Gathering Kinds: Radical Faerie Practices of Sexuality and Kinship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Barbara Gittings and Kay Tobin Lahusen Collection, 1950-2009 [Bulk: 1964-1975] : Ms.Coll.3](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2283/barbara-gittings-and-kay-tobin-lahusen-collection-1950-2009-bulk-1964-1975-ms-coll-3-92283.webp)

Barbara Gittings and Kay Tobin Lahusen Collection, 1950-2009 [Bulk: 1964-1975] : Ms.Coll.3

Barbara Gittings and Kay Tobin Lahusen collection, 1950-2009 [Bulk: 1964-1975] : Ms.Coll.3 Finding aid prepared by Alina Josan on 2015 PDF produced on July 17, 2019 John J. Wilcox, Jr. LGBT Archives, William Way LGBT Community Center 1315 Spruce Street Philadelphia, PA 19107 [email protected] Barbara Gittings and Kay Tobin Lahusen collection, 1950-2009 [Bulk: 1964-1975] : Ms.Coll.3 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical ................................................................................................................................ 4 Scope and Contents ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 7 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 8 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 8 Subject files ................................................................................................................................................ -

BUTCH ENOUGH? Drummer Presents Some “Found” Prose ©Jack from the Red Queen, Arthur Evans by Jack Fritscher

HOW TO LEGALLY QUOTE THIS MATERIAL www.JackFritscher.com/Drummer/Research%20Note.html DRUMMER EDITORIAL ©Jack Fritscher. See Permissions, Reprints, Quotations, Footnotes GETTING OFF Bitch bites butch, and vice versa... DRAFTBUTCH ENOUGH? Drummer Presents Some “Found” Prose ©Jack from the Red Queen, Arthur Evans by Jack Fritscher This entire editoral "Butch Enough?" is also available in Acrobat pdf. Author's historical introduction Actual editorial as published Illustrations AUTHOR'S HISTORICAL CONTEXT INTRODUCTION Produced September 1978, and publishedFritscher in Drummer 25, December 1978. This piece is about Gay Civil War in the Titanic ’70s. For all its entertainment value, Drummer was a timely test-bed for purposeful versions and visions of the gay-liberation dream unfolding. Some misunderstand homomasculinity as if it were an absolute. When I coined the term in 1972, I meant not masculinity as a power tool of male privilege or male entitlement, but rather a masculinity whose identity was in traditionally masculine goodness in the Latin sense of virtue, which comes from the Latin word vir, meaning man, causing virtue to be the quality of a man, and that was quintessence I sought to define in my coinage. I published this article written by the Red Queen, Arthur Evans, for a reason of political “authenticity” just as I recommend the “authentic” political analysis of unfolding gender ambiguities made by David Van Leer in his benchmark book of the years between World War II and Stonewall, The Queening of America: Gay Culture in a Straight Society. In the gay civil wars of the ’70s, I respected Arthur Evans’ representing one kind of “authentic” queening and queering. -

FWLLC-Sponsors-2008.Pdf

Called “mythically magical... transformational… German bands, Estampie and Qntal (who delivered a one-of-a-kind, otherworldly event,” Faerieworlds show-stopping performances at FaerieCon in 2007!) is the premiere family faerie event on the West Coast, as well as the Faerieworlds premiere of Zilla, lead by featuring international best-selling and award-winning Michael Travis, formerly of String Cheese Incident, plus artists, writers, craftspeople, storytellers, performance Telesma, the psychedelic, electro-acoustic world music artists and world renowned musicians. band from Baltimore, MD and the return of Faerieworlds perennial favorite mythic band, Woodland. Skyrocketing Attendance - Now THREE Days! Faerieworlds achieved an astonishing 98% growth Musicians featured at Faerieworlds events past & present: from 2006 to 2007, with last year’s attendance topping Brother • Kevin Burke • Karan Casey 8000. This year, Faerieworlds expands to three days with over 150 vendor’s booths and an expected Johnny Cunningham • Phil Cunningham attendance of over 10,000. Estampie • Gaia Consort Priscilla Hernandez* • Scott Huckabay Magical Artists: Kan’Nal • Susan McKeown • Casey Neill Jessica Galbreth is Guest of Honor Faerieworlds is proud to welcome internationally Omnia* • Qntal • Rasputina celebrated faerie artist Jessica Galbreth as 2008 Guest John Renbourn • Solas • Telesma* of Honor. Jessica will attend all three days and will be Trillian Green • Wake the Dead available for book and print signings. Woodland • Zilla* *appearing for the first time in -

Test Your Faerie Knowledge

Spiderwick Tes t Your Activity Sheet Faerie Knowledge It wasn’t all that long ago that faeries were regarded as the substance of the imagination. Boggarts, Elves, Dragons, Ogres . mankind scoffed at the idea that such fantastical beings could exist at all, much less inhabit the world around us. Of course, that was before Simon & Schuster published Arthur Spiderwick’s Field Guide to the Fantastical World Around You. Now, we all know that faeries truly do exist. They’re out there, occasionally helping an unwary human, but more often causing mischief and playing tricks. How much do you know about the Invisible World? Have you studied up on your faerie facts? Put your faerie knowledge to the test and see how well you do in the following activities.When you’re finished, total up your score and see how much you really know. SCORING: 1-10 POINTS: Keep studying. In the meantime, you should probably steer clear of faeries of any kind. 11-20 POINTS: Pretty good! You might be able to trick a pixie, but you couldn’t fool a phooka. 21-30 POINTS: Wow, You’re almost ready to tangle with a troll! 31-39 POINTS: Impressive! You seem to know a lot about the faerie world —perhaps you’re a changeling... 40 POINTS: Arthur Spiderwick? Is that you? MY SCORE: REPRODUCIBLE SHEET Page 1 of 4 ILLUSTRATIONS © 2003, 2004, 2005 BY TONY DITERLIZZI Spiderwick Tes t Your Activity Sheet Faerie Knowledge part 1 At any moment, you could stumble across a fantastical creature of the faerie world. -

Chapter Six: Activist Agendas and Visions After Stonewall (1969-1973)

Chapter Six: Activist Agendas and Visions after Stonewall (1969-1973) Documents 103-108: Gay Liberation Manifestos, 1969-1970 The documents reprinted in The Stonewall Riots are “Gay Revolution Comes Out,” Rat, 12 Aug. 1969, 7; North American Conference of Homophile Organizations Committee on Youth, “A Radical Manifesto—The Homophile Movement Must Be Radicalized!” 28 Aug. 1969, reprinted in Stephen Donaldson, “Student Homophile League News,” Gay Power (1.2), c. Sep. 1969, 16, 19-20; Preamble, Gay Activists Alliance Constitution, 21 Dec. 1969, Gay Activists Alliance Records, Box 18, Folder 2, New York Public Library; Carl Wittman, “Refugees from Amerika: A Gay Manifesto,” San Francisco Free Press, 22 Dec. 1969, 3-5; Martha Shelley, “Gay is Good,” Rat, 24 Feb. 1970, 11; Steve Kuromiya, “Come Out, Wherever You Are! Come Out,” Philadelphia Free Press, 27 July 1970, 6-7. For related early sources on gay liberation agendas and philosophies in New York, see “Come Out for Freedom,” Come Out!, 14 Nov. 1969, 1; Bob Fontanella, “Sexuality and the American Male,” Come Out!, 14 Nov. 1969, 15; Lois Hart, “Community Center,” Come Out!, 14 Nov. 1969, 15; Leo Louis Martello, “A Positive Image for the Homosexual,” Come Out!, 14 Nov. 1969, 16; “An Interview with New York City Liberationists,” San Francisco Free Press, 7 Dec. 1969, 5; Bob Martin, “Radicalism and Homosexuality,” Come Out!, 10 Jan. 1970, 4; Allan Warshawsky and Ellen Bedoz, “G.L.F. and the Movement,” Come Out!,” 10 Jan. 1970, 4-5; Red Butterfly, “Red Butterfly,” Come Out!, 10 Jan. 1970, 4-5; Bob Kohler, “Where Have All the Flowers Gone,” Come Out!, 10 Jan. -

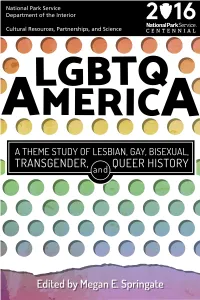

LGBTQ America: a Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History Is a Publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service

Published online 2016 www.nps.gov/subjects/tellingallamericansstories/lgbtqthemestudy.htm LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History is a publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service. We are very grateful for the generous support of the Gill Foundation, which has made this publication possible. The views and conclusions contained in the essays are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. © 2016 National Park Foundation Washington, DC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced without permission from the publishers. Links (URLs) to websites referenced in this document were accurate at the time of publication. PLACES Unlike the Themes section of the theme study, this Places section looks at LGBTQ history and heritage at specific locations across the United States. While a broad LGBTQ American history is presented in the Introduction section, these chapters document the regional, and often quite different, histories across the country. In addition to New York City and San Francisco, often considered the epicenters of LGBTQ experience, the queer histories of Chicago, Miami, and Reno are also presented. QUEEREST28 LITTLE CITY IN THE WORLD: LGBTQ RENO John Jeffrey Auer IV Introduction Researchers of LGBTQ history in the United States have focused predominantly on major cities such as San Francisco and New York City. This focus has led researchers to overlook a rich tradition of LGBTQ communities and individuals in small to mid-sized American cities that date from at least the late nineteenth century and throughout the twentieth century. -

Queer Alchemy: Fabulousness in Gay Male Literature and Film

QUEER ALCHEMY QUEER ALCHEMY: FABULOUSNESS IN GAY MALE LITERATURE AND FILM By ANDREW JOHN BUZNY, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Andrew John Buzny, August 2010 MASTER OF ARTS (2010) McMaster University' (English) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Queer Alchemy: Fabulousness in Gay Male Literature and Film AUTHOR: Andrew John Buzny, B.A. (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Lorraine York NUMBER OF PAGES: v, 124pp. 11 ABSTRACT This thesis prioritizes the role of the Fabulous, an underdeveloped critical concept, in the construction of gay male literature and film. Building on Heather Love's observation that queer communities possess a seemingly magical ability to transform shame into pride - queer alchemy - I argue that gay males have created a genre of fiction that draws on this alchemical power through their uses of the Fabulous: fabulous realism. To highlight the multifarious nature of the Fabulous, I examine Thomas Gustafson's film Were the World Mine, Tomson Highway's novel Kiss ofthe Fur Queen, and Quentin Crisp's memoir The Naked Civil Servant. 111 ACKNO~EDGEMENTS This thesis would not have reached completion without the continuing aid and encouragement of a number of fabulous people. I am extremely thankful to have been blessed with such a rigorous, encouraging, compassionate supervisor, Dr. Lorraine York, who despite my constant erratic behaviour, and disloyalty to my original proposal has remained a strong supporter of this project: THANK YOU! I would also like to thank my first reader, Dr. Sarah Brophy for providing me with multiple opportunities to grow in~ellectually throughout the past year, and during my entire tenure at McMaster University. -

Fairy Gardens.Pub

FairiesandFairyGardens ĐĐŽƌĚŝŶŐƚŽƌŝĂŶ&ƌŽƵĚ͕ ĂƵƚŚŽƌŽĨƚŚĞďĞĂƵƟĨƵůŬ͞ ' ŽŽĚ&ĂĞƌŝĞƐͬ ĂĚ&ĂĞƌŝĞƐ͟ ͗ &ĂĞƌŝĞƐ͞ ĂƌĞůƵŵŝŶŽƵƐ͘ ͘ ͘ ĐƌĞĂƚƵƌĞƐǁ ŚŽĚĂŶĐĞďLJƚŚĞůŝŐŚƚŽĨƚŚĞŵŽŽŶ͕ ďĞĂƵƟĨƵůĂƐƚŚĞ ŵƵƐŝĐŝƚƐĞůĨ͕ ƚƌĂŝůŝŶŐƉĂƩ ĞƌŶƐŽĨĐŽůŽƌĂŶĚŵŝƐƚŝŶƚŚĞŝƌǁ ĂŬĞ͘ &ĂĞƌŝĞƐŽŌĞŶĚĂŶĐĞŝŶĐŝƌͲ ĐůĞƐ͕ ůĞĂǀ ŝŶŐƌŝŶŐƐŽĨŇĂƩ ĞŶĞĚŐƌĂƐƐƚŽŵĂƌŬƚŚĞƐŝƚĞƐŽĨƚŚĞŝƌŵŝĚŶŝŐŚƚƌĞǀ ĞůƐ-- or circles of toadstools springing up where faery feet have trod.” “t ŚĞŶǁ ĞĚĂŶĐĞǁ ŝƚŚƚŚĞĨĂĞƌŝĞƐ͕ ǁ ĞĚĂŶĐĞǁ ŝƚŚƚŚĞƌĞŇĞĐƟŽŶƐŽĨŽƵƌƚƌƵĞƐĞůǀ ĞƐĂŶĚ the true inner self of the world.” They are “ŝƌƌĂƟŽŶĂů͕ ƉŽĞƟĐ͕ ĂďƐƵƌĚ͕ ƉĂƌĂĚŽdžŝĐĂů͕ ĂŶĚǀ ĞƌLJ͕ ǀ ĞƌLJǁ ŝƐĞ͘ They bestow the ŐŝŌƐŽĨŝŶƐƉŝƌĂƟŽŶ͕ ƐĞůĨ-healing, and self-ƚƌĂŶƐĨŽƌŵĂƟŽŶ͘ ͘ ͘ ďƵƚƚŚĞLJĂůƐŽĐƌĞĂƚĞƚŚĞŵŝƐͲ ĐŚŝĞĨŝŶŽƵƌůŝǀ ĞƐ͕ ǁ ŝůĚĚŝƐƌƵƉƟŽŶƐ͕ ƟŵĞƐŽĨŚĂǀ ŽĐ͕ ŵĂĚĂďĂŶĚŽŶ͕ ĂŶĚĚƌĂŵĂƟĐĐŚĂŶŐĞ͘ ͘ ͘ ͘ , ĞŚĂƐ͞ ĂƩ ĞŵƉƚĞĚƚŽĚŝǀ ŝĚĞĨĂĞƌŝĞƐŝŶƚŽŐŽŽĚĂŶĚďĂĚ-- a convenient conceit for us hu- mans, but laughable to the faery folk. Faeries insist on being themselves, shape-ƐŚŝŌŝŶŐ endlessly. Good and bad coexist in some degree in all of Faery's creatures.“ They can be helpful or spiteful if you get on their wrong side: so providing a suitable fairy ƐŝnjĞŐĂƌĚĞŶǁ ŝƚŚĂĨĞǁ ĐŚĂƌŵŝŶŐĂŵĞŶŝƟĞƐŵĂLJďĞLJŽƵƌďĞƐƚǁ ĂLJƚŽƐƚĂLJŽŶƚŚĞŐŽŽĚƐŝĚĞ of these magical, mischievous creatures. A Fairy Garden can be self-contained, or nestled into part of your landscape, remembering the ĨŽůůŽǁ ŝŶŐƟƉƐ͗ ŚŽŽƐĞĂĐŽŶƚĂŝŶĞƌŽƌůŽĐĂƟŽŶ͘ ŶLJŵĂƚĞƌŝĂůĐŽŶƚĂŝŶĞƌŝƐĮ ŶĞ͕ ĂůŽǁ ƐŝĚĞĚŽŶĞǁ ŝůůŐŝǀ ĞLJŽƵĂďĞƩ Ğƌ look. WŝĐŬĂƚŚĞŵĞƚŽŬĞĞƉLJŽƵƌĚŝŽƌĂŵĂĨŽĐƵƐĞĚ͗ ǁ ĂƚĞƌĨĂůů͕ ƉĂƟŽ͕ ĨŽƌĞƐƚ͕ ƉŽŶĚ͕ ŇŽǁ ĞƌŐĂƌĚĞŶ͕ ĞƚĐ͘ Choose a fairy or two that would like to be part of your theme. Place your fairies , mark their spot, then remove them so they will not be in the way as you plant. ŚŽŽƐĞLJŽƵƌƉůĂŶƚƐ͗ ŬĞĞƉŝŶŵŝŶĚƐĐĂůĞ;ƉůĂŶƚƐǁ ŝƚŚƐŵĂůůĞƌůĞĂǀ ĞƐĂŶĚďůŽŽŵƐͿ͕ ůŝŐŚƚĐŽŶĚŝƟŽŶƐ͕ and chose a variety of heights to mimic trees, shrubs, and groundcover. Add a few miniature accessories, or find shells, stones, marbles etc. as a real fairy might to furnish their miniature garden. -

Modern Minoica As Religious Focus in Contemporary Paganism

The artifice of Daidalos: Modern Minoica as religious focus in contemporary Paganism More than a century after its discovery by Sir Arthur Evans, Minoan Crete continues to be envisioned in the popular mind according to the outdated scholarship of the early twentieth century: as a peace-loving, matriarchal, Goddess-worshipping utopia. This is primarily a consequence of more up-to-date archaeological scholarship, which challenges this model of Minoan religion, not being easily accessible to a non-scholarly audience. This paper examines the use of Minoan religion by two modern Pagan groups: the Goddess Movement and the Minoan Brotherhood, both established in the late twentieth century and still active. As a consequence of their reliance upon early twentieth-century scholarship, each group interprets Minoan religion in an idealistic and romantic manner which, while suiting their religious purposes, is historically inaccurate. Beginning with some background to the Goddess Movement, its idiosyncratic version of history, and the position of Minoan Crete within that timeline, the present study will examine the interpretation of Minoan religion by two early twentieth century scholars, Jane Ellen Harrison and the aforementioned Sir Arthur Evans—both of whom directly influenced popular ideas on the Minoans. Next, a brief look at the use of Minoan religious iconography within Dianic Feminist Witchcraft, founded by Zsuzsanna Budapest, will be followed by closer focus on one of the main advocates of modern Goddess worship, thealogian Carol P. Christ, and on the founder of the Minoan Brotherhood, Eddie Buczynski. The use of Minoan religion by the Goddess Movement and the Minoan Brotherhood will be critiqued in the light of Minoan archaeology, leading to the conclusion that although it provides an empowering model upon which to base their own beliefs and practices, the versions of Minoan religion espoused by the Goddess Movement and the Minoan Brotherhood are historically inaccurate and more modern than ancient. -

Airy Faerie Litha 2004

AiryAiry FaerieFaerie Litha, 2004 Publisher’s Notes Publisher’s Notes The Airy Faerie is a publication OK kids lets hear it! Airy Faerie of the Denver Radical Faerie Out of the sheets and into the streets! Tribe. Litha, 2004 2-4-68! For more information you can Being Queer is really Great! contact us at: 3-5-69! Denver Radical Faeries Being fey is just Devine! PO Box 631 Denver, CO 80201-0631 R-U-2-4-1? or send an email to: Being gay is just more fun! [email protected] Yes my lovelies it is that time of the year or visit us at again. PRIDE DAY! That time of year when www.geocities.com/denverfae we take our pride out of mothballs and parade it down Main Street. (Now just a or visit us in person at: quick editor’s note, that is take pride out of The Penn St. Perk mothballs, not take pride in having balls like (13th Ave. at Pennsylvania), a moth…although I guess if that is all you Satyrday Mornings have then you should take pride in them! Be proud of who you are and what Mother About 10ish to around noonish Nature gave you!) ANYWAY! or leave a message at: Welcome to the Litha, 2004 issue of the Airy Faerie. Since Pride Day is right around 720-855-8447 the corner we thought we would stop and take a look at what pride means to us. I would like to put out a few words of Morning Glory thanks to Falcon, who has put together in by Monkey one binder, a copy of all the Airy Faeries, Let them all just fly away Nevermore, no nevermore, we as a tribe, have made. -

Investigating a Contemporay Radical Faerie Manifestation Through

THESIS NAVIGATING CONCIOUSNESS TOWARD LIBERATION: INVESTIGATING A CONTEMPORAY RADICAL FAERIE MANIFESTATION THROUGH A DECOLONIAL LENS Submitted by Kyle Andrew Pape Department of Ethnic Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Summer 2013 Master’s Committee: Advisor: Karina Cespedes Co-Advisor: Roe Bubar Irene Vernon Kathleen Sherman Copyright by Kyle Andrew Pape 2013 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT NAVIGATING CONCIOUSNESS TOWARD LIBERATION: INVESTIGATING A CONTEMPORAY RADICAL FAERIE MANIFESTATION THROUGH A DECOLONIAL LENS This thesis argues for the necessity of decolonial consciousness within queer thought and activism. The historical acts of cultural appropriation enacted by the LGBTQ subculture radical faeries of indigenous peoples are intended for healing. However by investigating contemporary radical faerie culture in Thailand, it is found that colonial culture fundamentally defeats queer liberatory movements from within. Primary data was collected through cyber-ethnographic methods and consists of a photo archive and several online blogs and associated websites. Analyzes emerged through Visual Grounded Theory methodology. This study provides evidence of globalizing colonial discourse and the resulting ineptitude of radical faerie activism. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS During my eight years at Colorado State University I have become intimately involved with the Department of Ethnic Studies and its faculty. It is commonly reiterated among these scholars that “it takes a community” by which we mean nothing can be achieved without each other. To begin I thank Roe Bubar and Karina Cespedes for working with me so closely while providing me room to grow. I thank you both for the commitment you have shown to me and this work, as it surely has been a process of its own. -

The Significant Other: a Literary History of Elves

1616796596 The Significant Other: a Literary History of Elves By Jenni Bergman Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Cardiff School of English, Communication and Philosophy Cardiff University 2011 UMI Number: U516593 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U516593 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not concurrently submitted on candidature for any degree. Signed .(candidate) Date. STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD. (candidate) Date. STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. Signed. (candidate) Date. 3/A W/ STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed (candidate) Date. STATEMENT 4 - BAR ON ACCESS APPROVED I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan after expiry of a bar on accessapproved bv the Graduate Development Committee.