, Barbara Slee and Clara van der Hammen The Position of Indigenous Peoples in the Management of Tropical Forests (Tropenbos Series 23) Cover: Baduy (West-Java) planting rice ISBN 90-5113-073-2 ISSN 1383-6811 © 2004 Tropenbos International The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Tropenbos International. No part of this publication, apart from bibliographic data and brief quotations in critical reviews, may be reproduced, re-recorded or published in any form including print photocopy, microfilm, and electromagnetic record without prior written permission. Photos: Gerard A. Persoon (cover and Chapters 1, 2, 3, 4 and 7), Carlos Rodríguez and Clara van der Hammen (Chapter 5) and Barbara Slee (Chapter 6) Layout: Blanca Méndez CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 1. INDIGENOUS PEOPLES AND NATURAL RESOURCE 3 MANAGEMENT IN INTERNATIONAL POLICY GUIDELINES 1.1 The International Labour Organization 3 1.1.1 Definitions 4 1.1.2 Indigenous peoples’ position in relation to natural resource 5 management 1.1.3 Resettlement 5 1.1.4 Free and prior informed consent 5 1.2 World Bank 6 1.2.1 Definitions 7 1.2.2 Indigenous Peoples’ position in relation to natural resource 7 management 1.2.3 Indigenous Peoples’ Development Plan and resettlement 8 1.3 UN Draft Declaration on the -

Ecuador and the Galapagos Islands

GEODYSSEY ECUADOR AND THE GALAPAGOS ISLANDS Travel guides to Ecuador and the Galapagos Islands Planning your trip Where to stay Private guided touring holidays Small group holidays Galapagos cruises Walking holidays Specialist birdwatching ECUADOR 05 Ecuador Guide 22 Private guided touring 28 Small group holidays Ecuador has more variety packed into a Travel with a guide for the best of Ecuador Join a convivial small group holiday smaller space than anywhere else in South 22 Andes, Amazon and Galapagos 28 Ecuador Odyssey America The classic combination Ecuador's classic highlights in a 2 week 05 Quito fully escorted small group holiday 22 A Taste of Ecuador Our guide to one of Latin America's most A few days on the mainland before a remarkable cities 30 Active Ecuador Galapagos cruise 30 07 Where to stay in Quito Ecuador Adventures ð 23 Haciendas of Distinction Plenty of action for lively couples, friends Suggestions from amongst our favourites Discover the very best and active families 09 Andes 23 Quito City Break 31 Trek to Quilotoa Snow-capped volcanoes, fabulous scenery, Get to know Quito like a native Great walking staying at rural guesthouses llamas and highland communities 24 Nature lodges 32 Day Walks in the Andes 13 Haciendas and hotels for touring ð ð Lodges for the best nature experiences Explore and get fit on leg-stretching day Country haciendas and fine city hotels walks staying in comfortable hotels 25 15 Amazon Creature Comforts Wonderful nature experiences in 33 Cotopaxi Ascent The lushest and most interesting part of -

Committee on Development and Intellectual Property (CDIP)

E CDIP/21/INF/5 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH DATE: APRIL 11, 2018 Committee on Development and Intellectual Property (CDIP) Twenty-First Session Geneva, May 14 to 18, 2018 SUMMARY OF THE STUDY ON “INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY: A MECHANISM FOR STRENGTHENING PROVINCIAL IDENTITY WITHIN THE FRAMEWORK OF THE IMBABURA GEOPARK PROJECT” prepared by Mr. Sebastián Barrera, Founder, Creative Director, Kompany Latam, Quito 1. The Annex to this document contains a summary of the study on “Intellectual Property: A Mechanism for Strengthening Provincial Identity within the Framework of the Imbabura Geopark Project” undertaken in the context of the Project on Intellectual Property, Tourism and Culture: Supporting Development Objectives and Promoting Cultural Heritage in Egypt and Other Developing Countries (document CDIP/15/7 Rev.). 2. The study has been prepared by Mr. Sebastián Barrera, Founder, Creative Director, Kompany Latam, Quito. 3. The CDIP is invited to take note of the information contained in the Annex to the present document. [Annex follows] CDIP/21/INF/5 ANNEX Intellectual Property: A Mechanism for Strengthening Provincial Identity within the Framework of the Imbabura Geopark Project SUMMARY The study conducted within the framework of the Intellectual Property, Tourism and Culture project in connection with the Imbabura Geopark Project seeks to serve as a support tool for identifying the existing tourist offer in the province of Imbabura, in order to associate it with intellectual property. A summary is provided below. The study starts with an overview of the environment and the tourist offer, presenting indices of the tourist sector, such as the type of foreign visitors to Ecuador. There is also an overview of the management of local tourism in the province of Imbabura. -

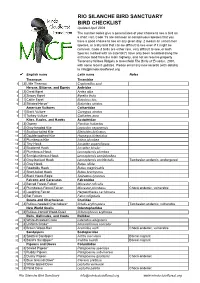

RIO SILANCHE BIRD SANCTUARY BIRD CHECKLIST Updated April 2008 the Number Codes Give a General Idea of Your Chance to See a Bird on a Short Visit

RIO SILANCHE BIRD SANCTUARY BIRD CHECKLIST Updated April 2008 The number codes give a general idea of your chance to see a bird on a short visit. Code 1's are common or conspicuous species that you have a good chance to see on any given day. 2 means an uncommon species, or a shy bird that can be difficult to see even if it might be common. Code 3 birds are either rare, very difficult to see, or both. Species marked with an asterisk(*) have only been recorded along the entrance road from the main highway, and not on reserve property. Taxonomy follows Ridgely & Greenfield The Birds of Ecuador , 2001, with some recent updates. Please email any new records (with details) to [email protected]. English name Latin name Notes Tinamous Tinamidae 1 3 Little Tinamou Crypturellus soui Herons, Bitterns, and Egrets Ardeidae 2 2 Great Egret Ardea alba 3 2 Snowy Egret Egretta thula 4 1 Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis 5 3 Striated Heron* Butorides striatus American Vultures Cathartidae 6 1 Black Vulture Coragyps atratus 7 1 Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura Kites, Eagles, and Hawks Accipitridae 8 3 Osprey Pandion haliaetus 9 2 Gray-headed Kite Leptodon cayanensis 10 1 Swallow-tailed Kite Elanoides forficatus 11 2 Double-toothed Kite Harpagus bidentatus 12 2 Plumbeous Kite Ictinia plumbea 13 3 Tiny Hawk Accipiter superciliosus 14 3 Bicolored Hawk Accipiter bicolor 15 2 Plumbeous Hawk Leucopternis plumbea 16 3 Semiplumbeous Hawk Leucopternis semiplumbea 17 3 Gray-backed Hawk Leucopternis occidentalis Tumbesian endemic, endangered 18 2 Gray Hawk Buteo nitida -

COLOMBIA 2019 Ned Brinkley Departments of Vaupés, Chocó, Risaralda, Santander, Antioquia, Magdalena, Tolima, Atlántico, La Gu

COLOMBIA 2019 Ned Brinkley Departments of Vaupés, Chocó, Risaralda, Santander, Antioquia, Magdalena, Tolima, Atlántico, La Guajira, Boyacá, Distrito Capital de Bogotá, Caldas These comments are provided to help independent birders traveling in Colombia, particularly people who want to drive themselves to birding sites rather than taking public transportation and also want to book reservations directly with lodgings and reserves rather than using a ground agent or tour company. Many trip reports provide GPS waypoints for navigation. I used GoogleEarth/ Maps, which worked fine for most locations (not for El Paujil reserve). I paid $10/day for AT&T to hook me up to Claro, Movistar, or Tigo through their Passport program. Others get a local SIM card so that they have a Colombian number (cheaper, for sure); still others use GooglePhones, which provide connection through other providers with better or worse success, depending on the location in Colombia. For transportation, I used a rental 4x4 SUV to reach places with bad roads but also, in northern Colombia, a subcompact rental car as far as Minca (hiked in higher elevations, with one moto-taxi to reach El Dorado lodge) and for La Guajira. I used regular taxis on few occasions. The only roads to sites for Fuertes’s Parrot and Yellow-eared Parrot could not have been traversed without four-wheel drive and high clearance, and this is important to emphasize: vehicles without these attributes would have been useless, or become damaged or stranded. Note that large cities in Colombia (at least Medellín, Santa Marta, and Cartagena) have restrictions on driving during rush hours with certain license plate numbers (they base restrictions on the plate’s final numeral). -

272020Including0the0excluded0

The World Bank, 1996 Public Disclosure Authorized INCLUDING THE EXCLUDED: ETHNODEVELOPMENT IN LATIN AMERICA William L. Partridge and Jorge E. Uquillas with Kathryn Johns Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized The World Bank Latin America and the Caribbean Technical Department Environment Unit Public Disclosure Authorized Presented at the Annual World Bank Conference on Development in Latin America and the Caribbean, Bogotá, Colombia, June 30 - July 2, 1996. This paper has benefited from comments by Salomon Nahmad, Billie DeWalt, Shelton Davis, Jackson Roper and Arturo Argueta, to whom the authors are very grateful. The World Bank, 1996 Including the Excluded: Ethnodevelopment in Latin America William L. Partridge and Jorge E. Uquillas with Kathryn Johns Lift up your faces, you have a piercing need For this bright morning dawning for you. History, despite its wrenching pain, Cannot be unlived, but if faced With courage, need not be lived again. Maya Angelou 2 The World Bank, 1996 INTRODUCTION 1. At the start of the U.N. International Decade for Indigenous Peoples (1995-2004), indigenous peoples in Latin America, the original inhabitants, live in some of the poorest and most marginal conditions. After enduring centuries of domination, forced assimilation and most recently the devastating effects of disease, conflict and poverty, indigenous peoples in Latin America have survived and become engaged in fierce struggles for rights to their land and resources and their freedom of cultural expression. This paper explores the conditions which have enabled indigenous peoples to respond to changing circumstances in their communities, the development strategies that are emerging at the grassroots level, and some of the lessons and opportunities that should be taken by the Bank to assist indigenous peoples to improve their lives while maintaining and strengthening their cultures. -

Caracterización De Depósitos De Corriente De Densidad Piroclástica Asociados a La Caldera De Cuicocha, Norte De Los Andes Ecuatorianos

UNIVERSIDAD DE INVESTIGACIÓN DE TECNOLOGÍA EXPERIMENTAL YACHAY Escuela de Ciencias de la Tierra, Energía y Ambiente TÍTULO: CARACTERIZACIÓN DE DEPÓSITOS DE CORRIENTE DE DENSIDAD PIROCLÁSTICA ASOCIADOS A LA CALDERA DE CUICOCHA, NORTE DE LOS ANDES ECUATORIANOS. Trabajo de integración curricular presentado como requisito para la obtención del título de Geóloga Autor: Patricia Janeth Rengel Calvopiña Tutor: Ph. D. Almeida Gonzalez Rafael Urcuquí, Julio 2020 AUTORÍA Yo, Patricia Janeth Rengel Calvopiña, con cédula de identidad 1725202830, declaro que las ideas, juicios, valoraciones, interpretaciones, consultas bibliográficas, definiciones y conceptualizaciones expuestas en el presente trabajo; así cómo, los procedimientos y herramientas utilizadas en la investigación, son de absoluta responsabilidad de el/la autora (a) del trabajo de integración curricular. Así mismo, me acojo a los reglamentos internos de la Universidad de Investigación de Tecnología Experimental Yachay. Urcuquí, Julio 2020. ___________________________ Patricia Janeth Rengel Calvopiña CI: 1725202830 AUTORIZACIÓN DE PUBLICACIÓN Yo, Patricia Janeth Rengel Calvopiña, con cédula de identidad 1725202830, cedo a la Universidad de Tecnología Experimental Yachay, los derechos de publicación de la presente obra, sin que deba haber un reconocimiento económico por este concepto. Declaro además que el texto del presente trabajo de titulación no podrá ser cedido a ninguna empresa editorial para su publicación u otros fines, sin contar previamente con la autorización escrita de la Universidad. Asimismo, autorizo a la Universidad que realice la digitalización y publicación de este trabajo de integración curricular en el repositorio virtual, de conformidad a lo dispuesto en el Art. 144 de la Ley Orgánica de Educación Superior Urcuquí, Julio 2020. ___________________________ Patricia Janeth Rengel Calvopiña CI: 1725202830 “El mayor desafío que enfrentan nuestros países de cara al futuro como naciones con doscientos años de independencia es la educación. -

The First Geopark in Ecuador: Imbabura

EDITORIAL - The First Geopark in Ecuador: Imbabura. EDITORIAL The First Geopark in Ecuador: Imbabura. Yaniel Misael Vázquez Taset and Andrea Belén Tonato Ñacato DOI. 10.21931/RB/2019.04.01.1 The UNESCO Global Geoparks are created in the nineties as Geoparks composed specific geographic areas that show particular a European regional initiative to respond the increasing need for and relevant geological features of our planet’s history (UNESCO enhancing and preserving the geological heritage of our planet 1, 4). In South America, and principally in the Andean zone, the evi- based on the geological record of determined areas. These geo- dence associated to the convergence and subduction of the Nazca 830 graphic sites are part of the evidence of the 4600 Ma of Earth’s Plate and South American Plate is well preserved. For this reason, evolution. This initiative is based on three essential pillars 2: pres- there is a wide variety of natural and geological attractions (rang- ervation, education and geo – tourism designed to reach the sus- es of different ages, valleys, volcanoes, geothermal systems, sed- tainable economic development based on the harnessing of the imentary basins, faults, rocks, minerals, fossils, etc.). The beauty geological heritage. These main thrusts are the guidelines to man- and the showiness of the region have motivated the launching of age Geoparks, and give the possibility to develop economic and various Geopark proposals, for example: Napo – Sumaco in the touristic activities which increase the economic income in com- Amazon Region, Península Santa Elena and Jama – Pedernales in munities. As a consequence, the settler’s life’s quality is positively the Coast, Galápagos in the Insular Region, and Volcán Tungura- affected. -

In Ecuador, Will Mining Firms Win in Long Run? Luis ÃNgel Saavedra

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository NotiSur Latin America Digital Beat (LADB) 12-5-2014 In Ecuador, Will Mining Firms Win in Long Run? Luis Ãngel Saavedra Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/notisur Recommended Citation Ãngel Saavedra, Luis. "In Ecuador, Will Mining Firms Win in Long Run?." (2014). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/notisur/ 14293 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Latin America Digital Beat (LADB) at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in NotiSur by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LADB Article Id: 79495 ISSN: 1060-4189 In Ecuador, Will Mining Firms Win in Long Run? by Luis Ángel Saavedra Category/Department: Ecuador Published: 2014-12-05 Intag, a group of several communities in Ecuador’s Imbabura province, had been seen as an enduring example of resistance to the mining industry. But its history could end up being repeated in other communities where mineral companies are granted concessions and then harassment, lawsuits against leaders, forced land sales, displacement, and other actions by government and corporations discourage the local population, weakening how people organize and struggle. Today, after 20 years of struggle, Intag is fragmented and unable to sustain its long-standing determination to defend its territories (NotiSur, March 14, 2014). History of resistance Approximately 17,000 people live in the Intag communities in the southwestern part of Cotacachi canton in Imbabura province, an area of cloud-covered forests and farms in the Andean highlands of northwestern Ecuador. -

Neotropical News Neotropical News

COTINGA 1 Neotropical News Neotropical News Brazilian Merganser in Argentina: If the survey’s results reflect the true going, going … status of Mergus octosetaceus in Argentina then there is grave cause for concern — local An expedition (Pato Serrucho ’93) aimed extinction, as in neighbouring Paraguay, at discovering the current status of the seems inevitable. Brazilian Merganser Mergus octosetaceus in Misiones Province, northern Argentina, During the expedition a number of sub has just returned to the U.K. Mergus tropical forest sites were surveyed for birds octosetaceus is one of the world’s rarest — other threatened species recorded during species of wildfowl, with a population now this period included: Black-fronted Piping- estimated to be less than 250 individuals guan Pipile jacutinga, Vinaceous Amazon occurring in just three populations, one in Amazona vinacea, Helmeted Woodpecker northern Argentina, the other two in south- Dryocopus galeatus, White-bearded central Brazil. Antshrike Biata s nigropectus, and São Paulo Tyrannulet Phylloscartes paulistus. Three conservation biologists from the U.K. and three South American counter PHIL BENSTEAD parts surveyed c.450 km of white-water riv Beaver House, Norwich Road, Reepham, ers and streams using an inflatable boat. Norwich, NR10 4JN, U.K. Despite exhaustive searching only one bird was located in an area peripheral to the species’s historical stronghold. Former core Black-breasted Puffleg found: extant areas (and incidently those with the most but seriously threatened. protection) for this species appear to have been adversely affected by the the Urugua- The Black-breasted Puffleg Eriocnemis í dam, which in 1989 flooded c.80 km of the nigrivestis has been recorded from just two Río Urugua-í. -

PRATT-THESIS-2019.Pdf

THE UTILITARIAN AND RITUAL APPLICATIONS OF VOLCANIC ASH IN ANCIENT ECUADOR by William S. Pratt, B.S. A thesis submitted to the Graduate Council of Texas State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Master of Arts with a Major in Anthropology August 2019 Committee Members: Christina Conlee, Chair David O. Brown F. Kent Reilly III COPYRIGHT by William S. Pratt 2019 FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT Fair Use This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94-553, section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgement. Use of this material for financial gain without the author’s express written permission is not allowed. Duplication Permission As the copyright holder of this work I, William S. Pratt, authorize duplication of this work, in whole or in part, for educational or scholarly purposes only. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Numerous people have contributed over the years both directly and indirectly to the line of intrigue that led me to begin this work. I would like to extend thanks to all of the members of my thesis committee. To Christina Conlee for her patience, council, and encouragement as well as for allowing me the opportunity to vent when the pressures of graduate school weighed on me. To F. Kent Reilly for his years of support and for reorienting me when the innumerable distractions of the world would draw my eye from my studies. And I especially owe a great deal of thanks to David O.