Music Department Program Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introducing the Iwatch

May 2014 Jun June 2014 Welcome to Volume 5, Issue 6 of iDevices (iPhone, iPod & iPad) SIG Meetings Need Help? Go to the iDevice FORUM, click HERE To find Apps that are free for a short time, click these 2 icons: Introducing the iWatch Click to see the video New iPhone Lock screen bypass discovered Here's how to protect against it! By Rene Ritchie, Monday, Jun 9, 2014 16 A new iOS 7.1.1 iPhone Lock screen bypass has been discovered. Lock screen bypasses in and of themselves aren't new — trying to protect a phone while also allowing access to convenient features results is an incredible tension — but this one can provide access to an app, which makes it one of the most serious to date. It does require physical access to your iPhone, but if you do lose possession, here's how the bypass works and, more importantly, how you can protect yourself from it. Note: iMore tested the exploit and its scope before reporting on it. We were able to duplicate it but also get a sense of its ramifications and limitations. First, in order to get around the passcode lock, this bypass requires that the iPhone be placed into Airplane mode, and that a missed phone call notification be present. When those conditions are met, tapping or swiping the missed call notification will cause a Settings popup to appear on top of whatever app was last active (in the foreground) on the iPhone prior to it being locked. Dismiss the popup and you have access to the app. -

Ios App Reverse Engineering

snakeninny, hangcom Translated by Ziqi Wu, 0xBBC, tianqing and Fei Cheng iOS App Reverse Engineering Table of Contents Recommendation ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 Preface ....................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Foreword ................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Part 1 Concepts ....................................................................................................................................................... 12 Chapter 1 Introduction to iOS reverse engineering ............................................................................................. 13 1.1 Prerequisites of iOS reverse engineering .......................................................................................................... 13 1.2 What does iOS reverse engineering do ............................................................................................................ 13 1.2.1 Security related iOS reverse engineering ...................................................................................................... 16 1.2.2 Development related iOS reverse engineering ............................................................................................ -

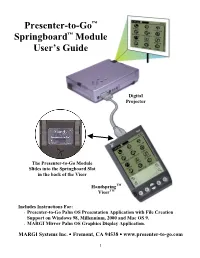

Presenter-To-Go™ Springboard™ Module User's Guide

Presenter-to-Go™ Springboard™ Module User’s Guide Digital Projector The Presenter-to-Go Module Slides into the Springboard Slot in the back of the Visor HandspringTM VisorTM Includes Instructions For: • Presenter-to-Go Palm OS Presentation Application with File Creation Support on Windows 98, Millennium, 2000 and Mac OS 9. • MARGI Mirror Palm OS Graphics Display Application. MARGI Systems Inc. • Fremont, CA 94538 • www.presenter-to-go.com 1 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ...............................................................................4 Your Product Packaging Contains:.......................................................4 2. System Requirements................................................................4 Handheld ...............................................................................................5 Desktop or Laptop.................................................................................5 Display Device......................................................................................5 3. Visor Installation/Setup.............................................................5 4. PC Creation Software Installation/Setup ..................................6 Installing the Presenter-to-Go PC Creation Software drivers...............6 Un-Installing the PC Creation Software drivers...................................6 5. Creating Your Presentation.......................................................7 Creating Presentations from within Microsoft PowerPoint on your desktop PC (or laptop): .........................................................................7 -

Extraction Report Apple Iphone Logical

Extraction Report Apple iPhone Logical Summary Connection Type Cable No. 210 Extraction start date/time 10/04/2016 1:10:13 PM Extraction end date/time 10/04/2016 1:10:25 PM Extraction Type Logical Extraction ID 70792f86-897d-4288-a86c-f5fff7af0208 Selected Manufacturer Apple Selected Device Name iPhone 5C UFED Physical Analyzer version 4.2.2.95 Version type Time zone settings (UTC) Original UTC value Examiner name Redacted Device Information # Name Value Delete 1 Apple ID Redacted 2 Device Name iPhone 3 Display Name iPhone 4 ICCID 89012300000010049886 5 ICCID 89012300000010049886 6 IMEI 358815053266580 7 Is Encrypted False 8 Last Activation Time 01/01/1970 12:17:42 AM(UTC+0) 9 Last Used ICCID 89012300000010049886 10 Phone Number Redacted 11 Phone Number Redacted 12 Product Name iPhone 5c (A1456/A1532) 13 Product Type iPhone5,3 14 Product Version 8.4.1 15 Serial Number F8RQC1WRFFHH 16 Unique Identifier 2A9AA94D1D07EDF57351CEEA7B9E71C56A63312C Image Hash Details (1) No reference hash information is available for this project. # Name Info 1 FileDump Path iPhoneBackup.tar Size (bytes) 56177279 1 Plugins # Name Author Version 1 iPhone Backup Parser Cellebrite 2.0 Parses all iPhone Backup/Logical/FS dumps, including decryption and/or FileSystem creation when necessary 2 CpioExtractor Cellebrite 2.0 Decode all the CPIO files in the extraction 3 iPhone Databases Logical Cellebrite 2.0 Reads various databases on the iPhone, containing notes, calendar, locations, Safari bookmarks, cookies and history, Facebook friends and bluetooth pairings. 4 iPhone device info Cellebrite 2.0 Decodes device infromation for iPhone devices 5 QuicktimeMetadata Cellebrite 2.0 Extracts metadata from Apple quicktime movies 6 Garbage Cleaner 7 DataFilesHandler Cellebrite 2.0 Tags data files according to extensions and file signatures 8 ContactsCrossReference Cellebrite 2.0 Cross references the phone numbers in a device's contacts with the numbers in SMS messages and Calls. -

Vmware Workspace ONE UEM Ios Device Management

iOS Device Management VMware Workspace ONE UEM iOS Device Management You can find the most up-to-date technical documentation on the VMware website at: https://docs.vmware.com/ VMware, Inc. 3401 Hillview Ave. Palo Alto, CA 94304 www.vmware.com © Copyright 2020 VMware, Inc. All rights reserved. Copyright and trademark information. VMware, Inc. 2 Contents 1 Introduction to Managing iOS Devices 7 iOS Admin Task Prerequisites 8 2 iOS Device Enrollment Overview 9 iOS Device Enrollment Requirements 11 Capabilities Based on Enrollment Type for iOS Devices 11 Enroll an iOS Device Using the Workspace ONE Intelligent Hub 14 Enroll an iOS Device Using the Safari Browser 15 Bulk Enrollment of iOS Devices Using Apple Configurator 16 Device Enrollment with the Apple Business Manager's Device Enrollment Program (DEP) 17 User Enrollment 17 Enroll an iOS Device Using User Enrollment 18 App Management on User Enrolled Devices 19 3 Device Profiles 20 Device Passcode Profiles 22 Configure a Device Passcode Profile 23 Device Restriction Profiles 24 Restriction Profile Configurations 24 Configure a Device Restriction Profile 29 Configure a Wi-Fi Profile 30 Configure a Virtual Private Network (VPN) Profile 31 Configure a Forcepoint Content Filter Profile 33 Configure a Blue Coat Content Filter Profile 34 Configure a VPN On Demand Profile 35 Configure a Per-App VPN Profile 38 Configure Public Apps to Use Per App Profile 39 Configure Internal Apps to Use Per App Profile 39 Configure an Email Account Profile 40 Exchange ActiveSync (EAS) Mail for iOS Devices 41 Configure an EAS Mail Profile for the Native Mail Client 41 Configure a Notifications Profile 43 Configure an LDAP Settings Profile 44 Configure a CalDAV or CardDAV Profile 44 Configure a Subscribed Calendar Profile 45 Configure Web Clips Profile 45 Configure a SCEP/Credentials Profile 46 Configure a Global HTTP Proxy Profile 47 VMware, Inc. -

When Can It Launch a Career? the Real Economic Opportunities of Middle-Skill Work

Building a Future That Works WHEN IS A JOB JUST A JOB —AND WHEN CAN IT LAUNCH A CAREER? THE REAL ECONOMIC OPPORTUNITIES OF MIDDLE-SKILL WORK AT A GLANCE AUTHORS This report studies the career advancement Sara Lamback prospects of people entering middle-skill jobs Associate Director JFF through the unprecedented analysis of nearly 4 million resumes of middle-skill jobseekers. Carol Gerwin Senior Writer/Editor It highlights the types of occupations that JFF offer the strongest opportunities for financial stability and true economic advancement. Dan Restuccia Chief Product and Analytics Officer Burning Glass Technologies JFF is a national nonprofit that drives Lumina Foundation is an independent, transformation in the American workforce private foundation in Indianapolis that is and education systems. For 35 years, JFF has committed to making opportunities for led the way in designing innovative and learning beyond high school available to all. scalable solutions that create access to We envision a system that is easy to navigate, economic advancement for all. Join us as we delivers fair results, and meets the nation’s build a future that works. www.jff.org need for talent through a broad range of credentials. Our goal is to prepare people for informed citizenship and for success in a global economy. www.luminafoundation.org Burning Glass Technologies delivers job market analytics that empower employers, workers, and educators to make data-driven decisions. The company’s artificial intelligence technology analyzes hundreds of millions of job postings and real-life career transitions to provide insight into labor market patterns. This real-time strategic intelligence offers crucial insights, such as which jobs are most in demand, the specific skills employers need, and the career directions that offer the highest potential for workers. -

The Cider Press: Extracting Forensic Artifacts from Apple Continuity Heather Mahalik | @Heathermahalik | Smarterforensics.Com Sarah Edwards | @Iamevltwin | Mac4n6.Com

THE CIDER PRESS: EXTRACTING FORENSIC ARTIFACTS FROM APPLE CONTINUITY HEATHER MAHALIK | @HEATHERMAHALIK | SMARTERFORENSICS.COM SARAH EDWARDS | @IAMEVLTWIN | MAC4N6.COM © 2017 Sarah Edwards and Heather Mahalik WHO THE HECK ARE WE? HEATHER MAHALIK SARAH EDWARDS • SANS SENIOR INSTRUCTOR AND AUTHOR • SANS CERTIFIED INSTRUCTOR AND AUTHOR • DIRECTOR OF FORENSIC ENGINEERING, • MOBILE FORENSICS ENGINEER AT PARSONS MANTECH CARD CORPORATION • SMARTPHONE NERD • MAC NERD © 2017 Sarah Edwards and Heather Mahalik WHAT IS CONTINUITY? • “SEAMLESS” INTERACTION BETWEEN ALL APPLE DEVICES: • MACS • IPHONE • IPAD • APPLE WATCH • SOFTWARE REQUIREMENTS: • WI-FI & BLUETOOTH ON • SIGNED IN ON ALL DEVICES WITH ICLOUD ACCOUNT • “HANDOFF” SET TO ON • HARDWARE REQUIREMENTS: • MACOS 10.10+ (MACBOOK EARLY 2015) • IOS 8+ (IPHONE 5+) • WATCHOS3 - (SERIES 1+) © 2017 Sarah Edwards and Heather Mahalik THE METHOD TO OUR MADNESS • IPHONE 7 IOS 10.3.2 • JAILBROKEN IPHONE 7 IOS 10.1.1 • APPLE WATCH OS 3.1.3 • APPLE WATCH 2 OS 3.1 • MACBOOK PRO X 2 (10.12.3 & 10.12.5) © 2017 Sarah Edwards and Heather Mahalik CONNECTED DEVICES - BLUETOOTH IDENTIFIERS - MAC • /LIBRARY/PREFERENCES/COM.APPLE.BLUETOOTH.PLIST • MATCH GUID -> GET MAC ADDRESS -> ASSOCIATE WITH DEVICE © 2017 Sarah Edwards and Heather Mahalik CONNECTED DEVICES - BLUETOOTH IDENTIFIERS - MAC • ~/LIBRARY/PREFERENCES/BYHOST/COM.APPLE.BLUETOOTH.<HW_UUID>.PLIST • ASSOCIATE WITH A SPECIFIC USER © 2017 Sarah Edwards and Heather Mahalik CONNECTED DEVICES - BLUETOOTH IDENTIFIERS - IOS • /LIBRARY/MOBLEBLUETOOTH/COM.APPLE.MOBILEBLUETOOTH.LEDEVICES.PAIRED.DB -

Welcome to Springboard Digital

Sample Instructional Materials Proclamation 2015 The College Board is pleased to provide access to the Electronic Samples of the 2014©/2015© Texas Edition of SpringBoard Mathematics To access… See Page • Welcome Page……………………………………................................... 2 • Log-in Information……………………………….…………………………….. 3 • Teacher and Student Editions................................................. 4 • TEKS & ELPS Standards............................................................ 5 • Teacher Resources……………………………………………………………… 6 • Assessment with Examview…………………………………………………7 For more information on… • Navigation Tools……………………………………................................ 8 • Interactive Teacher & Student Texts……………………………………. 9 • Hardware Requirements……………………………………………………… 11 SpringBoard Online Mathematics Welcome Page http://texasmath.springboardonline.org Access the Program: Features Guide Correlations: Professional Learning: •Log-in information To both TEKS and •PD Video •Walkthrough ELPS •PD Brochure Texas Edition Page 2 Log-in Information to Mathematics SpringBoard Online For Optimal Viewing Experience, Use Chrome, Safari, or Firefox – or Internet Explorer 9 or above. Experience has not yet been optimized for iPad and other touch devices. 1. Go to http://texasmath.springboardonline.org 2. To Access Both the Teacher Edition and the Student Edition with Annotations, enter your designated code. *To receive your code, please contact your SpringBoard Sales Manager: Travis Goodwin [email protected] 979-739-7232 Dustin Fitzner [email protected] -

An American Journey

UNIT 5 An American Journey Visual Prompt: Duke Ellington (seated at the piano) was a major presence in the Harlem Renaissance. He was famous for playing jazz, although he played other genres as well, such as classical, blues, and gospel. How does the music of an era influence writers? Unit Overview Ever since the Pilgrims traveled to America, the concept of the “journey” has been part of the American experience. In this unit, you will take two journeys. First, you will experience a cultural journey by exploring the voices of the Harlem Renaissance. You will then study one voice in depth by reading Their Eyes Were Watching God, by Zora Neale Hurston. A major writer of the Harlem Renaissance, Hurston will take you on one character’s journey © 2017 College Board. All rights reserved. of self-discovery. G11_U5_SE_B1.indd 395 05/04/16 12:36 pm UNIT An American Journey 5 GOALS: Contents • To explore the concept of “journey” Activities • To analyze a writer’s complex 5.1 Previewing the Unit ................................................................ 398 writing and stylistic choices • To research and synthesize 5.2 Developing Research Questions ..............................................399 information about a Informational Text: “The Harlem Renaissance,” adapted from literary era The 1920s, by Kathleen Drowne and Patrick Huber • To create a multimedia presentation 5.3 The Historical Context of the Harlem Renaissance ..................404 Informational Text: Introduction to The New Negro, by Alain Locke ACADEMIC VOCABULARY Poetry: “To Usward,” by Gwendolyn B. Bennett renaissance Poetry: “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” by James Weldon Johnson annotated bibliography Literary Criticism: Excerpt from “On ‘From the Dark Tower,’” by Eugenia W. -

Springboard® Digital Getting Started Guide

SpringBoard ® Digital Getting Started Guide Contents SpringBoard Digital Getting Started Guide The resources within this manual were developed to assist administrators, instructional leaders, and teachers as they begin a new implementation of SpringBoard® Digital. We recommend that you refer to the following resources as you proceed with implementation and provide ongoing support. You will find the following supports within this manual: SpringBoard Digital Part 1: Overview ................................................................................................................................. 3 Part 2: Getting Started ........................................................................................................................ 4 Part 3: SpringBoard Digital Support ..................................................................................................... 7 Part 4: Accessing SpringBoard Digital .................................................................................................. 8 Part 5: Other Important Information About SpringBoard Digital .............................................................10 Appendix 1.1 SpringBoard Digital Terms and Conditions .....................................................................................13 2 SpringBoard SpringBoard Digital Digital Part 1: Overview The award-winning SpringBoard Digital is in an online version of the entire SpringBoard curriculum, plus a powerful digital platform. SpringBoard Digital makes possible deeper, richer, and more effective -

Hacking Mac OS X

Owning the Fanboys: Hacking Mac OS X Charlie Miller Principal Analyst Independent Security Evaluators [email protected] Who am I? Former National Security Agency (USA) First to hack the iPhone Won MacBook Air at Pwn2Own competition with Safari 0-day Author of “Fuzzing for Software Security Testing and Quality Assurance” Writing “The Mac Hackers Handbook” Due out in January Outline Leopard security Tracing execution Reverse engineering Bug hunting on Macs Exploits Introduction to iPhone Leopard security The good: application sandboxing The bad: Leopard firewall The ugly: library randomization Sandboxing Done via Seatbelt kext Can use default profiles nointernet’, ‘nonet’, ‘nowrite’, ‘write-tmp-only’, and ‘pure-computation’ Or custom written profiles See /usr/share/sandbox for examples Sandboxing demo sandbox-exec -n nonet /bin/bash sandbox-exec –n nowrite /bin/bash More sandboxing Some applications are sandboxed by default: krb5kdc mDNSResponder <--- very good :) mdworker ntpd ... Safari, Mail, QuickTime Player are NOT sandboxed quicklookd.sb (version 1) (allow default) (deny network-outbound) (allow network-outbound (to unix-socket)) (deny network*) (debug deny) Doesn’t allow network connections Imagine malicious file takes over quicklookd - Can’t phone home/ open ports Circumventable: Write a shell script/program to disk Ask launchd (not in sandbox) to execute it via launchctl Leopard firewall Disabled by default Doesn’t block outbound connections No harder to write connect shellcode versus bind shellcode Hard to imagine a scenario -

Exploring the Iphone Backup Made by Itunes

Journal of Digital Forensics, Security and Law Volume 6 Number 3 Article 4 2011 Exploring the iPhone Backup Made by iTunes Mario Piccinelli University of Brescia, Italy Paolo Gubian University of Brescia, Italy Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.erau.edu/jdfsl Part of the Computer Engineering Commons, Computer Law Commons, Electrical and Computer Engineering Commons, Forensic Science and Technology Commons, and the Information Security Commons Recommended Citation Piccinelli, Mario and Gubian, Paolo (2011) "Exploring the iPhone Backup Made by iTunes," Journal of Digital Forensics, Security and Law: Vol. 6 : No. 3 , Article 4. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15394/jdfsl.2011.1099 Available at: https://commons.erau.edu/jdfsl/vol6/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Digital Forensics, Security and Law by an authorized administrator of (c)ADFSL Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Digital Forensics, Security and Law, Vol. 6(3) Exploring the iPhone Backup Made by iTunes Mario Piccinelli PhD candidate in Computer Sciences Department of Information Engineering University of Brescia, Italy [email protected] Paolo Gubian Associate Professor Department of Information Engineering University of Brescia, Italy [email protected] ABSTRACT Apple’s™ iPhone™ is one of the widest selling mobile on the market, thanks to its simple and user-friendly interface and ever growing pool of available high quality applications for both personal and business use. The increasing use of the iPhone leads forensics practitioners towards the need for tools to access and analyze the information stored in the device.