Lauding the Locality: Urban Architecture in Medieval Sienese Painting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uffizi Director Provokes Controversy Over Who Owns Sacred Art? – La Voce Di New York 6/5/20, 9)17 AM

State vs. Church: Uffizi Director Provokes Controversy Over Who Owns Sacred Art? – La Voce di New York 6/5/20, 9)17 AM Sections Close DONATE NOW ! Arts CommentaCondividi!"#$%& State vs. Church: Uffizi Director Provokes Controversy Over Who Owns Sacred Art? Should museums return art that was originally created for churches to their original locations? Italian Hours by Lucy Gordan https://www.lavocedinewyork.com/en/arts/2020/06/04/state-vs-church-uffizi-director-provokes-controversy-over-who-owns-sacred-art/ Page 1 of 13 State vs. Church: Uffizi Director Provokes Controversy Over Who Owns Sacred Art? – La Voce di New York 6/5/20, 9)17 AM Caravaggio's "Four Musicians". Photo: Wikipedia.org Jun 04 2020 “I believe the time has come,” Schmidt said, “for state museums to perform an act of courage and return paintings to the churches for which they were originally created… " . However, this decision is neither popular nor logistically simple for many reasons. For some experts, it's unimaginable. A few days before the official post-Covid-19 reopening of the Uffizi Galleries in Florence on June 2nd, a comment made by its Director, Eike Schmidt, at the ceremony held in the Palazzo Pitti sent shock waves through Italy’s museum community. “I believe the time has come,” he said, “for state museums to perform an act of courage and https://www.lavocedinewyork.com/en/arts/2020/06/04/state-vs-church-uffizi-director-provokes-controversy-over-who-owns-sacred-art/ Page 2 of 13 State vs. Church: Uffizi Director Provokes Controversy Over Who Owns Sacred Art? – La Voce di New York 6/5/20, 9)17 AM return paintings to the churches for which they were originally created… Perhaps the most important example is in the Uffizi: the Rucellai Altarpiece by Duccio di Buoninsegna, which in 1948 was removed from the Basilica of Santa Maria Novella. -

Madonna and Child with Donor

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries Lippo Memmi Sienese, active 1317/1347 Madonna and Child with Donor 1325/1330 tempera on panel painted surface: 50.8 × 23.5 cm (20 × 9 1/4 in.) overall: 51.5 × 24.2 × 0.5 cm (20 1/4 × 9 1/2 × 3/16 in.) framed: 70 x 36.2 x 5.1 cm (27 9/16 x 14 1/4 x 2 in.) Andrew W. Mellon Collection 1937.1.11 ENTRY The painting’s iconography is based on the type of the Hodegetria Virgin. [1] It presents, however, a modernized version of this formula, in keeping with the “humanized” faith and sensibility of the time; instead of presenting her son to the observer as in the Byzantine model, Mary’s right hand touches his breast, thus indicating him as the predestined sacrificial lamb. As if to confirm this destiny, the child draws his mother’s hand towards him with his left hand. The gesture of his other hand, outstretched and grasping the Madonna’s veil, can be interpreted as a further reference to his Passion and death. [2] The painting probably was originally the left wing of a diptych. The half-length Madonna and Child frequently was combined with a representation of the Crucifixion, with or without the kneeling donor. In our panel, the donor, an unidentified prelate, is seen kneeling to the left of the Madonna; his position on the far left of the composition itself suggests that the panel was intended as a pendant to a matching panel to the right. -

The Collaboration of Niccolò Tegliacci and Luca Di Tommè

The Collaboration of Niccolô Tegliacci and Lúea di Tomme This page intentionally left blank J. PAUL GETTY MUSEUM Publication No. 5 THE COLLABORATION OF NICCOLÔ TEGLIACCI AND LUCA DI TOMMÈ BY SHERWOOD A. FEHM, JR. !973 Printed by Anderson, Ritchie & Simon Los Angeles, California THE COLLABORATION OF NICCOLO TEGLIACCI AND LUCA DI TOMMÈ The economic and religious revivals which occurred in various parts of Italy during the late Middle Ages brought with them a surge of .church building and decoration. Unlike the typically collective and frequently anonymous productions of the chan- tiers and ateliers north of the Alps which were often passed over by contemporary chroniclers of the period, artistic creativity in Italy during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries documents the emergence of distinct "schools" and personalities. Nowhere is this phenomenon more apparent than in Tuscany where indi- vidual artists achieved sufficient notoriety to appear in the writ- ings of their contemporaries. For example, Dante refers to the fame of the Florentine artist Giotto, and Petrarch speaks warmly of his Sienese painter friend Simone Martini. Information regarding specific artists is, however, often l^ck- ing or fragmentary. Our principal source for this period, The Lives of the Painters, Sculptors and Architects by Giorgio Vasari, was written more than two hundred years after Giotto's death. It provides something of what is now regarded as established fact often interspersed with folk tales and rumor. In spite of the enormous losses over the centuries, a large num- ber of paintings survived from the Dugento and Trecento. Many of these are from Central Italy, and a relatively small number ac- tually bear the signature of the artist who painted them. -

14Th Century Art in Europe (Proto-Renaissance Period)

Chapter 17: 14th Century Art in Europe (Proto-Renaissance Period) • TERMS: loggia, giornata, sinopia, grisaille, gesso, Book of Hours, predella, ogee arch, corbels, tiercerons, bosses, rosettes Timeline of chapter • Culture: Late Medieval • Style: Proto-Renaissance, 1300-1400 Map 17-1 Europe in the Fourteenth Century. 17-2 Culture: Late Medieval Period/Style: Proto-Renaissance Title: Town Hall and Loggia of the Lancers Medium: Stone and brick Date: 1300-1400 Location: Florence, Italy 17-3 Culture: Late Medieval Period/Style: Proto-Renaissance Artist: Andrea Pisano Title: Doors showing Life of John The Baptist from Baptistery of San Giovanni Medium: Gilded bronze Date: 1300-1400 Location: Florence, Italy 17-4 Culture: Late Medieval Period/Style: Proto-Renaissance Artist: Andrea Pisano Title: Baptism of the Multitude from Doors showing Life of John the Baptist at the Baptistery of San Giovanni Medium: Gilded bronze Date: 1300-1400 Location: Florence, Italy 17-5 Culture: Late Medieval Period/Style: Proto-Renaissance Artist: Cimabue Title: Virgin and Child Enthroned Medium: Tempera and gold on wood panel Date: 1300-1400 ”. 17-6 Culture: Late Medieval Period/Style: Proto-Renaissance Artist: Giotto di Bondone Title: Virgin and Child Enthroned Medium: Tempera and gold on wood panel Date: 1300-1400 17-7 Culture: Late Medieval Period/Style: Proto-Renaissance Artist: Giotto di Bondone Title: Scrovegni (Arena) Chapel Medium: Frescoes Date: 1300-1400 Location: Padua, Italy 17-8 Culture: Late Medieval Period/Style: Proto-Renaissance Artist: Giotto di Bondone Title: Marriage at Cana, Raising of Lazarus, Resurrection, and Lamentation/Noli me Tangere from the Scrovegni (Arena) Chapel Medium: Frescoes Date: 1300-1400 Location: Padua, Italy . -

The Making of an Artist: Activities 1

Page 1 of 11 The Making of an Artist: Activities 1. A Week in a ELEMENTarY Renaissance Workshop In this activity, students research the RESOURCES: practices of a Renaissance workshop Bomford, David, et al. Italian Painting before and write a journal about their own 1400: Art in the Making. London: National “experiences” there. Gallery Publications, 1989. PURPOSE: to prompt students to research Cennini, Cennino d’Andrea. The Craftsman’s the Renaissance workshop—the roles of Handbook: The Italian “Il Libro dell’ Arte.” master, apprentice, and patron and the Translated by David V. Thompson Jr. New types of work performed—and creatively York: Dover, 1960. First published 1933 by translate that information into an account Yale University Press. of day-to-day activities. Cole, Bruce. The Renaissance Artist at Work: PROCEDURE: Have students learn more From Pisano to Titian. New York: Harper and about the practices and organization of the Row, 1983. Renaissance workshop using the resources cited below as a starting point. Have them Thomas, Anabel. The Painter’s Practice in imagine that they are apprenticed in the shop Renaissance Tuscany. Cambridge: Cambridge of an artist they have studied. Ask them to University Press, 1995. write a week’s worth of journal entries that chronicle the activities, personalities, and Wackernagel, Martin. The World of the comings and goings of the master, his family, Florentine Artist: Projects and Patrons, the other shop assistants, and patrons. Entries Workshop and Market. Translated by should also include specific information Alison Luchs. Princeton, NJ: Princeton about the materials and processes used and University Press, 1981. -

Maestà (Madonna and Child with Four Angels) C

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries Master of Città di Castello Italian, active c. 1290 - 1320 Maestà (Madonna and Child with Four Angels) c. 1290 tempera on panel painted surface: 230 × 141.5 cm (90 9/16 × 55 11/16 in.) overall: 240 × 150 × 2.4 cm (94 1/2 × 59 1/16 × 15/16 in.) framed: 252.4 x 159.4 x 13.3 cm (99 3/8 x 62 3/4 x 5 1/4 in.) Samuel H. Kress Collection 1961.9.77 ENTRY This panel, of large dimensions, bears the image of the Maestà represented according to the iconographic tradition of the Hodegetria. [1] This type of Madonna and Child was very popular among lay confraternities in central Italy; perhaps it was one of them that commissioned the painting. [2] The image is distinguished among the paintings of its time by the very peculiar construction of the marble throne, which seems to be formed of a semicircular external structure into which a circular seat is inserted. Similar thrones are sometimes found in Sienese paintings between the last decades of the thirteenth and the first two of the fourteenth century. [3] Much the same dating is suggested by the delicate chrysography of the mantles of the Madonna and Child. [4] Recorded for the first time by the Soprintendenza in Siena c. 1930 as “tavola preduccesca,” [5] the work was examined by Richard Offner in 1937. In his expertise, he classified it as “school of Duccio” and compared it with some roughly contemporary panels of the same stylistic circle. -

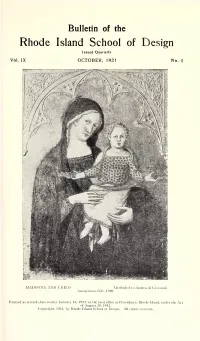

Bulletin of Rhode Island School of Design

Bulletin of the Rhode Island School of Design Issued Quarterly Vol. IX OCTOBER, 1921 No. 4 MADONNA AND CHILD Attributed to Andrea di Giovanni Anonymous Gift, 1920 Entered as second-class matter January 16, 1913, at the post office at Providence, Rhode Island, under the Act of August 24, 1912. Copyright, 1921, by Rhode Island School of Design. All rights reserved. IX, 34 Bulletin of the Rhode Island School of Design MADONNA AND CHILD, he painted in collaboration in 1372, and ATTRIBUTED TO he not infrequently repeated that master’s ANDREA DI GIOVANNI forms, though in a somewhat coarse manner. Pietro da Puccio executed in HE Rhode Island School of Design 1390 the mediocre frescoes of scenes from at Providence has acquired an ex- Genesis on the north wall of the Campo- T santo of ceptionally attractive panel picture Pisa. Of Cola da Petruccioli, of the Madonna and Child, which ap- Mr. Berenson has recently written, iden- pears at first sight to be a product of tifying this modest and not always attrac- 1 the Sienese school of the latter part of tive artist as a follower of Fei. the 14th century. No one will deny the A number of documents exist which en- Sienese character of the picture, although able us to follow the career of Andrea di closer study may suggest its attribution to Giovanni from 1370 to 1417. At the for- Andrea di Giovanni, a painter of Orvieto. mer date he was working with Cola da I recently had occasion to call attention Petruccioli and other painters, under the to the fact that even as late as the begin- direction of Ugolino da Prete Ilario, on the ing of the 15th century painting at Orvieto tribune of the Cathedral of Orvieto; but was dominated by the artistic tradition it is impossible to distinguish in these 1 of Simone Martini. -

The Fathers of Gothic Painting: Cimabue, Duccio, and Giotto

The Fathers of Gothic Painting: Cimabue, Duccio, and Giotto Art Year 2 Lesson 13 The Fathers of Gothic Painting ! Academic Concept: During the Gothic period, the style of art changed resulting in artwork that looked more realistic and natural. Though the change most likely was prompted by cultural shifts, we can see how realism had to be relearned. ! Gospel Principle: Through the Atonement of Jesus Christ we can change. Many of our strengths and faults may be due to our culture, so change requires the gift of discernment. Vocabulary ! Egg Tempera: Ground pigments mixed into a medium of egg yolk and one other ingredient (such as vinegar, white wine, or water). The paint dries very fast and is brittle so it must be on a rigid panel. ! Renaissance Humanism: describes a period of time beginning at the end of the 14th Century, when the cultural focus became less about God and more about classical literature, arts, and people (the subjects commonly referred to as “humanities”). Cimabue, Duccio, Giotto During the Gothic period, the style of art changed resulting in artwork that looked more realistic and natural. Though the change most likely was prompted by cultural shifts, we can see how the skill of realism had to be relearned. Why the Change: Culture or Skill? ! “Renaissance Humanism” (different then “humanism” today), is a term used to describe the cultural shifts that occured at the end of the 14th Century. There was a greater focus on the broader, cultural history of people themselves rather than a sole focus on Diety. ! The beginnings of this shift of emphasis shows up in the paintings of Cimabue, Duccio, and Giotto as they gradually begin to break with Byzantine style and show figures as real people. -

Florence Celebrates the Uffizi the Medici Were Acquisitive, but the Last of the Line Was Generous

ArtNews December 1982 Florence Celebrates The Uffizi The Medici were acquisitive, but the last of the line was generous. She left all the family’s treasures to the people of Florence. by Milton Gendel Whenever I vist The Uffizi Gallery, I start with Raphael’s classic portrait of Leo X and Two Cardinals, in which the artist shows his patron and friend as a princely pontiff at home in his study. The pope’s esthetic interests are indicated by the finely worked silver bell on the red-draped table and an illuminated Bible, which he has been studying with the aid of a gold-mounted lens. The brass ball finial on his chair alludes to the Medici armorial device, for Leo X was Giovanni de’ Medici, the second son of Lorenzo the Magnificent. Clutching the chair, as if affirming the reality of nepotism, is the pope’s cousin, Cardinal Luigi de’ Rossi. On the left is Cardinal Giulio de’ Medici, another cousin, whose look of reverie might be read, I imagine, as foreseeing his own disastrous reign as Pope Clement VII. That was five years in the future, of course, and could not have been anticipated by Raphael, but Leo had also made cardinals of his three nephews, so it wasn’t unlikely that another member of the family would be elected to the papacy. In fact, between 1513 and 1605, four Medici popes reigned in Rome. Leo X was a true Renaissance prince, whose civility and love of the arts impressed everyone - in the tradition of his father, Lorenzo the Magnificent. -

![Madonna and Child with the Blessing Christ, and Saints Peter, James Major, Anthony Abbott, and a Deacon Saint [Entire Triptych] C](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7048/madonna-and-child-with-the-blessing-christ-and-saints-peter-james-major-anthony-abbott-and-a-deacon-saint-entire-triptych-c-1997048.webp)

Madonna and Child with the Blessing Christ, and Saints Peter, James Major, Anthony Abbott, and a Deacon Saint [Entire Triptych] C

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Paintings of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries Martino di Bartolomeo Sienese, active 1393/1434 Madonna and Child with the Blessing Christ, and Saints Peter, James Major, Anthony Abbott, and a Deacon Saint [entire triptych] c. 1415/1420 tempera on panel Inscription: middle panel, on Christ's book: Ego S / um lu / x m / undi / [et] via / veritas / et vita / quise / gui ... (I am the light of the world and the way, the truth and the life; a conflation of John 8:12 and 14:6) [1] Gift of Samuel L. Fuller 1950.11.1.a-c ENTRY This triptych's image of the Madonna and Child recalls the type of the Glykophilousa Virgin, the “affectionate Madonna.” She rests her cheek against that of the child, who embraces her. The motif of the child’s hand grasping the hem of the neckline of the Virgin’s dress seems, on the other hand, to allude to the theme of suckling. [1] The saints portrayed are easily identifiable by their attributes: Peter by the keys, as well as by his particular facial type; James Major, by his pilgrim’s staff; Anthony Abbot, by his hospitaller habit and T-shaped staff. [2] But the identity of the deacon martyr saint remains uncertain; he is usually identified as Saint Stephen, though without good reason, as he lacks that saint’s usual attributes. Perhaps the artist did not characterize him with a specific attribute because the triptych was destined for a church dedicated to him. -

Duccio Di Buoninsegna (About 1255 – 1318)

Duccio di Buoninsegna Duccio di Buoninsegna (about 1255 – 1318) Clues: 1. Montepulciano 2. Founder of Siennese School of Painting 3. Egg Tempera 4. Painted Religious Subjects with Sensitivity and Expression 5. Painted High Altarpiece in Sienna 6. $45,000,000 USD Paid For Painting The language of Byzantine medieval art was a rigid system of icons and symbols. It would require an artist with a rebellious streak to begin to break the chains of such extreme conformity. Duccio di Buoninsegna was just such a man, and earned at least nine fines from the authorities for his frequent unruly behavior. Museum Tour We will be taking a virtual tour of Duccio di Buoninsegna’s most famous works. When you are connected to the Internet, click on the buttons and you will be brought to websites where you can find additional images and information on the artist. To get the greatest benefit of this tour, take a sketchpad in hand and draw from Duccio’s paintings, also taking notes of any thoughts or impressions that you may have. If drawing is not something you are comfortable with, just enjoy the pictures, absorbing the colors, forms and design. Copyright to all intellectual property, articles, images, text, projects, lessons and exercises within 1 this document belong to Diane Cardaci and may not be reproduced or used for any commercial purposes whatsoever without the written permission of Diane Cardaci. Website: www.dianecardaci.com E‐mail: [email protected] Duccio di Buoninsegna Racellai Madonna (about 1285) When we study the work of masters from a faraway era it is important to view them through the prism of their time. -

Early Renaissance Italian Art

Dr. Max Grossman ARTH 3315 Fox Fine Arts A460 Spring 2019 Office hours: T 9:00-10:15am, Th 12:00-1:15pm CRN# 22554 Office tel: 915-747-7966 T/Th 3:00-4:20pm [email protected] Fox Fine Arts A458 Early Renaissance Italian Art The two centuries between the birth of Dante Alighieri in 1265 and the death of Cosimo de’ Medici in 1464 witnessed one of the greatest artistic revolutions in the history of Western civilization. The unprecedented economic expansion in major Italian cities and concomitant spread of humanistic culture and philosophy gave rise to what has come to be called the Renaissance, a complex and multifaceted movement embracing a wide range of intellectual developments. This course will treat the artistic production of the Italian city-republics in the late Duecento, Trecento and early Quattrocento, with particular emphasis on panel and fresco painting in Siena, Florence, Rome and Venice. The Early Italian Renaissance will be considered within its historical, political and social context, beginning with the careers of Duccio di Buoninsegna and Giotto di Bondone, progressing through the generation of Gentile da Fabriano, Filippo Brunelleschi and Masaccio, and concluding with the era of Leon Battista Alberti and Piero della Francesca. INSTRUCTOR BIOGRAPHY Dr. Grossman earned his B.A. in Art History and English at the University of California- Berkeley, and his M.A., M.Phil. and Ph.D. in Art History at Columbia University. After seven years of residence in Tuscany, he completed his dissertation on the civic architecture, urbanism and iconography of the Sienese Republic in the Middle Ages and Early Renaissance.