1 Submission to the 94Th Session of the UN Committee on The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

19 Language Revitalisation: Community and School Programs Working Together

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sydney eScholarship 19 Language revitalisation: community and school programs working together Diane McNaboe1 and Susan Poetsch2 Abstract Since it was published in 2003 the New South Wales Aboriginal Languages K– 10 Syllabus has led to a substantial increase in the number of school programs operating in the state. It has supported the quality of those programs, and the status and recognition given to Aboriginal languages and cultures in the curriculum. School programs also complement community initiatives to revitalise, strengthen and share Aboriginal languages in New South Wales. As linguistic and cultural knowledge increases among adult community members, school programs provide a channel for them to continue to develop their own skills and knowledge and to pass on this heritage. This paper takes Wiradjuri as an example of language revitalisation, and describes achievements in adult language learning and the process of developing a school program with strong input from community. A brief history of Wiradjuri language revitalisation Wiradjuri is one of the central inland New South Wales (NSW) languages (Wafer & Lissarrague 2008, pp. 215–25). In recent decades various language teams have investigated and analysed archival sources for Wiradjuri and collected information from both written and oral sources (Büchli 2006, pp. 58–60). These teams include Grant and Rudder (2001a, b, c, d; 2005), Hosking and McNicol (1993), McNicol and Hosking (1994) and Donaldson (1984), as well as Christopher Kirkbright, George Fisher and Cheryl Riley, who have been working with Wiradjuri people in and near Sydney. -

NUCLEAR POWER: MIRACLE OR MELTDOWN Jim Green

URANIUM MINING This PowerPoint is posted at www. tiny.cc /c1xwb URANIUM weighing benefits and problems BENEFITS Jobs Export revenue Climate change? PROBLEMS Environmental impacts ‘Radioactive racism’CLIMATE CHANGE? Nuclear weapons proliferation Nuclear power risks e.g. reactor accidents, attacks on nuclear plants JOBS 1750 = <0.02% of all jobs in Australia EXPORT REVENUE $751 million in 2009 -10 Uranium accounts for about one-third of one percent of Australian export revenue … 0.38% in 2007 0.36% in 2008/09 Approx. 0.25% in 2009/10 CLIMATE CHANGE BENEFITS OF URANIUM AND NUCLEAR POWER? Greenhouse emissions intensity (Grams CO2-e / kWh) Coal 1200 Nuclear 66 Wind 22 Does Australian uranium reduce global greenhouse emissions? The answer depends on whether Australian uranium displaces i) alternative uranium sources ii) more greenhouse-intensive energy sources (e.g. coal) iii) less greenhouse-intensive energy sources (e.g. wind power) CLIMATE CHANGE BENEFITS OF URANIUM AND NUCLEAR POWER? OLYMPIC DAM MINE Greenhouse emissions projected to increase to 5.9 million tonnes annually. This will make it impossible for South Australia to reach its legislated emissions target of 13 million tonnes annually by 2050. URANIUM weighing benefits and problems BENEFITS Jobs <0.02% Export revenue $ ~0.33% Climate change? benefits compared to fossil fuels but not renewables PROBLEMS Environmental impacts Nuclear weapons proliferation risks ‘Radioactive racism’ Nuclear power risks e.g. reactor accidents, attacks on nuclear plants Olympic Dam mine fire, 2001 Radioactive tailings, Olympic Dam Radioactive tailings, Olympic Dam Leaking tailings dam, Olympic Dam, 2008 BHP Billiton threatened “disciplinary action” against any workers caught taking photos of the mine site. -

Re-Awakening Languages: Theory and Practice in the Revitalisation Of

RE-AWAKENING LANGUAGES Theory and practice in the revitalisation of Australia’s Indigenous languages Edited by John Hobson, Kevin Lowe, Susan Poetsch and Michael Walsh Copyright Published 2010 by Sydney University Press SYDNEY UNIVERSITY PRESS University of Sydney Library sydney.edu.au/sup © John Hobson, Kevin Lowe, Susan Poetsch & Michael Walsh 2010 © Individual contributors 2010 © Sydney University Press 2010 Reproduction and Communication for other purposes Except as permitted under the Act, no part of this edition may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or communicated in any form or by any means without prior written permission. All requests for reproduction or communication should be made to Sydney University Press at the address below: Sydney University Press Fisher Library F03 University of Sydney NSW 2006 AUSTRALIA Email: [email protected] Readers are advised that protocols can exist in Indigenous Australian communities against speaking names and displaying images of the deceased. Please check with local Indigenous Elders before using this publication in their communities. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Re-awakening languages: theory and practice in the revitalisation of Australia’s Indigenous languages / edited by John Hobson … [et al.] ISBN: 9781920899554 (pbk.) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Aboriginal Australians--Languages--Revival. Australian languages--Social aspects. Language obsolescence--Australia. Language revival--Australia. iv Copyright Language planning--Australia. Other Authors/Contributors: Hobson, John Robert, 1958- Lowe, Kevin Connolly, 1952- Poetsch, Susan Patricia, 1966- Walsh, Michael James, 1948- Dewey Number: 499.15 Cover image: ‘Wiradjuri Water Symbols 1’, drawing by Lynette Riley. Water symbols represent a foundation requirement for all to be sustainable in their environment. -

EORA Mapping Aboriginal Sydney 1770–1850 Exhibition Guide

Sponsored by It is customary for some Indigenous communities not to mention names or reproduce images associated with the recently deceased. Members of these communities are respectfully advised that a number of people mentioned in writing or depicted in images in the following pages have passed away. Users are warned that there may be words and descriptions that might be culturally sensitive and not normally used in certain public or community contexts. In some circumstances, terms and annotations of the period in which a text was written may be considered Many treasures from the State Library’s inappropriate today. Indigenous collections are now online for the first time at <www.atmitchell.com>. A note on the text The spelling of Aboriginal words in historical Made possible through a partnership with documents is inconsistent, depending on how they were heard, interpreted and recorded by Europeans. Original spelling has been retained in quoted texts, while names and placenames have been standardised, based on the most common contemporary usage. State Library of New South Wales Macquarie Street Sydney NSW 2000 Telephone (02) 9273 1414 Facsimile (02) 9273 1255 TTY (02) 9273 1541 Email [email protected] www.sl.nsw.gov.au www.atmitchell.com Exhibition opening hours: 9 am to 5 pm weekdays, 11 am to 5 pm weekends Eora: Mapping Aboriginal Sydney 1770–1850 was presented at the State Library of New South Wales from 5 June to 13 August 2006. Curators: Keith Vincent Smith, Anthony (Ace) Bourke and, in the conceptual stages, by the late Michael -

Yarnupings Issue 1 March 2018

March 2018 Issue 2 Aboriginal Heritage Office Yarnupings www.aboriginalheritage.org In this Edition: ∗ NSW Aboriginal Knockout in Dubbo 2018 ∗ It’s a Funny World ∗ Is it possible? ∗ Kids page... Nature Page ∗ Crossword & Quizerama ∗ Book Review: A Fortunate Life by A.B Facey ∗ This Months Recipe : Chicken Pot Roast ∗ Strathfield Sites ∗ YarnUp Review: Guest Speaker Tjimpuna ∗ Walk of the Month: West Head Loop Mackerel Beach -West Head Loop Shell Fish -Hooks Page 2 For at least the last thousand years BC (Before Cook) the waters of Warringá (Middle Har- bour), Kay -ye -my (North Harbour), Weé -rong (Sydney Cove) and other Sydney estuaries were the scenes of people using shell fish -hooks to catch a feed. With no known surviving oral tradition for how and who would make the fish -hooks and use them in this area, the historical and archaeological records become more important. What do we know? Shell fish -hooks were observed and reported on by a number of people from the First Fleet. They mention being made and used by local women. “Considering the quickness with which they are finished, the excellence of the work, if it be inspected, is admirable”, Watkin Tench said on witnessing Barangaroo making one on the north shore. First Fleet painting of fish -hook (T. Watling) The manufacturing process involved the use of a strong shell. So far the only archaeological evidence is from the Turbo species. Pointed stone files were used to create the shape and then file down the edges to the recognisable form. Use -wear analysis on files has confirmed that they were used on shell as well as wood, bone and plant material. -

FPA Legislation Committee Tabled Docu~Ent No. \

FPA Legislation Committee Tabled Docu~ent No. \, By: Mr~ C'-tn~:S AOlSC, Date: b IV\a,c<J..-. J,od.D , e,. t\-40.M I ---------- - ~ -- Australian Government National IndigeJrums Australlfans Agency OFFICIAL Chief Executive Officer Ray Griggs AO, CSC Reference: EC20~000257 Senator Tim Ayres Labor Senator for New South Wales Deputy Chair, Senate Finance and Public Administration Committee 6 March 2020 Re: Additional Estimates 2019-2020 Dear Senatafyres ~l Thank you for your letter dated 25 February 2020 requesting information about Indigenous Advancement Strategy (IAS) and Aboriginals Benefit Account (ABA) grants and unsuccessful applications for the periods 1 January- 30 June 2019 and 1 July 2019 (Agency establishment) - 25 February 2020. The National Indigenous Australians Agency has prepared the attached information; due to reporting cycles, we have provided the requested information for the period 1 January 2019 - 31 January 2020. However we can provide the information for the additional period if required. As requested, assessment scores are provided for the merit-based grant rounds: NAIDOC and ABA. Assessment scores for NAIDOC and ABA are not comparable, as NAIDOC is scored out of 20 and ABA is scored out of 15. Please note as there were no NAIDOC or ABA grants/ unsuccessful applications between 1 July 2019 and 31 January 2020, Attachments Band D do not include assessment scores. Please also note the physical location of unsuccessful applicants has been included, while the service delivery locations is provided for funded grants. In relation to ABA grants, we have included the then Department's recommendations to the Minister, as requested. -

Traditional Wiradjuri Culture

Traditional Wiradjuri Culture By Paul greenwood I would like to acknowledge the Wiradjuir Elders, past and present, and thank those who have assisted with the writing of this book. A basic resource for schools made possible by the assistance of many people. Though the book is intended to provide information on Wiradjuri culture much of the information is generic to Aboriginal culture. Some sections may contain information or pictures from outside the Wiradjuri Nation. Traditional Wiradjuri Culture Wiradjuri Country There were many thousands of people who spoke the Wiradjuri language, making it the largest nation in NSW. The Wiradjuri people occupied a large part of central NSW. The southern border was the Murray River from Albury upstream towards Tumbarumba area. From here the border went north along the edges of the mountains, past Tumut and Gundagai to Lithgow. The territory continued up to Dubbo, then west across the plains to the Willandra creek near Mossgiel. The Booligal swamps are near the western border and down to Hay. From Hay the territory extended across the Riverina plains passing the Jerilderie area to Albury. Wiradjuri lands were known as the land of three rivers; Murrumbidgee (Known by its traditional Wiradjuri name) Gulari (Lachlan) Womboy (Macquarie) Note: The Murrumbidgee is the only river to still be known as its Aboriginal name The exact border is not known and some of the territories overlapped with neighbouring groups. Places like Lake Urana were probably a shared resource as was the Murray River. The territory covers hills in the east, river floodplains, grasslands and mallee country in the west. -

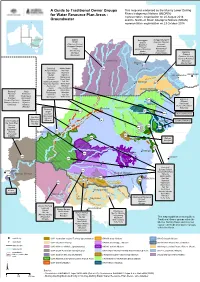

A Guide to Traditional Owner Groups For

A Guide to Traditional Owner Groups Th is m ap w as e nd orse d by th e Murray Low e r Darling Rive rs Ind ige nous Nations (MLDRIN) for Water Resource Plan Areas - re pre se ntative organisation on 20 August 2018 Groundwater and th e North e rn Basin Aboriginal Nations (NBAN) re pre se ntative organisation on 23 Octobe r 2018 Bidjara Barunggam Gunggari/Kungarri Budjiti Bidjara Guwamu (Kooma) Guwamu (Kooma) Bigambul Jarowair Gunggari/Kungarri Euahlayi Kambuwal Kunja Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Mandandanji Mandandanji Murrawarri Giabel Bigambul Mardigan Githabul Wakka Wakka Murrawarri Githabul Guwamu (Kooma) M Gomeroi/Kamilaroi a r a Kambuwal !(Charleville n o Ro!(ma Mandandanji a GW21 R i «¬ v Barkandji Mutthi Mutthi GW22 e ne R r i i «¬ am ver Barapa Barapa Nari Nari d on Bigambul Ngarabal C BRISBANE Budjiti Ngemba k r e Toowoomba )" e !( Euahlayi Ngiyampaa e v r er i ie Riv C oon Githabul Nyeri Nyeri R M e o r Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Tati Tati n o e i St George r !( v b GW19 i Guwamu (Kooma) Wadi Wadi a e P R «¬ Kambuwal Wailwan N o Wemba Wemba g Kunja e r r e !( Kwiambul Weki Weki r iv Goondiwindi a R Barkandji Kunja e GW18 Maljangapa Wiradjuri W n r on ¬ Bigambul e « Kwiambul l Maraura Yita Yita v a r i B ve Budjiti Maljangapa R i Murrawarri Yorta Yorta a R Euahlayi o n M Murrawarri g a a l rr GW15 c Bigambul Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Ngarabal u a int C N «¬!( yre Githabul R Guwamu (Kooma) Ngemba iv er Kambuwal Kambuwal Wailwan N MoreeG am w Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Wiradjuri o yd Barwon River i R ir R Kwiambul !(Bourke iv iv Barkandji e er GW13 C r GW14 Budjiti -

North West Wiradjuri Language and Culture Nest Stage 1 Final Report

North West Wiradjuri Language and Culture Nest Stage 1 Final Report Prepared for participating Aboriginal Communities and members of the North West Wiradjuri Language and Culture Nest Reference Group June 2018 Ilan Katz, Jan Idle, Shona Bates, Wendy Jopson, Michael Barnes This report belongs to the Aboriginal Communities of Dubbo, Narromine, Gilgandra, Peak Hill, Trangie, Wellington and Mudgee, and the North West Wiradjuri Language and Culture Nest Reference Group. The North West Wiradjuri Language and Culture Nest operates on Wiradjuri Country. The evaluation team from the Social Policy Research Centre acknowledges the Wiradjuri peoples as the traditional custodians of the land we work on and pay our respect to Elders past, present and future and all Aboriginal peoples in the region. Acknowledgements We thank Aboriginal Communities involved for their support and participation in this evaluation. We would like to thank Tony Dreise and Dr Lynette Riley – both members of the Evaluation Steering Committee – for reviewing the report. The OCHRE Evaluation was funded by Aboriginal Affairs NSW. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and may not reflect those of Aboriginal Affairs NSW or the New South Wales Government. We would like to acknowledge the contribution of Aboriginal Affairs NSW for their support. Evaluation Team Prof Ilan Katz, Michael Barnes, Shona Bates, Dr Jan Idle, Wendy Jopson, Dr BJ Newton For further information: Ilan Katz +61 2 9385 7800 Social Policy Research Centre UNSW Sydney NSW 2052 Australia T +61 2 9385 7800 F +61 2 9385 7838 E [email protected] W www.sprc.unsw.edu.au © UNSW Australia 2018 The Social Policy Research Centre is based in the Faculty of Arts & Social Sciences at UNSW Sydney. -

Rare Books Lib

RBTH 2239 RARE BOOKS LIB. S The University of Sydney Copyright and use of this thesis This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copynght Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act gran~s the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author's moral rights if you: • fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work • attribute this thesis to another author • subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author's reputation For further information contact the University's Director of Copyright Services Telephone: 02 9351 2991 e-mail: [email protected] Camels, Ships and Trains: Translation Across the 'Indian Archipelago,' 1860- 1930 Samia Khatun A thesis submitted in fuUUment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History, University of Sydney March 2012 I Abstract In this thesis I pose the questions: What if historians of the Australian region began to read materials that are not in English? What places become visible beyond the territorial definitions of British settler colony and 'White Australia'? What past geographies could we reconstruct through historical prose? From the 1860s there emerged a circuit of camels, ships and trains connecting Australian deserts to the Indian Ocean world and British Indian ports. -

PRG 1686 Series List Page 1 of 4 Sister Michele Madiga

_________________________________________________________________________ Sister Michele Madigan PRG 1686 Series List _________________________________________________________________________ Subject files relating to the campaign against the proposed radioactive 1 dump in South Australia. 1998-2004. 21.5 cm. Comprises subject files compiled by Michele Madigan: File 1: Environmentalists’ information and handouts File 2: Environmentalists’ information and handouts File 3: Greenpeace submission re radioactive wastes disposal File 4: Kupa Piti Kungka Tjuta (Coober Pedy Senior Aboriginal Women’s Council) campaign against radioactive dump papers File 5: Kupa Piti Kungka Tjuta – press clippings File 6: Coober Pedy town group campaign against a radioactive dump File 7: Postcards and printed material File 8: Michele Madigan’s personal correspondence against a radioactive dump File 9: SA Parliamentary proceedings against a radioactive dump File 10: Federal Government for a radioactive dump. File 11: Press cuttings. File 12: Brochures, blank petition forms and information, produced by various groups (Australian Conservation Foundation, Friends of the Earth, etc. Subject files relating to uranium mining (mainly in S.A.) 2 1996-2011. 10 cm. Comprises seven files which includes brochures, press clippings, emails, reports and newsletters. File 1 : Roxby Downs – Western Mining (WMC) / Olympic Dam File 2: Ardbunna elder, Kevin Buzzacott. File 3: Beverley and Honeymoon mines in South Australia. File 4: Background to uranium mining in Australia. File 5: Proposed expansion of Olympic Dam. File 6: Transportation of radioactive waste including across South Australia. File 7: Northern Territory traditional owners against Mukaty Dump proposal. PRG 1686 Series list Page 1 of 4 _________________________________________________________________________ Subject files relating to the British nuclear explosions at Maralinga 3 in the 1950s and 1960s. -

Indigenous Knowledge in the Built Environment a Guide for Tertiary Educators

Indigenous Knowledge in The Built Environment A Guide for Tertiary Educators David S Jones, Darryl Low Choy, Richard Tucker, Scott Heyes, Grant Revell & Susan Bird Support for the production of this publication has been 2018 provided by the Australian Government Department of Education and Training. The views expressed in this report do ISBN not necessarily reflect the views of the Australian Government 978-1-76051-164-7 [PRINT], Department of Education and Training. 978-1-76051-165-4 [PDF], With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and 978-1-76051-166-1 [DOCX] where otherwise noted, all material presented in this document is provided under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 Citation: International License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Jones, DS, D Low Choy, R Tucker, SA Heyes, G Revell & S Bird by-sa/4.0/ (2018), Indigenous Knowledge in the Built Environment: A Guide The details of the relevant licence conditions are available on for Tertiary Educators. Canberra, ACT: Australian Government the Creative Commons website (accessible using the links Department of Education and Training. provided) as is the full legal code for the Creative Commons Attribution- ShareAlike 4.0 International License http:// Warning: creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/legalcode Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are warned that the following document may contain images and names of Requests and inquiries concerning these rights should be deceased persons. addressed to: Office for Learning and Teaching A Note on the Project’s Peer Review Process: Department of Education The content of this teaching guide has been independently GPO Box 9880, peer reviewed by five Australian academics that specialise Location code N255EL10 in the teaching of Indigenous knowledge systems within the Sydney NSW 2001 built environment professions, two of which are Aboriginal [email protected] academics and practitioners.